CHAPTER FOUR

Reading

READING is without doubt the most disappointing town in the whole of the Thames Valley. It has had such a full share of history, far more than other equally famous towns; has been favoured by the reigning monarch of the land through many centuries; has taken sides in internal strife and felt the tide of war surging round its gates; it has counted for so much in the life of England that one feels almost a sense of loss in finding it just a commonplace manufacturing town, with not a semblance of any of its former glory.

Like many other towns in England, it sprang up round a religious house—one of the string of important abbeys which stretched from Abingdon to Westminster. But before that it had been recognized as an important position.

We have seen that Oxford, Wallingford, and other places came into existence by reason of their important fords across the River. Reading arose into being because the long and narrow peninsula formed by the junction of the Kennet with the Thames was such a splendid spot for defensive purposes that right from early days there had been some sort of a stronghold there.

Here in this very safe place, then, the Conqueror’s son established his great foundation, the Cluniac Abbey of Reading, for the support of two hundred monks and for the refreshment of travellers. It was granted ample revenues, and given many valuable privileges, among them that of coining money. Its Abbot was a mitred Abbot, and had the right to sit with the lords spiritual in Parliament. From its very foundation it prospered, rising rapidly into a position of eminence; and, like the other abbeys, it did much towards the growth of the agricultural prosperity of the valley, encouraging the countryfolk to drain and cultivate their lands properly.

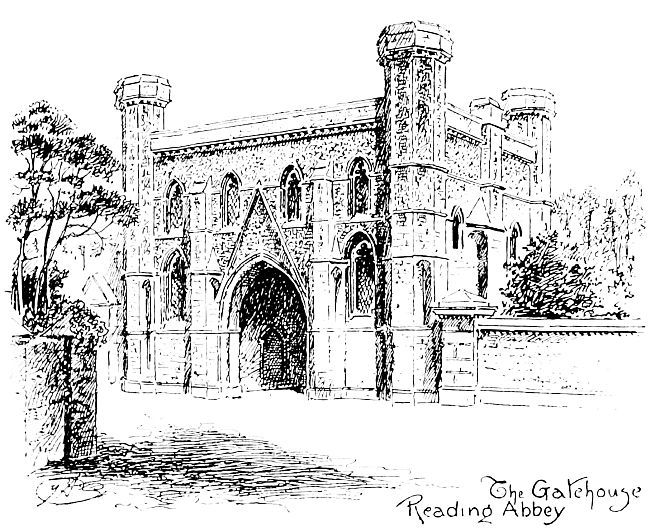

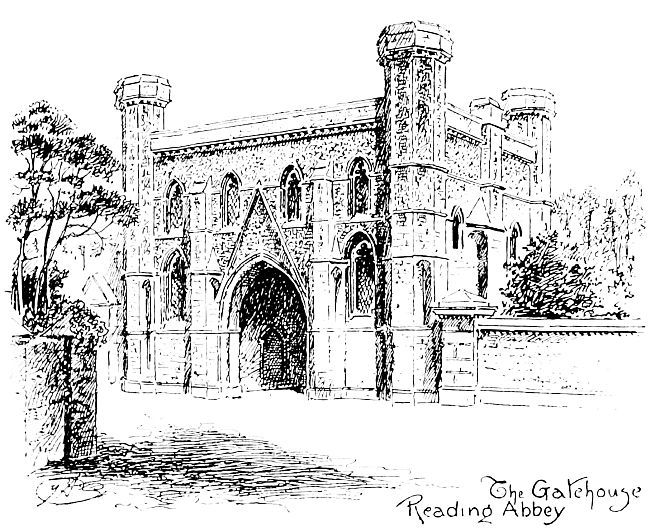

THE GATEHOUSE READING ABBEY

Though we first hear of it as a fortified place, and though at different times in history it felt the shock of war, Reading was never an important military centre, for the simple reason that it did not guard a main road across or beside the River. Consequently the interruptions in its steady progress were few and far between, and the place was left to develop its civilian and religious strength. This it did so well that during the four hundred years of the life of the Abbey it always counted for much with the Sovereigns, who went there to be entertained, and even in time of pestilence brought thither their parliaments, whose bodies were in the end buried there. By the thirteenth century the Abbey had risen to such a position that only Westminster could vie with it in wealth and magnificence.

And now what remains of it all? Almost nothing. There is what is called the old Abbey gateway, but it is merely a reconstruction with some of the ancient materials. In the Forbury Gardens lie all that is left, just one or two ivy-grown fragments of massive masonry, outlining perhaps the Chapter House, in which the parliaments were held, and the great Abbey Church, dedicated to St. Thomas Becket, where were the royal tombs and where in 1339 John of Gaunt was married. For the rest, the ruins have served all and sundry as a quarry for ready-prepared building stone during several centuries. Much of it was used to make St. Mary’s Church and the Hospital of the Poor Knights of Windsor; while still more was commandeered by General Conway for the construction of the bridge between Henley and Wargrave.

How did the Abbey come to such a state of dilapidation? Largely as a result of the Civil War. The Abbey was dissolved in 1539, and the Abbot actually hung, drawn, and quartered, because of his defiance. The royal tombs, where were buried Henry I., the Empress Maud, and others, were destroyed and the bones scattered; and from that time onwards things went from bad to worse. Henry VII. converted parts of it into a palace for himself and used it for a time, but in Elizabethan days it had got into such a very bad state that the Queen, who stayed there half-a-dozen times, gave permission for the rotting timbers and many cartloads of stone to be removed. But it remained a dwelling till the eventual destruction during the Rebellion.

During the war which proved so disastrous for the great Abbey, Reading was decidedly Royalist, but the fortunes of war brought several changes for it. It withstood for some time during 1643 a severe siege by the Earl of Essex, and, just as relief was at hand, it surrendered. Then Royalists and Parliamentarians in turn held the town; and naturally with these changes and the fighting involved the place suffered greatly, especially the outstanding building, the Abbey. St. Giles’ Church, which escaped destruction, still bears the marks of the bombardment.

But the town refused to die with the Abbey. The Abbey had done much to establish and vitalize the town. In its encouragement of the agriculture of the districts it had created the necessity for a central market-town, and Reading had grown and flourished accordingly. Thus, when the Abbey came to an end, the town was so firmly established that it was enabled to live on and prosper exceedingly.

Now Reading passes its days independent, almost unconscious, of the past, with its glory and its tragedy. Nor does the River any more enter into its calculations. To Reading has come the railway; and the railway has made the modern town what it is—an increasingly important manufacturing town and railway junction, and a ready centre for the rich agricultural land round about it; a hive of industry, with foundries, workshops, big commercial buildings, and a University College; with churches, chapels, picture-palaces, and fast-moving electric-tramcars, clanging their way along streets thronged with busy, hurrying people—in short, a typical, clean, modern industrial town, with nothing very attractive about it, but on the other hand nothing to repel or disgust.

Reading’s most famous industries are biscuit-making and seed-growing. Messrs. Huntley and Palmer’s biscuits, in the making of which four or five thousand people are employed, are known the world over; and so are Messrs. Sutton’s seeds, grown in, and advertised by, many acres of beautiful gardens.

The Kennet, on which the town really stands, is a river which has lost its ancient power, for the geologists tell us that along its valley the real mighty river once ran, receiving the considerable Cherwell-Thames tributary at this point. Now, whereas the tributary has grown in importance if not in size, the main stream has shrunk to such an enormous extent that the tributary has become the river, and the river the tributary. Of course, passing through Reading the little river loses its beauty, but the Kennet which comes down from the western end of the Marlborough Downs and flows through the Berkshire meadows is a delightful little stream.