parks and beaches, swimming pools, libraries, concert

Desegregation of public schools, enthusiasts like Mar-

halls, and movie theaters – further separated the races.

shall believed, would not only promote equality of op-

Negro travelers on southern highways never knew where

portunity in education; it would also advance interracial

they might find a bed for the night – or even a bathroom.

toleration. In time, the races might become integrated in

Some recreational areas posted signs, “Negroes [the word

a world wherein skin color would no longer cripple one’s

then used to identify African Americans] and Dogs Not

chances in life.

Allowed.”

This rigidly enforced system afflicted public education

at every level. All white state universities in the South

64

What Led to the Brown Decision segregation in the schools.

In retrospect, the decision to fight school segrega-

tion seems to have been obvious and necessary. At the

The Brown decision arose from the efforts of two

time, however, it was a highly controversial move. Many

groups of activists. The first were black parents

Negroes had no particular wish to send their children to

and liberal white allies who resolved to fight discrimina-

schools with whites. Other Negroes feared that deseg-

tion. Among the earliest of these activists were parents

regation – if it ever could be achieved – would lead to

in Clarendon County, South Carolina, who in 1947

the closing down of their schools, which, though starved

demanded provision of school buses for their children.

for resources, were nonetheless important institutions of

Parents in four other segregated districts – in the states

employment and of solidarity in the South. The decision

of Virginia, Delaware, and Kansas, and in the District

to challenge segregation head-on, moreover, provoked

of Columbia – also sought legal assistance. The Brown

even greater anger among southern whites. Governor

case, combining these five protests into one, took its

Herman Talmadge of Georgia declared that he would

name from Oliver Brown, a welder and World War II

never accept integrated schools. He later exclaimed that

veteran whose daughter, Linda, was barred from attend-

desegregation would lead to racial intermarriage and to

ing a white elementary school close to her

“mongrelization of the races.”

home in Topeka, Kansas. Instead, she had

But Marshall and his allies pressed

to arise early, walk across dangerous railroad

ahead, shepherding all five cases through

World War II,

switching yards, and cross Topeka’s busiest

the lower federal courts between 1950 and

commercial street in order to board a bus to

1952. Though they lost most of these cases

having been waged

take her to an all-Negro school.

– judges refused to overrule Plessy – they

At first, Negro parents did not dare to chal-

as a fight

took heart from wider developments at the

lenge segregation. Instead, they demanded

time that promised to advance better race

for democracy,

real equality within the “separate but equal”

relations. World War II having been waged

system. In doing so, they aroused fierce local

as a fight for democracy exposed the evils of

had dramatically

resistance. Whites fired black plaintiffs from

racism. American statesmen such as

their jobs and cut off their credit at local

exposed the

President Harry Truman, leading the West

banks. In Clarendon County, hostile whites

in the Cold War, were acutely aware that

evils of

later burned one of the churches of the Rev.

racial segregation in the United States,

Joseph DeLaine, a Negro protest leader.

mocking American claims to lead the “Free

racism.

When white opponents fired at his home in

World,” had to be challenged. Moreover,

the night, he shot back, jumped into a car,

millions of southern Negroes were then

and fled. South Carolina authorities branded

moving to the North, where they were a

him as a fugitive from justice, and he dared

great deal freer to organize and where their

not return to his home state.

votes could affect the outcome of local

The second group of activists consisted of lawyers

and national elections.

– most of them Negroes – who worked for the

For these and other reasons, many white Americans

Legal Defense Fund (LDF), an autonomous arm of the

in the North in the early 1950s were developing doubts

National Association for the Advancement of Colored

about segregation. As one writer later put it, “There was

People (NAACP). Chief among them was Marshall, a star

a current of history, and the Court became part of it.”

graduate of Howard University Law School, a predomi-

Truman, sensitive to the power of this current, had

nantly black school in Washington, D.C., that trained

ordered desegregation of America’s armed forces in 1948.

many bright attorneys in the 1930s and 1940s. Marshall,

His Justice Department supported Marshall’s legal briefs

a folksy and courageous advocate, had long been manag-

when the Brown cases first reached the Supreme Court

ing cases on behalf of Negro causes, notably the deseg-

for hearing in December 1952.

regation of law schools. Responding to pleas from black

The Court, however, was an uncertain quantity. Chief

parents in Clarendon County, he engaged the LDF in

Justice Fred Vinson, who hailed from the border state of

the struggle to promote racial equality in public school

Kentucky, was one of at least three of the nine justices

systems. In 1950, deciding that true equality could never

on the Court who were believed to oppose desegregation

exist within a separate but equal system, he and other

of the schools at the time. Two other justices were appar-

NAACP leaders decided to call for the abolition of racial

ently undecided. It was clear that the Court was deeply

65

divided on the issue – so much so that advocates of racial

Putting the Court’s Ruling Into

justice dared not predict victory.

At this point, luck intervened to help the Legal De-

Practice

fense Fund and its plaintiffs. In September 1953, Vinson

died suddenly of a heart attack. Hearing of Vinson’s

death, Justice Felix Frankfurter, a foe of the chief, reput-

This was an historic decision. More than 50 years

edly commented to an aide, “This is the first indication

later, it remains one of the most significant Su-

I have ever had that there is a God.” To replace Vinson,

preme Court rulings in U.S. history. In focusing on public

President Dwight Eisenhower appointed California Gov-

schools, Brown aimed at the core of segregation. It subse-

ernor Earl Warren as chief. In doing so, the president, a

quently served as a precedent for Court decisions in the

conservative on racial issues, did not anticipate that War-

late 1950s that ordered the desegregation of other public

ren would advocate the desegregation of schools. But the

facilities – beaches, municipal golf courses, and (follow-

new chief justice soon surprised him. A liberal at heart,

ing a year-long black boycott in 1955-56) buses in Mont-

Warren moved quickly to persuade his colleagues to over-

gomery, Alabama. It was obvious, moreover, that no other

turn school segregation.

governmental institution

In part because of War-

in the early 1950s – not the

ren’s efforts, the doubters

presidency under Eisen-

on the Court swung behind

hower, not the Congress

him. Announcing the Brown

(which was dominated by

decision in May 1954,

southerners) – was prepared

Warren stated that racial

to attack racial segregation.

segregation led to feelings

It was no wonder that El-

of inferiority among Negro

lison, Marshall, and many

children and damaged their

others hailed the ruling as a

motivation to learn. His

pivotal moment in Ameri-

opinion concluded, “In the

can race relations.

field of public education

It soon became obvi-

the doctrine of ‘separate but

ous, however, that Brown

equal’ has no place. Sepa-

would not work wonders.

rate educational facilities

Like many Supreme Court

are inherently unequal.”

decisions in American his-

Negro children, he argued,

tory, the ruling was limited

had been deprived of the

to specific issues raised by

“equal protection” of the

the cases. Thus, it did not

laws guaranteed by the 14th

explicitly concern itself

Amendment to the United

with many other forms of

States Constitution.

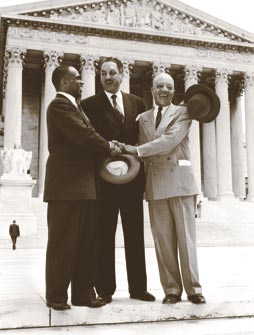

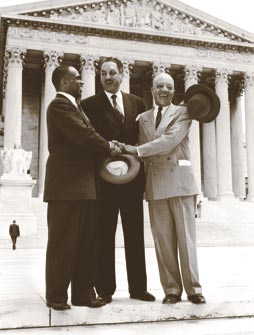

This group of lawyers (left to right, George E.C. Hayes, Thurgood Marshall, and James M. Nabrit) surmised that appealing to the courts was the most likely way to achieve the political goal of abolishing segregation. Marshall later became a Supreme Court justice.

66

racial segregation – as in public accommodations – or

with more informal but pervasive forms of racial dis-

Impetus for the Civil Rights

crimination, as in voting and employment. It deliberately

avoided challenging a host of state laws that outlawed

Movement

racial intermarriage. Targeting only publicly sponsored

school segregation, Brown had no direct legal impact on

Thereafter, liberals finally made progress in their

schools in other parts of the nation. There, racially imbal-

fight for the desegregation of schools. The driving

anced schools were less the result of state or local laws

force behind their gains was the civil rights movement,

(of de jure discrimination) than of informal actions ( de

which swelled with enormous speed and power between

facto discrimination) based on the reality of races inhabit-

1960 and 1965. In 1964-65, pressure from the movement

ing different neighborhoods. In the 1950s, as later, de

compelled Congress to approve two historic laws, the

facto segregated neighborhoods – and schools – flour-

Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of

ished in the American North.

1965. Vigorously enforced by federal officials within the

The Brown decision was cautious in another way:

administration of President Lyndon Johnson (1963-69),

because Warren and his fellow justices feared to push

these measures succeeded in virtually demolishing a

segregating districts too hard, they did not order the im-

host of discriminatory racial practices, including segrega-

mediate dismantling of school segregation. Instead, they

tion in public accommodations. In particular, the Civil

deliberated for a year, at which point they issued a sec-

Rights Act authorized cutting off federal financial aid to

ond ruling, Brown II, which avoided specifying what sort

local school districts that continued to evade the mes-

of racial balance might constitute compliance. Refusing

sage of Brown. Responding to the more militantly liberal

to set a specific deadline for action, Brown II stated that

temper of the times, the federal courts, including the

desegregation should be carried out with “all deliberate

Supreme Court, began ordering school officials not only

speed.” This fuzzy phrase encouraged southern white

to desegregate without delay but also to establish “racial

authorities to procrastinate and gave federal courts in

balance.” By the late 1970s, roughly 40 percent of black

the South little guidance in resolving disputes that were

public school pupils in the South were attending schools

already arising.

in which the student population was at least 50 percent

It is virtually certain, however, that whatever the

white.

Court might have said in 1954-55, and no matter how

What did the Brown decision have to do with the rise

slowly it was willing to go, southern whites would have

of the civil rights movement – and therefore with these

fought fiercely against enforcement of Brown. Indeed,

dramatic changes? In considering this question, schol-

and most ironically, schools then and later proved the

ars and others have offered varied answers. When the

most sensitive and resistant of America’s public insti-

movement shot forward in the early 1960s, many people

tutions to changes in racial relations. Though many

believed that Brown was a crucial catalyst of it. Then and

districts in the border states slowly desegregated, whites

later they have also argued that this first major decision

in the Deep South (often aided by the Ku Klux Klan

energized and emboldened what became known as the

and other extremist groups) bitterly opposed change.

liberal “Warren Court,” which zealously advanced the

In 1956, virtually all southerners in Congress issued the

rights of minorities, criminal defendants, poor people,

so-called Southern Manifesto pledging to oppose school

and others in need of legal protection. Among the men

desegregation by “all lawful means.” In 1957, Arkansas

who helped to propel this liberal judicial surge was Thur-

Governor Orval Faubus openly defied the Court, forcing

good Marshall, whom Johnson named as America’s first

a reluctant President Eisenhower – who never endorsed

black Supreme Court justice in 1967.

the Brown decision – to send in federal troops to enforce

Today, most scholars agree that Brown was symboli-

token desegregation of Central High School in Little

cally useful to leaders of the civil rights movement.

Rock. There – as in New Orleans, Nashville, Charlotte,

After all, the law, at last, was on their side. “Separate

and many other places – angry whites took to the streets

but equal” no longer enjoyed constitutional sanction.

in order to harass and intimidate black pupils on their

They also agree that Brown, the first key decision of the

way to school. In 1964, 10 years after Brown, fewer than

Warren Court, stimulated a broader rights consciousness

2 percent of black students in the South attended public

that excited and in many ways empowered other groups

schools with whites.

– women, the elderly, the disabled, gay people, and other

minorities – after 1960. These are the most important

long-range legacies of the decision.

67

It is not so clear, however, that Brown was uniformly

are gone forever.

effective in the task it was supposed to accomplish, which

But it is also obvious that Brown has not changed ev-

was to promote complete desegregation of public school

erything. In the 2000s, considerable racial inequality per-

systems. On the contrary, by 1960 it was apparent that

sists in the United States. The median income of blacks,

the legal strategies employed by men such as Marshall

though far better in real terms than earlier, remains at

had failed to achieve desegregation of the schools. Real-

around 70 percent of median white income. Millions of

izing the limitations of litigation, which moved slowly,

African Americans continue to reside in central city areas

civil rights leaders like the Reverend Martin Luther King

where poverty, crime, and drug addiction remain serious.

Jr., as well as militant activists in organizations like the

Though de jure segregation is, of course, now banned,

Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Student

barriers of income, culture, and mutual distrust still often

Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), seized on

separate the races. Especially in urban areas, public

strategies of direct action. One strategy was “sit-ins,”

schools have re-segregated since the mid-1980s. In the

where crowds of blacks sat down in places they weren’t

‘70s and ‘80s, courts, seeking to create racially balanced

supposed to go in the segregated South. Another was

schools, mandated a certain amount of complex busing

“freedom rides,” where activ-

of pupils from one school district

ists boarded buses headed South

to another, at the local level.

to force desegregation of na-

Labeled “forced busing” by its

tional bus lines and bus terminals

opponents, this action proved

– actions that provoked violent

wildly unpopular among many

responses by mobs of local whites.

whites. Thus, while many

There were also mass demon-

liberals have opposed re-segrega-

strations. These confrontations,

tion in recent years, they have

unleashing violence that flashed

received relatively little support

across millions of TV screens,

from the courts, which since the

shocked Americans into demand-

1990s have generally ruled that

ing that the government take

de facto residential segregation,

action to protect the ideals and

not intentionally racist public

values of the nation.

policies, have promoted this

re-segregating process, and that

The Brown

such segregation is not subject

to further attempts at judicial

Decision Today

reversal. Many black people,

concerned, like whites, above

all with sending their children

to good schools, have concluded

Since the 1950s, America’s

that engaging in protracted legal

race relations have greatly

battles for educational desegre-

improved. White attitudes are

gation plans involving busing or

more liberal. A considerable black

other complicated methods is

middle class has arisen. Some

no longer worth the effort or the

“affirmative action” policies aimed Civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., leading black children expense.

at preventing discrimination,

to all-white schools in Mississippi in 1966. Dr. King became the

Today, the percentage of black

public face of the ‘60s civil rights movement;

scarcely imagined in the 1950s

he was later assassinated.

students in the South that attend

and 1960s, have secured Supreme

white majority public schools has

Court approval. The historic civil rights laws of the 1960s

declined to around 30. Because many northern industrial

continue to enjoy solid political support. Talented African

cities by now have overwhelmingly black populations

Americans have risen to a range of leadership positions,

in parts of their central cores, the percentages of black

including secretary of state of the United States. Thanks

students attending such schools outside the South are

in part to the change in society and culture signaled and

even lower. Hispanic Americans also often attend racially

indeed initiated by Brown, the Bad Old Days of

imbalanced schools. Many schools mainly attended by

constitutionally sanctioned, state-sponsored segregation

minority students are inferior – in per pupil spending

68

and the training of teachers, certainly in levels of student

in the workplace. But in the United States, as else-

achievement – to predominantly white schools in nearby

where in the world, the struggle to create societies where

affluent suburban districts.

all are truly equal has yet to achieve its goal.

If Ralph Ellison or Thurgood Marshall were alive to-

day, each would undoubtedly be pleased that Brown ulti-

James T. Patterson, an historian of modern America, retired from teaching at mately helped to kill de jure school segregation. But they

Brown University in 2002. His recent books include Grand Expectations: would also recognize that the dramatic decision, while a

The United States, 1945-1974 (winner of the Bancroft Prize in history); necessary step toward the promotion of racial justice, did

Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and

not lead to the establishment of a uniformly integrated

Its Troubled Legacy; and Restless Giant: The United States from

society. Whites and blacks in the United States are far

Watergate to Bush v. Gore.

more integrated than they were 50 years ago, especially

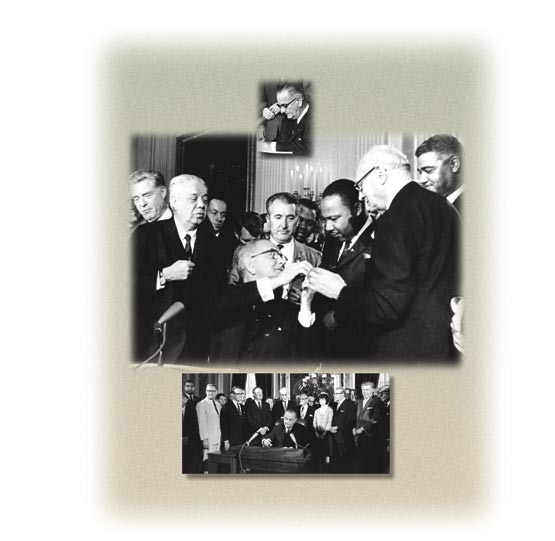

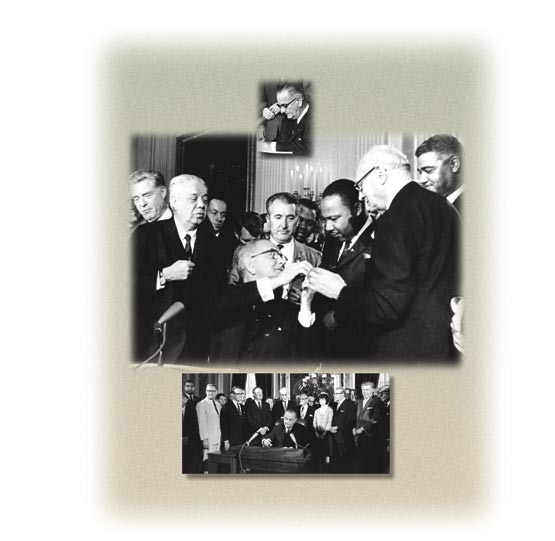

Brown changed the temper of the times, and led to national civil rights legislation, especially during the presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson (inset top).

Center: Johnson hands Dr. King a pen used to sign the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Below: Johnson signs the Voting Rights Act of 1965, a law that made

it easier for black Americans to vote.

69

As with the Zenger trial centuries earlier, the fate of one uncelebrated citizen changed American law.

By granting Clarence Earl Gideon the right to a defense attorney at state expense in 1963, the Supreme Court made it easier for the poor to de