But far more important were broader issues that the

increasingly tolerant and cosmopolitan mid-20th

Gideon decision had raised. If the Sixth Amendment’s

century, that state-enforced racial segregation violated

74

the Constitution?

judges – particularly nominees to sit on the Supreme

But critics of the “living document” approach argue

Court – a dispute that shows no sign of ending.

that this is an invitation to activist judges to write their

After his acquittal, Clarence Earl Gideon drifted

own notions of desirable social policy into the Constitu-

from one Florida tavern to the next until January 18,

tion. The critics often cite, as an example of this, the

1972, when he died at the age of 6l. That same year, the

Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade, the 1973 deci-

Supreme Court expanded its ruling in his case to require

sion that established a constitutional right for women

counsel for any defendant who, if convicted, might

to obtain abortions. The Court’s opinion held that

spend even one day in jail.

laws forbidding abortions violated the privacy rights of

Gideon was initially buried in an unmarked grave.

women and their physicians to make decisions involving

Donors later provided a headstone with this inscription:

abortions without interference from the state. The crit-

“Each era fi nds an improvement in law for the benefi t

ics point out that the Constitution and the Bill of Rights

of mankind.”

say nothing about privacy rights, and they allege that the

justices concocted an implied right of privacy in order to

arrive at a result they considered desirable.

Fred Graham has been a legal journalist since becoming Supreme Court cor-This constitutional debate has evolved into a heated

respondent for The New York Times in 1965. In 1972, he switched media, political struggle. Liberals, for the most part, favor the

becoming law correspondent for CBS Television News, and in 1989 was hired

“living Constitution” approach, while conservatives

by the then-new television legal network, Court TV, to be its chief anchor and argue that judges should leave lawmaking to the

managing editor. He is now Court TV’s senior editor, stationed in Washington, legislatures. One result has been an ongoing political

D.C. Mr. Graham has a law degree from Vanderbilt University and a Diploma dispute over the appointment and confi rmation of

in Law as a Fulbright Scholar at Oxford University.

75

Immigration laws have affected the social, political, and economic

development of the United States, a nation of

immigrants since the 17th century – and earlier. Changes made to

law in the 1960s have resulted in a more diverse nation.

Below and left, new citizens take the oath of allegiance to the United States.

Facing page: President Lyndon B. Johnson at the signing ceremony for the Immigration Act of 1965.

76

by Roger Daniels

The Immigration Act of 1965:

Intended and Unintended Consequences

WHEN LYNDON JOHNSON SIGNED THE IMMIGRATION ACT

OF 1965 AT THE FOOT OF THE STATUE OF LIBERTY ON

OCTOBER 3 OF THAT YEAR, HE STRESSED THE LAW’S

SYMBOLIC IMPORTANCE OVER ALL:

THIS BILL THAT WE WILL SIGN TODAY IS NOT

A REVOLUTIONARY BILL. IT DOES NOT

AFFECT THE LIVES OF MILLIONS. IT WILL NOT

RESHAPE THE STRUCTURE OF OUR DAILY

LIVES, OR REALLY ADD IMPORTANTLY TO

EITHER OUR WEALTH OR OUR POWER. YET

IT IS STILL ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT

ACTS OF THIS CONGRESS AND OF THIS

ADMINISTRATION [AS IT] CORRECTS A CRUEL

AND ENDURING WRONG IN THE CONDUCT OF

THE AMERICAN NATION.

THE PRESIDENT FROM TEXAS WAS NOT BEING UNCHARAC-

TERISTICALLY MODEST. JOHNSON WAS SAYING WHAT HIS

ADVISORS AND “EXPERTS” HAD TOLD HIM. LITTLE NOTED

77

at the time and ignored by most historians for decades,

– continued to grow throughout the final two decades of

the 1965 law is now regarded as one of three 1965

the 19th century and the first two of the 20th.

statutes that denote the high-water mark of late 20th-

Perhaps because of the influx, anti-immigrant senti-

century American liberalism. (The other two are the

ment among nativists heightened when a sharp post-

Voting Rights Act, which enforced the right of African

World War I economic downturn combined with fears

Americans to vote, and the Medicare/Medicaid Act,

about the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and left-wing

which financed health care for older Americans and for

domestic radicalism resulted in a panic about a largely

persons in poverty.) The Immigration Act was chiefly

imaginary flood of European immigration. The chairman

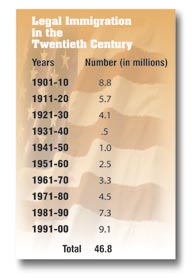

responsible for the tremendous surge in immigration in

of the immigration committee of the House of Represen-

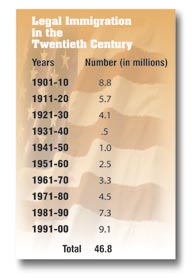

the last third of the 20th century (as Table I on page 80

tatives, Albert Johnson, a Republican representing a rural

shows) and also greatly heightened the growing

district in Washington state, used excerpts from consular

incidence of Latin Americans and Asians in the mix of

reports to argue that the country was in danger of being

arrivals to the United States in the decades that followed.

swamped by “abnormally twisted” and “unassimilable”

Why did the president’s experts so markedly misjudge

Jews, “filthy, un-American and often dangerous in their

the myriad potential consequences of the new law?

habits.” While those views were extreme for the time,

Because they focused on old

the consensus of Congress was

battles while failing to analyze

that too many Southern and

the actual changes which had al-

Eastern Europeans, predomi-

ready occurred by that date. In-

nantly Catholics and Jews, were

deed, to understand the nature

coming into the country – and

of the changes wrought and who

this view was clearly shared

was able to come to America as a

by many if not most Ameri-

result of the new law, it is neces-

cans in those days. Spurred by

sary to examine the prior course

such distaste, if not alarm, in

of American immigration policy.

the 1920-21 winter session of

Congress, the House of Repre-

American

sentatives voted 293-46 in favor

of a 14-month suspension of all

Immigration

immigration.

The somewhat less alarm-

Policy Before

ist Senate rejected the notion

of zero immigration and sub-

1921

stituted a bill sponsored by

Senator William P. Dillingham,

a Vermont Republican. His

plan was agreed to by Congress

Prior to 1882, there were no This 1921 political cartoon criticizes the U.S. government for trying to but was vetoed by the outgo-significant restrictions on

limit immigration (in those days mostly from Europe).

ing president, Woodrow Wilson.

any group of free immigrants who wanted to settle in the

The new Congress repassed it without record vote in the

United States of America. In that year, however, Con-

House and 78-1 in the Senate. Wilson’s successor, Presi-

gress passed the somewhat misnamed Chinese Exclusion

dent Warren G. Harding, signed it in May 1921.

Act (it barred only Chinese laborers) and began a 61-year

period of ever more restrictive immigration policies. By

1917, immigration had been limited in seven major ways.

First, most Asians were barred as a group. Among immi-

grants as a whole, certain criminals, people who failed to

meet certain moral standards, those with various diseases

and disabilities, paupers or “persons likely to become a

public charge,” some radicals, and illiterates were specifi-

cally barred. Yet, in spite of such restrictions, total immi-

gration – except during the difficult years of World War I

78

Immigration Quotas of the 1920s

If the consular officer believes that the applicant may

probably be a public charge at any time, even during a

considerable period subsequent to his arrival, he must

The 1921 act was a benchmark law placing the first

refuse the visa.

numerical limits, called quotas, on most immigra-

tion. A similar but more drastic version – the version

But even with the new restrictions, significant numbers

that Lyndon Johnson complained about – was enacted in

of immigrants continued to be admitted throughout the

1924. Then and later attention focused on the quotas,

1920s. In fact, the 1929 figure – almost 280,000 new im-

but they did not apply to all immigrants. Two kinds

migrants – would not be reached again until 1956. The

of immigrants could be admitted “without numerical

Great Depression and World War II reduced immigra-

limitation”: wives – but not husbands – and unmarried

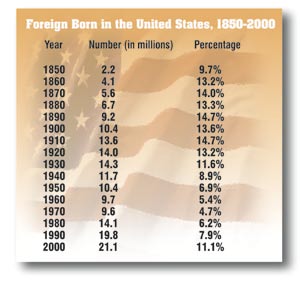

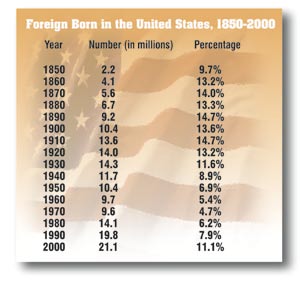

tion drastically. As Table 2 on page 81 shows, both the

children under 18 of U.S. citizens, and immigrants from

number and incidence of foreign-born in the nation fell.

Western Hemisphere nations.

In each census from 1860 to 1920 the census recorded

Nations outside the Western Hemisphere were as-

that about one American in seven was foreign-born; by

signed quotas based origi-

1970 that figure had dropped

nally on the percentage of the

to fewer than one in 20.

population from that nation

Americans came to believe

among the foreign-born as

that the era of immigration was

recorded in the census of 1890,

over. The leading historian

which restrictionists called the

of American nativism, John

Anglo-Saxon census because

Higham, would write in his

it preceded the large influx of

1955 classic, Strangers in the

Southern and Eastern Europe-

Land, that:

ans. (After 1929 an allegedly

scientific method was used to

Although immigration of

reduce immigration even fur-

some sort would continue, the

ther.) Under both regimens,

vast folk movements that had

nations of Northwest Europe

formed one of the most funda-

got the lion’s share of new slots

Many poor immigrants, often from Eastern Europe,

mental social forces in Ameri-

entered the United States in the early 20th century through the ship terminal for immigrants, even though

can history had been brought

on Ellis Island, offshore New York City. Once a quarantine station,

already for decades most immi-

Ellis Island is now a museum.

to an end. The old belief in

grants had come from Eastern and Southern Europe.

America as a promised land for all who yearn for free-

The 1924 law also barred “aliens ineligible to citizen-

dom had lost its operative significance.

ship” – reflecting the fact that American law had, since

1870, permitted only “white persons” and those “of

Although no one seems to have perceived it, the era of

African descent” to become naturalized citizens. The

ever increasing immigration restriction had come to an

purpose of this specific clause was to keep out Japanese,

end a dozen years before.

as other Asians had been barred already. (American law

at the time defined Asians in terms of degrees of latitude

and longitude, a provision that left only those living west

Refugees and Other Wartime

of Afghanistan eligible for immigration to the United

States.) And, as a further control, all immigrants, quota

Changes

and non-quota, were required to obtain entry visas into

the United States from U.S. consuls in their country of

In December 1943, at the urging of President Franklin

origin before leaving. While some American foreign ser-

D. Roosevelt, who wished to make a gesture of sup-

vice officers were “immigrant friendly,” many, perhaps

port to a wartime ally, Congress repealed the 15 statutes

most, refused visas to persons who were legally eligible

excluding immigrants from China, gave a minimal im-

for admission. The State Department’s instructions to its

migration quota to Chinese, and, most important of all,

consular officials emphasized rejection rather than admis-

made Chinese aliens eligible for naturalization. Three

sion. A 1930 directive, for example, provided that:

years later Congress passed similar laws giving the same

rights to Filipinos and “natives of India,” and in 1952

79

it erased all racial or ethnic bars to the acquisition of

find ways in which the United States could fulfill its “re-

American citizenship. Unlike immigration legislation of

sponsibilities to these homeless and suffering refugees of

the pre-World War II era, these and many subsequent

all faiths.” This is the first presidential suggestion that

changes in laws were motivated by foreign policy con-

the nation had a “responsibility” to accept refugees. It

cerns rather than concern about an anti-immigrant back-

has been echoed by each president since then.

lash among domestic constituents.

Truman himself sent no program to Congress. We

In addition, before 1952 other changes had taken place

now know, as many suspected then, that the White

as well in American policy. It had begun to make special

House worked closely with a citizens committee which

provision for refugees. In the run-up to World War II,

soon announced a goal of 400,000 refugee admissions.

Congress had refused to make such provision, most nota-

Success came in two increments. In June 1948, Congress

bly by blocking a vote on a bill admitting 20,000 German

passed a bill admitting 202,000 DPs, but with restrictions

children, almost all of whom would have been Jewish.

that many refugee advocates felt discriminated against

Former President Herbert Hoover backed it; President

Jews and Catholics. Truman signed it reluctantly, know-

Roosevelt privately indicated that he favored it but in the

ing that was the best he was going to get from Congress

end refused to risk his prestige by supporting it. Histori-

at that point. Two years later he signed a second bill

ans and policy makers would come,

which increased the total to 415,000

in the wake of the Holocaust, to

and dropped the provisions that he

condemn American failure to pro-

had complained about.

vide a significant haven for refugees

To create the illusion for their

from Hitler, though in point of fact

edgy constituents that the tra-

many Jewish refugees did make it

ditional quota system was still

on their own to American shores.

intact, Congress pretended that

Vice President Walter Mondale

the immigrants admitted by these

spoke for a consensus in 1979 when

bills above their national quotas

he judged that the United States

represented, in essence, “mort-

and other nations of asylum had at

gages” that would be “paid off” by

least in this sense “failed the test

reducing quotas for those nations in

of civilization” before and during

future years. This manifestly could

World War II by not being more

not be done. To cite an extreme

unreservedly generous to Hitler’s

example, the annual Latvian quota

potential victims.

of 286 was soon “mortgaged” until

Thus, the first of three bit-

the year 2274! Congress quietly

ter post-World War II legislative

cancelled all such “mortgages” in

battles over immigration policy

1957.

was fought between 1946 and 1950

In the event some 410,000 DPs

and focused on refugees. By the

were actually admitted. Only

end of 1946, some 90 percent of

about one in six were Jews; almost

the perhaps 10 million refugees in

as many, about one in seven, were

Europe had been resettled largely

Christian Germans expelled from

in their former homelands. The remainder, referred to as

Czechoslovakia and other Eastern European nations.

displaced persons, or DPs, were people who literally had

Most of the rest were Stalin’s victims, persons who

no place to go. Although DPs were often perceived as

had been displaced by the Soviet takeover of Eastern

a “Jewish problem,” only about a fifth of the 1.1 million

Europe, mainly Poles and persons from the Baltic

remaining DPs were Jews. Many of these wished to go

Republics.

to Palestine, then mandated to Britain, which refused to

allow them to enter.

President Harry S Truman tried for nearly two years

to solve the problem by executive action because Con-

gress and most Americans were opposed to any increase

in immigration in general, and to Jewish immigration in

particular. At the beginning of 1947 he asked Congress to

80

Continuing Controversy Over the numbers of Hungarian, Cuban, Tibetan, or Southeast Asian refugees and Congress would later regularize that

Quota System

action.

Analysis of all admissions during the 13 years that the

INA was in effect (1953-65) shows that some 3.5 million

While the immediate postwar refugee battle ended immigrants legally entered the U.S. Just over a third in favor of admitting at least some refugees, the

were quota immigrants. Non-quota immigrants were an

bitterness about immigration continued in an ongo-

absolute majority in every single year. Asian immigrants,

ing debate about revising the basic statutes largely

supposedly limited under an “Asia-Pacific triangle”

unchanged since 1924. The resulting statute, the 1952

clause to 2,000 per annum, actually numbered 236,000,

Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), also known as

almost 10 times the prescribed amount. Family mem-

the McCarran-Walter Act, was passed over Truman’s

bers of native-born or newly naturalized Asian Americans

veto while the Korean War raged. President Truman and

accounted for most of these. In addition, the INA years

most other liberals (but, interestingly, not Senator – later

mark the first period in American history in which Euro-

President – Lyndon

pean immigrants did

Johnson) were repelled

not dominate free im-

by a kind of side issue:

migration: 48 percent

the act’s Cold War

were from Canada, the

aspects which applied

Caribbean, and Latin

a strict ideological

America, with the

litmus test not only to

largest number from

immigrants but also

Mexico. Seven per-

to visitors. Under the

cent were from Asia,

provisions of the act,

and only 43 percent

many European intel-

from Europe.

lectuals, such as Jean

Paul Sartre, could not

The 1965

lecture at American

universities.

Immigration

Truman’s veto mes-

sage (overridden in

Act

the end by Congress),

praised the act’s aboli-

Although the

tion of all purely racial

national origins

and ethnic bars to

system was no longer

naturalization per se,

dominant, in the 1960s

its expansion of fam-

its last-ditch defense

ily reunification, and

was led in the Sen-

elimination of gender

ate by Sam J. Ervin,

discrimination. But the president said the INA “would

a North Carolina Democrat, who later, in the 1970s, was

continue, practically without change, the national origins

to become a hero to liberals for his role in the Watergate

quota system.” President Truman and most subsequent

hearings. But, in 1965, Ervin took a conservative stance,

commentators really failed to understand the full poten-

arguing that the existing quota system, as modified, was

tial impact of the limited changes wrought by the

not discriminatory but was rather “like a mirror reflecti