CHAPTER TEN

Richmond

RICHMOND is an old place with a new name, for though its history goes back to Saxon times, it did not get its present name till the reign of Henry VII., when “Harry of Richmond” rechristened it in allusion to the title which he received from the Yorkshire town. Prior to that it had always been called Sheen, and the name still survives in an outlying part of the town.

Sheen Manor House had been right from Saxon days a hunting lodge and an occasional dwelling for the Sovereigns, but Edward III. built a substantial palace, and, absolutely deserted by all his friends, died in it in the year 1377. He was succeeded by his young grandson, the Black Prince’s child Richard, who spent most of his childhood with his mother Joan at Kingston Castle, just a mile or two higher upstream. Richard’s wife, Queen Anne of Bohemia, died in Sheen Palace in the year 1394, and Richard was so upset that he had the palace pulled down, and never visited Sheen again.

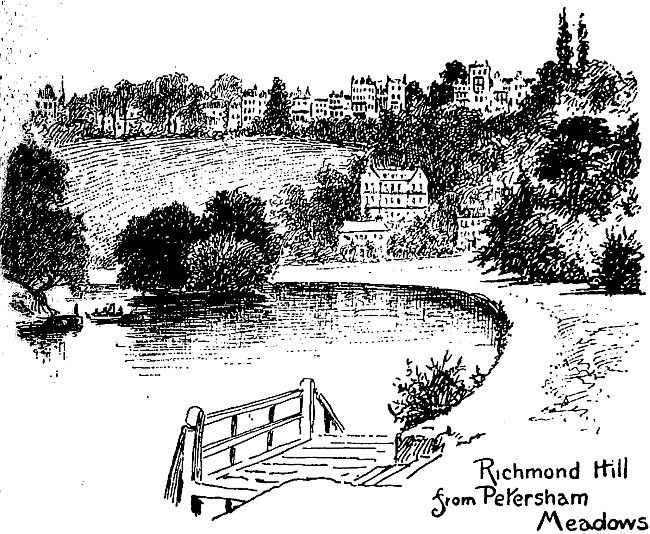

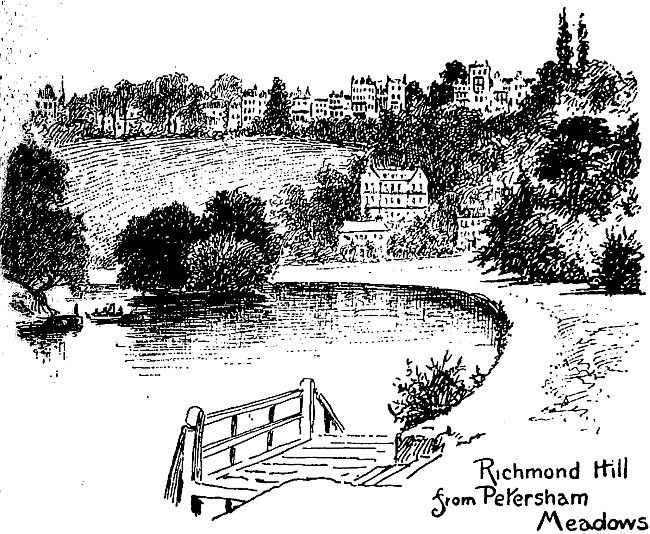

RICHMOND HILL FROM PETERSHAM MEADOWS

This, however, by no means ended the life of Sheen as a royal residence, for Henry V. built a new house, and when, in 1498, this was burned down, Henry VII. built a new palace on a much grander scale, and at the same time gave it the name which it still bears. With the Tudor kings and queens Richmond was a very great favourite. “Bluff King Hal” loved to hunt in its woodland, and here, in 1603, “good Queen Bess” died, after forty-five years of a troublous but prosperous and progressive reign. Charles I. spent much of his time here, and he it was who added Richmond Park to the royal domain in the year 1637.

After the Civil War the palace was set aside for the use of the widowed Queen Henrietta Maria, but by that time it had got into a very dilapidated condition; and little or nothing was done to improve it. So that before long this once stately palace fell to pieces and was removed piecemeal. Now all that remains of it is a gateway by Richmond Green.

Richmond to-day is merely a suburb of London, one of the pleasure grounds of the city’s countless workers, who come hither on Saturdays and Sundays either to find exercise and enjoyment on the River, or to breathe the pure air of the park. This New Park, so called to distinguish it from the Old Deer Park, which lies at the other end of the town, is a very fine place indeed. Surrounded by a wall about eleven miles long, it covers 2,250 acres of splendid park and woodland, with glorious views in all directions. In it are to be found numerous deer which spend their young days here, and later are transferred to Windsor Park. The Old Deer Park, of which about a hundred acres are open to the public for football, golf, tennis, and other pastimes, lies by the riverside between the town and Kew Gardens.

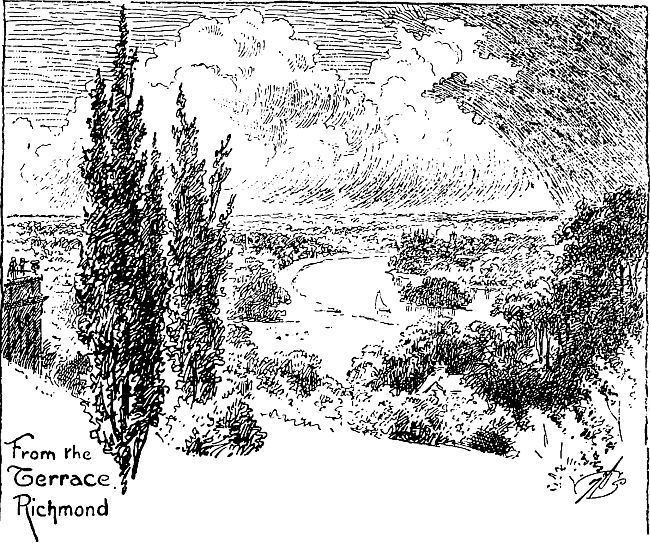

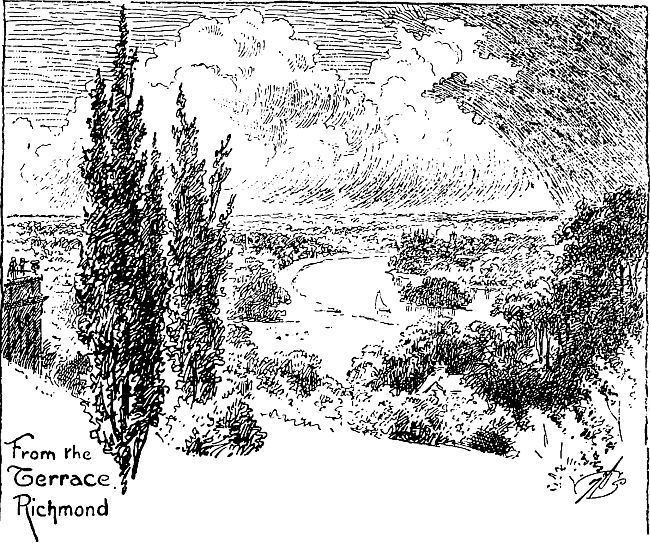

FROM THE TERRACE RICHMOND

The view of the River Thames from the Terrace on Richmond Hill is world-famous. Countless artists have painted it, and many writers have described it; and probably it has deserved all the good things said about it, for even now, spoiled as it is by odd factory chimneys and unsightly buildings dotted about, it still remains one of the most delightful vistas of the silvery, winding River. Those of you who have read Scott’s “Heart of Midlothian” will probably remember the passage (chapter xxxvi.) which describes it: “The equipage stopped on a commanding eminence, where the beauty of English landscape was displayed in its utmost luxuriance. Here the Duke alighted and desired Jeanie to follow him. They paused for a moment on the brow of a hill, to gaze on the unrivalled landscape which it presented. A huge sea of verdure, with crossing and intersecting promontories of massive and tufted groves, was tenanted by numberless flocks and herds, which seemed to wander unrestrained and unbounded through the rich pastures. The Thames, here turreted with villas and there garlanded with forests, moved on slowly and placidly, like the mighty monarch of the scene, to whom all its other beauties were but accessories, and bore on its bosom a hundred barks and skiffs, whose white sails and gaily fluttering pennons gave life to the whole. The Duke was, of course, familiar with this scene; but to a man of taste it must be always new.”

Nor have the poets been behindhand with their appreciation, as the following extract from James Thomson’s “Seasons” shows:

“Heavens! what a goodly prospect spreads around,

Of hills, and dales, and woods, and lawns, and spires,

And glittering towers, and gilded streams, till all

The stretching landscape into smoke decays.”