CHAPTER II

THE QUEEN AND THE DUCHESS

A YEAR after the accession of William and Mary, and before any of the bitternesses and conflicts above recorded had openly begun, the only child of Anne on whose life any hopes could be built was born. Her many babies had died at birth or immediately after, and their quick and constant succession, as has been said, was the distinguishing feature of her personal life. But after the Revolution, when everything was settling out of the confusion of the crisis, and when as yet no further family troubles had disclosed the family rancors and disagreements, in the country air of Hampton Court, where the new king and queen were living, a little prince was born. Though he was sickly at first, like all the rest, he survived the dangers of infancy, and, called William after the king, and bearing from the first day of his life the title of Duke of Gloucester, was received joyfully by the nation at large and everybody concerned as the authentic heir to the crown. This child kept, it would seem, a little hold on the affections of the childless Mary during the whole course of the quarrel with his mother, bitter as it was, and continued an object of interest and kindness to William as long as he lived. The interposition of the quaint and precocious boy, with his big head, his premature enlightenment as to what it was and was not prudent to say, his sparkle of childish ambition, and all his old-fashioned ways, made a curious and welcome diversion in the troubled scene where nothing was happy, not even the child. He was the chief occupation of Anne’s life when comparative peace followed the warlike interval above related, and a cold and forced civility replaced the active hostilities which for years had been raging between the court and the household of the princess.

THE DUKE OF GLOUCESTER.

ENGRAVED BY R. G. TIETZE, FROM MEZZOTINT BY JOHN SMITH, AFTER THE

PAINTING BY SIR GODFREY KNELLER.

Anne has never got much credit for her forbearance and self-effacement at the critical moments of her career. But it is certain that she might have given William a great deal of trouble had she asserted her rights as Mary’s successor, as she might also have done at the time of the first settlement. No doubt he would on both occasions have carried the day, and with this certainty the historians have been satisfied, without considering that a woman who was not of a lofty character, and who was a Stuart, must have felt it doubly bitter to find herself the subject of a gloomy brother-in-law who slighted her, and who, her rasher partizans did not hesitate to say, ought to have been her subject so long as he remained in England after her sister’s death, and not she his. The absence of any attempt on her part to disturb or molest, nay, her little advances, her letters of condolence, and of congratulation the first time that a victory gave occasion for it, showed no inconsiderable magnanimity on the part of the prosaic princess—all the more that she had not been in the habit, as is usual among women, of putting the scorns she had suffered to another woman’s account, and holding Mary responsible, but had uniformly attributed to the “Dutch monster,” the Caliban of her correspondence, all the slights that were put on her—all the more that William did very little to encourage any overtures of friendship. He received her after his wife’s death, and they are said by one of her attendants to have wept together when the unwieldy princess, then unable to walk, was carried in her chair into the very presence-chamber. But if a common emotion drew them together at this moment, it did not last; and in the diminished ceremonial of the bereaved court, Anne had but scant respect and no welcome. But she made no further complaint, and did what she could to keep on terms of civility at least with her brother-in-law, writing to him little letters of politeness, notwithstanding the disapproval of Lady Marlborough, who was of no such gentle temper, and the absence of all response from William. He, with all his foreign wars and home troubles, solitary, sad, broken in health and in life, had little heart, we may suppose, for those commonplace advances from a woman he had never been able to tolerate. But though Anne’s relations with the king were scarcely improved, her position in respect to the courtiers who had abandoned her in her sister’s lifetime was different indeed. Lady Marlborough describes this with her usual force.

And now it being quickly known that the quarrel was made up, nothing was to be seen but crowds of people of all sorts flocking to Berkeley House to pay their respects to the prince and princess; a sudden alteration which I remember occasioned the half-witted Lord Carnarvon to say one night to the princess as he stood close by her in the circle, “I hope your highness will remember that I came to wait upon you when none of this company did,” which caused a great deal of mirth.

Meanwhile, the little boy, the heir of England, interposes his quaint little figure with that touch of nature which always belongs to a child, in the midst of all the excitement and dullness, awakening a certain interest even in the solitary and bereaved life of William, and filling his mother’s house with tender anxieties and pleasures. He was sickly and feeble from his childhood, but early learned the royal lesson of self-concealment, and was cuffed and hustled by the anxious cruelty of love into the use of his poor little legs years after his contemporaries had been in full enjoyment of their liberty. It is characteristic of the self-absorbed and belligerent chronicler of the princess’s household, whose narrative of all the quarrels and struggles of royal personages is so vivid, that she has very little to say about either the living or dying of the only child who was of such importance both to her mistress and to the country. His little existence is pushed aside in Lady Marlborough’s record, and but for a little squabble over the appointment of the duke’s “family,” which she gives with great detail, we should scarcely have known from her that Anne had tasted that happiness of maternity which is so largely weighted with pains and cares. But the story of little Gloucester’s life, as found in the more familiar record of his waiting-gentleman, Lewis Jenkins, is both attractive and entertaining. The little fellow seems to have been full of lively spirit and observation, active and restless in spite of his feebleness, full of a child’s interest in everything about him, and of precocious judgment and criticism. Some of the stories that are told of him put these gifts in a startling light. “Who has taught you to say such words?” his mother asks him when the child has been betrayed into innocent repetition of the oaths he had heard from his attendants. The boy pauses before he replies. “If I say Dick Dewey,” he whispers to a favorite lady, “he will be sent down-stairs. Mama, I invented them myself,” he adds aloud. The little being moving among worlds not realized, learning to play his little part, taking his cue from the countenances round him, forming his little policy in the twinkling of an eye, could not have had a better representative. His careless indifference to his chaplain’s religious services, but happy learning of little prayers and verses with the old lady to whom he takes a fancy, his weariness of lessons, yet eager interest in the diagrams that drop from Lewis Jenkins’s pocket-book, and in all the bits of history he can induce his Welsh usher to tell him, and all the rest of his innocent childlike perversities, awaken in us an amused yet pathetic interest. A troublesome, lovable, perverse, delightful child, not always easy to manage, constantly asking the most awkward questions, full of ambition and energy and spirit and foolishness, the dull prince’s somewhat tedious house brightens into hope and sweetness so long as he is there.

In every respect this was the brightest moment of Anne’s life. There was no longer any possibility of treating the next heir to the crown, the mother of the only prince in whom the imagination of England could take pleasure, with slighting or contumely. She was permitted to have her share of the honors and comforts of English royalty. St. James’s old red-brick palace was given over to her as became her position; and, what was more wonderful, Windsor Castle, one of the noblest of royal dwellings, became the country-house of Anne and her boy. King William preferred Hampton Court, with its Dutch gardens, in which he could imagine himself at home: the great feudal castle, erecting its massive towers from the crest of the gentle hill which has the value of a much greater eminence in the midst of the broad plain that sweeps forth in every direction round, was not, apparently, to his taste. And few prettier or more innocent scenes have been associated with its long history than those in which little Gloucester was the chief actor. He had a little regiment of boys of his own age whom it was his delight to drill and lead through a hundred mock battles and rapid skirmishings, mischievous little urchins who called themselves the Duke of Gloucester’s men, and played their little pranks like their elders, as favorites will. When he went to Windsor, four Eton boys were sent for to be his playmates, one of them being young Churchill, the son of Lady Marlborough. The little prince chose St. George’s Hall for the scene of his mimic battles, and there the little army stormed and besieged one another to their hearts’ content. When his mother’s marriage-day was celebrated, he received his parents with salvos of his small artillery, and, stepping forth in his little birthday-suit, paid them his compliment: “Papa, I wish you and Mama unity, peace, and concord, not for a time, but forever,” said the serious little hero. One can fancy Anne, smiling and triumphant in her joy of motherhood, with her beautiful chestnut curls and sweet complexion and placid roundness, leaning on good George’s arm,—her peaceful companion, with whom she had never a quarrel,—and admiring her son’s infant wisdom. It was their happy time: no cares of state upon their heads, no quarrels on hand, Sarah of Marlborough, let us hope, smiling too, and at peace with everybody, her own boy taking part in the ceremonial.

The little smoke and whiff of gunpowder, the little gunners at their toy artillery, the great hall still slightly athrill with the mimic salute, add something still to the boundless hopefulness of the scene; for why should not this little English William grow up as great a soldier and more fortunate than his grim godfather, and subdue France under the feet of England, and be the conqueror of the world? All this was possible in those pleasant days.

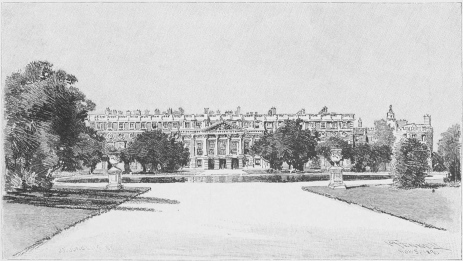

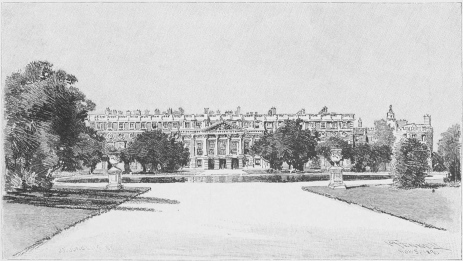

GARDEN FRONT, HAMPTON COURT.

DRAWN BY JOSEPH PENNELL, ENGRAVED BY J. F. JUNGLING.

On another occasion there was a great chapter of Knights of the Garter to witness the installation of little Gloucester in knightly state as one of the order. The little figure, seven years old, seated under the noble canopywork in St. George’s beautiful chapel, scarcely visible over the desk upon which his prayer-book was spread out, gazing with blue eyes intent, in all the gravity of a child, upon the great English nobles in their stalls around him, listening to the voices of the choristers pealing high into space, makes another touching picture. King William himself had buckled the garter round the child’s knee and hung the jewel about his neck,—St. George slaying his dragon, that immemorial emblem of the victory over evil; and no doubt in the vague grandeur of childish anticipation, the boy felt himself ready to emulate the feat of the patron saint. He was a little patriot too, eager to lend the aid of his small squadron to his uncle when William went away to the wars, and bringing a smile even upon that worn and melancholy face as he manœuvered his little company and showed how they would fight in Flanders when the moment came. When William was threatened with assassination and the country woke up to feel that though she did not love him it would be much amiss to lose him, little Gloucester, at eight, was one of the most loyal. Taking counsel with his little regiment, he drew up a memorial, written out, no doubt, by the best master of the pen among them, with much shedding of ink, if not of more precious fluid. “We, your Majesty’s subjects, will stand by you while we have a drop of blood,” was the address to which the Duke of Gloucester’s men set all their tiny fists. The little duke himself, not content with this, added to it another address of his own:

I, your Majesty’s most dutiful subject, had rather lose my life in your Majesty’s cause than in any man’s else; and I hope it will not be long ere you conquer France.

GLOUCESTER.

Heroic little prince!—a Protestant William, yet a gallant and gentle Stuart. With this heart of enthusiasm and generous valor in him, what might he not have done had he ever lived to be king? These marred possibilities, which are so common in life, are almost the saddest things in it, and that must be a heart very strong in faith that is not struck dumb by the withdrawal from earth’s extreme need of so much faculty that seemed created for her help and succor. It certainly awoke a smile, and might have drawn an iron tear down William’s cheek, to see this faithful little warrior ready to “lose his life” in his defense. And the good pair behind, George and Anne, who had evidently suffered no treacherous suggestion to get to the ear of the boy,—no hint that William was a usurper, and little Gloucester had more right than he to be uppermost,—how radiant they stand in the light of their happiness and hope! The spectator is reluctant to turn the page to the coming gloom.

“When the Duke of Gloucester was arrived at an age to be put into men’s hands,” William’s relenting and change of mind was proved by the fact that Marlborough, who had been in disgrace all these years, and whom only the constant favor of Anne had kept out of entire obscurity, was recalled into the front of affairs in order to be made “governor” of the young prince. It is true that this gracious act was partially neutralized by the appointment of Bishop Burnet as little Gloucester’s tutor, a choice which was supposed to be as disagreeable to Anne as the other was happy. No distinct reason appears for this sudden and extraordinary change. Marlborough’s connection with the family of the princess made him indeed peculiarly suitable to have the charge of her son, but William had not hitherto shown any desire to honor her likings; and this was not reason enough for all the other marks of favor bestowed upon him, bringing him back at once from private life and political disgrace to a position as high as any in the kingdom. Burnet himself did by no means relish the honor thus thrust upon him. He was almost disposed, he tells us, “to retire from the court and town,” much as that would have cost him, rather than take upon him such a charge. But the pleasure of believing that “the king would trust that care only to me,” and also an unexpected “encouragement” received from the princess, decided him to make the experiment. The little pupil was about nine when he came into the bishop’s hands, and he gives the following account of his charge:

I had been trusted with his education now for two years, and he had made amazing progress. I had read over the Psalms, Proverbs, and Gospels with him, and had explained things that fell in my way very copiously; and was often surprised with the questions that he put to me, and the reflections that he made. He came to understand things relating to religion beyond imagination. I went through geography so often with him that he knew all the maps very particularly. I explained to him the forms of government in every country, with the interests and trades of that country, and what was both bad and good in it. I acquainted him with all the great revolutions that had been in the world, and gave him a copious account of the Greek and Roman histories of Plutarch’s lives; the last thing I explained to him was the Gothic constitution and the beneficiary and feudal laws: I talked of these things at different times more than three hours a day; this was both easy and delighting to him. The king ordered five of his chief ministers to come once a quarter and examine the progress he made; they seemed amazed both at his knowledge and the good understanding that appeared in him; he had a wonderful memory and a very good judgment.

Poor little Gloucester! The genial bishop breaking down all this knowledge into pleasant talks so that it should be “both easy and delighting,” and his lessons in fortification, which were more delightful still, and his own little private princelike observation of men’s faces and minds, were all to come to naught. On his eleventh birthday, amid the feastings and joy, a sudden illness seized him, and, a few days after, the promising boy had ended his bright little career. As a matter of course, blame was attached to the doctor who attended him, and who had bled him in the beginning of a fever; but this was almost universally the case in the then state of medical science. “He was the only remaining child,” the bishop says, “of seventeen the princess had borne, some to the full time and the rest before it. She attended on him during his sickness with great tenderness, but with a grave composedness that amazed all who saw it. She bore his death with a resignation and piety that were indeed very singular.” It would be small wonder indeed if Anne had been altogether crushed by such a calamity. It is said by some historians of the Jacobite party that her mind was overwhelmed by a sense of her guilt toward her own father, and of just judgment executed upon her in the loss of her child, and that she immediately wrote to James, pouring out her whole heart in penitence, and pledging herself to support the claims of her brother should she ever come to the throne. This letter, however, was never found, and does not seem to be vouched for by witnesses beyond suspicion. But for the fact that Anne was stricken to the dust, no parent will need any further evidence. Her good days and hopes were over; henceforward, when she wrote to her dearest friend in the old confidential strain, it was as “your poor unfortunate Morley” that the bereaved mother signed herself. Nothing altered these sad adjectives. She felt herself as poor and unfortunate in her unutterable loss when she was queen as if she had been the humblest woman that ever lost an only child.

Marlborough was absent when his little pupil fell ill, but hurried back to Windsor in time to see him die. It was etiquette in those days that in case of a death the survivors should instantly leave the place in which it had happened, leaving the dead in possession, to lie in state there and receive the homage of curious or interested spectators. But Anne would not be persuaded to leave the place where her child was, and, four or five days after, the little prince was carried solemnly by torchlight through the summer woods, through Windsor Park, and by the river, and under the trees of Richmond, to Westminster: a silent procession pouring slowly through the odorous August night. His little body lay in state in Westminster Hall—a noble chamber for such a tiny sleeper—for five days more, when it was laid with the kings in the great abbey which holds all the greatest of England. A more heartrending episode is not in history.

William did not take any notice of the announcement of the death for a considerable time, which embarrassed the ambassador at Paris greatly on the subject of mourning, and has given occasion for much denunciation of his hardness and heartlessness. When he answered at last, however—though this was not till more than two months after, in a letter to Marlborough—it was with much subdued feeling. “I do not think it necessary to employ many words,” he writes, “in expressing my surprise and grief at the death of the Duke of Gloucester. It is so great a loss to me as well as to all England, that it pierces my heart with affliction.” It seems impossible that the loss of a child who had shown so touching an allegiance to himself should not have moved him; but perhaps there was in him, too, a touch of satisfaction that the rival pair who had been thorns in his flesh since ever he came to England, were not to have the satisfaction of founding a new line. At St.-Germain the satisfaction was more marked still, and it was supposed that the most dangerous obstacle in the way of the young James Stuart was removed by the death of his sister’s heir. We know now how futile that anticipation was; but at the time this was not so clear, and the anxiety of the English parliament to secure before William’s death a formal abjuration of the so-called Prince of Wales shows that the hope was not without foundation.

THE DUKE OF GLOUCESTER

ENGRAVED BY R. A. MULLER, FROM MINIATURE BY LEWIS CROSSE IN THE COLLECTION AT WINDSOR CASTLE; BY SPECIAL PERMISSION OF QUEEN VICTORIA.

This and the new and exciting combination of European affairs produced by what is called the “Spanish Succession,” occupied all minds during the two years that remained of William’s suffering life. It was a moment of great excitement and uncertainty. Louis XIV., into whose hands, as seemed likely, a sort of universal power must fall if his grandson were permitted to succeed to the throne of Spain, had just vowed at the death-bed of James his determination to support the claims of the exile’s son, and, on James’s death, had proclaimed the boy King of England. Thus England had every reason of personal irritation and even alarm for joining in the alliance against the threatening supremacy of France, whose power—had she been allowed to place one of her princes peaceably on the Spanish throne, to which the rich Netherlands still belonged—would have been paramount in Europe. It was on the eve of the great struggle that William died. With a determination equal to that with which he had made head against failing fortune in many a battle-field, he fought for his life, which, at such a crisis, was doubly important to the countries of his birth and of his crown, and to the cause of the Protestant religion and all that we have been taught to consider as freedom throughout Europe. There is something pathetic in the struggle, in the statement of his case, under one name or another as a private individual, that there might be no doubt as to the frankness of the opinions which he caused to be made among the great physicians of Europe. His life in itself could not have been a very happy or desirable one. He had no longer his popular and beloved Mary to leave behind him in England as his representative when he set out for the wars, and there were few in England whom he trusted fully, or who trusted him. To die at the beginning of a great European struggle, leaving the dull people whom he disliked to take his place in England, and the soldier whom he had crushed and subdued and sternly held in the shade as long as he was able, to assume his baton, and win the victories it had never been William’s fortune to gain, must have been bitter indeed. It would appear even that he had entertained some idea of disturbing the natural order of events to prevent this, and that it had been suggested to the Electress Sophia, after poor little Gloucester’s death, that her family should at once be nominated as his immediate successors, to the exclusion of Anne, a proposal which the prudent electress evaded with great skill and ingenuity by representing that the Prince of Wales—who must surely have learned, he and his counselors, wisdom from the failure of his father—was the natural heir, and would, no doubt, do well enough on a trial. Bishop Burnet denies that such a design was ever entertained, but Lord Dartmouth, in his notes upon Burnet, gives the following very distinct evidence on the subject:

I do not know how far the Whig party would trust a secret of that consequence to such a blab as the bishop was known to be: but the Dukes of Bolton and Newcastle both proposed it to me, and used the strongest arguments to induce me to come into it; which was that it would be making Lord Marlborough King at least for the time if the Princess succeeded; and that I had reason to expect nothing but ill-usage during such a reign. Lord Marlborough asked me afterward in the House of Lords if I had ever heard of such a design. I told him Yes, but did not think it very likely. He said it was very true: but by God if ever they attempted it we would walk over their bellies.

Thus until the last moment Anne’s position would seem to have been menaced; but a more impossible scheme was never suggested, for even the idea of Marlborough’s triumph was unable to raise the smallest party against the princess, and to the country in general she was the object of a kind of enthusiasm. The people loved everything in her, even the fact that she was not clever, which of itself is often highly ingratiating with the masses. William, it is said, with a magnanimity which was infinitely to his credit, named Marlborough as his most fit successor in the command of the allied armies before he died. The formal abjuration of the Prince of Wales was made by Parliament only just in time to have his assent, and then all obstacles were removed out of the princess’s way. It was thought by the populace that everything brightened for the new reign. There had been an unexampled continuance of gloomy weather, bad harvests, and clouds and storms. But to great Queen Anne the sun burst forth, the gloom dispelled, the country broke out into gaiety and rejoicing. A new reign full of new possibilities has always something exhilarating in it. William’s greatness was marred by externals and never heartily acknowledged by the mass of the people, but Anne had many claims upon the popular favor. She was a woman, and a kind and simple one. That desertion of her father which some historical writers have condemned so bitterly, had no great effect upon the contemporary imagination, nor, so far as can be judged, upon her own; and it was the only offense that could be alleged against her. She had been unkindly treated and threatened with wrong, which naturally made the multitude strenuous in her cause; and everything conspired to make her accession happy. She was only thirty-seven, and though somewhat unwieldy in person, still preserved her English comeliness, her abundant, beautiful hair, and, above all, the melodious voice by which even statesmen and politicians were impressed. “She pronounced this,” says Bishop Burnet, describing her address to the Privy Council when they first presented themselves before her, “as she did all her other speeches, with great weight and authority, and with a softness of voice and sweetness in the pronunciation that added much life to all she spoke.” The commentators who criticize so sorely the bishop’s chronicles are in entire agreement with him on this subject. “It was a real pleasure to hear her,” says Lord Dartmouth, “though she had a bashfulness that made it very uneasy to herself to say much in public.” Speaker Onslow unites in the same testimony: “I have heard the queen speak from the throne, and she had all the author says here. I never saw an audience more affected; it was a sort of charm. She received all that came to her in so gracious a manner that they went from her highly satisfied with her goodness and her obliging deportment; for she hearkened with attention to everything that was said to her.” Thus all smiled upon Anne in the morning of her reign. Her coronation was marked with unusual splendor and enthusiasm, and though the queen herself had to be carried in a chair to the Abbey, her state of health being such that she could not walk, this did not affect the splendid ceremonial in which even to the Jacobites themselves there was little to complain of, since their hopes that Anne’s influence might advance her father’s young son to the succession after her were still high, notwithstanding that the settlement of the crown upon Sophia of Brunswick and her heirs had already been made.

QUEEN ANNE.

FROM COPPERPLATE ENGRAVING BY PIETER VAN GUNST, AFTER THE PAINTING BY SIR GODFREY KNELLER.

It is needless for us to attempt a history of the great war which was one of the most important features in Anne’s reign. No student of history can be ignorant of its general course, nor of the completeness with which Marlborough’s victories crushed the exorbitant power of France and raised the prestige of England. There is no lack of histories of the great general and his career of victory: how he out-fought, out-marched, and out-generaled all his rivals, and scarcely in his ten years of active warfare encountered one check; how, though he did not accomplish the direct object for which all the bloodshed and toil were undertaken, he yet secured such respect for the English name and valor as renewed our old reputation and made all interference with our natural settlement or intrusion into our private economy impossible forever. “What good came of it at last?” says the poet. But the inquiry, though so plausible, appealing at once to humanity and common sense, is not perhaps so hard to answer as it seems. Up to this time it has been impossible to procure in the intercourse of nations any other effectual arbiter but the sword: a terrible one, indeed, but apparently as yet the only means of keeping a check upon the rapacity of some, and protecting the weakness of others. At all events, whatever individual opinion may be on the point now, there was a unanimous conviction then, and no one doubted at the opening of the war that it was most necessary and just. And of its conduct there has been but one opinion. Contemporaries accused Marlborough of every conceivable wickedness,—of peculation, treachery, even personal cowardice; but no one ventured to say that he was not a great general. And as we have got further and further from the infuriated politics of his time, his gifts and graces, his wisdom and moderation, as well as his wonderful military genius, have been done more and more justice to. Coxe, his special biographer, may be supposed to look with partiality upon his hero; but this cannot be said of more recent writers,—of Lord Stanhope in his tolerant and sensible history, or of Dr. Hill Burton in his sagacious volumes on the reign of Queen Anne.

It is, however, with Marlborough’s wife and not with himself that we are chiefly concerned, and with the stormy course of Anne’s future intercourse with her friend rather than the battles that were fought in her name. It is said that by the time she came to the throne her faithful affectio