CHAPTER SIX

How the City grew (in the Middle Ages)

LONDON in that period which we speak of as the Middle Ages was indeed a remarkable city. Dotted about all over it, north and south, west and east, were great monasteries and nunneries and churches, for in those days the Church was a tremendous power in the land; while huddled together within its confines were shops, houses, stores, palaces, all set down in a bewildering confusion. Of palaces there was indeed a profusion; in fact, London might well have been called a City of Palaces. But they were not arranged in long lines along the banks of canals, as were those of Venice, nor round fine stately squares, as in Florence, Genoa, and other famous cities of the Continent. London’s palaces nestled in the city’s narrow, muddy lanes, between the warehouses of the merchants and the hovels of the poor. They paid little or no attention to external beauty, but within they were splendid structures.

Now, what did this mean? That the common people of London constantly came into contact with the great ones of the land. The apprentice, sent on an errand by his master, might at any moment be held up as Warwick the King-maker, let us say, emerged from his gateway, followed by a train of several hundred retainers all decked out in his livery; or the Queen and her ladies might pass in gay procession to view a tournament in the fields just north of the Chepe. In that way the citizens learned right from their earliest day that London was not the only place in England, that there were other folk in the land, and great ones too, who were not London merchants and craftsmen.

This constant reminder that they were simply part and parcel of the great realm of England did this for the people of London: it made them keen on politics, always ready to take sides in any national strife. On the other hand, it gave them great pride. The citizens soon discovered that, though they were not the only folk in the land, they counted for much, for whatever side or cause they supported always won in the end. This, of course, more firmly cemented the position of London as the foremost spot in the kingdom.

Very beautiful indeed were some of the palaces, or inns, as they were quite commonly called. They were in no sense of the word fortresses; their gates opened straight on to the narrow, muddy lanes without either ditch or portcullis. Inside there was usually a wide courtyard, surrounded by the various buildings. Unfortunately the Great Fire and other calamities have not spared us much whereby we can recall such palaces to mind. Staple Inn, whose magnificent timbered front is still one of London’s most precious relics, is of a later date, but possesses many of the medieval characters. Crosby Hall, in Bishopsgate Street, was a fine specimen. This was erected in the fifteenth century by a grocer and Lord Mayor, Sir John Crosby, a man of great wealth; and for some time it was the residence of Richard III. For many years it remained to show us the exceeding beauty of a medieval dwelling; but, alas, that too has gone the way of all the others! A portion of it, the great Hall, has been re-erected in Chelsea.

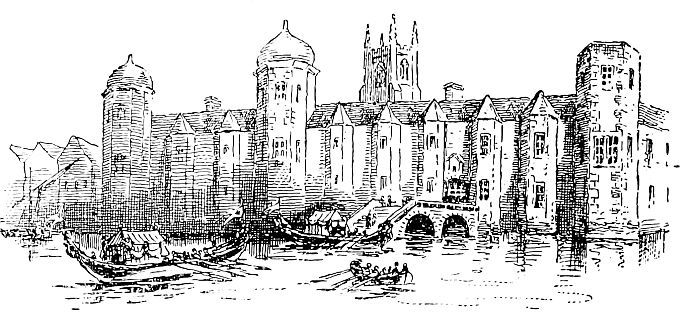

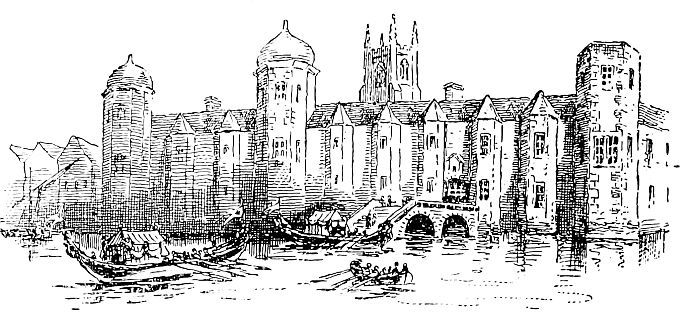

BAYNARD’S CASTLE BEFORE THE GREAT FIRE.

Otherwise most of these palaces remain only as a name. Baynard’s Castle, one of the most famous of all, which stood close to the western end of the river-wall, lasted for 600 years from the Norman Conquest to the time of the Great Fire, but it is only remembered in the name of a wharf and a ward of the city. Coldharbour Palace, which stood in Thames Street with picturesque gables overhanging the River, passed from a great place in history down to oblivion.

So with all the rest of these elaborate, historic palaces, about which we can read in the pages of Stow, that delightful chronicler of London and her ways; they either perished in the flames or were pulled down to make way for hideous commercial buildings.

London in the Middle Ages passed through a period of great prosperity; but, at the same time, it suffered terribly through pestilence, famine, rebellions, and so on. The year 1349 saw a dreadful calamity in the shape of the “Black Death”—a kind of plague which came over from Asia. The narrow, dirty lanes, with their stinking, open ditches, the unsatisfactory water-supply, all caused the dread disease to spread rapidly; and a very large part of London’s citizens perished.

Moreover, famine followed in the path of the pestilence which stalked through the land. So great was the toll of human life throughout England that there were but few left to work on the land; and London, which depended for practically all its supplies on what was sent from afar, suffered severely. Still, despite all these troubles, the Middle Ages must be regarded as part of the “good old times,” when England was “merry England” indeed. True, the citizens had to work hard, and during long hours, but they found plenty of time for pleasure. Those of you who have read anything of Chaucer’s “Canterbury Tales” will know something of the brightness of life in those times, of the holidays, the pageants and processions, the tournaments, the fairs, the general merrymaking.

All of which, of course, was due to good trade. The city which the River had made was growing in strength. London now made practically everything it needed, and within its walls were representatives of practically every calling. As Sir Walter Besant says in his fine book, “London”: “There were mills to grind the corn, breweries for making the beer; the linen was spun within the walls, and the cloth made and dressed; the brass pots, tin pots, iron utensils, and wooden platters and basins, were all made in the city; the armour, with its various pieces, was hammered out and fashioned in the streets; all kinds of clothes, from the leathern jerkin of the poorest to the embroidered robes of a princess, were made here....

“There was no noisier city in the whole world; the roar and the racket of it could be heard afar off, even at the risings of the Surrey hills or the slope of Highgate. From every lane rang out, without ceasing, the tuneful note of the hammer and the anvil; the carpenters, not without noise, drove in their nails, and the coopers hooped their casks; the blacksmith’s fire roared; the harsh grating of the founders set the teeth on edge of those who passed that way; along the river bank, from the Tower to Paul’s Stairs, those who loaded and those who unloaded, those who carried the bales to the warehouses, those who hoisted them up; the ships which came to port and the ships which sailed away, did all with fierce talking, shouting, quarrelling, and racket.”

As we picture the prosperity of those medieval days there comes into our minds that winding silver stream which made such prosperity possible, and we seem to see the River Thames crowded with ships from foreign parts, many of them bringing wine from France, Spain, and other lands, for wine was one of the principal imports of the Middle Ages, and filling up the great holds of their empty vessels with England’s superior wool; others from Italy, laden with fine weapons and jewels, with spices, drugs, and silks, and all wanting our wool. A few of those ships in the Pool were laden with coal, for in the Middle Ages this new fuel—sea-coal, as it was called to distinguish it from the ordinary wood charcoal—made its appearance in London. Nor did London take to it at first. In the reign of Edward I. the citizens sent a petition, praying the King to forbid the use of this “nuisance which corrupteth the air with its stink and smoke, to the great detriment of the health of the people.”

But the advantages of the sea-coal rapidly outweighed the disadvantages with the citizens, and the various proclamations issued by sovereigns came to nought. Before long several officials were appointed to act as inspectors of the new article of commerce as it came into the wharves. The famous Dick Whittington and various other prominent citizens of London made large fortunes from their coal-boats.