CHAPTER EIGHT

Hampton Court

NEARLY twenty miles below Windsor we come upon the ancient palace of Hampton, better known in these days as Hampton Court, beautifully situated among tall trees not far from the river bank. It is a wonderful old place—one of the nation’s priceless possessions—and once inside we are loth to leave it, for there is something attractive about its quaint old courtyards and its restful, bird-haunted gardens.

Certainly it is the largest royal palace in England, and in some respects it is the finest. Yet, strangely enough, it was not built for a King, nor has any sovereign lived in it since the days of George II. Wolsey, the proud Cardinal of Henry VIII.’s days, erected it for his own private mansion, and it is still the Cardinal’s fabric which we look upon as we pass through the older portions of the great pile of buildings.

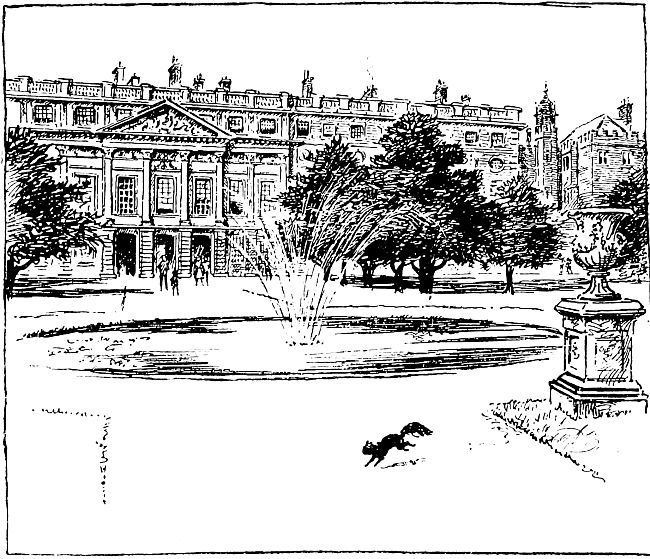

HAMPTON COURT, GARDEN FRONT.

Wolsey was, as you probably know, the son of a comparatively poor man, yet he was possessed of great gifts, and when he left Oxford he soon rose to a position of eminence. The Kings, first of all Henry VII., then “bluff King Hal,” showered honours and gifts on him. The Pope created him a Cardinal, and Henry VIII. gave him the powerful position of Lord Chancellor of England. Wolsey, as befitted his high station, lived a life of great splendour, the pomp and show of his household rivalling even that of the King. Naturally such a man would have the best, even of palaces.

As we pass through the wonderful old courts of the Cardinal’s dwelling we can imagine the vast amount of money which it must have cost to build, for it was magnificent in those days quite beyond parallel; and we cannot wonder that King Henry thought that such a building ought to be nothing less than a royal residence.

Little differences soon arose. Wolsey, indeed, had not lived long at Hampton Court when there came an open breach between the King and himself. The trouble increased, and he fell from his high place very rapidly. When in 1526 he presented Hampton Court Palace to the King something other than generosity must have prompted the gift.

Henry VIII. at once proceeded to make the palace more magnificent still. He pulled down the Cardinal’s banqueting hall and erected a more sumptuous one in its place; and this we can see to-day. Built in the style known to architects as Tudor, it is one of the finest halls in the whole of our land. Many huge beams of oak, beautifully fitted, carved, and ornamented, support a magnificent panelled and decorated roof, while glorious stained-glass windows (copies of the original ones fitted under Henry VIII.’s directions) fill the place with subdued light. The Great Gatehouse also belongs to Henry’s additions, and, with its octagonal towers and great pointed arch, has a very royal and imposing appearance.

Though no sovereign has dwelt in the palace for a century or more, it was for nearly two hundred years a favourite residence of our Kings and Queens, and many famous events have taken place within its walls. Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth were both very partial to the palace and its delightful gardens, and they spent much time there. Indeed, it is said that the latter was dining at Hampton when the glorious news of Drake’s defeat of the Spanish Armada was carried to her. James I. resided at the palace after his succession to the throne, and there, in addition to selling quite openly any number of knighthoods and peerages in order that he might add to his scanty means, he held the famous conference which decided that a uniform and authorized translation of the Bible should be made. In the great hall countless plays and masques were performed, and probably the mighty Shakespeare himself visited the place. King Charles I. spent many days at the Court, some of them as a prisoner of the Parliamentary soldiers; and here too Cromwell made a home until shortly before the time of his death. After the Restoration Charles II. and his Court settled at the palace, and in the surrounding parks indulged their fondness for the chase.

Immediately Mary and her husband, William of Orange, came to the throne they commenced the alterations which have largely given us the palace of to-day. The old State apartments were pulled down and, under the direction of Sir Christopher Wren, larger and more magnificent ones were erected, something on the lines of the famous French royal palace at Versailles. At the same time William ordered the grounds to be laid out in the style of the famous Dutch gardens. The next three sovereigns, Anne, and the first and second Georges, all lived at the Court; but from that time onwards it ceased to be a royal residence. George III. would not go near the place. The story is told that on one occasion at Hampton Court his grandfather boxed his ears soundly, and he vowed never again to live on the scene of such an indignity. At any rate, he divided up its thousand rooms into private suites of apartments, which were given as residences to persons of high social position whose incomes were not large enough to keep them. And to this day a very considerable portion of the palace is shut off from public view for the same purpose.

However, the parts which we can visit are extremely interesting. Entering at the main gate by Molesey Bridge, we cross the outer Green Court and come to the Moat. In Wolsey’s time this was crossed by a drawbridge of the sort in use when palaces were fortresses as well as dwelling-places. We now pass into the buildings over a fine old battlemented Tudor bridge.

This was built by Henry VIII. in honour of Anne Boleyn; but for centuries it lay buried and forgotten. Then one day, just before the War, workmen came upon it quite accidentally as they were cleaning out the old Moat.

Once through the gateway we come straight into the first of the old-world courtyards—the Base Court—and we feel almost as if we had stepped back several hundred years into a bygone age. The deep red brickwork of the battlements and the walls, the quaint chimneys, doorways, windows, and turrets, all belong to the distant past; they make on us an impression which not even the splendour of Wren’s additions can remove. Passing through another gateway—Anne Boleyn’s—we come into the Clock Court, so called because of the curious old timepiece above the archway. This clock was specially constructed for Henry VIII., and for centuries it has gone on telling the minute of the hour, the hour of the day, the day of the month, and the month of the year.

The Great Hall, which we may approach by a stairway leading up from Anne Boleyn’s Gateway is, as we have already said, a magnificent apartment. The glory of its elaborate roof can never be forgotten. Hanging on its walls are some very famous tapestries which have been at Hampton Court since the days of Henry VIII. Among these are “tenne pieces of new arras of the Historie of Abraham,” made in Brussels—some of the richest and most beautiful examples of the art of weaving ever produced. From the Great Hall we pass into what is known as the Watching Chamber or the Great Guard Room—the apartment in which the guards assembled when the monarch was at dinner, and through which passed all who desired audience of their sovereign. On its walls are wonderful old Flemish tapestries which once belonged to Wolsey himself. From the Watching Chamber we pass to another chamber through which the dishes were taken to the tables which stood on the dais at the end of the Hall.

Returning once more to the ground floor we go through a hall and find ourselves in Fountain Court. Here we enter another world entirely. Behind us are the quaint, old-fashioned courtyards, and the beautiful, restful Tudor buildings. The sudden change to Wren’s architecture has an effect almost startling. Yet when once we have forgotten the older buildings and become used to the very different style we see that Wren’s work has a beauty of its own. The newer buildings are very extensive, and the State apartments are filled with pictures and furniture of great interest. Entrance is obtained by what is called the King’s Great Staircase. The first room, entered by a fine doorway, is the Guard Room, a fine, lofty chamber with the upper part of its wall decorated with thousands of old weapons—guns, bayonets, pistols, swords, etc. From thence we pass to the round of the magnificent royal apartments—King’s rooms, Queen’s rooms, and so on, some thirty or more of them—all filled with priceless treasures—beautiful and rare paintings, delightful carvings from the master hand of Grinling Gibbons, so delicate and natural that it is difficult to believe they are made of wood, furniture of great historical interest and beauty. Here are the famous pictures—the “Triumph of Julius Cæsar,” nine large canvases showing the Roman emperor returning in triumph from one of his many wars. These were painted by Mantegna, the celebrated Italian artist, and originally formed part of the great collection brought together at Hampton Court by Charles I. They are a priceless possession. Here, too, are the famous “Hampton Court Beauties” and “Windsor Beauties,” the first painted by Sir Godfrey Kneller, the second by Sir Peter Lely, each portraying a number of famous beauties of the Court. Walking leisurely round these apartments we can obtain an excellent idea of the elaborate style of furnishing which was fashionable two or three centuries ago.

Yet, despite all these most valuable relics of the past, which many people come half across the world to view, for some folk the supreme attraction of Hampton Court will always be the gardens. Very beautiful they are too—the result of centuries of loving care by those, Kings and commoners, who had time and inclination to think of garden making. Perhaps to William of Orange must be given greatest credit in the matter, for it was he who ordered the setting-out of the long, shady avenues and alleys, and the velvety lawns and orderly paths. But we must not forget our debt of gratitude to Henry for the wonderful little sunken garden on the south side of the palace, perhaps one of the finest little old English gardens still in existence; and to Charles I. for the Canal, over a mile long, with its shady walk, and its birds and fishes, and its air of dreamy contentment.

Tens of thousands visit these grounds in the summer months, and the old grape-vine is always one of the chief attractions. Planted as long ago as 1768, it still flourishes and bears an abundant crop each year, sometimes as many as 2,500 bunches, all of fine quality. Its main stem is now over four feet in circumference, and its longest branch about one hundred and twenty feet in length. On the east front, stretching in one unbroken line across the Home Park for three-quarters of a mile towards Kingston, is the Long Water, an ornamental lake made by Charles II. North of the buildings is another garden, known as the Wilderness, and here we may find the celebrated Maze, constructed in the time of William and Mary. This consists of a great number of winding and zig-zag paths, hedged on each side with yew and other shrubs; and the puzzle is to find the way into the little open space in the centre. On almost any day in the summer can be heard the merry laughter of visitors who have lost their way in the labyrinth of paths.

Still farther north lies Bushey Park, with its famous Chestnut Avenue, stretching over a mile in the direction of Teddington. Here are more than a thousand acres of the finest English parkland; and this, together with the large riverside stretch known as the Home Park, formed the royal demesne in which the monarchs and their followers hunted the deer.

As was said at the beginning of the chapter, only with reluctance do we leave Hampton Court, partly because of its very great beauty, partly because of its enthralling historical associations. As we turn our backs on the great Chancellor’s memorial, we think perhaps a trifle sadly of all that the place must have meant to Wolsey, and there come to mind those resounding words which Shakespeare put into his mouth—“Farewell, a long farewell, to all my greatness.”