CHAPTER FIVE

The River’s First Bridge

FROM our point of view, engaged as we are in the study of London’s River and its influence on the city, perhaps the most interesting thing that happened in Norman days was the building of the first stone London Bridge.

Other bridges there had been from remote times, and these had taken their part in the moulding of the history of London, but they had suffered seriously from flood, fire, and warfare. In the year 1090, for instance, a tremendous storm had burst on the city, and while the wind blew down six hundred houses and several churches, the flood had entirely demolished the bridge. The citizens had built another in its place; but that, too, had narrowly escaped destruction when there occurred one of those dreadful fires which FitzStephen laments. The years 1135-6 again had brought calamity, for yet another fire had practically consumed the entire structure. It had been remade, however, and had lasted till 1163, when it had been found to be in such a very bad condition that an entirely new bridge was a necessity.

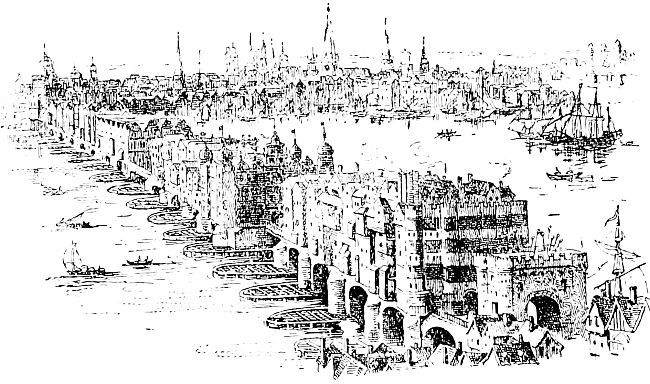

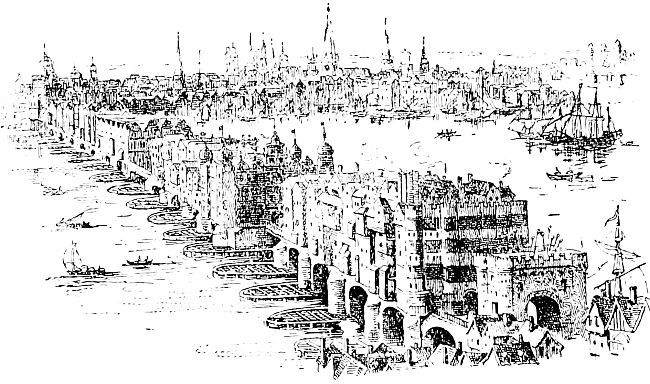

OLD LONDON BRIDGE.

The new bridge was the conception of one Peter, the priest of a small church, St. Mary Colechurch, in the Poultry. This clergyman was a member of a religious body whose special interest was the building of bridges, in those times regarded as an act of piety. Skilled in this particular craft, he dreamed of a bridge for London such as his brother craftsmen were building in the great cities of France; and he set to work to amass the necessary funds. King, courtiers, common folk, all responded to his call, and at last, in 1176, he was able to commence. Unfortunately, he died before the completion of his project, for it took thirty-three years to build; and another brother, Isenbert, carried on after him.

A strange bridge it was, too, when finished; but good enough to last six and a half centuries. It was in reality a street built across the River, 926 feet in length, 40 feet wide, and some 60 feet above the level of high water. Nineteen pointed arches, varying in width from 10 to 32 feet, upheld its weight over massive piers which measured from 23 to 36 feet in thickness. So massive were these piers that probably only about a third of the whole length of the Bridge was waterway. This, of course, meant that the practice of “shooting” the arches in a boat was a perilous adventure, for with such narrow openings the current was tremendous. So dangerous was it that it was usual for timid folk to disembark just above the Bridge, walk round the end, and re-embark below, rather than [150]

[151]take the risk of being dashed against the stone-work. Which wisdom was embodied in a proverb of the time—“London Bridge was made for wise men to go over and fools to go under.”

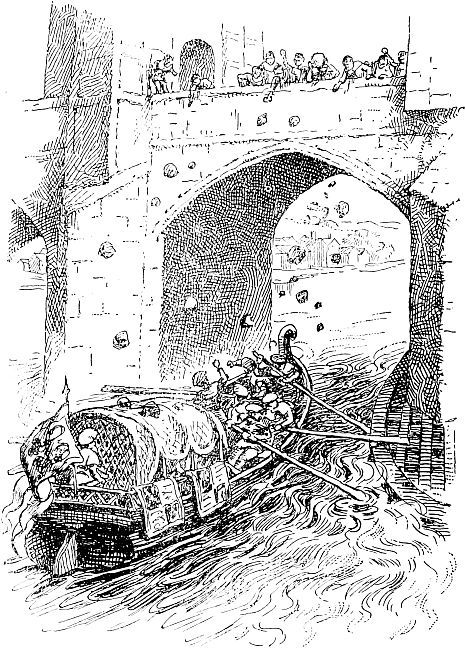

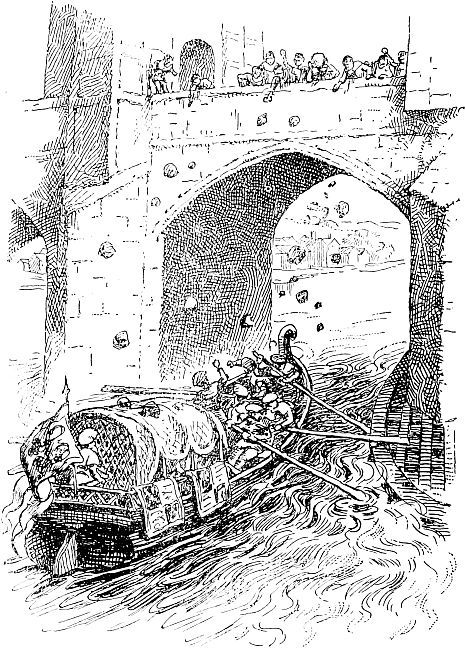

AN ARCH OF OLD LONDON BRIDGE: QUEEN ELEANOR BEING STONED IN 1263.

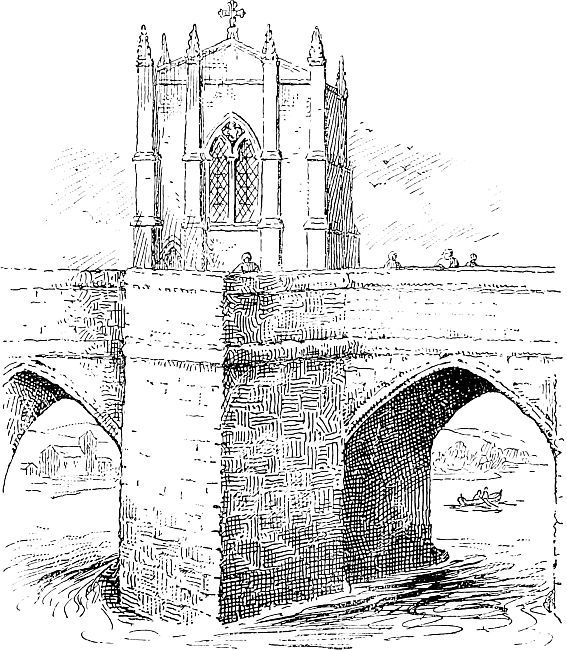

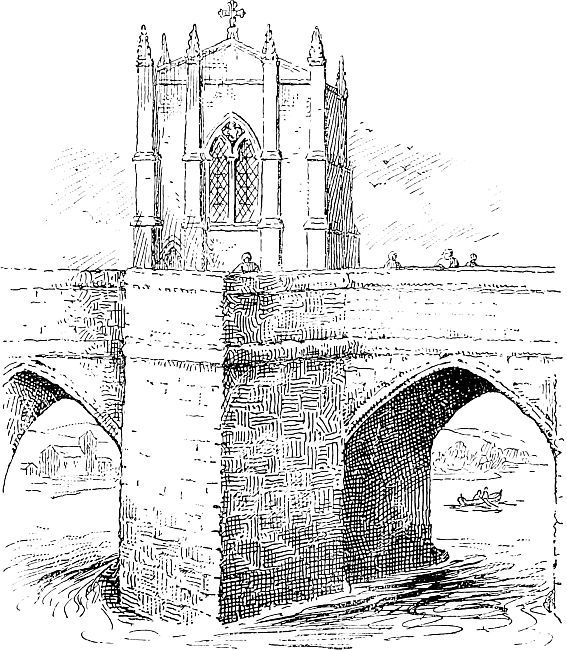

Strangely enough, old London Bridge forestalled the Tower Bridge by having in its centre a drawbridge, which could be raised to allow vessels to sail through, much as the bascules of the modern bridge can be lifted to allow the passage of the great ships of to-day. There were on each side of the roadway ordinary houses, the upper stories of which were used for dwellings, while the ground floors acted as shops. In the middle of the Bridge, over the tenth and largest pier, stood a small chapel dedicated to St. Thomas of Canterbury, the youngest of England’s saints.

But, even when a stone bridge was erected, troubles were by no means over. Four years after the completion, in July, 1212, came another disastrous fire, and practically all the houses, which, unlike the Bridge itself, were built of timber, were destroyed. In the year 1282 it was the turn of the River to play havoc. As we said just now, only about a third of the length was waterway. This condition of things (avoided in all modern bridges) meant a tremendous pressure of the current, both at ebb and flow, and an enormous pressure at flood time. When, in the year mentioned, there came great ice-floods, five arches were carried away, and “London Bridge was broken down, my fair lady.” From that time onwards there was a considerable series of accidents right down to the time of the Great Fire of London, concerning which we shall read in a later chapter.

CHAPEL OF ST. THOMAS BECKET.

Old London Bridge, during its life, saw many strange happenings. In 1263, for instance, a great crowd gathered, wherever the citizens could find a coign of vantage, for the Queen, Eleanor of Provence and wife of Henry III., was passing that way on her journey from the Tower to Windsor. But this was no triumphal passage, for the Queen was strongly opposed to the Barons, who were still working for a final settlement of Magna Charta. Enraged at her action, the people of London waited till her barge approached the Bridge, and then they hurled heavy stones down upon it and assailed the Queen with rough words; so that she was compelled with her attendants to return to the Tower, rather than face the enraged mob.

The year 1390 saw yet another queer event. Probably most of you understand what is meant by a tournament. Well, at this time, there was much rivalry between the English and Scottish knights, and a tilt was proposed between two champions, Lord Wells of England and Earl Lindsay of Scotland. The Englishman, granted choice of ground, chose by some strange whim London Bridge for the scene of action rather than some well-known tournament ground. On the appointed day the Bridge was thronged with folk who had come to witness this unusual contest in the narrow street. Great was the excitement as the knights charged towards each other. Three times did they meet in the shock of battle, and at the third the Englishman fell vanquished from his charger, to be attended immediately by the gallant Scottish knight.

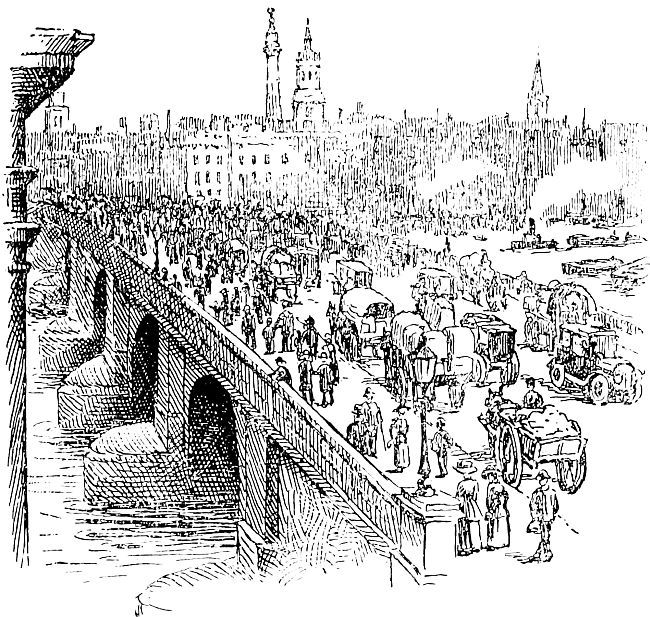

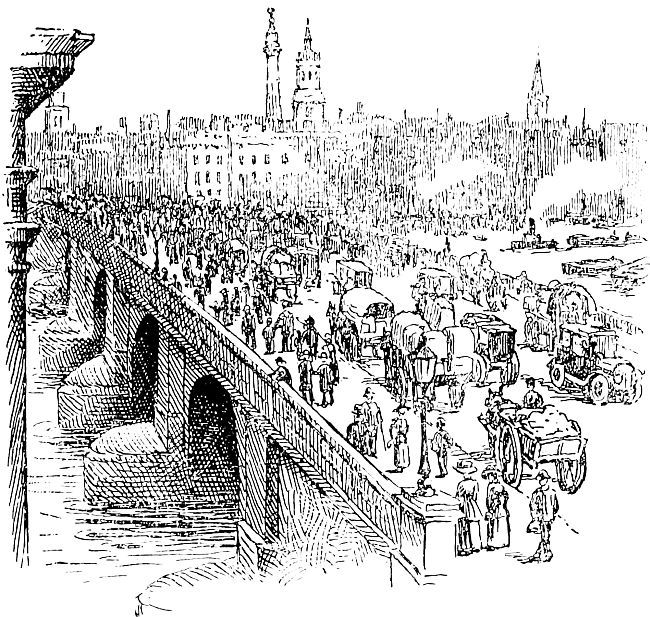

LONDON BRIDGE IN MODERN TIMES.

The Bridge, as the only approach to the city from the south, was the scene of many wonderful pageants and processions, as our victorious Kings came back from their wars with France, or returned to England with their brides from overseas. Such a magnificent spectacle was the crossing in state of Henry V. after the great victory of Agincourt in the year 1415. The battle, as most of you know, took place in October of that year, and at the end of November the King passed over the Bridge at the head of his most distinguished prisoners and his victorious soldiers, amid the tumultuous rejoicing of London’s jubilant citizens.

Yet another strange scene was enacted when Wat Tyler, at the head of his tens of thousands, passed over howling and threatening, after being temporarily held back by the gates which stood at the south end of the Bridge.

So the old Bridge lasted on, living through momentous days, till, in the year 1832, it was removed to give place to the new London Bridge which had been erected sixty yards to the westwards.