CHAPTER NINE

Kingston

ALREADY we have seen that in many cases, if not in most, the River has founded the towns on its banks. These have sprung up originally to guard either an important crossing or the junction of a tributary with the main stream or a “gate” where the River has found a way through the hills; and then, outliving the period of their military usefulness, they have developed later into centres of some commercial importance. Thus it has been with Kingston-upon-Thames, a place of ancient fame, for, according to the geology of the district, there must have been at this spot one of the lowest fords of the River.

That there was on Kingston Hill a Roman station guarding that ford there can be very little doubt; and there are evidences that a considerable Roman town was situated here, for the Roman remains brought to light have been fairly abundant.

Workmen digging or ploughing on the hillside up towards Coombe Warren have, at various times in the past, discovered the foundations of Roman villas, with gold, silver, and bronze coins of the fourth century, and numerous household goods, and in one place a cemetery full of funeral urns.

But it was not till Saxon times that Kingston came to the heyday of its existence. Then it was a place of the greatest possible importance, for here England was united into one country under one King. Prior to the union England was divided off into a number of states, which found amusement in fighting each other when they were not fighting the ancient Britons in their western fastnesses. These states were Northumbria, in the north; Mercia in the Midlands; Wessex in the south-west; and, in addition, the smaller areas of East Anglia, Essex, and Kent. When any one chieftain or king was sufficiently strong to defeat the others, and make them do his will, he became for the time being the “bretwalda,” or overlord; but it was a very precarious honour. The kings in turn won the distinction, but the greater ones emerged from the struggle, and in the end Egbert, king of Wessex, by subduing the Mercians, became so powerful that all the other kings submitted to him. Thus Egbert became the first king or overlord of all the English (827), and picked on Kingston as the place for his great council or witenagemot.

Then followed the terrible years of the Danish invasions, and England was once more split up into sections; but the trouble passed, and Edward the Elder, elected and crowned king of Wessex at Kingston, eventually became the real King of England, the first to be addressed in those terms by the Pope of Rome.

Thence onward Kingston was the recognized place of coronation for the English Kings, till Edward the Confessor allotted that distinction to his new Abbey at Westminster. In addition, it was one of the royal residences and the home of the Bishops of Winchester, whose palace was situated where now a narrow street, called Bishop’s Hall, runs down from Thames Street to the River. So that Kingston’s position as one of the chief towns of Wessex was acknowledged.

The stone on which the Saxon Kings were crowned stands now quite close to the market-place, jealously guarded by proper railings, as such a treasure should be. Originally it was housed in a little chapel, called the Chapel of St. Mary, close to the Parish Church, and with it were preserved effigies of the sovereigns crowned; but unfortunately in the year 1730 the chapel collapsed, killing the foolish sexton who had been digging too close to the foundations. Then for years the stone was left out in the market-place, unhonoured and almost unrecognized, till in the year 1850 it was rescued and mounted in its present position. According to the inscription round the base, the English Kings crowned at Kingston included Edward the Elder (902), Athelstan (924), Edmund I. (940), Edred (946), Edwy the Fair (955), Edward the Martyr (975), and Ethelred II. (979).

That most wretched of monarchs, King John, gave the town its first charter, and for a time at least resided here. In the High Street there is now shown a quaint old building to which the title of “King John’s Dairy” has been given, and this possibly marks the situation of the King’s dwelling-place.

There was a castle here from quite early days, for we read that in 1263, when Henry III. was fighting against his barons, Kingston Castle fell into the hands of de Montfort’s colleagues, who captured and held the young Prince Edward; and that Henry returned in the following year and won the castle back again. At the spot where Eden Street joins the London Road were found the remains of walls of great thickness, and these, which are still to be seen in the cellars of houses there, are commonly supposed to be the foundations of a castle held by the Earls of Warwick at the time of the Wars of the Roses, and possibly of an even earlier structure.

Right down through history Kingston, probably by reason of its important river crossing, has had its peaceful life disturbed at intervals by the various national struggles. Armies have descended on it suddenly, stayed the night, taken their fill, and gone on their way; a few have come and stayed. Monarchs have broken their journeys at this convenient spot, or have dined here in state to show their favour. For Kingston, as the King’s “tun” or town should, has always been a distinctly Royalist town, has invariably declared for the sovereign—right or wrong.

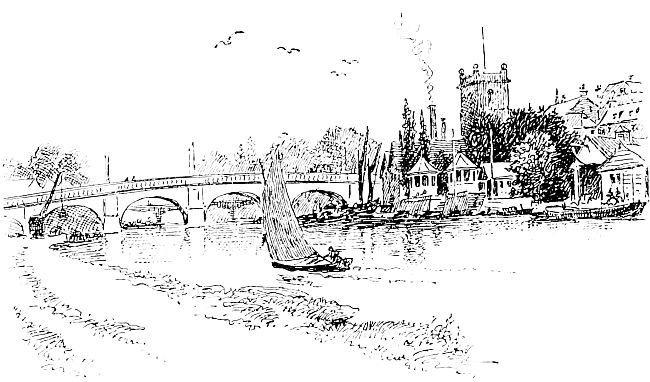

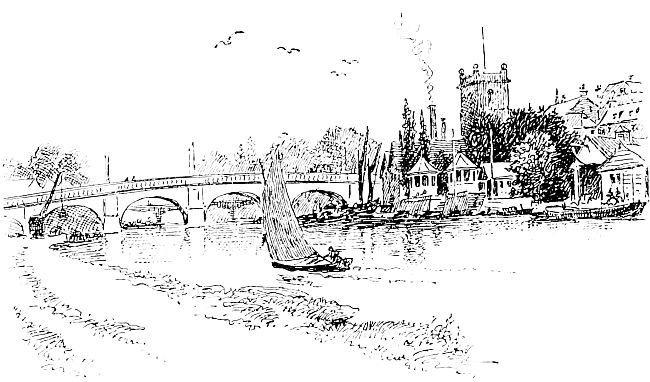

KINGSTON.

Thus in 1554, when young Sir Thomas Wyatt raised his army of ten thousand to attack London, and found the Bridge too strong to force, he made his way westwards to the convenient crossing at Kingston; but the inhabitants broke down their bridge to delay his progress, and so enabled Mary to get together a force; for which act of devotion the citizens were rewarded with a free charter by Queen Mary.

Similarly, in the Civil War the town stood firmly by Charles, despite the fact that the town was occupied by cavaliers and roundheads in turn. Thus in October, 1642, the Earl of Essex settled down with several thousand men; while in November Sir Richard Onslow came to defend the crossing. But the inhabitants showed themselves extremely “malignant”; though when, just after, the King came to the town with his army he was greeted with every sign of joyous welcome.

Also at Kingston occurred one of the numerous risings which happened during the year 1648. All over the land the Royalists gathered men and raised the King’s standard, hoping that Parliament would not be able to cope with so many simultaneous insurrections. In July the Earl of Holland, High Steward of Kingston, the Duke of Buckingham, and his brother Lord Francis Villiers, got together a force of several hundred horsemen, but they were heavily defeated by a force of Parliamentarians, and Lord Villiers was killed.

TEDDINGTON WEIR

Nowadays, despite the fact that the town has held its own through a thousand years, neither losing in fame a great deal nor gaining, Kingston does not give one any impression of age. True, it has some ancient dwellings here and there, but for the most part they are hidden away behind unsightly commercial frontages.

Between Kingston and Richmond the River sweeps round in an inverted S-bend, passing on the way Teddington and Twickenham, formerly two very pretty riverside villages. The former possess the lowest pound-lock on the River (with the exception of that of the half-tide lock at Richmond), and also a considerable weir. It is the point at which the tide reaches its limit, and thereby gets its name Teddington, or Tide-ending-town.