CHAPTER TWO

Oxford

ONE hundred and twelve miles above London Bridge there is the second most celebrated city on the banks of the Thames—Oxford, the “city of spires,” as it has been called. By no means a big place, it is famous as the home of our oldest University.

Seen from a distance, Oxford is a place of great beauty, especially when the meadows round about are flooded. Then it seems to rise from the water like some English Venice. Nor does the beauty grow less as we approach closer, or when we view the city from some other point. Always we see the delicate spires of the Cathedral and the churches, the beautiful towers of the various colleges, the great dome of the Radcliffe Camera, all of them nestling among glorious gardens and fine old trees.

The question at once comes into our minds, Why is it that there is a famous city here? Why should such a place as this, right out in the country, away from what might be called the main arteries of the life of England, be one of the most important seats of learning?

To understand this we must go back a long way, and we must ask ourselves the question, Why was there ever anything—even a village—here at all? If we think a little we shall see that in the early days, when there were not very many good roads, and when there were still fewer bridges, the most important spots along a river were the places where people could cross: that is to say, the fords. To these spots came the merchants with their waggons and their trains of pack-horses, the generals with their armies, the drovers with their cattle, the pilgrims with their staves. All and sundry, journeying from place to place, made for the fords, while the long stretches of river bank between these places were never visited and seldom heard of.

Now, what made a ford? Shallow water, you say. Yes, that is true. But shallow water was not enough. It was necessary besides that the bed of the stream should be firm and hard, so that those who wished might find a safe crossing. And places where such a bottom could be found were few and far between along the course of the Thames. Practically everywhere it was soft clay in which the feet of the men and the animals and the wheels of the waggons sank deep if they tried to get from bank to bank.

But, just at the point where the Thames bends southwards, just before the Cherwell flows into it, there is a stretch of gravel which in years gone by made an excellent ford and provided a suitable spot on which some sort of a settlement might grow.

How old that settlement is no one knows. Legend tells us that a Mercian saint by the name of Frideswide, together with a dozen companions, founded a nunnery here somewhere about the year 700. Certainly the village is mentioned under the name of Oxenford (that is, the ford of the oxen) in the Saxon Chronicle, a book of ancient history written about a thousand years ago; and we know that Edward the Elder took possession of it, and, building a castle and walls, made a royal residence. So that it is a place of great antiquity.

Another question that comes into our minds is this, When did Oxford become the great home of learning which it has so long been? Here again the truth is difficult to ascertain. Legend tells us that King Alfred founded the schools, but that is rather more than doubtful. We do know that during the twelfth century there was a great growth in learning. Right throughout Europe great schools sprang into existence, one of the most important being that in Paris. Thither went numbers of Englishmen to learn, and they, returning to their own land, founded schools in different parts, usually in connection with the monasteries and the cathedrals. Such a school was one which grew into being at St. Frideswide’s monastery at Oxford. Also King Henry I. (Beauclerc—the fine scholar—as he was called) built a palace at Oxford, and there he gathered together many learned men, and from that time people gradually began to flock to Oxford for education. They tramped weary miles through the forest, across the hills and dales, and so came to the little town, only to find it crowded out with countless others as poor as themselves; but they were not disheartened. There being no proper places for teaching, they gathered with their masters, also equally poor, wherever they could find a quiet spot, in a porch, or a loft, or a stable; and so the torch was handed on. Gradually lecture-rooms, or schools as they were called, and lodging-houses or halls, were built, and life became more bearable. Then in 1229 came an accident which yet further established Oxford in its position. This accident took the form of a riot in the streets of Paris, during the course of which several scholars of Paris University were killed by the city archers. Serious trouble between the University folk and the Provost of Paris came of this; and, in the end, there was a very great migration of students from Paris to Oxford; and, a few years after, England could boast of Oxford as a famous centre of learning.

But it was not till the reign of Henry III. that a real college, as we understand it, came into being. Then, in the year 1264, one Walter de Merton gathered together in one house a number of students, and there they lived and were taught; and thus Merton, the oldest of the colleges, began. Others soon followed—Balliol, watched over by the royal Dervorguilla; University College, founded by William of Durham, who was one to come over after the Paris town and gown quarrel; New College; and so on, college after college, until now, as we wander about the streets of this charming old city, it seems almost as if every other building is a college. And magnificent buildings they are too, with their glorious towers and gateways, their beautiful stained-glass windows, their panelled walls. To wander round the city of Oxford is to step back seemingly into a forgotten age, so worn and ancient-looking are these piles of masonry. Modern clothes seem utterly out of place in such an antique spot.

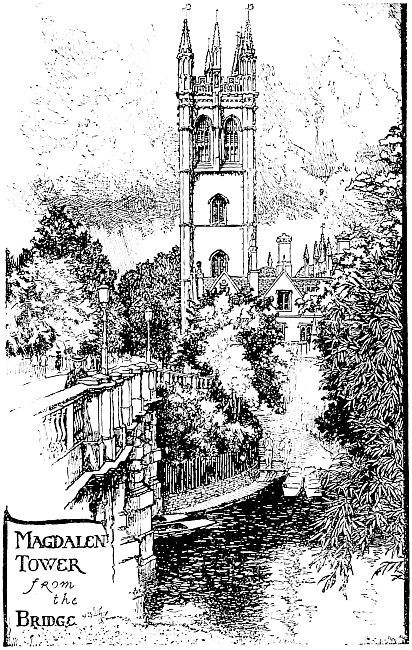

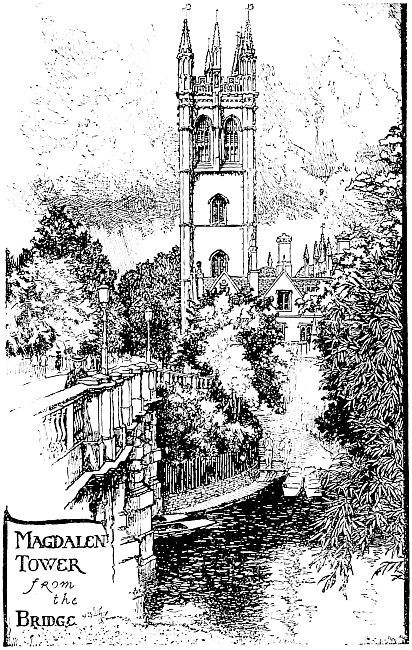

MAGDALEN TOWER FROM THE BRIDGE.

Different folk, of course, will regard different colleges as holding pride of place; but, I am sure, all will agree that one of the finest is Magdalen College, a beautiful building standing amid [252]

[253]cool, green meadows. Very fine indeed is the great tower, built in 1492, from the top of which every May morning the College choir sings a glad hymn of praise; and very fine too are the cloisters below, and the lovely leafy walks in whose shade many famous men have walked in their youthful days.

If we grant to Magdalen its claim to be the most beautiful of the colleges, we must undoubtedly recognize Christ Church as the most magnificent. We shall see something of the splendour of Cardinal Wolsey’s ideas with regard to building when we talk about his palace at Hampton Court, and we need feel no surprise at the grandeur of Christ Church. Unfortunately, Wolsey’s ideas were never carried out: his fall from favour put an end to the work when but three sides of the Great Quadrangle had been completed; and then for just on a century the fabric stood in its unfinished state—a monument to o’erleaping ambition. Nevertheless it was completed, and though it is not all that Wolsey intended it to be, it is still one of the glories of the city. Built round about the old Cathedral, it stands upon the site of the ancient St. Frideswide’s priory.

The famous “Tom Tower” which stands in the centre of the front of the building was not a part of the original idea: it was added in 1682 by Dr. Fell, according to the design of Sir Christopher Wren, the architect of St. Paul’s Cathedral. “Tom Tower” is so called because of its great bell, brought from Osney Abbey. “Great Tom,” which weighs no less than six tons, peals forth each night at nine o’clock a hundred and one strokes, and by the time of the last stroke all the College gates are supposed to be shut and all the undergraduates safely within the College buildings.

The most wonderful possession of Christ Church is its glorious “Early English” hall, in which the members of the College dine daily: 115 feet long, 40 feet broad, and 50 feet high, it is unrivalled in all England, with perhaps the exception of Westminster Hall. Here at the tables have sat many of England’s most famous men—courtiers, writers, politicians, soldiers, artists—and the portraits of a number of them, painted by famous painters, look down from the ancient walls.

But these are only two of the colleges. At every turn some other architectural beauty, some dream in stone, discloses itself, for the colleges are dotted about all over the centre of the town, and at every other corner there is some spot of great interest. To describe them all briefly would more than fill the pages of this book.

Nor are colleges the only delightful buildings in this city of beautiful places. There is the famous Sheldonian Theatre, built from Wren’s plans: this follows the model of an ancient Roman theatre, and will seat four thousand people. There is the celebrated Bodleian Library, founded as early as 1602, and containing a rich collection of rare Eastern and Greek and Latin books and manuscripts. The Bodleian, like the British Museum, has the right to call for a copy of every book published in the United Kingdom.

But Oxford has known a life other than that of a university town: it has been in its time a military centre of some importance. As we sweep round northwards in the train from London, just before we enter the city, the great square tower of the Castle stands out, one of the most prominent objects in the town. And it is really one of the most interesting too, though few find time to visit it. So absorbed are most folk in the churches and chapels, the libraries and college halls, with their exquisite carvings and ornamentations and their lovely gardens, that they forget this frowning relic of the Conqueror’s day—the most lasting monument of the city. Built in 1071 by Robert d’Oilly, boon companion of the Conqueror, it has stood the test of time through all these centuries. Like Windsor, that other Norman stronghold, it has seen little enough of actual fighting: in Oxford the pen has nearly always been mightier than the sword.

One brief episode of war it had when Stephen shut up his cousin, the Empress Maud, within its walls in the autumn of 1142. Then Oxford tasted siege if not assault, and the castle was locked up for three months. However, the River and the weather contrived to save Maud, for, just as provisions were giving out and surrender was only a matter of days, there came a severe frost and the waters were thickly covered. Then it was that the Empress with but two or three white-clad attendants escaped across the ice and made her way to Wallingford, while her opponents closely guarded the roads and bridges.

Nor in our consideration of the glories of this beloved old city must we forget the River—for no one in the place forgets it. Perhaps we should not speak of the River, for Oxford is the fortunate possessor of two, standing as it does in the fork created by the flowing together of the Thames and the Cherwell. The Thames, as we have already seen, flows thither from the west, while the Cherwell makes its way southwards from Edgehill; and, though we are accustomed to think of the Thames as the main stream, the geologists, whose business it is to make a close study of the earth’s surface, tell us that the Cherwell is in reality the more important of the two; that down its valley in the far-away past flowed a great river which with the Kennet was the ancestor of the present-day River; that the tributary Thames has grown so much that it has been able to capture and take over as its own the valley of the Cherwell from Oxford onwards to Reading. But that, of course, is a story of the very dim past, long before the days of history.

The Cherwell is a very pretty little stream, shaded by overhanging willows and other trees, so that it is usually the haunt of pleasure, the place where the undergraduate takes his own or somebody else’s sister for an afternoon’s excursion, or where he makes his craft fast in the shade in order that he may enjoy an afternoon’s quiet reading. A walk through the meadows on its banks is, indeed, something very pleasant, with the stream on one side of us and that most beautiful of colleges, Magdalen, on the other. Here as we proceed down the famous avenue of pollard willows, winding between two branches of the stream, we can hear almost continuously the singing of innumerable birds, for the Oxford gardens and meadows form a veritable sanctuary in which live feathered friends of every sort.

But the Thames (or Isis as it is invariably called in Oxford) is the place of more serious matters. To the rowing man “the River” means only one thing, and really only a very short space of that: he is accustomed to speak of “the River” and “the Cher,” and with him the latter does not count at all. Everybody in the valley, certainly every boy and girl, knows about the Oxford and Cambridge Boatrace, which is held annually on the Thames at Putney, when two selected crews from the rival universities race each other over a distance. Probably quite a few of us have witnessed the exciting event. Well, “Boatrace Day” is merely the final act of a long drama, nearly all the scenes of which take place, not at Putney, but on the river at the University town. For the Varsity “eight” are only chosen from the various college crews after long months of arduous preparation. Each of the colleges has its own rowing club, and the college crews race against each other in the summer term. A fine sight it is, too, to see the long thin “eights” passing at a great pace in front of the beautifully decorated “Barges,” which are to the college rowing clubs what pavilions are to the cricket clubs.

These “barges,” which stretch along the river front for some considerable distance, resemble nothing so much as the magnificent houseboats which we see lower down the river at Henley, Maidenhead, Molesey, etc. They are fitted up inside with bathrooms and dressing-rooms, and comfortable lounges and reading-rooms, while their flat tops are utilised by the rowing men for sitting at ease and chatting to their friends. Each college has its own “barge,” and it is a point of honour to make it and keep it a credit to the college. The long string of “barges” form a very beautiful picture, particularly when the river is quiet, and the finely decorated vessels with their background of green trees are reflected in the smooth waters.

May is the great time for the River at Oxford, for then are held the races of the senior “crews” or “eights.” Then for a week the place, both shore and stream, is gay with pretty dresses and merry laughter, for mothers and sisters, cousins and friends, flock to Oxford in their hundreds to see the fun. But to the rowing man it is a time of hard work—with more in prospect if he is lucky; for, just as the “eights” of this week have been selected from the crews of the February “torpids” or junior races, so from those doing well during “eights week” may be chosen the University crew—the “blues.”

Many have been the voices which have sung the praises of the “city of spires,” for many have loved her. None more so perhaps than Matthew Arnold, whose poem “The Scholar Gypsy”—the tale of a University lad who was by poverty forced to leave his studies and join himself to a company of vagabond gipsies, from whom he gained a knowledge beyond that of the scholars—is so well known. Says Arnold of the city: “And yet as she lies, spreading her gardens to the moonlight, and whispering from her towers the last enchantments of the Middle Ages, who will deny that Oxford, by her ineffable charm, keeps ever calling us nearer to the true goal of all of us, to the ideal, to perfection—to beauty, in a word?”

There are many interesting places within walking distance of Oxford, but perhaps few more delightful to the eye than old Iffley Church. This ancient building with its fine old Norman tower is a landmark of the countryside and well deserves the attention given to it.