CHAPTER III

THE AUTHOR OF “GULLIVER”

THERE are few figures in history, and still fewer in literature, which have occupied so great a place in the world’s attention, or which retain so strong a hold upon its interest, as that of Jonathan Swift, dean of St. Patrick’s. It is considerably more than a century since he died, old and mad and miserable: a man who had never been satisfied with life, or felt his fate equal to his deserts; who disowned and hated (even when he served it) the country of his birth, and with fierce and bitter passion denounced human nature itself, and left a sting in almost every individual whom he loved; a man whose preferment and home were far from the center of public affairs, and who had no hereditary claim on the attention of England. Yet when the English reader, or he who in the farthest corner of the New World has the same right to English literature as that which the subjects of Queen Victoria hold,—as the American does—from the subjects of Queen Anne,—reads the title at the head of this page, neither the one nor the other will have any difficulty in distinguishing among all the ecclesiastical dignitaries of that age who it is that stands conspicuous as the dean. Not in royal Westminster or Windsor is this man to be found; not the ruler of any great cathedral in the rich English midlands where tradition and wealth and an almost Catholic supremacy united to make the great official of the church as important as any official of the state—but far from those influences, half as far as America is now from the center of English society and the sources of power, one of a nation which the most obstinate conservative of to-day will not hesitate to allow was then deeply wronged and cruelly misgoverned by England, many and anxious as have been her efforts since to make amends. Yet among the many strange examples of that far more than republican power (not always most evident in republics) by which a man of native force and genius, however humble, finds his way to the head of affairs and impresses his individuality upon his age, when thousands born to better fortunes are swept away as nobodies, Swift is one of the most remarkable. His origin, though noted by himself, not without a certain pride, as from a family of gentry not unknown in their district, was in his own person almost as lowly and poor as it was possible to be. The posthumous son of a poor official in the Dublin law-courts, owing his education to the kindness, or perhaps less the kindness than the family pride, of an uncle, Swift entered the world as a hanger-on, waiting what fortune and a patron might do for him, a position scarcely comprehensible to young Englishmen nowadays, though then the natural method of advancement. Such a young man in the present day would betake himself to his books, with the practical aim of an examination before him, and the hope of immediate admission through that gate to the public service and all its chances. It is amusing to speculate what the difference might have been had Jonathan Swift, coming raw with his degree from Trinity College, Dublin, shouldered his robust way to the head of an examination list, and thus making himself at a stroke independent of patronage, gone out to reign and rule and distribute justice in India, or pushed himself upward among the gentlemanly mediocrities of a public office. One asks would he have found that method more successful, and endured the desk and the routine of his office, and “got on” with the head of his department, better than he endured the monotony and subjection, the possible slights and spurns of Sir William Temple’s household, which he entered, half servant, half equal, the poor relation, the secretary and companion of that fastidious philosopher? The question may be cut short by the almost certainty that Swift could not have gained his promotion in any such way; but his age had not learned the habit of utilizing education, and he was one of the idle youths of fame. “He was stopped of his degree,” he himself writes in his autobiographical notes, “for dullness and insufficiency, and at last hardly admitted in a manner little to his credit, which is called in that college speciali gratia.” Recent biographers have striven to prove that this really meant nothing to Swift’s discredit, but it is to be supposed that in such a matter he is himself the best authority.

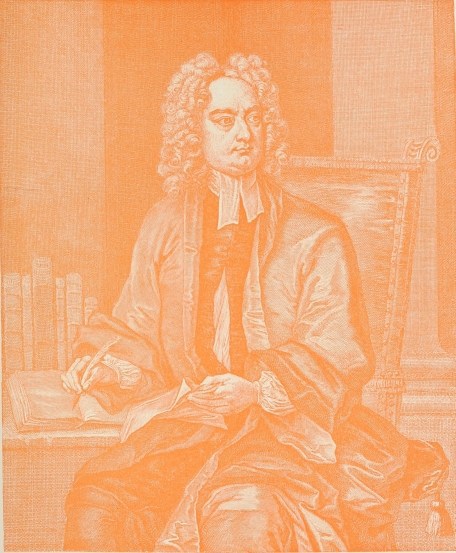

JONATHAN SWIFT.

FROM PHOTOGRAPH OF ORIGINAL MARBLE BUST OF SWIFT BY ROUBILLIAC (1695-1762), NOW IN THE LIBRARY OF TRINITY COLLEGE, DUBLIN.

The life of the household of dependents at Moor Park, where young Swift attended Sir William’s pleasure in the library, while the Johnsons and Dingleys, the waiting-gentlewomen of a system which now lingers only in courts, hung about my lady, her relatives, gossips, servants, is to us extremely difficult to realize, and still more to understand. This little cluster of secondary personages, scarcely at all elevated above the servants, with whom they sometimes sat at table, and whose offices they were always liable to be called on to perform, yet who were all conscious of gentle blood in their veins, and a relationship more or less distinct with the heads of the house, is indeed one of the most curious lingerings of the past in the eighteenth century. When we read in one of Macaulay’s brilliant sketches, or in Swift’s own words, or in the indications given by both history and fiction, that the parson,—perhaps at the great house,—humble priest of the parish, found his natural mate in the waiting-maid, it is generally forgotten that the waiting-maid was then in most cases quite as good as the parson: a gently bred and well-descended woman, like her whom an unkind but not ignoble fate made into the Stella we all know, the mild and modest star of Swift’s existence. It was no doubt a step in the transition from the great medieval household, where the squire waited on the knight with a lowliness justified by his certainty of believing himself knight in his turn, and where my lady’s service was a noble education, the only school accessible to the young gentlewomen of her connection—down to our own less picturesque and more independent days, in which personal service has ceased to be compatible with the pretensions of any who can assume, by the most distant claim, to be “gentle” folk. The institution is very apparent in Shakspere’s day, the waiting-gentlewomen who surround his heroines being of entirely different mettle from the soubrettes of modern comedy. At a later period such a fine gentleman as John Evelyn, in no need of patronage, was content and proud that his daughter should enter a great household to learn how to comport herself in the world. In the end of the seventeenth century the dependents were perhaps more absolutely dependent. But even this, like most things, had its better and worst side.

That a poor widow with her child, like Stella’s mother, should find refuge in the house of her wealthy kinswoman at no heavier cost than that of attending to Lady Temple’s linen and laces, and secure thus such a training for her little girl as might indeed have ended in the rude household of a Parson Trulliber, but at the same time might fit her to take her place in a witty and brilliant society, and enter into all the thoughts of the most brilliant genius of his time, was no ill fate; nor is there anything that is less than noble and befitting (in theory) in the association of that young man of genius, whatsoever exercises of patience he might be put to, with the highly cultured man of the world, the ex-ambassador and councilor of kings, under whose auspices he could learn to understand both books and men, see the best company of his time, and acquire at second hand all the fruits of a ripe experience. So that, perhaps, there is something to be said after all for the curious little community at Moor Park, where Sir William, like a god, made the day good or evil for his people according as he smiled or frowned; where the young Irish secretary, looking but uneasily upon a world in which his future fate was so unassured, had yet the wonderful chance once, if no more, of explaining English institutions to King William, and in his leisure the amusement of teaching little Hester how to write, and learning from her baby prattle—which must have been the delight of the house, kept up and encouraged by her elders—that “little language” which had become a sort of synonym for the most intimate and endearing utterances of tenderness. No doubt Sir William himself (who left her a modest little fortune when he died) must have loved to hear the child talk, and even Lady Giffard and the rest, having no responsibility for her parts of speech, kept her a baby as long as possible, and delighted in the pretty jargon to which foolish child-lovers cling in all ages after the little ones themselves are grown too wise to use it more.

Jonathan Swift left Ireland, along with many more, in the commotion that succeeded the revolution of 1688—a very poor and homely lad, with nothing but the learning, such as it was, picked up in a somewhat disorderly university career. Through his mother, then living at Leicester, and on the score of humble relationship between Mrs. Swift and Lady Temple, of whom the reader may perhaps remember the romance and tender history,—a pleasant association,—he was introduced to Sir William Temple’s household, but scarcely, it would appear, at first to any permanent position there. He was engaged, an unfriendly writer says, “at the rate of £20 a year” as amanuensis and reader, but “Sir William never favoured him with his conversation nor allowed him to sit at table with him.” Temple’s own account of the position, however, contains nothing at all derogatory to the young man, for whom, about a year after, he endeavored, no doubt in accordance with Swift’s own wishes, to find a situation with Sir Robert Southwell, then going to Ireland as secretary of state. Sir William describes Swift as “of good family in Herefordshire.... He has lived in my house, read to me, writ for me, and kept all my accounts as far as my small occasions required. He has Latin and Greek, some French, writes a very good current hand, is very honest and diligent, and has good friends, though they have for the present lost their fortunes,” the great man says; and he recommends the youth “either as a gentleman to wait on you, or a clerk to write under you, or upon any establishment of the College to recommend him to a fellowship there, which he has a just pretence to.” This shows how little there was in the position of “a gentleman to wait on you,” of which the young suitor need have been ashamed. Swift’s own account of this speedy return to Ireland is that it was by advice of the physicians, “who weakly imagined that his native air might be of some use to recover his health,” which he was young enough to have endangered by the temptations of Sir William’s fine gardens; a “surfeit of fruit” being the innocent cause to which he attributes the disease which haunted him for all the rest of his life.

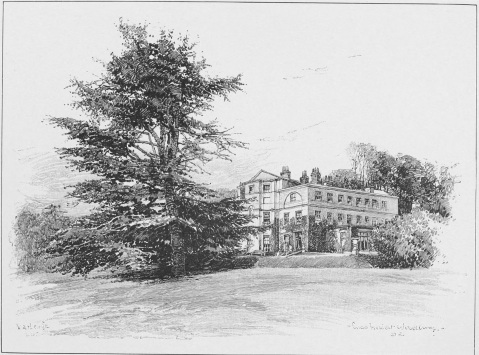

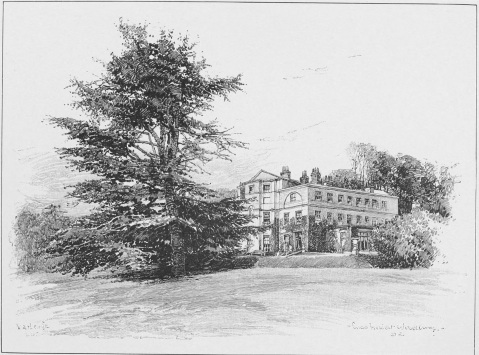

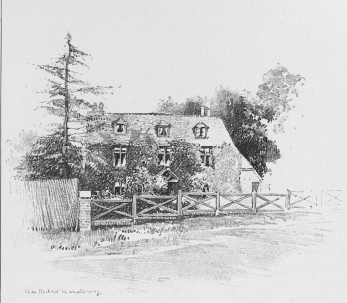

MOOR PARK, RESIDENCE OF SIR WILLIAM TEMPLE, AND OF SWIFT.

DRAWN BY CHARLES HERBERT WOODBURY, ENGRAVED BY R. VARLEY.

His absence, however, from the Temple household was of very short duration, Sir Robert Southwell having apparently had no use for his services, or means of preferring him to a fellowship, and he returned to Moor Park in 1690, where he remained for four years. It was quite clear, whatever his vicissitudes of feeling might have been, that he identified himself entirely with his patron’s opinions and even prejudices, and was a loyal and devoted retainer both now and afterward. When Sir William became involved in a literary quarrel with the great scholar Bentley, young Swift rushed into the field with a jeu d’esprit which has outlived all other records of the controversy. The “Battle of the Books” could hardly have been written in aid of a hard or contemptuous master. Years after, when he had a house of his own and had entered upon his independent career, he turned his little rectory garden into a humble imitation of the Dutch paradise which Temple had made to bloom in the wilds of Surrey, with a canal and a willow walk like those which were so dear to King William and his courtiers. And when Temple died, it was to Swift, and not to any of his nephews, that Sir William committed the charge of his papers and literary remains. This does not look like a hard bondage on one side, or any tyrannical sway on the other, notwithstanding a few often-quoted phrases which are taken as implying complaint. “Don’t you remember,” Swift asks long after, “how I used to be in pain when Sir William Temple would look cold and out of temper for three or four days, and I used to suspect a hundred reasons?” But these words need not represent anything more than that sensitiveness to the aspect of the person on whom his prospects and comfort depend which is inevitable to every individual in a similar position, however considerate and friendly the patron may be. The hard-headed and unbending Scotch philosopher, James Mill, was just as sensitive to the looks of his kind friend and helper in the early struggles of life, Jeremy Bentham, in whose sunny countenance Mill discovered unspoken offense with an ingenuity worthy of a self-tormenting woman. It was natural indeed that Swift, a high-spirited young man, should fret and struggle as the years went on and nothing happened to enlarge his horizon beyond the trees of Moor Park. He was sent to King William, as has been said, when Temple was unable to wait upon his Majesty, to explain to him the expediency of certain parliamentary measures, and this was no doubt intended by his patron as a means of bringing him under the king’s notice. William would seem to have taken a kind of vague interest in the secretary, which he expressed in an odd way by offering him a captain’s commission in a cavalry regiment,—a proposal which did not tempt Swift,—and by teaching him how to cut asparagus “in the Dutch way,” and to eat up all the stalks, as the dean afterward, in humorous revenge, made an unlucky visitor of his own do. But William, notwithstanding these whimsical evidences of favor, neither listened to the young secretary’s argument nor gave him a prebend as had been hoped.

Four years, however, is a long time for an ambitious young man to spend in dependence, watching one hope die out after another; and Swift’s impatience began to be irrestrainable and to trouble the peace of his patron’s learned leisure. Although destined from the first to the church, and for some time waiting in tremulous expectation of ecclesiastical preferment, Swift had not yet taken orders. The explanation he gives of how and why he finally determined on doing so is characteristic. His dissatisfaction and restlessness, probably his complaints, moved Sir William,—though evidently deeply offended that his secretary should wish to leave him,—to offer him an employ of about £120 a year in the Rolls Office in Ireland, of which Temple held the sinecure office of master. “Whereupon [says Swift’s own narrative] Mr. Swift told him that since he had now an opportunity of living without being driven into the Church for a maintenance, he was resolved to go to Ireland and take Holy Orders.” This arbitrary decision to balk his patron’s tardy bounty, and take his own way in spite of him, was probably as much owing to a characteristic blaze of temper as to the somewhat fantastic disinterestedness here put forward, though Swift was never a man greedy of money or disposed to sacrifice his pride to the acquisition of gain, notwithstanding certain habits of miserliness afterward developed in his character. Sir William was “extremely angry”—hurt, no doubt, as many a patron has been, by the ingratitude of the dependent who would not trust everything to him, but claimed some free will in the disposition of his own life. Had they been uncle and nephew, or even father and son, the same thing might easily have happened. Swift set out for Dublin full of indignation and excitement, “everybody judging I did best to leave him,”—but alas! in this, as in so many cases, pride was doomed to speedy downfall.

On reaching Dublin, and taking the necessary steps for his ordination, Swift found that it was needful for him to have a recommendation and certificate from the patron in whose house so many years of his life had been spent. No doubt it must have been a somewhat bitter necessity to bow his head before the protector whom he had left in anger and ask for this. Macaulay describes him as addressing his patron in the language “of a lacquey, or even of a beggar,” but we doubt greatly if apart from prejudice or the tingle of these unforgettable words, any impartial reader would form such an impression. “The particulars expected of me,” Swift writes, “are what relates to morals and learning and the reasons of quitting your honour’s family, that is whether the last was occasioned by any ill action.” “Your honour” has a somewhat servile tone in our days, but in Swift’s the formality was natural. Lady Giffard, Temple’s sister-in-law, in the further quarrels which followed Sir William’s death, spoke of this as a penitential letter, and perhaps it was not wonderful that she should look on the whole matter with an unfavorable eye. No doubt the ladies of the house thought young Swift an unnatural monster for wishing to go away and thinking himself able to set up for himself without their condescending notice and the godlike philosopher’s society and instruction, and were pleased to find his pride so quickly brought down. Sir William, however, it would seem, behaved as a philosopher and a gentleman should, and gave the required recommendation with magnanimity and kindness. Thus the young man had his way.

Swift got a small benefice in the north of Ireland, the little country parish of Kilroot, in which doubtless he expected that the sense of independence would make up to him for other deprivations. It was near Belfast, among those hard-headed Scotch colonists whom he could never endure; and probably this had something to do with the speedy revulsion of his mind. He remained there only a year; and it is perhaps the best proof we could have of his sense of isolation and banishment that this was the only time in his life in which he thought of marriage. There is in existence a fervent and impassioned letter addressed to the object of his affections, a Miss Waring, whom, after the fashion of the time, he called Varina. He does not seem in this case to have had the usual good fortune that attended his relationships with women. Miss Waring did not respond with the same warmth; indeed, she was discouraging and coldly prudent. And he was still pleading for a favorable answer when there arrived a letter from Moor Park inviting his return—Sir William’s pride, too, having apparently broken down under the blank made by Swift’s departure. He made instant use of this invitation—which must have soothed his injured feelings and restored his self-satisfaction—to shake the resolution of the ungrateful Varina. “I am once more offered,” he says, “the advantage to have the same acquaintance with greatness which I formerly enjoyed, and with better prospects of interest”; and though he offers magnanimously “to forego it all for your sake,” yet it is evident that the proposal had set the blood stirring in his veins, and that the dependence from which he had broken loose with a kind of desperation, once more seemed to him, unless Varina had been melted by the sacrifice he would have made for her, to be the most desirable thing in the world.

DEAN SWIFT.

FROM COPPERPLATE ENGRAVING BY PIERRE FOURDRINIER, AFTER A PAINTING BY CHARLES JERVAS.

Macaulay, and after him Thackeray and many less distinguished writers, still persistently represent this part of Swift’s life as one of unmitigated hardship and suffering. The brilliant historian so much scorns the guidance of facts as to say that the humble student “made love to a pretty waiting-maid who was the chief ornament of the servant’s hall,” by way of explaining the strange yet tender story which has been more deeply discussed than any great national event, and which has made the name of Stella known to every reader.

Hester Johnson was a child of seven when young Swift, “the humble student,” went first to Moor Park. She was only fifteen when he returned, no longer as a sort of educated man of all work, but on the entreaty of the patron who had felt the want of his company so much as to forget all grievances. He was not now a humble student, Temple’s satellite and servant, but his friend and coadjutor, fully versed in all his secrets, and most likely already chosen as the guardian of his fame and the executor of his purposes and wishes; therefore it is not possible that Macaulay’s reckless picturesque description could apply to either time. Such an easy picture, however, has more effect upon the general imagination than the outcries of all the biographers, and the many researches made to show that Swift was not a sort of literary lackey, nor Stella an Abigail, but that he had learned to prize the advantages of his home there during his absence from it, and that during the latter part of his life at Moor Park at least his position was as good as that of a dependent can ever be.

Sir William Temple died, as Swift records affectionately, on the morning of January 27, 1699, “and with him all that was good and amiable among men.” He died, however, leaving the young man who had spent so many years of his life under his wing, scarcely better for that long subjection. Swift had a legacy of £100 for his trouble in editing his patron’s memoirs, and he got the profits of those memoirs, amounting, Mr. Forster calculates, to no less than £600—no inconsiderable present; but no one of the many appointments which were then open to the retainers of the great, and especially to a young man of letters, had come in Swift’s way. He himself, it is said, “still believed in the royal pledge for the first prebend that should fall vacant in Westminster or Canterbury,” but this was a hope which had accompanied him ever since he explained constitutional law to King William six years before, and could not be very lively after this long interval.

Thus Swift’s life came to a sudden and complete break. The great household, with its easy and uneasy jumble of patrons and dependents, fell asunder and ceased to be. The younger members of the family were jealous of the last bequest, which put the fame of their distinguished relative into the hands of a stranger, and did their best to set Swift down in his proper place, and to proclaim how much he was the creature of their uncle’s bounty. In the breaking up which followed, there were many curious partings and conjunctions. Why Hester Johnson, to whom Sir William had bequeathed a little independence, should have left her mother’s care and joined her fortunes to those of Mrs. Dingley instead, remains unexplained, unless indeed it was Mrs. Johnson’s second marriage which was the cause, or perhaps some vexation on the part of Lady Giffard—with whom the girl’s mother remained, notwithstanding her marriage—at the liberality of her brother to the child brought up in his house. Mrs. Johnson had other daughters, one of whom Swift saw, and describes favorably, years after. Perhaps Mrs. Dingley and the girl whom he had taught and petted from her childhood had taken Swift’s side in the Giffard-Temple difference, and so got on uneasy terms with the rest of the household, always faithful to my lady. At all events, at the breaking up Hester with her little fortune separated herself from the connection generally, and with her elder friend made an independent new beginning, as Swift also had to do. The fact seems of no particular importance, except that it afforded a reason for Swift’s interference in her affairs, and threw them into a combination which lasted all their lives.

Swift was thirty-one, too old to be beginning his career, yet young enough to turn with eager zest to the unknown, when this catastrophe occurred. Sir William Temple’s secretary and literary executor must have known, one would suppose, many people who could have helped him to promotion, but it would seem as if a kind of irresistible fate impelled him back to his native country, though he did not love it, and forced him to be an Irishman in spite of himself. The only post that came in his way was a chaplaincy, conjoined with a secretaryship, in the suite of the Earl of Berkeley, newly appointed one of the lords justices in Ireland, and just then entering upon his duties. Swift accepted the position in hopes that he should be continued as Lord Berkeley’s secretary, and possibly go with him afterward to more stirring scenes and a larger life, but this expectation was not carried out. Neither was his application—which seems at the moment a somewhat bold one—for the deanery of Derry successful, and all the preferment he succeeded in getting was another Irish living, with a better stipend and in a more favorable position than Kilroot: the parish of Laracor, within twenty miles of Dublin, which, conjoined with a prebend in St. Patrick’s and other small additions, brought him in £200 a year; a small promotion, indeed, yet not a bad income for the place and time. And he was naturally, as Lord Berkeley’s chaplain, in the midst of the finest company that Ireland could boast, one of a court more extended than Sir William Temple’s, yet of a similar description, and affording greater scope for his hitherto undeveloped social qualities. Satire more sportive than mere scorn, yet sometimes savage enough; an elephantine fun, which pleased the age; the puns and quibs in which the men emulated one another; the merry rhymes that pleased the ladies,—seem suddenly to have burst forth in him, throwing an unexpected gleam upon his new sphere.

Swift was always popular with women. He treated them roughly on many occasions, with an arrogance that grew with age, but evidently possessed that charm—a quality by itself and not dependent upon any laws of amiability—which attracts one sex to the other. Lady Berkeley, whom he describes as a woman of “the most easy conversation joined with the truest piety,” and her young daughters were charming and lively companions with whom the chaplain soon found himself at home. And notwithstanding his disappointment with respect to the preferment which Lord Berkeley might have procured for him and did not, it would seem that this period of hanging on at the little Irish court was amusing at least. The lively little picture of the inferior members of a great household which Swift made for the entertainment of the drawing-rooms on the occasion when Mrs. Frances Harris lost her purse, is one of the most vivid and amusing possible.

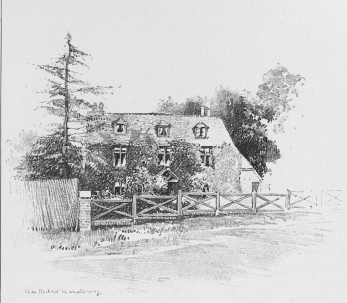

STELLA’S COTTAGE, ON THE BOUNDARY OF THE MOOR PARK ESTATE.

DRAWN BY CHARLES HERBERT WOODBURY, ENGRAVED BY S. DAVIS.

His stay in Ireland at this period lasted about two years, during which he paid repeated visits to his living at Laracor, and made trial of existence there also. The parsonage was in a ruinous condition; the church a miserable barn; the congregation numbered about twenty persons. Many are the tales of the new parson’s arrival there like a thunder-storm, frightening the humble curate and his wife with the arrogant roughness of manner which they, like many others, found afterward covered a great deal of genuine practical kindness. His mode of traveling, his sarcastic rhymes about the places at which he paused on the journey, the careless swing of imperious good and ill humor in which he indulged, contemptuous of everybody’s opinion, have furnished many amusing incidents. One well-known anecdote, which describes him as finding his congregation to consist only of his clerk and beginning the service gravely with, “Dearly beloved Roger,” has found a permanent place among ecclesiastical pleasantries. In all probability it is true; but if not so, it is at least so ben trovato as to be as good as true. There were few claims upon the energies of such a man in such a sphere, and when Lord Berkeley was recalled to England his chaplain went with him. But neither did he find any promotion in London. Up to this time his only literary work had been that wonderful “Battle of the Books,” which had burst like a bombshell into the midst of the squabble of the literati, but which had only as yet been handed about in manuscript, and was therefore known to few. No doubt it was known to various wits and scholars that Sir William Temple’s late secretary and literary executor was a young man of no common promise; but statesmen in general, and the king in particular, sick and worn out with many preoccupations, had no leisure for the claims of the Irish parson. He hung about the Berkeley household, and gravely read out of the book of moral essays which the countess loved those Reflections on a Broomstick which her ladyship found so edifying, and launched upon the world an anonymous pamphlet or two, which he had the pleasure of hearing talked about and attributed to names greater than his own, but made no step toward the advancement for which he longed.

The interest of this visit to England was however as great and told for as much in his life as if it had brought him a bishopric. It determined that long connection and close intercourse in which Swift’s inner history is involved. After he had paid in vain his court to the king, and made various ineffectual attempts to recommend himself in high quarters, he went on a visit to Farnham, where Hester Johnson and Mrs. Dingley had settled after Sir William’s death. Swift found the two women quite undetermined what to do, in an uncomfortable lodging, harassed for money, and without any object in their lives. Most probably he was called to advise as to their future plans, where they should settle and how they were to live, both being entirely inexperienced in the art of independent existence. They had lived together for years, and knew everything about each other: Hester had grown up from childhood under Swift’s eye, his pupil, his favorite and playfellow. She had now, it is true, arrived at an age when other sentiments are supposed to come in. She must have been about twenty, while he was thirty-four. There was no reason in the world why they should not have married then and there, had they so wished. But there seems no appearance or thought of any such desire, and the question was what should the ladies do for the arrangement of their affairs and pleasant occupation of their lives. Farnham being untenable, where should they go? Why not to Ireland, where Hester’s property was—where they would be near their friend, who could help them into society and give them his own companionship as often as he happened to be there? Here is his own account