CHAPTER TWELVE

The Riverside of To-day

THE Riverside of to-day is noticeable for many things, but for nothing more so than the very great difference between the two banks. On the one hand we have a magnificent Embankment sweeping round through almost the entire length of the River’s passage through London, with large and important buildings surmounting the thoroughfare; while on the other hand we have nothing but a huddled collection of commercial buildings, right on the water’s edge—unimposing, dingy, and dismal, save in the one spot where the new County Hall breaks the ugly monotony and gives promise of better things in future for the Surrey shore.

The Embankment on the Middlesex side may perhaps be said to be one of the outcomes of the Great Fire, for, though its construction was not undertaken till 1870, it was one of the main improvements suggested by Sir Christopher Wren in his scheme for the rebuilding of London. The Victoria Embankment, which sweeps round from Blackfriars to Westminster, is a mile and a quarter long. Its river face consists of a great granite wall, 8 feet in thickness, with tunnels inside it for the carrying of sewers, water-mains, gas-pipes, etc., all of which can be reached without interfering with that splendid wide road beneath which the Underground Railway runs. There is a continuation of the Embankment on the south side from Westminster to Vauxhall, known as the Albert Embankment, while on the north it runs, with some interruptions, as far as Chelsea.

One of the most interesting sights of the Embankment is Cleopatra’s Needle—a tall stone obelisk, which stands by the water’s edge. This stone, one of the oldest monuments in the world, stood originally in the ancient city of On, in Egypt, and formed part of an enormous temple to the sun-god. Later it was shifted with a similar stone to Alexandria, there to take a place in the Cæsarium—the temple erected in honour of the Roman Emperors. Centuries passed: the Cæsarium fell into ruins, and Cleopatra’s obelisk lay forgotten in the sand. Eventually it was offered to this country by the Khedive of Egypt, but the task of transporting it was so difficult that nothing was done till 1877-8, when Sir Erasmus Wilson undertook the enormous cost of the removal. It has nothing to do with Cleopatra.

Of the bridges over the River we have already dealt with the most famous—the remarkable old London Bridge which stood for so many centuries and only came to an end in 1832. Westminster Bridge, built in 1750, was the first rival to the ancient structure, and though it was but a poor affair it made the City Council very dissatisfied with their possession. Nor was this surprising, for the old bridge had got into a very bad state, so that in 1756 the City Fathers decided to demolish all the buildings on the bridge, and to make a parapet and proper footwalks.

Up to the time of King George II. there was at Westminster merely a jetty or landing-stage used in connection with the ferry that was used in place of the ancient ford; but during this King’s reign Westminster, and, shortly afterwards, Blackfriars Bridge, came into being. Battersea and Vauxhall, Waterloo (built two years after the battle), Southwark, Chelsea, and Lambeth followed in fairly rapid succession. Of these, Westminster, Blackfriars, Battersea, Vauxhall, and Southwark have already been rebuilt.

Old Vauxhall Bridge was the first cast-iron bridge ever built; Wandsworth was the first lattice bridge; Waterloo Bridge the first ever made with a perfectly level roadway. Hungerford Bridge, which stretched where now that atrociously ugly iron structure, the Charing Cross Railway bridge, defiles the River, was originally designed by Brunel, the eminent engineer, to span the gorge over the Avon at Clifton, but it was eventually placed in position across the Thames. When the atrocity was built the suspension bridge was taken back to Clifton, where it now hangs like a spider’s web over the mighty gap in the hills.

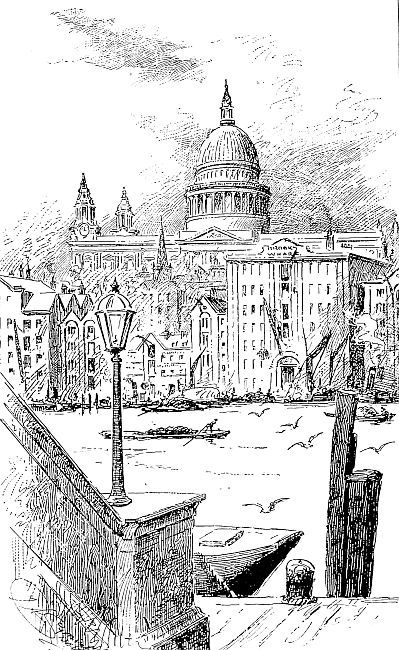

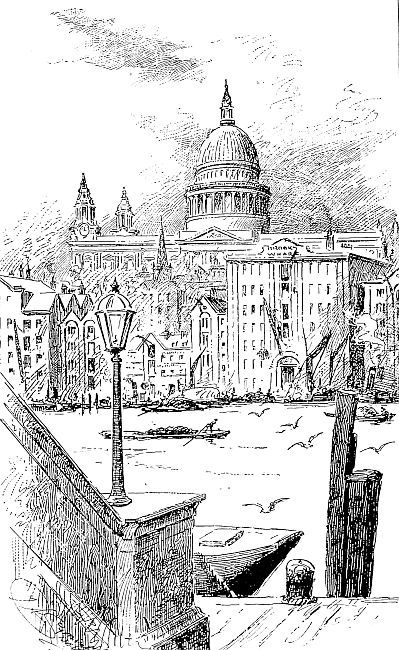

ST. PAUL’S FROM THE SOUTH END OF SOUTHWARK BRIDGE.

Until the close of the nineteenth century London Bridge enjoyed the distinction of being the lowest bridge on the River’s course; but in 1894 the wonderful Tower Bridge was opened. This mighty structure, which was commenced in 1886, cost no less than £830,000. In its construction 235,000 cubic feet of granite and other stone, 20,000 tons of cement, 10,000 yards of concrete, 31,000,000 bricks, and 14,000 tons of steel were used. In its centre are two bascules, each weighing 1,200 tons, which swing upwards to allow big ships to pass into the Pool. Although these enormous bascules, the largest in the world, weigh so much, they work by hydraulic force as smoothly and easily as a door opens and shuts.

Of the buildings on the south side of the River practically none are worthy of notice save the Shot Tower—where lead-shot is made by dropping the molten metal from the top of the shaft—the new County Hall, and St. Thomas’s Hospital at Westminster. The County Hall is a splendid structure, one of the finest of its kind in the whole world. It possesses miles of corridors, hundreds of rooms, and what is more, a magnificent water frontage. The architect is Mr. Ralph Knott. St. Thomas’s Hospital, which stands close to it, is one of a number of excellent hospitals in various parts of London. When in 1539 the monasteries were closed, London was left without anything in the way of hospitals, or alms-houses, or schools; for the care of the sick, the infirm, and the young had always been the work of the monks and the nuns. In consequence, London suffered terribly. Matters became so extremely serious that the City Fathers approached the King with a view to the return of some of these institutions. Their petition was granted, and King Henry gave back St. Bartholomew’s, Christ’s Hospital, and the Bethlehem Hospital. Later King Edward VI. allowed the people to purchase St. Thomas’s Hospital—the hospital of the old Abbey of Bermondsey. When in 1871 the South-Eastern Railway Company purchased the ground on which the old structure stood, a new and more convenient building was erected on the Albert Embankment opposite the Houses of Parliament.

As we stand once more on Westminster Bridge and see the two great places, one on each side, where our lawmakers sit—those of the Nation and those of the great City—our glance falls on the dirty water of old Father Thames slipping by; and we think to ourselves that great statesmen may spring to fame and then die and leave England the poorer, governments good and bad may rise and fall, changes of all sorts may happen within these two stately buildings, the very stones may crumble to dust, but still the River flows on—silent, irresistible.