CHAPTER IV

THE AUTHOR OF “ROBINSON CRUSOE”

THE age of Queen Anne was one which abounded in paradoxes, and loved them. It was an age when England was full of patriotic policy, yet every statesman was a traitor; when tradition was dear, yet revolution practicable; when speech was gross and manners unrefined, yet the laws of literary composition rigid, and correctness the test of poetry. It was full of high ecclesiasticism and strict Puritanism, sometimes united in one person. In it ignorance was most profound, yet learning most considered and prominent. An age when Parson Trulliber was not an unfit representative of the rural clergy, yet the public could be interested in such a recondite pleasantry as the “Battle of the Books,” seems the strangest self-contradiction; yet so it was in this paradoxical age. No man lived who was a more complete paradox than Defoe. His fame is world-wide, yet all that is known of him is one or two of his least productions, and his busy life is ignored in the permanent place in literary history which he has secured. His characteristics, as apart from his conduct, are all those of an honest man, but when that most important part of him is taken into the question it is difficult to pronounce him anything but a knave. His distinguishing literary quality is a minute truthfulness to fact which makes it almost impossible not to take what he says for gospel. But his constant inspiration is fiction, not to say, in some circumstances, falsehood. He spent his life in the highest endeavors that a man can engage in: in the work of persuading and influencing his country, chiefly for her good; and he is remembered by a boy’s book, which is indeed the first of boy’s books, yet not much more. Through these contradictions we must push our way before we can reach to any clear idea of Defoe, the London tradesman who by times composed almost all the newspapers in London, wrote all the pamphlets, had his finger in every pie, and a share in all that was done, yet brought nothing out of it but a damaged reputation and an unhonored end.

It is curious that something of a similar fate should have happened to the other and greater figure, his contemporary, his enemy, in some respects his fellow-laborer, another and more brilliant slave of the government, which in itself had so little that was brilliant,—the great dean whose name has already appeared so often in these sketches. Swift, too, of all his books, is remembered chiefly by the book of the travels of “Gulliver,” which, though full of a satirical purpose unknown to Defoe, has come to rank along with “Robinson Crusoe.” We may say indeed that these two books form a class by themselves, of perennial enchantment for the young, and full of a curious and enthralling illusion which even in age we rarely shake off. Swift rises into bitter and terrible tragedy, while Defoe sinks into matter of fact and commonplace; but the shipwrecked sailor on his desolate island, and the exile at the courts of Lilliput and Brobdingnag, both in the beginnings of their careers hold our imaginations captive, and are as fresh and as powerful to-day as when, the one in keen satire, the other in the legitimate way of business, they first made their appearance in the world. It is a singular link between the men who both did Harley’s dirty work for him, and were subject to a leader so much smaller than themselves.

Daniel Defoe was born in London in 1661, of what would seem to have been a respectable burgher family, only one generation out of the country, which probably was why his father, with yeomen and grazier relations in Northamptonshire, was a butcher in town. The butcher’s name, however, was Foe; and whether the Defoe of his son was a mere pleasantry upon his signature of D. Foe, or whether it embodied an intention of setting up for something better than the tradesman’s monosyllable, is a quite futile question upon which nobody can throw any light. The boy was well educated, according to the capabilities of his kindred, in a school at Newington, probably intended for the sons of comfortable dissenting tradesmen, who were to be devoted to the ministry, with the assistance in some cases of a fund raised for that purpose. The master was good, and if Defoe attained there even the rudiments of the information he afterward showed, and laid claim to, the education must have been excellent indeed. He claims to have known Latin, Spanish, Italian, French, “and could read the Greek,”—which latter is as much as could have been expected had he been the most advanced of scholars,—besides an acquaintance with science, geography, and history not to be surpassed, apparently, by any man of his time. “If I am a blockhead,” he says, “it was nobody’s fault but my own,” his father having “spared nothing” on his education. Much of this information, however, was no doubt picked up in the travels and much knocking about of his early years, of which there is little record. He would seem to have changed his mind about becoming a dissenting minister at an early age, and was probably a youth of somewhat wandering tendencies, as he claims to have been “out” with Monmouth, and does not appear in any recognized occupation till after that unfortunate attempt. He must have been twenty-four when he first becomes visible as a hosier in Cornhill, which seems a very natural and indeed rather superior beginning in life for the son of the butcher in Cripplegate. He laid claim afterward to having been a trader,—not a shopkeeper,—a claim supported more or less from a source not favorable to Defoe, by Oldmixon, who says that his only connection with the trade was that of “peddling to Portugal,” whatever that may mean. We may take it for granted that he had occasions of visiting the Continent in connection, one way or other, with his trade. The volume of advice to shopkeepers which is entitled the “Complete English Tradesman,” written and published in the latter part of his life, though it does not seem to be taken by his biographers in general as any certain indication that he himself made his beginning in a shop, is nevertheless full of curious details of the life of the London shopkeeper of his time, to which class he assuredly belonged. We learn from this curious production that vanity was even more foolish in the eighteenth century than it is now. We are acquainted with sporting shopkeepers who ride to hounds, and with foolish young men who fondly hope to be mistaken for “swells”; but a shopkeeper in a wig and a sword passes the power of imagination. It is a droll example of the fallacy of all our fond retrospections and preference of the good old times to find that in Defoe’s day this was by no means an extraordinary circumstance. “The playhouses and balls,” he says, “are more filled with citizens and young tradesmen than with gentlemen and families of distinction; the shopkeepers wear different garbs than what they were wont to do, are decked out with long wigs and swords, and all the frugal badges of trade are quite disdained and cast aside.”

We may take from this book as an illustration of the habits of the age the following description of a young firm which is clearly on the way to ruin:

They say there are two partners of them, but there had as good be none, for they are never at home or in the shop. One wears a long peruke and a sword, I hear, and you see him often at the ball and at court, but very seldom in his shop, or waiting on his customers; and the other, they say, lies abed till eleven o’clock every day, just comes into the shop and shows himself, then stalks about to the tavern to take a whet, then to the coffee-house to hear the news, comes home to dinner at one, takes a long sleep in his chair after it, and about four o’clock comes into the shop for half an hour or thereabouts, then to the tavern, where he stays till two in the morning, gets drunk, and is led home by the watch, and so lies till eleven again; and thus he walks round like the hand of a dial. And what will it all come to? They’ll certainly break. They can’t hold long.

The account of the shop kept by these two idle masters is equally characteristic.

There is a good stock of goods in it, but there is nobody to serve but a prentice boy or two and an idle journeyman. One finds them all at play together rather than looking out for customers; and when you come to buy, they look as if they did not care whether they showed you anything or no. Then it is a shop always exposed; it is perfectly haunted with thieves and shoplifters. They are nobody but raw boys in it that mind nothing, so that there are more outcries of stop thief! at their door, and more constables fetched to that shop than to all the shops in the street.

The households of the soberer and more sensible members of the craft are also open to grave animadversion. The ladies are too fine; they treat their friends with wine or punch or fine ale, and have their parlors set off with the tea-table and the chocolate-pot, and the silver coffee-pot, and oftentimes an ostentation of plate into the bargain, and they keep “three or four maid servants, nay, sometimes five,” and some a footman besides, “for ’tis an ordinary thing to see the tradesmen and shopkeepers of London keep footmen, as well as the gentlemen. Witness the infinite number of blue liveries which are so common now that they are called the tradesmens’ liveries, and few gentlemen care to give blue to their servants for that very reason.” Of the maids themselves, who ask “six, seven, nay eight pounds per annum” for their services, a terrible account is given in a pamphlet published about 1725, where there is a humorous description in the first person of a young woman who comes to apply for the place of housemaid, evidently maid of all work to the speaker, who lives with his sister, with a man and maid for their household. She is so fine that Defoe himself shows her into the parlor and keeps her company till his sister is ready, thinking her a gentlewoman come to pay a visit. Perhaps it is not Defoe, but, with his usual skill, he makes us think so. All these details bring before us the London of his time. The mercers had their shops in Paternoster Row, “where the spacious shops, back warehouses, skylights, and other conveniences, made on purpose for their trade, are still to be seen,” where “they all grew rich and very seldom any failed or miscarried,” and also in Cornhill, where Defoe’s own establishment was, though there, apparently, business was carried on wholesale. It appears to him that trade is going downhill fast when this order is changed, when Paul’s Churchyard is filled with cane-chair makers, and Cornhill with the meanest of trades, even Cheapside itself, “how is it now filled up with shoemakers, toy shops, and pastry cooks?” Everything is going to destruction, the old trader thinks, shaking his head as he goes through the well-known streets, where once the fine ladies came in their fine coaches standing in two rows; he cannot think but that trade itself is coming to an end when such changes can come to pass. Trade, he says, like vice, has come to a height, and as things decline when they are at their extremes, so trade not only must decline, but does already sensibly decline. It ought to be a comfort to the many timid persons who have lived and prophesied evil since then to hear that Defoe a hundred and fifty years ago had come to this sad conclusion.

He was born into a world he thus describes, into the atmosphere of shops and counting-houses, where the good tradesman lived in the parlor above or behind his shop, and was called with a bell when need was, and was constant at business “from seven in the morning till twelve, and from two to nine at night,” the interval being occupied with dinner; where the appearance of the long, flowing periwig and the sword and the man in blue livery were the danger-signals, and showed that he must break, he could not hold; where the cry of “Stop, thief!” might suddenly get up in the midst of the traffic, and the constable be called to some fainting fine lady who had got a piece of taffeta or a lace in her muff or under her hoop; and where, perhaps the greatest risk of all, a young man of genius, who was but a hosier, might betray himself in a coffee-house and be visited afterward by great personages veiling their lace and embroidery under their cloaks, who wanted a seasonable pamphlet or a newspaper put into the right way. A strange old London, more difficult to put on record in its manners and features than it is to record in pasteboard its outward aspect; where town could be convulsed by a chance broadsheet, and the Government propped or wounded to death by an anonymous essayist; when men of letters were secretaries of state, and other men of letters starved in Grub street, and the masses thanked God they could not read; when a revolution was made for liberty of conscience, yet every office and privilege was barred by a test, and intolerance was the habit of the time. The author of “Robinson Crusoe” must have got all his ideas in the narrow, bustling streets, full of rumors, of wars and commotions, and talk about the scandals of the court, and sight of the finery and license which revolted, yet exercised some strange fascinations upon the sober dissenting tradesmen who had found the sway of Oliver a hard one. He was born the year after the Restoration, and was no doubt carried out of London post-haste with the rest of his family in the early summer when the roads were crowded with wagons and carts full of women, children, and servants, all flying from the plague. The butcher’s little son was but four, but very likely retained a recollection of the crowded ways and strange spectacles of the time; and no doubt he saw, with eyes starting out of their little sockets with excitement and terror, the glare of the great fire which burned down all the haunts of the pestilence and cured London by destroying it. Then, both at school, at Newington, and in the parlor behind the shop, there would be many a grave talk over what was to come of all the wickedness in high places; and when the papist king came to the throne, many discussions as to how much his new-born liberality was good for, and whether there was any safety in trusting to his indulgences and declarations of liberty of conscience. Defoe by this time was old enough to speak his own mind. He had left school at nineteen, and till he was twenty-four there is no appearance that he was doing anything, save, perhaps, picking up notions on trade in general, and as much as a young dissenter could, among his own class, or in the coffee-houses where it was safe, delivering his sentiments upon questions so vital to the welfare of the country. According to his own statement, he had written a pamphlet in 1683 to prove that a Christian power, though popish, was better than the Turk. He was now so bold as to tell the dissenters “he had rather the Church of England should pull our clothes off by fines and forfeitures than the papists should fall both upon the church and the dissenters, and pull our skins off by fire and faggot.” No doubt he was then about in London noticing everything, discoursing largely with a wonderful, long-winded, sober enthusiasm, making every statement that occurred to him look like the most certain truth; talking everywhere, in the coffee-house, at the street corners, down in Cripplegate in the paternal parlor, never silent; a swarthy youth, with quick gray eyes and keen, eager features, and large, loquacious mouth. Better be fined and silenced than let in popery to burn you into the bargain. Better stand fast in all those deprivations and hold your faith in corners, than accept suspicious favor from such a source, and help to bring in again the Jesuit and the Pope. While Penn, with his plausible speech and amiable temper, drew his Quaker brethren into a strange harmony with the courtier’s arts, and presented addresses to James, and accepted his grace, the young tradesman would be pressing his very different argument upon the suspicious somber groups far from St. James’s, where there was no finery, but a great deal of determination. And when in the disturbed and confused wretchedness of the time, no man knowing what was about to happen, but sure that some change must come, young Monmouth set up his hapless standard, could it be Defoe’s own impulse, or the catch of some eddy of feeling into which he had been swept, which carried him off into the ranks of the adventurer? It is said that three of his fellow-students at Newington figure among the victims of the Bloody Assize. Defoe would always be more disposed to talk than fight. He must, we cannot help thinking, have thought it a feeble proceeding to put yourself in the way of getting your head cut off, when you could use it so much more effectually in convincing your fellow-creatures. His mind, ever so ready to slip through every loophole, carried his body off safely out of the clutches of Jeffreys. Probably when he turned up at home against all hope after this unlucky escapade, his friends were too thankful to thrust him into the hosier’s warehouse, where no doubt he would give himself the air of having sold and bought hose all his life.

There is, however, nothing to build any account of his life upon in these earlier years. The revolution filled him with enthusiasm, and King William gained his full and honest support—a support both bold and serviceable, and with nothing in it which was not to his credit. But apparently a man cannot be so good a talker, so active a politician, and follow the rules which he himself laid down for a successful tradesman at the same time. Most likely his mind was never in his hose, and the world was full of so many more exciting matters. Seven years after he had been set up in business he “broke,” and had to fly, though no further than Bristol, apparently, where he made an arrangement with his creditors. He would seem to have failed for the large sum at that time of seventeen thousand pounds, which he honestly exerted himself to pay, and so far succeeded in doing so that he reduced in a few years his debts to five thousand pounds in all; and, what was still more, finding certain of the creditors with whom he had compounded to be poor, after he had paid his composition fully, he made up to them the entire amount of his debt—an unlooked-for and exceptional example of honorable sentiment. Some years later, when Defoe had got into notoriety, and was the object of a great deal of violent criticism, a contemporary gives this fact, on the authority indeed of an anonymous gentleman in a coffee-house only, but it seems to have been generally received as true. The writer was in a company “where I and everybody else were railing at him,” when “the gentleman took us up with this short speech:

“‘Gentlemen,’ said he, ‘I know this Defoe as well as any of you, for I was one of his creditors, compounded with him and discharged him fully. Several years afterward he sent for me, and, though he was clearly discharged, he paid me all the remainder of his debt, voluntarily and of his own accord, and he told me that, as far as God should enable him, he intended to do so with everybody. When he had done he desired me to set my hand to a paper to acknowledge it, which I readily did, and found a great many names to the paper before me, and I think myself bound to own it.’”

This has a suspicious resemblance to Defoe’s own style, but the fact seems to be generally received as true.

Neither his business nor his failure, however, kept him from the active exercise of his literary powers, which he used in the service of King William with what seems to have been a most genuine and hearty sympathy. Pamphlet after pamphlet came from his pen with an influence upon public opinion which it is difficult to estimate nowadays, but which was certainly much greater than any fugitive political publications could have now. He wrote in defense of a standing army, the curious insular prejudice against which was naturally astonishing as well as annoying to the continental prince who had become king of Great Britain. He wrote in support of the war, which to William was a vital necessity, but which England was somewhat slow to see in the same light. And, most effectively of all, he answered the always ready national grumble against foreigners, which was especially angry and thunderous against the Dutchmen, by the triumphant doggerel of “The True-born Englishman,” the first of Defoe’s works which takes a conspicuous place. In this strange and not very refined production he held up to public admiration the pedigree of the race which complained so warmly of every new invasion, and held so high an opinion of itself. “A true-born Englishman ’s a contradiction,” he cries, and sets forth, step by step, the admixtures of new blood which have gone to the formation of the English people—Roman, Saxon, Dane, Norman.

From this amphibious, ill-born mob began

That vain, ill-natured thing, an Englishman.

It is not a very delicate hand which traces these, and many another wave of strange ancestors. “Still the ladies loved the conquerors.” But Defoe’s rude lines went straight to the mark. The public had no objection to a coarse touch when it was effective, and Englishmen are rarely offended by ridicule; never, we may say, when it is home-born. The stroke was so true that the native sense of humor was hit. Perhaps England did not, on account of Defoe’s verses, like the Dutchmen any better, but she acknowledged Tutchin’s seditious assault upon the foreigners to be fully answered, and the universal laugh cleared the air. Eighty thousand copies of this publication were sold, it is said, in the streets, where everybody bought the “lampoon,” which, assailing everybody, gave no individual sting. It also procured for Defoe a personal introduction to the king. Whether it was to this or to his former services that he owed a small appointment he held for some years, it is difficult to say, but evidently he did not serve King William for nothing. In the mean time Defoe resumed his business occupations, and set up a manufactory of pantiles at Tilbury, where he employed a hundred poor laborers, and throve, or seems to have thriven, in his new industry, living in something like luxury, and paying off, as described, his previous debts. His head was full of the projects upon which one of his most successful pamphlets was written, and he recommended many sweeping schemes and made many bold suggestions on all subjects, from the institution of an income tax to that of an academy like the French. It was a period when the air was swarming with schemes, and Defoe was not necessarily original in his suggestions; but his brain was teeming with life and energy, and there is no saying which was absolutely his own thought, and which the thought of others. He was a man to whom ideas came as he was writing, and were flung off into the air, to fly or fall as they might. One thought, one fancy, suggested another. For instance, after arguing long and well in favor of the war with France, which was the object of King William’s life, and the only thing that could save—according to the ideas of his party on the Continent, and eventually of most sound Protestants in England—the Protestant faith, Defoe, with a sudden whimsical perception of certain possibilities on the other side, came out with a pamphlet entitled, “Reasons Against a War with France,” which was founded on the suggestion that a war with Spain instead would be very profitable, and that the Spanish Indies were a booty well worth having: a sudden dash into new fields which must have brought up the public which he had persuaded to fight France with a certain gasp of breathless inability to follow this rapid reasoner in the instantaneous change of front, which meant no real change of opinion, but only the flash of a sudden happy thought.

When William died, however, and the times changed, the High Church came back with Anne into a potency which had been impossible in the unsympathetic reign of that Dutchman. Defoe had written some time before against the practice of occasional conformity; that is, the device by which dissenters managed to hold public offices in despite of existing tests, by kneeling now and then at the altars of the established church, and receiving the communion there. Defoe took the highest view of principle in this respect, and denounced the nonconformists who thus secured office to themselves by the sacrifice of their consciences, “bowing in the House of Rimmon.” There seems no reason, in fact, why a moderate dissenter should not do this, except that any religious duty specially performed for the sake of a secular benefit is always suspect and odious. Yet the obvious argument that a man who could reconcile it with his conscience to attend the worship of the church should not be a dissenter, was unquestionably sound and unassailable in point of logic. Defoe had deeply offended the dissenters, to whom he himself belonged, by his protest; but this did not prevent him from rushing into print in defense of the expedient of occasional conformity as soon as it was threatened from the other side. There is little difficulty in following the action of his mind in such a question. It was wrong and a deflection from the highest point of duty to sacrifice one’s conscience, even occasionally, for the sake of office; but, on the other hand, it was equally wrong to abolish an expedient which broke the severity of the test, and made life possible to the nonconforming classes. The views were contradictory, yet both were true, and it was his nature to see both sides with most impartial good sense, while he felt it to be, if a breach of external consistency, no wrong to defend or assail one side or the other, as might seem most necessary. He allowed himself so complete a license on this point that it is curious he should be found the public champion of the higher duty. No doubt his utterance to his dissenting brethren on that question was to himself no reason why he should not defend their right to use the expedient if they had a mind. But this is too fine a distinction for the general intelligence.

The discussions on this subject were the occasion of one of the most striking episodes in his life. When the bill against occasional conformity was introduced, to the delight of the High Church party, from the queen downward, and when the air began to buzz around him with the bluster, hitherto subdued by circumstances, of the reviving party, who would have made short work with the dissenters had their power been equal to their will, a grimly humorous perception of the capabilities of the occasion seems to have seized Defoe. Notwithstanding that he had angered all the sects by his plain speaking, he was a dissenter born, and there is no such way of reconverting a stray Israelite as to hear the Philistines blaspheme. He seized upon the extremest views of the high-fliers with characteristic insight, and, with a keen consciousness of the power of his weapon, used it remorselessly. The “Shortest Way to Deal with Dissenters” is a grave and elaborate statement of the wild threats and violent talk in which, in the intoxication of newly acquired power, the partizans of the church indulged, with noise and exaggeration proportioned to the self-suppression which had been forced upon them by the panic of a papal restoration under James, and by the domination of the more moderate party during William’s unsympathetic reign. They were now at the top of the wave, and could brandish their swords in the eyes of their adversaries. Their talk in some of their public utterances was as bloodthirsty as if they intended a St. Bartholomew. Defoe took up this frenzied babble, and put it into the form of a grave and practical proposal. As serious as was Swift when he proposed to utilize the superabundant babies of the poor by eating them, Defoe propounded the easy way to get rid of the dissenters and the necessity of settling this question forever. “Shall any law be given to such wild creatures? Some beasts are for sport, and the huntsman gives them advantages of ground, but some are knocked on the head by all possible ways of violence and surprise.” He says:

’T is vain to trifle in this matter. The light, foolish handling of them by mulcts, fines, etc., ’t is their glory and their advantage. If the gallows instead of the counter, and the galleys instead of the fines, were the reward of going to a conventicle to preach or to hear, there would not be so many sufferers. The spirit of martyrdom is over. They that will go to church to be chosen sheriffs and mayors would go to forty churches rather than be hanged. If one severe law were made and punctually executed, that whoever was found at a conventicle should be banished, the nation and the preacher be hanged, we should see an end of the tale. They would all come to church, and one age would make us all one again.

To talk of 5s. a month for not coming to this sacrament, and 1s. per week for not coming to church, this is such a way of converting people as never was known. This is selling them a liberty to transgress for so much money. If it be not a crime, why don’t we give them full license? And if it be, no price ought to compound for committing it, for that is selling a liberty to people to sin against God and the government.

If it be a crime of the highest consequence, both against the peace and welfare of the nation, the glory of God, the good of the church, and the happiness of the soul, let us rank it among capital offences, and let it receive a punishment in proportion to it.

We hang men for trifles and banish them for things not worth naming. But an offence against God and the church, against the welfare of the world, and the dignity of religion shall be bought off for 5s.—this is such a shame to a Christian Government that ’tis with regret I transmit it to posterity.

If men sin against God, affront his ordinances, rebel against his church, and disobey the precepts of their superiors, let them suffer as such capital crimes deserve: so will religion flourish, and this divided nation be once again united.... I am not supposing that all the dissenters in England should be hanged or banished, but as in cases of rebellions and insurrections, if a few of the ringleaders suffer, the multitude are dismissed; so a few obstinate people being bad examples, there’s no doubt but the severity of the law would find a stop in the compliance of the multitude.

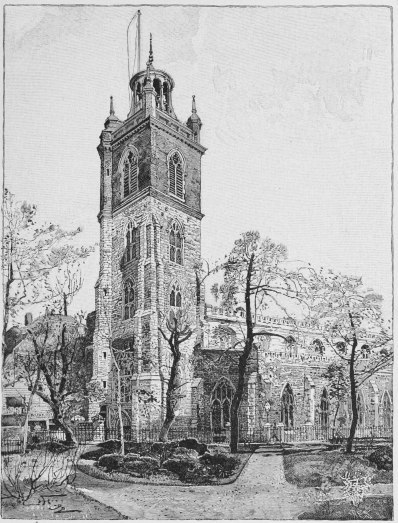

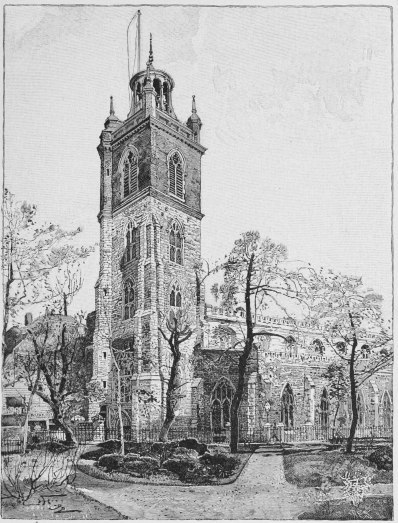

CHURCH OF ST. GILES, CRIPPLEGATE,

WHERE DEFOE IS SUPPOSED TO HAVE BEEN BAPTIZED.

DRAWN BY HARRY FENN. ENGRAVED BY H. E. SYLVESTER.

The reader will perceive by what a serious argument the hot-headed fanatic was betrayed and the wiser public put upon their guard. The mirror thus held up to nature, with a grotesque twist in it which made the likeness bewildering, gave London such a sensation as she had not felt for many a day. The wildest excitement arose. At first all parties in the shock of surprise took it for genuine. “The wisest churchmen in the nation were deceived by i