CHAPTER ELEVEN

Richmond to Westminster

JUST below Richmond, on the borders of the Middlesex village of Isleworth, there is a foot-passenger toll-bridge, with what is known as a half-tide lock. The arches of this bridge are open to river traffic during the first half of the ebb-tide and the second half of the flow, but the River is dammed for the remainder of the day in order that sufficient water may be kept in the stretch immediately above. This, for the present, is the last obstruction on the journey seawards.

Isleworth, with its riverside church, its ancient inn, “The London Apprentice,” and its great flour-mill, is a typical riverside village which has lived on out of the past. Between it and Brentford lies the magnificent seat of the Dukes of Northumberland—Sion House—a fine dwelling situated in a delightful expanse of parkland facing Kew Gardens on the Surrey shore.

Of Kew Gardens, which stretch beside the River from the Old Deer Park almost to Kew Bridge, it is difficult for one who loves nature to speak in moderate terms, for it is one of the most delightful places in the whole of our land. At every season of the year, almost every day, there is some fresh enchantment, some glory of tree or flower unfolding itself, so that one can go there year after year, week in and week out, without exhausting its treasure-house of wonders, even though there is only a matter of 350 acres to explore.

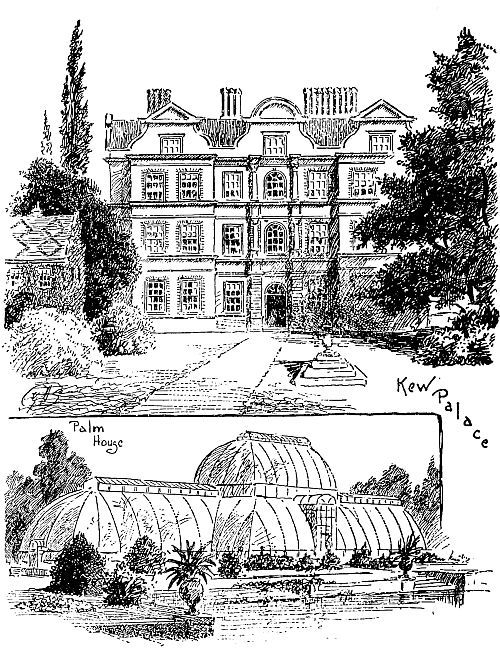

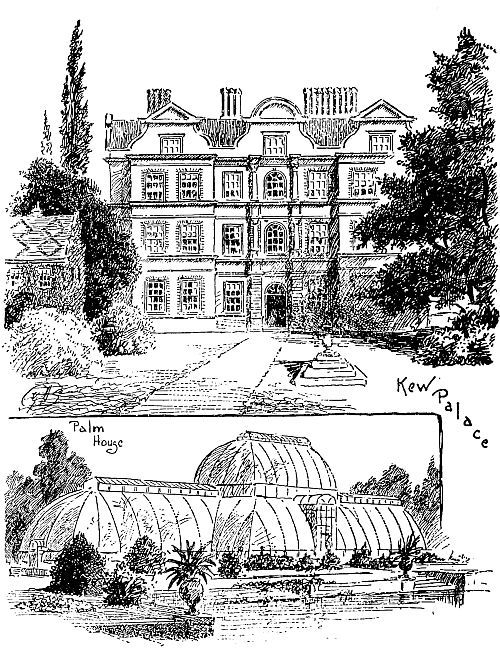

KEW PALACE AND KEW GARDENS.

The Royal Botanical Gardens, as their proper name is, were first laid out by George III. in the year 1760, and were presented to the nation by Queen Victoria in the year 1840. Since then the authorities have planned and worked assiduously and wisely to bring together a botanical collection of such scope and admirable arrangement that it is practically without rival in the world. Here may be seen, flourishing in various huge glasshouses, the most beautiful of tropical and semi-tropical plants—palms, ferns, cacti, orchids, giant lilies, etc.; while in the magnificently laid out grounds are to be found flowers, trees, and shrubs of all kinds growing in a delightful profusion. There is not a dull spot anywhere; while the rhododendron dell, the azalea garden, the rock garden, and the rose walks are indescribably beautiful. Nor is beauty the only consideration, for the carefully planned gardens, with their splendid museum, are of untold value to the gardener and the botanist.

Nor must we forget that Kew had its palace. Frederick, Prince of Wales, father of George III. and great patron of Surrey cricket, resided at Kew House, as did his son after him. The son pulled down the mansion in 1803 and erected another in its place; and, not to be outdone, George IV. in turn demolished this. The smaller dwelling-house—dignified now by the title of palace—a homely red-brick building, known in Queen Anne’s time as the “Dutch House,” was built in the reign of James I. In it died Queen Charlotte.

If we speak with unstinting praise of Kew, what shall we say of Brentford, opposite it on the Middlesex side of the stream? Surely no county in England has a more untidy and squalid little county town. Its long main street is narrow to the point of danger, so that it has been necessary to construct at great cost a new arterial road which will avoid Brentford altogether; while many of its byways can be dignified by no better word than slums. Yet Brentford in the past was a place of some note in Middlesex, and had its share of history. Indeed, in recent times it has laid claim to be the “ford” where Julius Cæsar crossed on his way to Verulam, a claim which for years was held undisputedly by Cowey Stakes, near Walton.

Now the Great Western Railway Company’s extensive docks, where numerous barges discharge and receive their cargoes, and the incidental sidings and warehouses, the gas-works, the various factories and commercial buildings, make riverside Brentford a thing of positive ugliness.

On the bank above the ferry, close to the spot where the little Brent River joins the main stream, the inhabitants, proud of their share in the nation’s struggles, have erected a granite pillar with the following brief recital of the town’s claims to notoriety:

54 B.C.—At this ancient fortified ford the British tribesmen, under Cassivelaunus, bravely opposed Julius Cæsar on his march to Verulamium.

A.D. 780-1.—Near by Offa, King of Mercia, with his Queen, the bishops, and principal officers, held a Council of the Church.

A.D. 1016.—Here Edmund Ironside, King of England, drove Cnut and his defeated Danes across the Thames.

A.D. 1640.—Close by was fought the Battle of Brentford between the forces of King Charles I. and the Parliament.

From Kew Bridge onwards the River loses steadily in charm if it gains somewhat in importance. The beauty which has clung to it practically all the way from the Cotswolds now almost entirely disappears, giving place to a generally depressing aspect, relieved here and there with just faint suggestions of the receding charm.

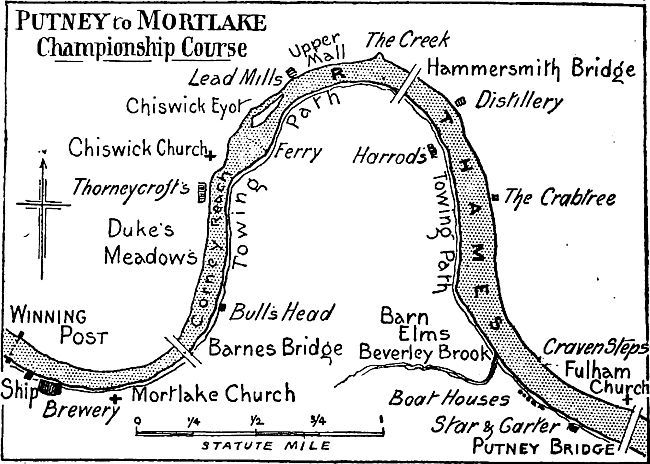

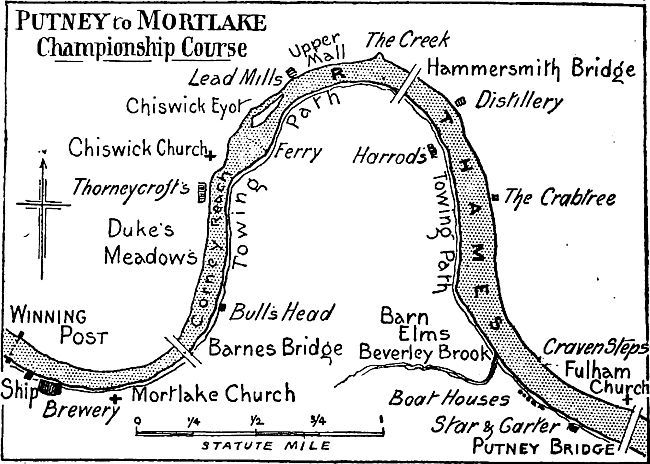

A short distance downstream is Mortlake, once a pretty little riverside village, now almost a suburb of London, and quite uninteresting save that it marks the finish of the University Boatrace. This, as all folk in the Thames Valley (and many out of it) are aware, is rowed each year upstream from Putney to Mortlake, usually on the flood-tide.

PUTNEY to MORTLAKE Championship Course

Barnes, on the Surrey shore, is a very ancient place. The Manor of Barn Elmes was presented by Athelstan (925-940) to the canons of St. Paul’s, and by them it has been held ever since. The name possibly came from the great barn or spicarium, which the canons had on the spot. The place is now the home of the Ranelagh Club—a famous club for outdoor pursuits, notably polo, golf, and tennis.

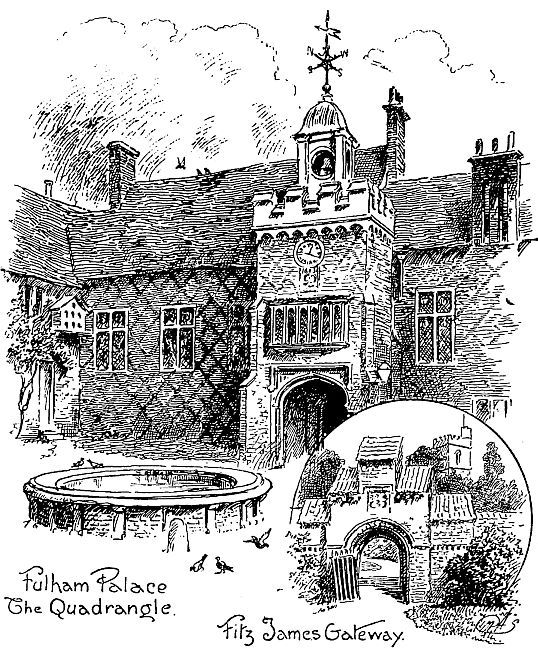

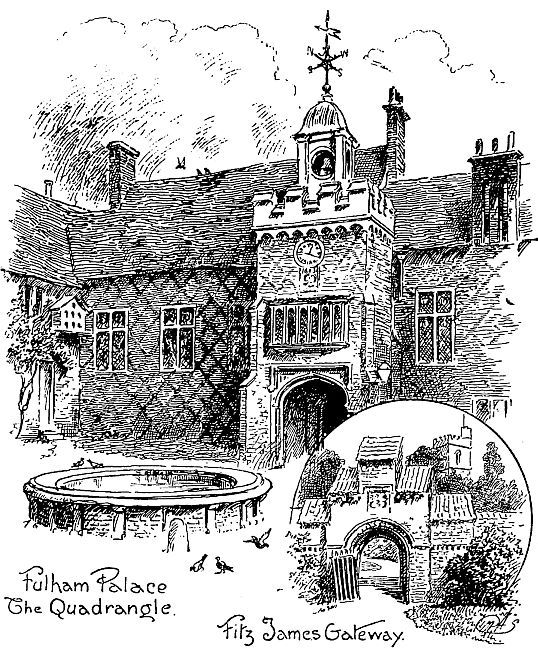

Fulham Palace, on the Middlesex bank, not far from Putney Bridge, is the “country residence” of the Bishops of London. For nine centuries the Bishops have held the manor of Fulham, and during most of the time have had their domicile in the village. In these days, when Fulham is one of the utterly dreary districts of London, with acres and acres of dull, commonplace streets, it is hard indeed to think of it as a fresh riverside village with fine old mansions and a wide expanse of market-gardens and a moat-surrounded palace hidden among the tall trees.

Fulham Palace The Quadrangle

Fitz James Gateway.

The River now begins to run through London proper, and from its banks rise wharves, warehouses, factories, and numerous other indications of its manifold commercial activities. Thus it continues on past Wandsworth, where the tiny river Wandle joins forces and where there is talk of erecting another half-tide lock, past Fulham, Chelsea, Battersea, Pimlico, Vauxhall, and Lambeth, on to Westminster.

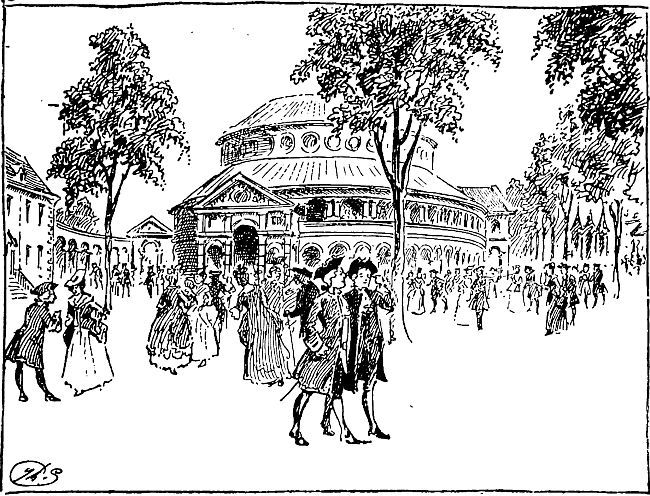

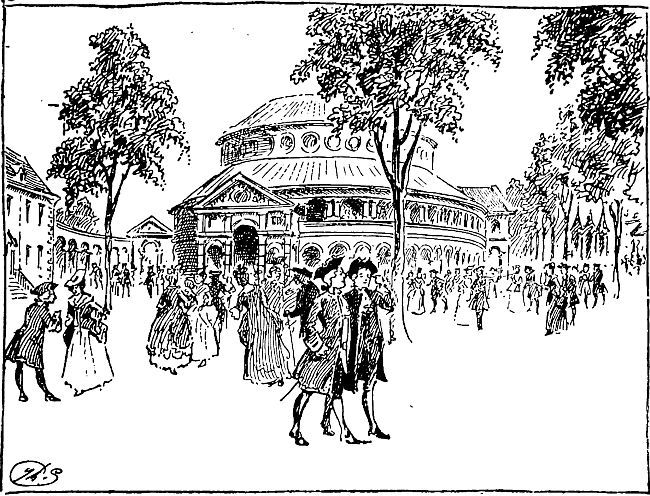

RANELAGH.

At Chelsea and Vauxhall were situated those famous pleasure-gardens—the Ranelagh and Cremorne Gardens at the former, and the Spring Gardens at the latter—which during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries provided London with so much in the way of entertainment. Vauxhall Gardens were opened to the public some time after the Restoration, and at once became popular, so that folk of all sorts, rich and poor alike, came to pass a pleasant evening. An account written in 1751 speaks of the gardens as “laid out in so grand a taste that they are frequented in the three summer months by most of the nobility and gentry then in or near London.” The following passage from Smollett’s “Humphrey Clinker” aptly describes the dazzling scene: “A spacious garden, part laid out in delightful walks, bounded with high hedges and trees, and paved with gravel; part exhibiting a wonderful assemblage of the most picturesque and striking objects, pavilions, lodges, graves, grottos, lawns, temples, and cascades; porticoes, colonnades, rotundas; adorned with pillars, statues, and paintings; the whole illuminated with an infinite number of lamps, disposed in different figures of suns, stars, and constellations; the place crowded with the gayest company, ranging through those blissful shades, and supping in different lodges on cold collations, enlivened with mirth, freedom, and good humour, and animated by an excellent band of music.”

In the early days most of the folk came by water, and the river was gay with boatloads of revellers Barges and boats waited each evening at Westminster and Whitehall Stairs in readiness for passengers; and similarly at various places along the city front craft plied for hire to convey the citizens, their wives and daughters, and even their apprentices.

Ranelagh was not quite so ancient, and it encouraged a slightly better class of visitor: otherwise it was the counterpart of Vauxhall, as was Cremorne. It was famous, among other things, for its regatta. In 1775 this was a tremendous water-carnival. The River from London Bridge westwards was covered with boats of all sorts, and stands were erected on the banks for the convenience of spectators.

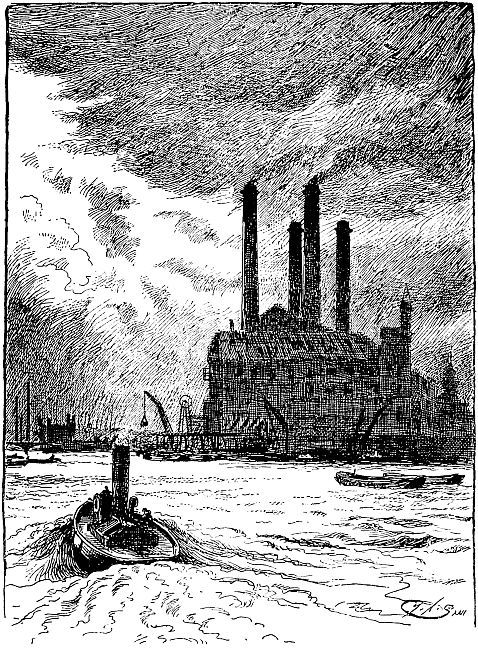

Ranelagh was demolished in 1805, but Vauxhall persisted right on till 1859, when it too came under the auctioneer’s hammer. Where Cremorne once stood is now the huge power-station so prominent in this stretch of the river; and the famous coffee-house kept by “Don Saltero” in the early eighteenth century was in Cheyne Walk.

Chelsea in its day has achieved fame in quite a variety of ways. Apart from its pleasure gardens it has come to be well-known for its beautiful old physic-garden; its hospital for aged soldiers, part of the gardens of which were included in Ranelagh; its bun-house; its pottery; and last, but by no means least, for its association with literary celebrities. Here have lived, and worked, and, in some cases, died, writers of such different types as Sir Thomas More, whose headless body was buried in the church, John Locke, Addison, Swift, Smollett, Carlyle—the “sage of Chelsea”—Leigh Hunt, Rossetti, Swinburne, and Kingsley. Artists, too, have congregated in these quiet streets, and the names of Turner and Whistler will never be forgotten.

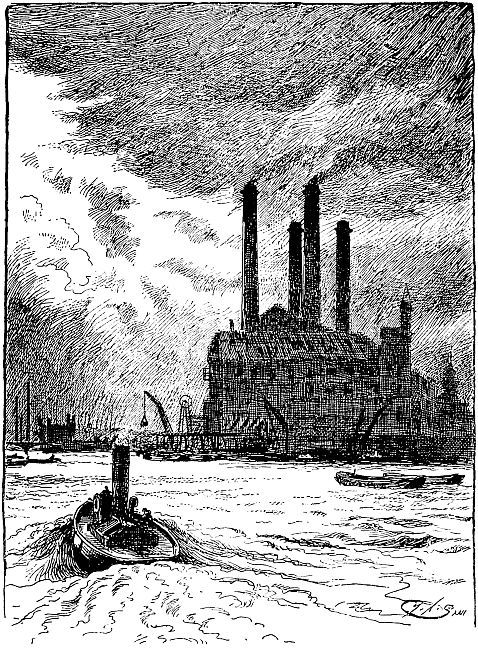

THE POWER-STATION, CHELSEA.

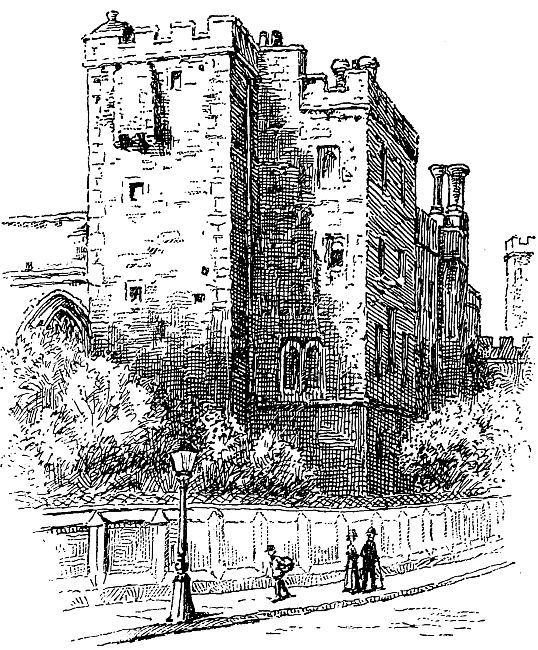

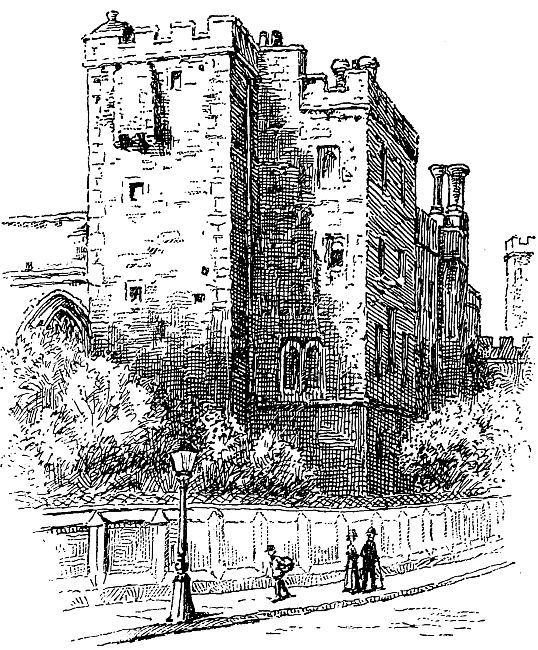

At Lambeth may still be seen the famous palace of the Archbishops of Canterbury, a beautiful building of red-brick and stone, standing in an old-world garden. Some parts of it are very old: one, the Lollards’ Tower, is an exceedingly fine relic of medieval building. Close at hand stands the huge pile of buildings which house the pottery works of Messrs. Doulton. For some reason or other Lambeth has long been associated with this industry.

THE LOLLARDS’ TOWER, LAMBETH PALACE.

As early as 1670 one Edward Warner sold potters’ clay here, and exported it in huge quantities to Holland and other countries, and various potters, some Dutch, settled in the district. All this stretch of the River seems to have been famous for its china-works in the past, for there were celebrated potteries at Fulham, Chelsea, and Battersea as well. Of these Battersea has passed away, and its productions are eagerly sought after by collectors, but Fulham and Lambeth remain, while Chelsea, after a long interval, is reviving this ancient craft.

Thus we have traversed in fancy the whole of this wonderful River—so fascinating to both young and old, to both studious and pleasure-seeking. The more we learn of it the more we are enthralled by its story, by the immense share it has had in the shaping of England’s destinies.

We started with a consideration of what those wonderful people the geologists could tell us of the River in dim, prehistoric days; and we feel inclined to turn once more to them in conclusion. For they tell us now that the Thames is growing less; that, just as in times past it captured the waters of other streams and reduced them to trickling nothings, so in turn it is succumbing day by day to the depredations of the River Ouse, which is slowly cutting off its head. Some day, perhaps, the Thames will be just a tiny rivulet, and the Port of London will be no more; but I think the tides will ebb and flow under London Bridge many times before it comes to pass.