CHAPTER THREE

Abingdon, Wallingford, and the Goring Gap

BETWEEN Oxford and Reading lies a land of shadows—a district dotted with towns which have shrunk to a mere vestige of their former greatness. To mention three names only—Abingdon, Dorchester, and Wallingford—is to conjure up a picture of departed glory.

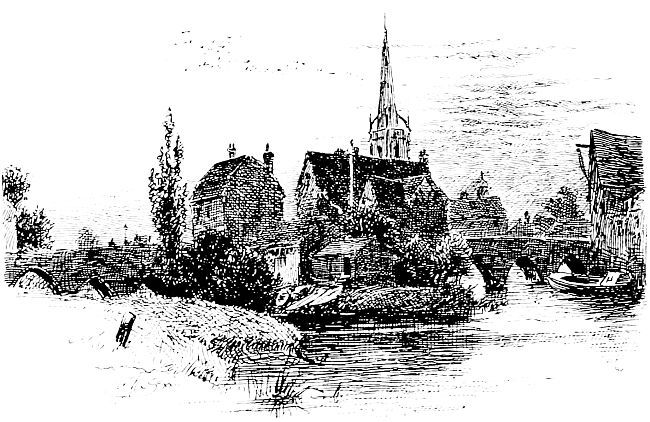

ABINGDON.

At Abingdon, centuries ago, was one of those great abbeys which stretched in a chain eastwards, and helped to ensure the prosperity of the valley; and the town sprang up and prospered, as was so often the case, under the shadow of the great ecclesiastical foundation. Unfortunately the monks and the citizens were constantly at loggerheads. The wealthy dwellers in the abbey, where the Conqueror’s own son, Henry Beauclerc, had been educated, and where the greatest in the land were wont to come, did not approve of tradesmen and other common folk congregating so near the sacred edifice. Thus in 1327 the proud mitred Abbot refused to allow the citizens to hold a market in the town, and a riot ensued, in which the folk of Abingdon were backed up by the Mayor of Oxford and a considerable crowd of the University students. A great part of the Abbey was burned down, many of its records were destroyed, and the monks were driven out. But the tradesmen’s triumph was short-lived, for the Abbot returned with powerful support, and certain of the ringleaders were hanged for their share in the disturbance.

However, the town grew despite the frowns of the Church, and it soon became a considerable centre for the cloth trade. Not only did it make cloth itself, but much of the traffic which there was between London and the western cloth-towns—Gloucester, Stroud, Cirencester, etc.—passed through Abingdon, particularly when its bridge had been built by John Huchyns and Geoffrey Barbur in 1416.

When, in 1538, the abbey was suppressed, the townsfolk rejoiced at the downfall of the rich and arrogant monks, and sought pleasure and revenge in the destruction of the former home of their enemies. So that in these days there is not a great deal remaining of the ancient fabric.

A few miles below Abingdon is Dorchester (not to be confused with the Dorset town of the same name), not exactly on the River, but about a mile up the tributary river, the Thame, which here comes wandering through the meadows to join the main stream. Like Abingdon, Dorchester has had its day, but its abbey church remains, built on the site of the ancient and extremely important Saxon cathedral; and, one must confess, it seems strangely out of place in such a sleepy little village.

Wallingford, even more than these, has lost its ancient prestige, for it was through several centuries a great stronghold and a royal residence. We have only to look at the map of the Thames Valley, and note how the various roads converge on this particularly useful ford, to see immediately Wallingford’s importance from a military and a commercial point of view. A powerful castle to guard such a valuable key to the midlands, or the south-west, was inevitable.

William the Conqueror, passing that way in order that he might discover a suitable crossing, and so get round to the north of London (p. 143), was shown the ford by one Wygod, the ruling thane of the district; and naturally William realized at once the possibilities of the place. A powerful castle soon arose in place of the old earthworks, and this castle lasted on till the Civil War, figuring frequently in the many struggles that occurred during the next three or four hundred years.

It played an important part in that prolonged and bitter struggle between Stephen and the Empress Maud, and suffered a very long siege. Again, in 1646, at the time of the Civil War, it was beset for sixty-five days by the Parliamentary armies; and, after a gallant stand by the Royalist garrison, was practically destroyed by Fairfax, who saw fit to blow it up. So that now very little stands: just a few crumbling walls and one window incorporated in the fabric of a private residence.

Between Wallingford and Reading lies what is, from the geographical point of view, one of the most interesting places in the whole length of the Thames Valley—Goring Gap.

You will see from a contour map that the Thames Basin, generally speaking, is a hill-encircled valley with gently undulating ground, except in the one place where the Marlborough-Chiltern range of chalk hills sweep right across the valley.

By the time the River reaches Goring Gap it has fallen from a height of about six hundred feet above sea-level to a height of about one hundred feet above sea-level; and there rises from the river on each side a steep slope four or five hundred feet high—Streatley Hill on the Berkshire side and Goring Heath on the Oxfordshire side.

The question arises, Why should these two ranges of hills, the Marlborough Downs and the Chiltern Hills, meet just at this point? Is it simply an accident of geography that their two ends stand exactly face to face on opposite sides of the Thames?

Now the geologists tell us that it is no coincidence. They have studied the strata—that is, the different layers of the materials forming the hills—and they find that the strata of the range on the Berkshire side compare exactly with the strata of the other; so that at some remote period the two must have been joined to form one unbroken range. How then did the gap come? Was it due to a cracking of the hill—a double crack with the earth slipping down in between, as has sometimes happened in the past? Here again the geologists tells us, No. Moreover they tell us that undoubtedly the River has cut its way right through the chalk hills.

“But how can that be possible?” someone says. “Here we have the Thames down in a low-lying plain on the north-west side of the hills, and down in the valley on the south-east side. How could a river flowing across a plain get up to the heights to commence the wearing away at the tops?” Here again the geologists must come to our aid. They tell us that back in that dim past, so interesting to picture yet so difficult to grasp, when the ancient, mighty River flowed (see Book I., Intro.), the chalk-lands extended from the Chilterns westwards, that there was no valley where now Oxford, Abingdon, and Lechlade lie, but that the River flowed across the top of a tableland of chalk from its sources in the higher grounds of the west to the brink at or near the eastern slope of the Chilterns; and that from this lofty position the River was able to wear its way down, and so make a V-shaped cutting in the end of the tableland. Afterwards there came an alteration in the surface. Some tremendous internal movement caused the land gradually to fold up, as it were; so that the tableland sagged down in the middle, leaving the Marlborough-Chiltern hills on the one side and the Cotswold-Edgehill range on the other, with the Oxford valley in between. But by this time the V-shaped gap had been cut sufficiently low to allow the River to flow through the hills, and to go on cutting its way still lower and lower.