CHAPTER ONE

Stripling Thames

JUST where the Thames starts has always been a matter of argument, for several places have laid claim to the honour of holding the source of this great national possession.

About three miles south-west of Cirencester, and quite close to that ancient and famous highway the Ackman Street (or Bath fosseway), there is a meadow known as Trewsbury Mead, lying in a low part of the western Cotswolds, just where Wiltshire and Gloucestershire meet; and in this is situated what is commonly known as “Thames Head”—a spring which in winter bubbles forth from a hollow, but which in summer is so completely dried by the action of the Thames Head Pump, which drains the water from this and all other springs in the neighbourhood, that the cradle of the infant Thames is usually bone-dry for a couple of miles or more of its course. This spot is usually recognized as the beginning of the River.

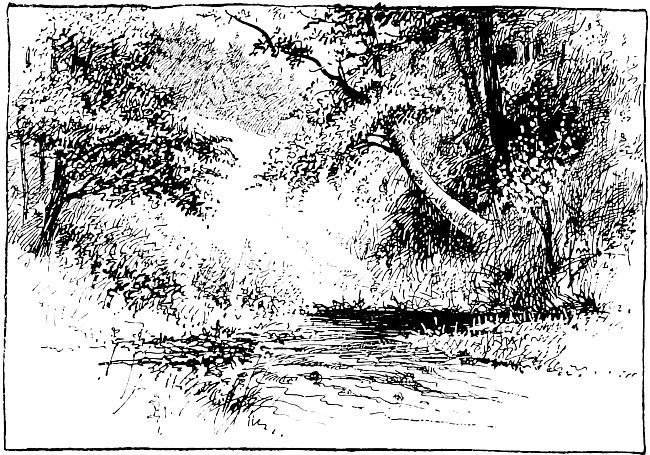

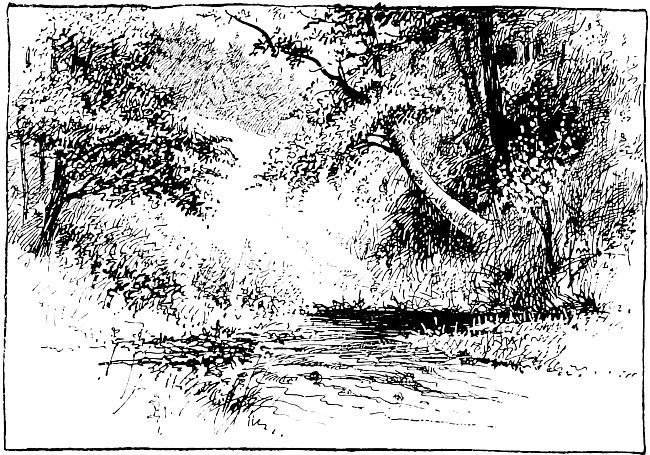

THAMES HEAD.

If, however, we consider that the source of a river is the point at greatest distance from the mouth we shall have to look elsewhere; for the famous “Seven Streams” at the foot of Leckhampton Hill, from which comes the brook later known as the River Churn, can claim the distinction of being a few more miles from the North Sea; and this distinction has frequently been recognized as sufficient to grant the claim to be the true commencement.

But the Churn has always been the Churn (indeed, the Romans named the neighbouring settlement from the stream—Churn-chester or Cirencester); and no one has ever thought of calling it the Thames. Whereas the stream beginning in Trewsbury Mead has from time immemorial been known as the Thames (Isis is only an alternative name, not greatly used in early days); and so the verdict of history seems to be on its side, whatever geography may have to say.

Nevertheless it matters little which can most successfully support its claim. What does matter is that Churn, and Isis, and Leach, and Ray, and Windrush, and the various other feeders, give of their waters in sufficient quantity to ensure a considerable river later on. From the point of view of their usefulness both the main stream and the tributaries are negligible till we come to Lechlade, for only there does navigation and consequently trade begin. But if the stream is not very useful, it is exceedingly pretty, with quaint rustic bridges spanning its narrow channel, and fine old-world mills and mansions and cottages and numbers of ancient churches on its banks.

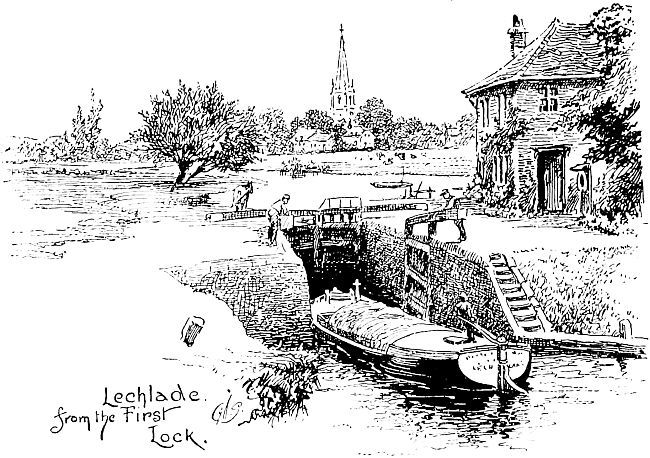

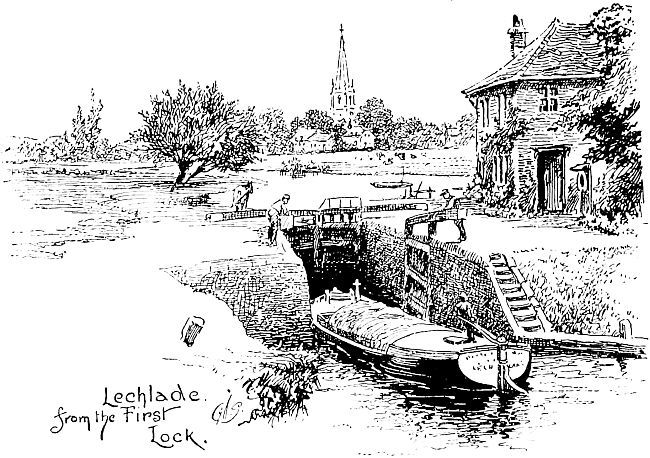

LECHLADE FROM THE FIRST LOCK.

The first place of any size is the little town of Cricklade, which can even boast of two churches. Here the little brooks of infant Thames (or Isis) and Churn join forces, and yield quite a flowing stream. At Lechlade the rivulet is joined by the Colne, and its real life as a river commences. From now on to London there is a towing-path beside the river practically the whole of the way, for navigation by barges thus early becomes possible.

From Lechlade onwards to Old Windsor, a matter of about a hundred miles, the upper Thames has on its right bank the county of Berkshire, with its beautiful Vale of the White Horse, remembered, of course, by all readers of “Tom Brown’s Schooldays.” On the left bank is Oxfordshire as far as Henley, and Buckinghamshire afterwards.

In and out the “stripling Thames” winds its way, clear as crystal as it slips past green meadows and little copses. There is very little to note as we pass between Lechlade and Oxford, a matter of forty miles or so. Owing to the clay bed, not a town of any sort finds a place on or near the banks. Such villages as there are stand few and far between.

Just past Lechlade there is Kelmscott, where William Morris dwelt for some time in the Manor House; and the village will always be famous for that. There in the old-world place he wrote the fine poems and tales which later he printed in some of the most beautiful books ever made, and there he thought out his beautiful designs for wall-papers, carpets, curtains, etc. He was a wonderful man, was William Morris, a day-dreamer who was not content with his dreams until they had taken actual shape.

KELMSCOTT MANOR.

On we go past New Bridge, which is one of the oldest, if not the very oldest, of the many bridges which cross the River. Close at hand the Windrush joins forces, and the River swells and grows wider as it sweeps off to the north. Away on the hill on the Berkshire side is a little village known as Cumnor, which is not of any importance in itself, but which is interesting because there once stood the famous Cumnor Hall, where the beautiful Amy Robsart met with her untimely death, as possibly some of you have read in Sir Walter Scott’s novel “Kenilworth.” Receiving the Evenlode, the River bends south again, and a little later we pass Godstow Lock, not far from which are the ruins of Godstow Nunnery, where Fair Rosamund lived and was afterwards buried. Between Godstow and Oxford is a huge, flat piece of meadowland, known as Port Meadow: this during the War formed one of our most important flying-grounds.

Henceforward the upper Thames is interrupted at fairly frequent intervals by those man-made contrivances known as locks—ingenious affairs which in recent years have taken the place of or rather supplemented the old-fashioned weirs. For any river which boasts of serious water traffic the chief difficulty, especially in summer-time, has always been that of holding back sufficient water to enable the boats to keep afloat. Naturally with a sloping bed the water runs rapidly seawards, and if the supply is not plentiful the river soon tends to become shallow or even dry. In very early days man noticed this, and, copying the beaver, he erected dams or weirs to hold back the water, and keep it at a reasonable depth. And down through the centuries until comparatively recent years these dams or weirs sufficed. As man progressed he fashioned his weirs with a number of “paddles” which lifted up and down to allow a boat to pass through. When the craft was moving downstream just one or two paddles were raised, and the boat shot through the narrow opening on the crest of the rapids thus formed; but when the boat was making its way upstream more paddles were raised so that the rush of water was not so great, and the boat was with difficulty hauled through the opening in face of the strong current. This very picturesque but primitive method lasted until comparatively recent years. Now the old paddle-locks have gone the way of all ancient and delightful things, and in their places we have the thoroughly effective “pound-locks”—affairs with double gates and a pool or dock in between—which in reality convert the river into a long series of water-terraces or steps, dropping lower and lower the nearer we approach the mouth.