CHAPTER ELEVEN

Royal Westminster—The Houses of Parliament

WHEN in the eleventh century Edward the Confessor built the palace from which to survey the erection of his beloved Abbey, he little dreamed that upon the very spot would meet the Parliament of an Empire greater even than Rome; nor did he realize that through several centuries Westminster Palace would be the favourite home of the Kings and Queens of England.

William Rufus added to the Confessor’s edifice, and also partially built the walls of the Great Hall, which is the sole thing that remains of the ancient fabric. Other Kings enlarged the palace from time to time. Stephen erected the Chapel of St. Stephen, in which met the Commons from the time of Edward VI. till the year 1834, when a terrible fire wiped out practically the whole of the ancient Palace of Westminster.

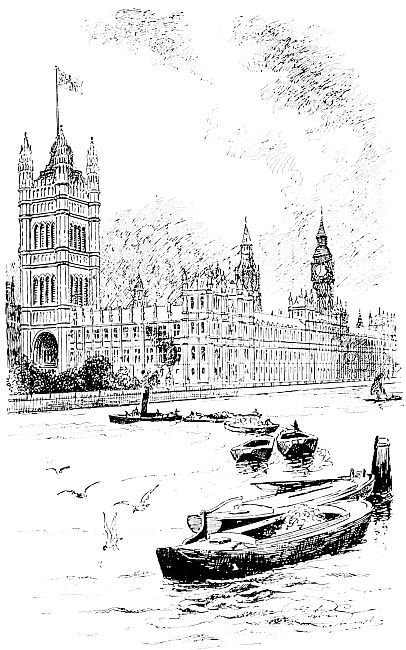

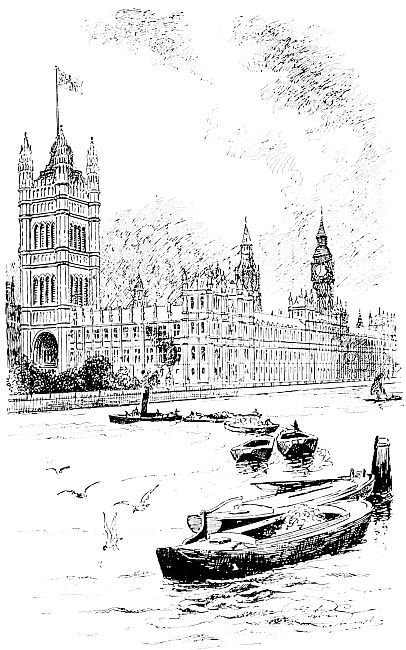

THE HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT.

To-day, when we stand on Westminster Bridge or Lambeth Bridge, and survey the huge building which provides London with one of its greatest landmarks, we are looking at a new Palace: from the River not a stone of the old structure is visible. A magnificent Palace it is too! Its towers, one at each end, rise high into the air, one of them 320 feet high, the other 20 feet more; and its buildings cover a matter of 8 acres. From Westminster Bridge we see the whole of the river front, 900 feet long, with the famous “terrace” in front, where in summer the Members of Parliament stroll and take tea with their friends.

Westminster Hall, which fortunately survived the disastrous fire of 1834, is on the side farthest from the River: it runs parallel with the House of Commons, and projects from the main building just opposite the end of the Henry VII. Chapel in the Abbey.

If we enter the Parliament buildings we shall very possibly do so by the famous hall known as St. Stephen’s Hall—built on the site of the ancient House of Commons. Westminster Hall then lies to our left, as we enter, down a flight of steps.

Let us descend for a few moments, for the Hall is perhaps the finest of its kind in all our land. Its vast emptiness silences the words which rise to our lips: we feel instinctively that this is a place of wonderful memories. Our eyes travel along the mighty, carved-oak roof which spans the great width of the building, and we can scarcely believe that this roof was built so long ago as the time of Richard II., or even earlier, and that it is still the actual timbers we see in places.

What stories could these ancient stones beneath our feet tell us, had they but the power! What tales of joy and what tales of terrible tragedy! Here were held many of the festivities which followed the coronation ceremonies in the Abbey. Henry III. here showed to the citizens his bride, Eleanor of Provence, when “there were assembled such a multitude of the nobility of both sexes, such numbers of the religious, and such a variety of stage-players, that the City of London could scarcely contain them.... Whatever the world pours forth of pleasure and glory was there specially displayed.” And yet a few years later saw that same Henry taking part in a vastly different spectacle—when, in the presence of a gathering equally distinguished, he was compelled to watch the Archbishop of Canterbury as he threw to the stone floor of the Hall a lighted torch, with these words: “Thus be extinguished and stink and smoke in hell all those who dare to violate the charters of the Kingdom.”

A plate let into the floor tells us that on that spot stood Wentworth, Earl of Strafford, strong Minister of a weak King, when he was tried for his life; while upon the stairs which we have descended is another tablet to mark the spot whence that weak King himself, Charles I., heard his death sentence. Here, too, were tried William Wallace, Thomas More, and Warren Hastings, while just outside in Old Palace Yard the half-demented Guido Fawkes and the proud, scholarly Sir Walter Raleigh met their deaths.

Returning to St. Stephen’s Hall, which is lined with the statues of the great statesmen who were famous in the older chamber, and passing up another flight of steps, we find ourselves in the octagonal Central Hall, or, as it is more usually called, the Lobby. Here we are practically in the middle of the great pile of buildings. To our right, as we enter, stretches the House of Lords and all the apartments that pertain to it—the Audience Chamber, the Royal Robing Room, the Peers’ Robing Room, the House of Lords Library—ending in the stately square tower, known as the Victoria Tower. To our left lies the House of Commons and all its committee, dining, smoking, reading-rooms, etc., ending in the famous “Big Ben” tower. “Big Ben” is, of course, known to everybody. Countless thousands have heard his 13½ tons of metal boom out the hour of the day, and have set their watches right by the 14-foot minute-hands of the four clock-faces, which each measure 23 feet across.

The House of Lords itself is a fine building, 90 feet long and 45 feet wide, its walls and ceiling beautifully decorated with paintings representing famous scenes from our history. At one end is the King’s gorgeous throne, and beside it, slightly lower, those of the Queen and the Prince of Wales. Just in front is the famous “Woolsack,” an ugly red seat, stuffed with wool, as a reminder of the days when wool was the chief source of the nation’s wealth. On this, when the House is in session, sits the Lord Chancellor of England, who presides over the assembly.

The House of Commons is not quite so ornate: here the benches are upholstered in a quiet green. At the far end is the Speaker’s Chair. The Speaker, as you probably know, is the chairman of the House of Commons, the member who has been chosen by his fellows to control the debates and keep order in the House. In front of the Speaker’s Chair is a table, at which sit three men in wigs and gowns, the Clerks of the House. On the table lies the Mace—the heavy staff which is the emblem of authority.