IV

The Restoration

THE LONDON OF CHARLES II AND OF MR. SAMUEL PEPYS

“We can’t go for a drive to-day before the ‘magic’ begins,” said Betty ruefully on the following Saturday,—a day of pouring rain.

“No. But how lucky that the rain won’t interfere with our visit to the London of Charles the Second,” Godmother returned.

“Is that what we’re going to see to-day? Oh, do let’s go at once, Godmother,” was Betty’s eager reply.

“Wait a little. I’m going to give you a short history examination first, to make sure that you will understand what we see, when we do see it. Elizabeth was reigning when we last went to old London. Who was the next king?”

“Her cousin James the First, the son of Mary, Queen of Scots,” returned Betty promptly. “We’ve just had it in the History class,” she added, to explain her readiness.

“And then?”

“His son, Charles the First. And he was beheaded, and then Cromwell ruled and was called the Protector, and when he died, the people wanted a king again, so they sent for Charles the First’s son from abroad, and he was crowned, and that was called the Restoration,” said Betty very fluently.

Godmother nodded. “The Restoration of course meaning the restoring of kings to the English throne. Now Elizabeth died in the year 1603, and Charles the Second was crowned in 1660, so as the London we shall see will only be about sixty years older than it was in the time of Elizabeth, you wouldn’t expect to find it much altered, would you?”

“No. Except that I suppose it will be a little bigger?”

“Yet during the reign of Charles the Second, London was almost completely changed for a reason you will understand presently,” Godmother returned. “Now before we go back to Restoration days, I want to tell you something about a man who lived in London in the time of Charles the Second. His name was Samuel Pepys. He was educated at that St. Paul’s School we talked about when we looked at some of the great schools that had just begun to flourish in the reign of Elizabeth. Afterwards he went to Cambridge, and then for some years he held posts in the Admiralty,—that is the great office in which the affairs of the Navy are managed. We have passed the street he lived in, many times on our journeys to London Bridge. It is called Seething Lane, and is close to the bridge, and not far from the Monument.”

“I remember seeing it,” Betty answered.

“Well, he was not a great man, though he was industrious and did his work well. He was vain and stingy, and had a great many petty faults, though on the whole he was lovable and kind-hearted. But we can never think of the days of Charles the Second without thinking of Samuel Pepys, and I’ll tell you why. He had the habit of keeping a diary, and that diary, now printed, is one of the most interesting and amusing books you can imagine. It is also very valuable, because as Pepys was a great gossip, and described everything he did, and everything he saw, and every place he went to, very fully, we seem to know the life of London in his day almost as though we had lived it ourselves.”

“Shall we see him?” asked Betty with interest.

“We are sure to. He went a great deal to the Palace of Whitehall, so perhaps we shall meet him there. Anyhow I can’t imagine going to London any time between 1660 and 1670 without seeing Samuel Pepys. I think it is he who must take us back to Restoration London.”

Godmother went to the Cabinet where the magic talismans were kept, and took out a book. “Here is his ‘Diary,’ Shut your eyes, and I’ll read you what he wrote in it one May, two hundred and sixty years ago. He is recording in his ‘Diary’ how he spent that day, now so far in the past.

“‘To Westminster. In the way meeting many milkmaids with their garlands upon their pails, dancing with a fiddler before them, and saw pretty Nelly standing at her lodging door.... She seemed a mighty pretty creature.’”

“Who was ‘pretty Nelly’?” asked Betty, holding the book which Godmother put in her hand in the special “magic” way.

“You will see her if you look now.”

Betty’s eyes flew open upon a charming scene.

In place of the ordinary-looking street of Drury Lane, leading at one end into the Strand, she saw a road lined with gabled dwellings, rather like the old houses still left over Staple Inn in Holborn. The houses were not very close together, and slips of garden with trees in them, gave the “lane” a countrified look. A group of girls wearing muslin caps, short skirts and frilled aprons, and carrying milk-pails slung from their shoulders, came dancing down the road to the music played on a fiddle by a man who walked in front of them. From the milk-pails hung garlands of bluebells and cowslips, and some of the girls carried on their heads instead of pails, little pyramids of silver plates adorned with ribbons and flowers.

Opposite to where Betty and her godmother found themselves standing, leaning in the door of one of the gabled houses, was a pretty, merry-looking little creature, who had evidently only just got up, for she wore a flowered bed-jacket over her short skirt, and a night-cap trimmed with pink ribbons.

“That’s ‘pretty witty Nelly,’” said Godmother. “Nell Gwynne, the famous actress. She often plays at Drury Lane Theatre, lower down the road, and the King greatly admires her.”

“Why, there was a play acted in London not very long ago called Sweet Nell of Old Drury, wasn’t there?” Betty exclaimed. “Mother was talking about it the other day.”

“Yes, a modern play with ‘sweet Nell’ as heroine. Well, there she is. And this is ‘Old Drury’ where she lives.”

Just at the moment, the milkmaids and the fiddler stopped before Nell Gwynne’s house, and began to sing.

“London, to thee I do present

The merry month of May”—

Betty heard these words, but the rest of the song was drowned by the loud music of the fiddle, and the laughter of the girls, in which the charming little actress joined as they came crowding round her to take the coins she distributed right and left.

“If you look round,” said Godmother, “you will see Samuel Pepys, who is a great admirer of pretty Nelly, watching this little scene.”

Betty turned her head, and saw a fat-faced, good-natured, rather conceited-looking man grandly dressed in a black satin coat with silver buttons, huge sleeves made of fine white lawn, a lace cravat, and a wig with long curls. A sword in a scabbard hung at his side, and he carried a tall gold-mounted cane.

“He is very gorgeous because he is going on to Court—to the Palace of Whitehall,” said Godmother. “But we will follow the milkmaids to the Maypole.”

“The Maypole? How lovely!” Betty exclaimed. “Where is it?”

“Quite close. In the Strand. You know the church called St. Mary-le-Strand? It is the first of the two churches that stand in the middle of the road as you go up the Strand from Charing Cross. Well, just in front of that church, we shall find the Maypole. You can hear the shouts of the people now.”

In a minute or two they were in the Strand, and there, in the middle of the road, with long coloured streamers hanging from its summit, stood an enormously tall pole wreathed with flowers, round which with laughter and shouting, men and girls were dancing. Some of the boys had garters with bells round their knee-breeches, and nearly all of them were waving handkerchiefs. The whole street was crowded with noisy, merry-making people, and one boy in particular, standing on a high wooden stool close to the Maypole, seemed to be directing the dance.

“He is the May-Lord, and he arranges the fun,” Godmother said. “Listen to what he is reciting.”

“Up then, I say, both young and old,

Both man and maid a-Maying,

With drums and guns that bounce along

And merry tabor playing!

Which to prolong. God save our King,

And send his country peace,

And root out treason from the land!

And so, my friends, I cease.”

“London is very gay,” Betty remarked as they walked down the Strand towards Whitehall, passing groups of merry-makers on the way. “But it looks just the same as it did in Elizabeth’s day,” she added, glancing from the line of stately mansions on the left, with wide stretches of the river visible between them, to the fields and gardens on the right of the Strand. “The people wear different sort of clothes now, but the town hasn’t altered much, has it?”

“No. We are in the early years of Charles the Second’s reign as yet, and London is as full of gaiety as a few years ago it was dull and gloomy, when the Puritan party was powerful, Cromwell ruled, and all amusements were forbidden. Now the theatres have been reopened, and all the old sports and pastimes of the people have been revived.”

“Then there will be acting going on again in those funny theatres we saw in Southwark?”

“Yes, but these are already falling out of fashion, and will disappear, because finer play-houses are being built on this side of the river. Drury Lane Theatre is one of them.”

“I went there to a pantomime last Christmas,” Betty remarked. “But of course it’s quite a different building now, in our time, isn’t it?”

“There have been three Drury Lane theatres since the one in which Nell Gwynne plays now. You went to the fourth building on the same spot.... Now we’re at the end of the Strand and I’m just going to let you have a glimpse of Whitehall Palace which last time we saw only from the water. Look at that beautiful monument in the middle of the road, just where in our time, stands the statue of Charles the First on horseback. That’s the last of the thirteen crosses put up by Edward the First to mark the place where his wife’s body rested when it was brought from Nottinghamshire to be buried in Westminster Abbey.”

“It’s in Charing Cross Station yard now, isn’t it?” Betty asked.

“Not that one. The monument outside the station in our day, is only a copy of the cross you are looking at. I needn’t tell you that when it was first set up, long, long ago in Edward the First’s time, this place was all country with a tiny hamlet called Cherringe surrounded by fields and woods, where we are standing....

“Now look down the road, remembering that if we were in our own day we should have our backs to Trafalgar Square and our faces towards Westminster. On our left we should see, first shops and houses, and then big buildings all the way down to the Houses of Parliament. On our right, there would be the Horse Guards and a line of Government Offices with St. James’s Park behind them.”

But on what a different scene Betty looked! The whole of the space stretching between the river (which she could see gleaming on her left) and St. James’s Park in full view on her right, was covered with houses, separated from one another by gardens and lawns, but all belonging to, and part of, the Palace of Whitehall. Right through the midst of this great plot of buildings, ran a public road, over-arched by two fine gateways at some long distance apart.

“You remember I told you that Henry the Eighth was the first king to live in this palace?” said Godmother. “He moved here, you remember, from the old Palace of Westminster when Cardinal Wolsey, to whom it originally belonged, fell into disgrace, and had to give it up to him. Henry invited the German painter Holbein, to live at Whitehall, and began a famous collection of pictures here. It was Henry the Eighth also who built many of the houses you see now. They are all part of the Palace. You know that this was one of Queen Elizabeth’s many homes, because you saw her land from the river over there on the left. Now look in the opposite direction. Do you see that great open space on the right? It is called the Tilt Yard, and you have walked through it many times—as it is now in our own day, I mean.”

“Have I? What is it now?” Betty asked.

She was puzzled, for the whole place looked so different from the Whitehall she knew.

“The Horse Guards Parade. The great open space at the end of St. James’s Park, you know. It was there that Queen Elizabeth with her Maids of Honour sat to watch one of the masques she liked so much. It was a sort of masque and tournament combined. The gallery in which she was seated, was called The Fortresse of Perfect Beauty, and a company of splendidly-dressed knights stormed it by shooting sweetly-scented powder and perfumes at it. Then another company of knights calling themselves ‘The Defenders of Beauty’ met the enemy in a mock fight, and defeated them.”

“That was when she was young and beautiful, I suppose?” Betty said. “She was quite old when we saw her.”

“Yes. She was young at the time of that particular masque, but she kept her love for acting and for dancing almost to the day of her death.”

“Did she die here?”

“She died at her palace at Richmond, but her body was borne on a funeral barge down the river there, and here in Whitehall it lay in state till she was buried in the Abbey yonder. Then came James the First, and not content with this great palace, he planned to build a new one! Do you remember I told you of an artist called Inigo Jones who designed beautiful scenery for the masques in this reign? Well, he was also an architect, and he made a plan for a wonderful new palace, and actually began to build it. There is the little bit he finished.” Godmother pointed to a stately house on the left.

“Why, I remember that! It’s in Whitehall now. Opposite the Horse Guards.”

“It is, and it’s all that’s left of Whitehall Palace in our own day. The dream of a new palace remained a dream, for that’s all of it that was ever built, and was only a tiny part of what Inigo Jones meant to do. But it remains to our day, and I never pass it without thinking of the tragedy that happened there.”

“What tragedy?”

“Don’t you remember that it was there on a scaffold put up outside that second window at this end, that James’s son, Charles the First, was executed?”

“I’d forgotten,” Betty said, looking with interest at the window Godmother pointed out. “James little thought he was having the very place built where his poor son was to die, did he?” she added after a moment. “Then did Oliver Cromwell come to live at Whitehall?” she asked presently.

“Yes, and he took all the royal apartments for himself and lived in state with the poet Milton as his secretary. Here he died, only two or three years ago, and now the Palace is filled to overflowing with the great Court of the present King. Let us walk across to the river front.”

They passed through many gardens and courts surrounded by houses built in the Elizabethan fashion, with gabled roofs, and timbered fronts, till they came to a long stone building facing the river, but divided from it by a pretty garden.

“This is called the Stone Gallery,” said Godmother, “and here two of the beauties of the Court have their apartments. One is Lady Castlemaine, and the other the Duchess of Portsmouth.”

“What a lovely place to live in!” Betty exclaimed. “Overlooking this garden and the beautiful river.”

“It has its disadvantages,” Godmother remarked drily. “Sometimes the river floods the lower rooms at high tide. Only yesterday, for instance, when Lady Castlemaine had invited the King to dine with her, the cook came to tell her that the water had put the fire out in the kitchen.”

Betty laughed. “What did she do?”

“Pepys wrote it all down in his diary this morning, so we know. He tells us that Lady Castlemaine exclaimed, ‘Zounds!’ (a favourite word in these Restoration days), ‘you may burn the palace, down but the beef must be roasted!’ ‘So,’ the ‘Diary’ goes on, ‘it was carried to Mrs. Sarah’s husband, and there roasted,’ ‘Mrs. Sarah’ being the housekeeper to one of Mr. Pepys’s friends.

CHARLES I.

“Those are the Queen’s rooms,” Godmother went on, pointing to a row of windows some distance from the Stone Gallery, but like it, facing the river. “Poor Catherine! she is very much neglected, and these Court ladies’ apartments are much grander and better furnished than hers.”

“Queen Catherine?” echoed Betty.

“Catherine of Braganza. She is a Portuguese lady whom King Charles has lately married.”

“Shall we see the King?” Betty asked.

“We may have a glimpse of him in a moment. He is far from being a good king, you know, though he is good-natured and witty, and easy to get on with. He hates to be troubled with business, and doesn’t care about the honour or welfare of his country so long as he has plenty of money, and can spend his time in amusement. He lives here in the greatest luxury, surrounded by frivolous courtiers. One of them wrote some amusing lines about him the other day which he had the audacity to fasten up on the door of the King’s bedroom:

‘Here lies our sovereign lord, the King

Whose word no man relies on.

He never said a foolish thing

And never did a wise one.’

And that very well describes Charles the Second. Now pay great attention to the Banqueting Hall, not long ago built by Inigo Jones, because it’s the only bit of all this scene that you will be able to look at when we are in our own day once more. There, wonderful banquets are held on a magnificent scale, when the King entertains ambassadors from foreign courts. And now let us stroll into St. James’s Park. The King has recently laid it out as part of the grounds of his palace, though the public is allowed to enter it.”

“It’s quite different now,” said Betty, gazing at a long straight canal which instead of the well-known winding lake, ran from end to end of the Park. “Look at those stiff avenues of trees on each side of the water! It isn’t a bit like an English park.”

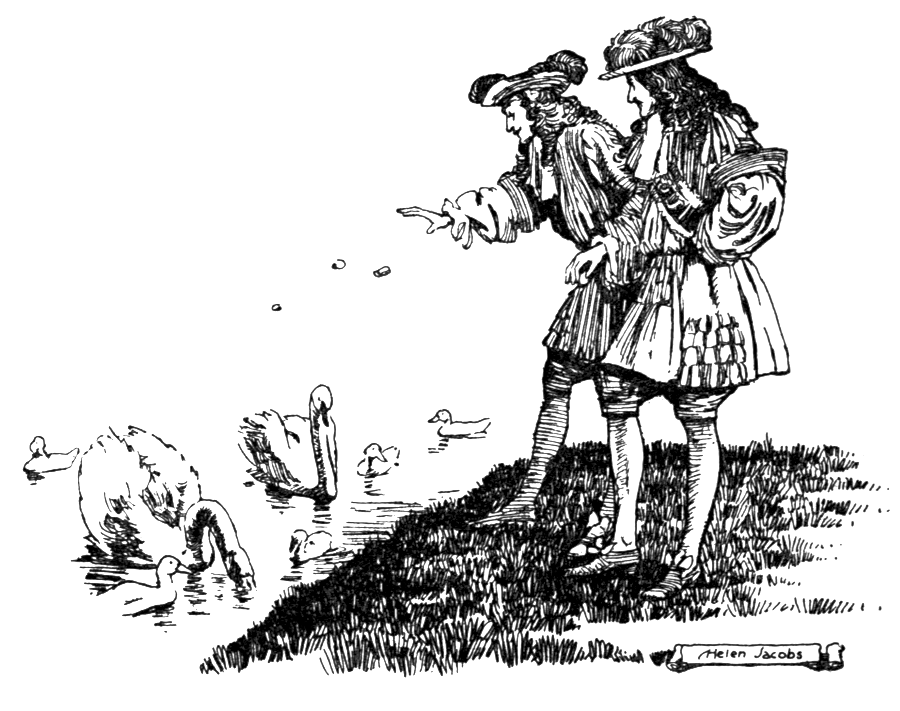

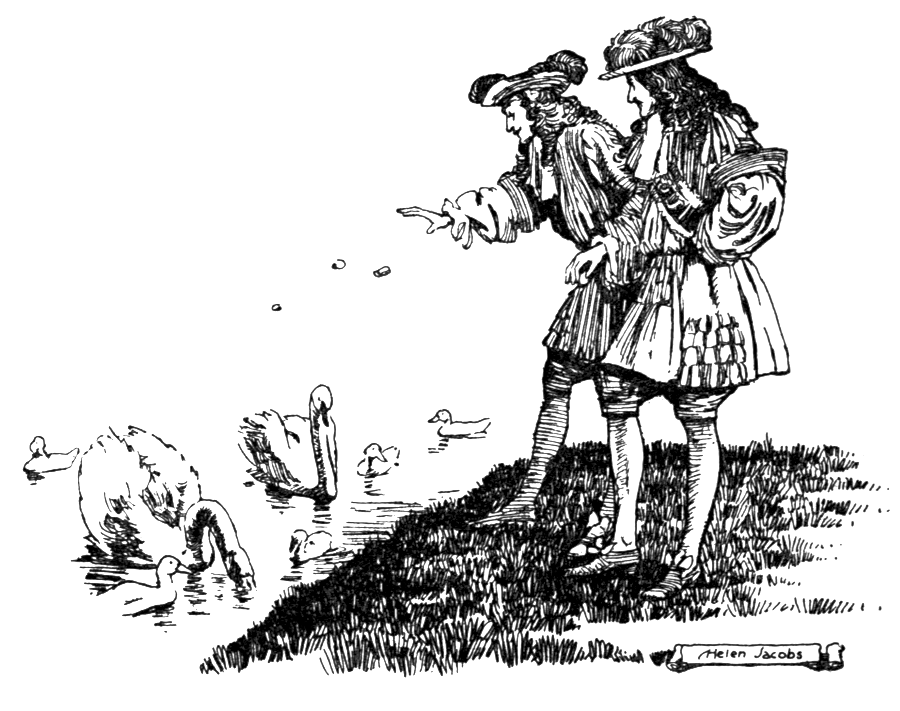

“No. That’s because while he was in exile, Charles lived in Holland, and became very fond of the Dutch style of formal gardening, which he has copied here. But I’ll show you something that will be familiar to you. Do you see that little island with the ducks and wild-fowl swimming near it. The water birds that live in St. James’s Park now, and had such a beautiful home before the Park was made ugly with sheds during the war, are the descendants of those very birds belonging to Charles the Second. He often comes here quite unattended to feed them.”

“Godmother, I do believe he’s there now!” Betty exclaimed, pointing to a dark, heavy-faced man with a long curling wig, throwing bread to the ducks, as with loud quacks they came swimming towards him. “He’s dressed like the pictures I’ve seen of Charles the Second anyhow.”

“Yes, that’s the King. And the man beside him, with the splendid satin coat and the wide hat with the curling red feather, is the Duke of Rochester, one of his favourites. See how they’re laughing together!”

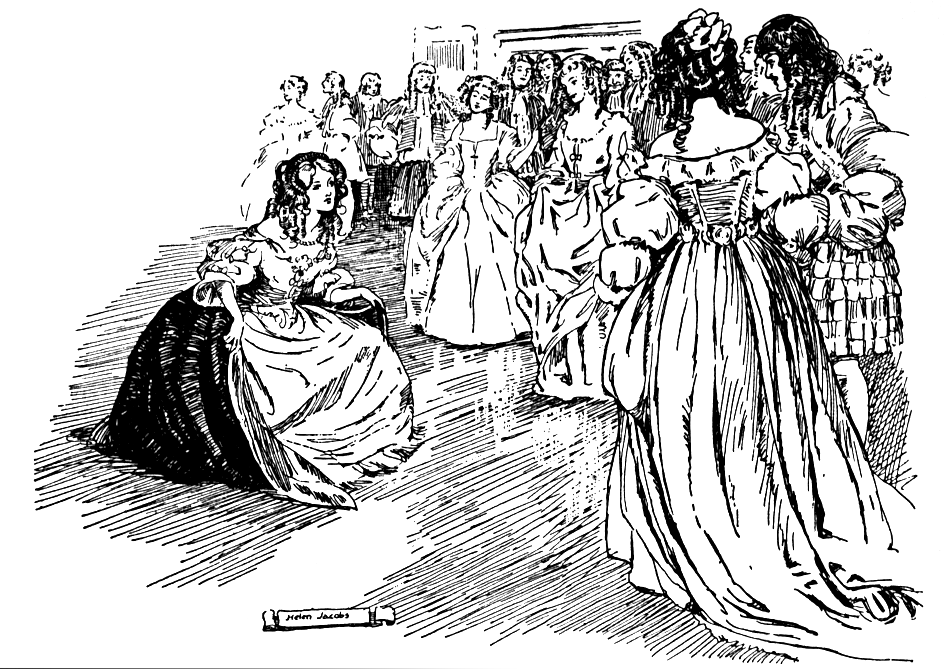

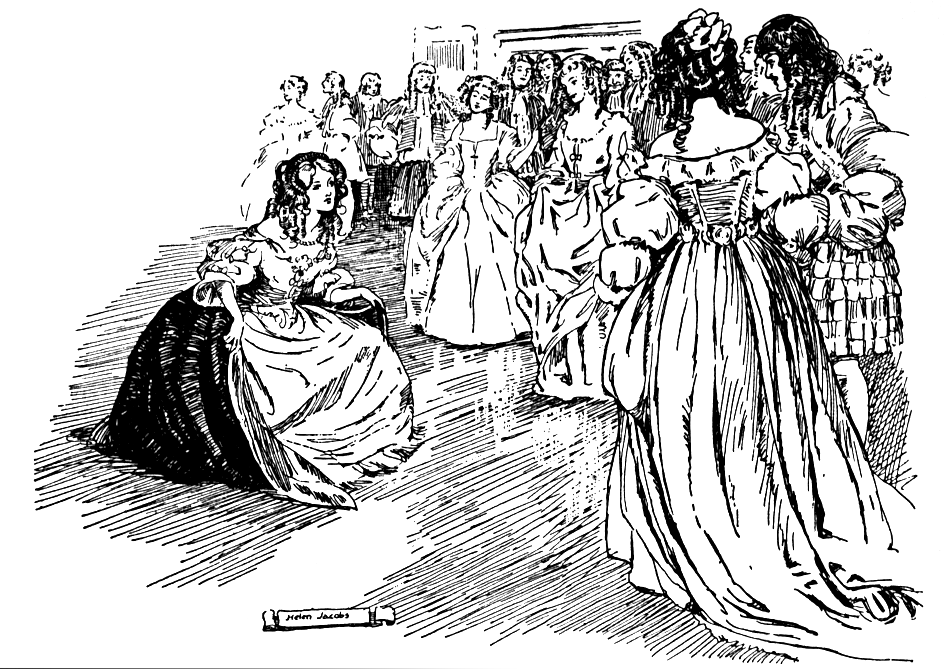

One moment Betty saw them thus. Then, the whole scene vanished, and instead of standing in the sunlight in the Park under the trees, she found herself in a gorgeous ball-room, lighted by hundreds of wax candles in sconces against the gilded walls. It was filled with men and women beautifully dressed in the costume of Stuart days, which Betty recognized from portraits she had seen of people belonging to Restoration times. The men carried in their hands big felt hats with sweeping feathers, and they all wore wigs with long curls to the shoulders, while the ladies were gay in rich brocades, and sparkled with jewels. A buzz of talk and laughter almost drowned the music played in a gallery above.

“They are waiting for the King and Queen to come in and open the ball,” Godmother said. “Do you see Mr. Pepys in that corner under the musicians’ gallery? He is talking to his friend Mr. Povey, a member of Parliament, who has brought him here to-night to see this particular ball.”

Presently the doors at one end of the room were flung open and the King, leading the Queen by the hand, entered, followed by his brother, the Duke of York, who led the Duchess.

Then the dancing began. At first it was a stately dance called the Brantle, in which the couples followed one another round the room, keeping step to the music.

“That’s the Duke of Monmouth bowing low to Lady Castlemaine,” Godmother said, seeing that Betty was watching a very handsome young man whose partner was a pretty lady in a wonderful gown of blue and silver. “You will read about his tragic end in your history. But now he is young and gay and in high favour with the King.”

“Look! the King and a lady are dancing alone!” cried Betty. “Doesn’t he dance well?”

“That dance is called a Coranto. You see that every one in the room stands up when the King dances. There! He is calling to the musicians for a merrier tune, and now we shall see a country dance, very different from these stately measures.”

In a moment or two indeed the whole gay throng was jigging to a lively air such as Betty had heard the fiddler play for the milkmaids in Drury Lane.

“It’s a Morris dance,” she exclaimed. “We learn it at school.”

“Yes, there’s a fashion in our day to bring back the old-fashioned country dances that were common in England two or three hundred years ago. See how the King is enjoying it,” she added. “You can understand why, in spite of his failings as a ruler, he is so popular with his subjects. They love his free and easy ways, and his lazy good-nature.”

“I suppose Mr. Pepys will write about this ball?” Betty suggested.

THE KING ENTERED, LEADING THE QUEEN BY THE HAND

“Oh yes. The ‘Diary’ says, ‘Mr. Povey and I to Whitehall: he taking me thither on purpose to carry me into the ball this night before the King,’ and a few lines further on we read, ‘Then to country dances; the King leading the first, which he called for.’”

“And we’ve actually seen him do it!” Betty exclaimed.

But almost before she finished speaking, a thick mist swallowed up the ball-room with its sparkling lights and its whirling men and women.... The sun was shining, and they were once more in the open air.

“We are in the Chepe now,” Betty said, recognizing it immediately, for it had scarcely changed at all since the reign of Elizabeth.

It was decorated now in honour of May Day. Scarlet hangings draped the front of the houses not only of the market-place itself, but of those in the narrow streets leading from it. Wood Street, a dirty dark lane overhung by its picturesque wooden dwellings, was especially gay, Betty noticed. It was full of life and bustle. At every doorway people stood talking and laughing, and where the top stories almost met overhead, she noticed children leaning from the windows to exchange handfuls of flowers with little opposite neighbours who could reach them easily.

“Now,” said Godmother, “that we have seen London gay and merry on this May Day in the early part of Charles the Second’s reign, I’m afraid you must have just a glimpse of the city a few years later in terrible trouble. Shut your eyes.”

Betty obeyed, and when after a moment Godmother said, “Open them,” she looked round her in horror. They were standing on the same spot in the Chepe, for there was the entrance to Wood Street, just opposite. But what was this terrible change? The Chepe was silent and deserted. Grass was growing between the cobblestones with which it was paved, and the only creature in sight, was a man walking beside a covered cart ringing a bell. What was he repeating in that hoarse voice of his? She listened and with a shudder heard the words, “Bring out your dead! Bring out your dead!”

“We will walk a few steps down Wood Street,” Godmother said.

Betty followed her along the narrow lane. The doors of the houses were all closed. No groups of gossiping people stood there now, and there were no laughing children high above, throwing flowers to one another. On almost every other door Betty saw a red cross drawn in chalk, and beneath it was scrawled God have mercie upon us. The air was full of the sound of tolling bells.

“Oh! how dreadful!” she cried. But the words were uttered in Godmother’s parlour, and she was thankful to be whisked so suddenly into her own day.

“The Plague was in London then, I suppose?” she asked.

“Yes. A moment ago, we were in the year 1665, and the Chepe, and Wood Street, showed you the terrible state of things that existed then all over the city. Nearly all the richer people had left London by the time we had that glimpse of only one of the streets in which the disease raged. The Court had moved from Whitehall; most of the clergy had run away. So had many of the doctors. The people died by thousands, and still in those narrow dirty streets the plague spread. Trade was at a standstill, and multitudes were starving, and only kept alive by money sent for their relief to the Lord Mayor and the Archbishop and two or three noblemen who bravely refused to desert the city.”

“Did Mr. Pepys go away?” Betty asked with interest.

“No. His work kept him in London nearly all the time, and of course he tells us much about this awful year. Let us look at his ‘Diary.’”

She opened the book which had been responsible for the magic scenes Betty had already beheld, and began to turn the leaves.

“Here,” she said, “on June 7th, 1665, long before the terrible disease had reached its height, Mr. Pepys wrote, ‘The hottest day that ever I felt in my life. This day, much against my will, I did in Drury Lane see two or three houses marked with a red cross upon the doors, and Lord have mercy upon us writ there.’ But though Pepys owns that he is often afraid, he keeps quite calm, and does not forget to mention when he puts on new clothes. (He is very vain, you know, and fond of dress.)

“On September 3rd, when the plague was at its height, this is what appears in his ‘Diary’: ‘Up; and put on my coloured silk suit very fine.’ He goes on to say how he dares not put on his new ‘periwigg’ (that is the sort of long curling wig we saw him wearing just now) because he thinks it might hold the infection. Still Mr. Pepys was no coward during this terrible time, and seems to have done what he could to help the poor. Well, we will not linger over the misery of London during that awful year of 1665. A hundred thousand Londoners died of it, and even before it was quite over, another terrible misfortune fell upon the poor city, of which you shall just have a second’s glimpse. Hold this book. Shut your eyes, and think yourself on Bankside in Southwark, near St. Saviour’s Church.”

Betty had no sooner done this, than even before she opened her eyes she was conscious of a fierce glare. Then just for a flashing second she saw on the opposite side of the river, London burning. From the Tower on the right hand, across the river, to St. Paul’s far down on the left, the city was a sheet of flame, and the night sky overhead was deep crimson with the reflected glare!

Before she had time to feel frightened she was in the quiet parlour where Godmother still sat, turning over the leaves of the “Diary.”

“How wonderful, but awful it looked, Godmother! I couldn’t have borne to see it a second longer. What does it say about it in Mr. Pepys’s book?”

“He describes the Fire very fully. He tells how at three o’clock on Sunday morning, Jane, the maid, called him up, saying there was a big blaze near them. But it is some hours later before he understands that this is something more than an ordinary fire. Then he goes to the Tower, and from one of the roofs there, sees all the wharves and quays and the houses in Thames Street (Chaucer’s street, you remember,) in a blaze. The houses on London Bridge were beginning to burn also. He tells of the scenes on the river where the people were rushing from their blazing houses on the bank and crowding into boats carrying all they could snatch up in their flight, ‘poor people staying in their houses as long as till the very fire touched them,’ he writes, ‘and then running into boats, or clambering from one pair of stairs by the waterside to another. And among other things, the poor pigeons, I perceived were loth to leave their houses, but hovered about the windows and balconys till they burned their wings and fell down.’”

“We went down one of those very stairs on to the quay when we saw the sailor man telling the boys of his travels—in Queen Elizabeth’s days,” interrupted Betty. “And I remember the pigeons were flying about then! Do go on, Godmother.”

“Well, then Pepys goes on to say he takes a boat and rows down the river to Whitehall and informs the King and the Duke of York (afterwards, you know, James the Second) that this fire is very serious. So the King orders him to tell the Lord Mayor to have houses pulled down as fast as he can, to stop the flames, if possible, by makin