V

The Eighteenth Century

THE LONDON OF THE GEORGES AND OF DR. JOHNSON

“To-day we’re going to see London as it was after the Fire!” exclaimed Betty, when she had recovered as usual from her first astonishment and delight at “remembering everything” the moment she saw Godmother. “How are we going to get back this time?”

“Well, there’s a good deal we can see without ‘going back’ at all,” Godmother replied. “Because all that surrounds us every day is London after the Fire. Many buildings exist now, just as they were put up when the city began to rise from its ashes in the latter part of Charles the Second’s reign.”

“Isn’t there to be any ‘magic’ at all to-day, then?” Betty’s voice was full of disappointment.

“Not just yet, at any rate. We are not going back quite so far into the Past this time. Only, in fact, about a hundred and fifty years—to the middle of the eighteenth century.”

“But London must have changed even in that time?”

“It has—enormously. Yet at the same time much remains the same, and I propose to show you first what is left in our own day of the end of the seventeenth and the whole of the eighteenth centuries. It will only be necessary to employ magic in the case of certain places that have altogether vanished from the London of our own time. But before we go any further with or without magic, we must have our usual little history examination. So sit down and collect your thoughts.”

Betty obeyed with a good grace, for she knew she would find all she was about to see, ten times more interesting for not being “in a muddle” about her history.

“When we left London last time,” Godmother began, “Charles the Second was reigning. Who was the next king?”

“James the Second, his brother,” Betty said, after a moment’s thought.

“And then?”

“William and Mary.”

“Why didn’t the son of James the Second come to the throne?”

“Because there was a revolution, and the people chose James the Second’s son-in-law to be king, and he was William of Orange, who was married to James’s daughter, Mary.”

“Very good!” exclaimed Godmother approvingly. “Queen Anne, you remember, Mary’s sister, was the next sovereign. And after her?”

“Let me see. She had no children, so a relation of hers, a German man, was chosen. He was George the First. Then came George the Second, and then——”

“That will do,” Godmother interrupted. “The reign of George the Second brings us to the London we’re going to see to-day, partly, but not altogether by magic. Some of it at least we can see in the course of a walk or drive, for it still exists. Now we’ll have the car and go as usual to London Bridge for a general view of the city that has risen up since the Fire and has been growing bigger and bigger for two hundred and fifty years.”

Half an hour later they were passing the Monument at the entrance to the Bridge, and this time Betty looked up at it with greater interest than ever.

“That marks the place where the Fire began,” she murmured. “How soon afterwards was it built, Godmother?”

“About eight years afterwards. Sir Christopher Wren designed it. He, as I hope you remember, was the great architect who practically rebuilt London. At least so far as great public buildings are concerned. We’ll get out now, and walk to the middle of the bridge.”

“The last time I saw it ‘magically’ the funny pretty houses on it were burning!” Betty said. “I do wish this was the very same bridge,” she added with a sigh.

“Well, at least it’s almost, though not quite in the same place as the one you stood on with Chaucer, and that’s something, isn’t it? But now look right and left, and remembering the London you saw burning, tell me what changes you notice in the kind of buildings you see now. There’s the new St. Paul’s, for instance, and you remember the old one?”

“It’s quite a different sort of church now,” Betty said. “Old St. Paul’s had a spire and pointed roofs and arches instead of that big dome with the ball and cross on the top. All the churches now are different,” she went on, looking from one white steeple to another rising above the houses.

“Yes. You see, don’t you?—that the architecture of London,—that is, the way a building is made—has changed completely. Before the Fire, the churches and most of the other important buildings, were in a style we call Gothic. They had pointed arches, like Westminster Abbey, and if you keep the appearance of the Abbey in mind, you will have a good idea of what Gothic architecture means. See how very different is this new St. Paul’s! It has a dome. In front of it runs a line of pillars supporting a sort of stone triangle. Look at the gallery of columns upon which the dome rests. It is all as different as it can be, from the architecture of the Abbey. Now for the sort of architecture of which the new St. Paul’s is an example, the architects took the ancient Greek temples for their models. Nearly all the architects who lived later than Elizabeth’s time, built in this way, and Christopher Wren and Inigo Jones (who designed the Whitehall Banqueting House, you remember) were two of the men of the seventeenth century who planned their buildings on Grecian models. Now as Wren designed most of the important buildings, we may expect to find London architecture after the Fire, for the most part in this new style. It is called the classical style, and the new St. Paul’s is a good example of it.”

“But all the crowded houses and quays and bridges that we see now weren’t here till much later even, than George the Second’s time, were they?”

“Indeed no, though of course London had grown bigger in the eighteenth century than it was even after the time of the Fire. When we make use of the ‘magic’ presently we’ll just take a glimpse of the City from London Bridge in the eighteenth century. I’ve only brought you here now to get a general view of the new sort of churches.”

“Where are we going now?” Betty asked as they re-entered the car.

“I’m going to take you to see one at least of the four Inns of Court.”

“Inns of Court? What are they?”

“Well, they were founded to be colleges for the study of law, and lawyers still live in them and dine in their halls, and law students have to pass examinations set by the men who govern the Inns. They are all rather close together, round about Fleet Street, which as you know is a continuation of the Strand.”

“This is Fleet Street, isn’t it?” Betty said. “Yes! There’s the monument with the Griffin on it in the middle of the road, outside the Law Courts.”

“And here is the entrance to the Middle Temple, quite close to that monument,” Godmother replied, stopping the car. “The Middle Temple is the name of one of the Inns. The others are the Inner Temple, Lincoln’s Inn and Gray’s Inn. They are all interesting and beautiful, but we shall only have time to look at the two ‘Temples’—Middle and Inner—which are side by side.”

“Oh! what a nice entrance!” Betty said as they passed under an old brick gate and house.

“Yes. That was designed by Christopher Wren just after the Fire.”

“Why is this place called the Temple?” Betty asked, and almost in the same breath, “Oh, Godmother, how pretty it is! Isn’t it wonderful to turn out of the noisy street into this quiet place?”

“That’s one of the surprises of London town,” Godmother said. “It’s full of charming leafy places like this—if you know where to look for them.”

Betty was gazing at the straight-fronted houses enclosing numberless quiet courts,—houses whose bricks were now dark red with age, and from them she looked past a row of big, beautiful trees to where green lawns sloped down to the Embankment with the shining river beyond. She saw that the courts and corridors and gardens, covered a great space between Fleet Street on one hand and the river on the other.

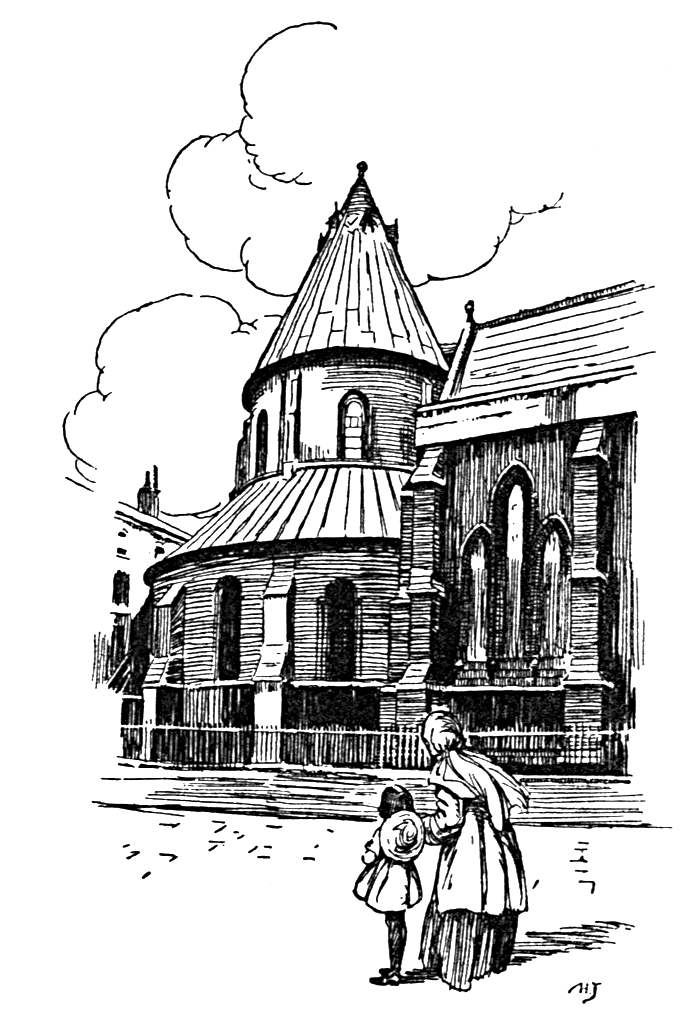

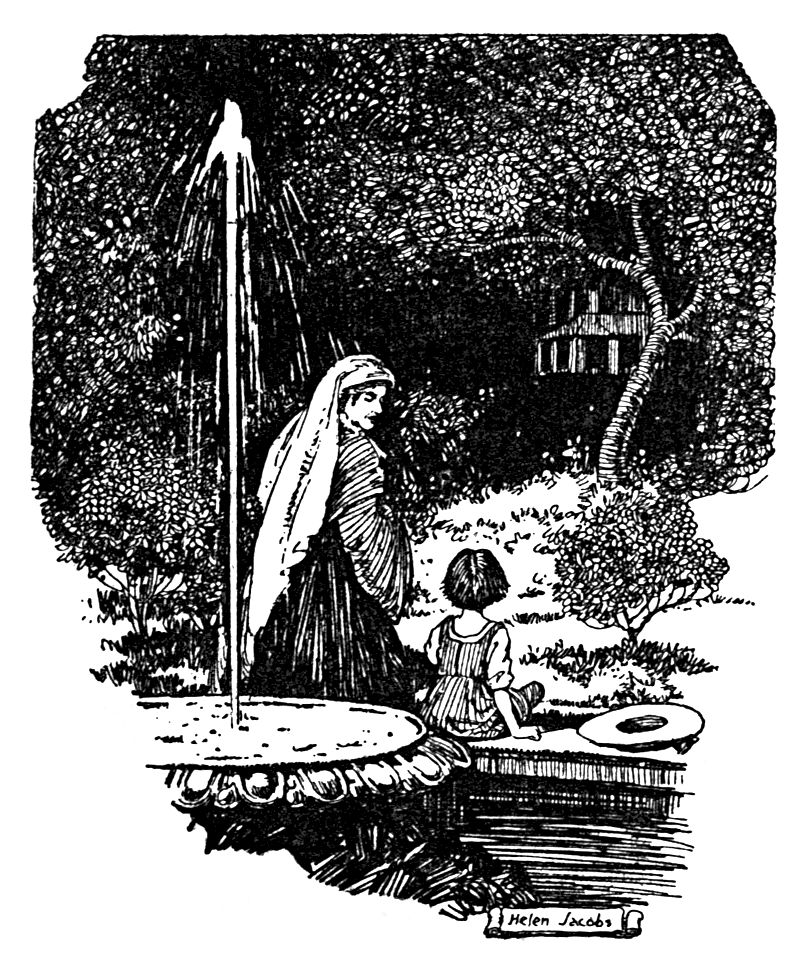

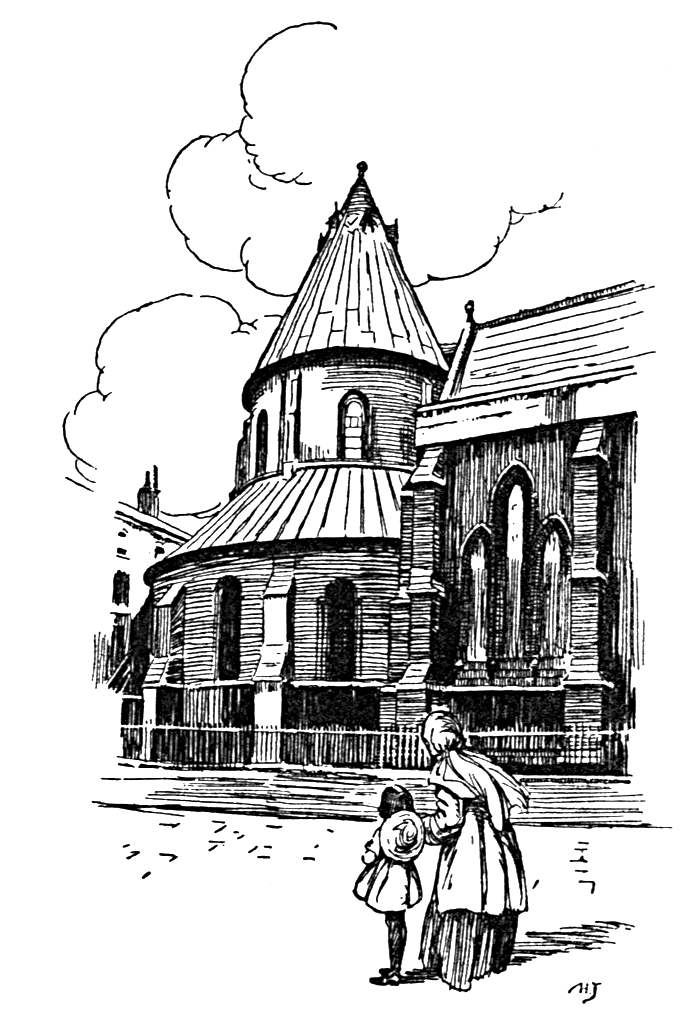

“Let us sit down here under the trees in King’s Bench Walk,” Godmother said, “and I’ll tell you a little about this place. You asked me just now why it was called the Temple. Did you notice the church we’ve just passed—a curious round-shaped church? Well, that was built more than seven hundred years ago, when Henry the Second was king, and knights from every civilized country were going to Palestine to fight in the Crusades. Some of these knights formed themselves into a society called the Templars, because they had sworn to defend the Temple of the Holy Sepulchre at Jerusalem. Well, when the English knights belonging to this great Society, or Order as it was called, came home, they built that church and made it round in shape, in imitation of the Round Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Once upon a time these Knights Templars owned all this ground upon which the lawns and houses before us now stand.”

“But I thought you said this was a place for lawyers?” Betty began.

“So I did, and so it is now, and so it has been ever since the reign of Edward the Third. By that time, the Knights Templars were no longer the good sincere men who had formed the Society a hundred years or so before. They had become rich and proud and greedy of power, and the society was at last brought to an end. The property belonging to it went to the King, and in Edward the Third’s reign, was given to certain lawyers, and has ever since belonged to the profession of the law. But it keeps its old name of the Temple, and so recalls the time when it belonged to the great religious society of the Knights Templars.”

“But none of their houses or buildings are left here now?” Betty said.

“Nothing except the round church which they built seven hundred years ago.”

“And even the houses here now, aren’t so old as the time when the Temple first came to the lawyers, are they? They are quite different from the houses of Dick Whittington’s time, or even Elizabeth’s reign, for instance.”

“Yes. That’s because all these small houses were built after the Fire, which destroyed most of the Temple. Fortunately it didn’t burn the church (the oldest part of it all), nor Middle Temple Hall, which was built in Elizabeth’s reign. We’ll go and look at that Hall now, because besides being beautiful, it’s full of interesting memories.”

They crossed various quiet courtyards till they came in sight of a Hall built of dark red brick and surrounded by the delicate green of trees, with lawns stretching in front of it towards the river.

“That great room,” said Godmother, “has seen some wonderful sights, especially at Christmas time, when feasting and revelry went on within it. You remember the ‘masques’ of Queen Elizabeth’s day? Well, Middle Temple Hall was a favourite place for them, and the Queen herself sometimes came to see them there. You will understand in a moment what a splendid place it was for entertainments.”

And indeed when Betty stood under the oak rafters of the great room, with its stained-glass windows and its wide floor, she could imagine it filled with laughing, dancing people of Elizabethan days, or as it looked when on a platform at one end of it, decked with holly and garlands of ivy, the players acted a masque before the standing crowd that filled the rest of the hall.

“In this very place,” Godmother said, “Twelfth Night was once acted, and it is thought that Shakespeare himself took part in the performance of his own play. I hope the people who dine in it now sometimes think of the folk who feasted and made merry here hundreds of years ago.”

“Is it still the dining-room for the law people, then?”

“Yes, the governors of the Inn, the benchers as they are called, and the students dine here, and by an old custom no student can become a barrister unless he or she has dined a certain fixed number of times in this Hall.”

“She?” echoed Betty.

“Yes, don’t you know that women have lately been allowed to study for the law?” Godmother laughed. “If any of all the famous lawyers now dead, could come back to this place, perhaps of all the changes the one that might most astonish them would be to find girls and women dining—‘keeping commons’ as it is called—in this Hall which for hundreds and hundreds of years has been sacred to men alone.”

“Shakespeare wouldn’t be so very surprised, perhaps?” suggested Betty. “He wasn’t a lawyer, of course. But he would remember writing about Portia.”

Godmother laughed again. “Quite right, Betty. I’m sure he would. And now that you mention Shakespeare, do you remember anything about the Temple in his plays?”

Betty shook her head.

“These are the gardens of Middle Temple,” said Godmother, pointing to the lawns in front of the Hall (on one of which some young men were playing tennis). “It was the same garden that Shakespeare, who knew it well, chose for a famous scene in his play of Henry the Sixth when the party of Lancaster chose the red rose and the party of York the white one for a badge.”

“And then the Wars of the Roses began!” said Betty. “What does Shakespeare say about it?”

“The scene goes like this. The gentlemen who take different sides in the quarrel between the House of York and Lancaster are just coming out of that very building,” Godmother began, pointing to the Hall, “and one of them says:

‘Within the Temple Hall we were too loud:

The garden here is more convenient.’”

“This very garden,” interrupted Betty. “Only I expect it was wilder and had lots of flowers in it then?”

“Evidently there were many rose bushes, for one noble, who is on the side of the Yorkists, says:

‘Let him that is a true born gentleman

And stands upon the honour of his birth

If he suppose that I have pleaded truth

From off this briar pluck a white rose with me.’

Then Somerset, on the side of the Lancastrians, takes up the challenge:

‘Let him that is no coward nor no flatterer

But dare maintain the party of the truth

Pluck a red rose from off this thorn with me.’

So the white and red roses are picked and stuck into the doublets as the sides are taken, and another noble, wise enough to see into the future, says that this quarrel in the Temple Gardens ‘shall send between the red rose and the white, A thousand souls to death and deadly night.’ And so it did, in the dreadful long War of the Roses, as you remember.”

“But, Godmother,” began Betty after a moment, “I thought we were going to be in the eighteenth century to-day, and so far we’ve been talking about much earlier times!”

“So we have! And that’s the worst, or best, of London. When a place like this Temple, is very old, the history of a great many ‘times’ belongs to it. But you’re quite right to remind me that I brought you here because, except for the church, and the Hall, and one or two other buildings, the look of the place as it is now, is much more seventeenth and eighteenth century than anything else, and is ‘mixed up’ as you so often say, with the lives of many interesting eighteenth-century writers, who lived in one or other of the houses enclosing these charming courts. You’ll know, or you ought to know, two of them, if I mention their names. Dr. Johnson and Oliver Goldsmith.”

“I’ve read The Vicar of Wakefield that Goldsmith wrote,” said Betty, “and I’ve heard of Dr. Johnson’s Dictionary—but I don’t know much about him.”

“Yet he’s the man who will help us with our magic journey presently,” Godmother returned. “For the time you may remember that Oliver Goldsmith was one of his friends.”

“Why, there’s his name!” Betty exclaimed as she caught sight of a medallion on the wall of a house in an enclosure called Brick Court.

“That’s where he lived and died, and the tablet is there to commemorate him. He was buried in the churchyard of the Temple Church. Come! I will show you his tombstone. You will, I expect, read Goldsmith’s life when you are older, and find out what a lovable man he was, in spite of many tiresome ways,” she went on as they stood looking down at his grave.

“Perhaps we shall see him when the magic begins?” Betty suggested. “I should love to see him. The Sixth Form acted a scene out of She Stoops to Conquer last term. That’s one of his plays, isn’t it?”

“Yes, and a very charming one. No doubt, as you say, we shall actually see him later on, but we can look at a very amusing picture of him even before the magic begins, in a house I’m going to take you to visit now at once.”

“What house? Who lives there?” asked Betty, turning to take a last glance at the quiet dignified old houses of the Temple before they left it for the noise and bustle of Fleet Street.

“No one now. But a hundred and seventy years ago Dr. Johnson lived there with his wife. It isn’t far from here, so we’ll walk.”

By this time they were standing under the archway at which they had entered the Temple.

“That’s the Law Courts, isn’t it?” Betty asked, pointing to a pile of buildings opposite. “But they’re not old, are they?”

“No. They were built about forty years ago. But near them, are the two other beautiful old Inns I mentioned, Lincoln’s Inn and Gray’s Inn, both of which you must see some day. This part of London is full of buildings connected with the law.

“Now let us walk a little way up Fleet Street, and as we go, notice what a number of narrow alleys or passages there are on the left. All of them are interesting, but we shall only have time for the special one we are going to see.”

“Crane Court, Bolt Court, Johnson’s Court—we’re getting near him, aren’t we?” Betty said as she read the names aloud.

“Fleet Street is full of memories of Dr. Johnson. He had many dwelling places, but however often he moved, he never went far from Fleet Street.”

Godmother now led the way up a narrow alley called Bolt Court, and in a moment they came to a little enclosure in which one or two of the houses were of the kind Betty had seen in the Temple, old, square, and built of dark red bricks, while others were quite modern business places.

“This is Gough Square, and here is Dr. Johnson’s house,” Godmother said, stopping opposite one of the old houses with the tiniest little garden in front of it. “For years it was used as an office for printers, and it would have been pulled down by now if a gentleman called Mr. Cecil Harmsworth had not bought it and given it to the nation to be kept for ever in memory of Dr. Johnson. Now we’ll ring the bell and go in, and you shall see what the inside of an eighteenth-century house was like. For this one has been arranged as nearly as possible as it was in Dr. Johnson’s time.”

Betty was delighted with the panelled rooms, with the quaint deep cupboards in the walls, one of which, as the interesting housekeeper who showed the place told her, was a powder closet, where the gentlemen’s wigs and the ladies’ hair were powdered before they went to parties or “routs,” and “assemblies,” as in eighteenth-century days, parties were called. Upstairs there was a big attic stretching the length of the house, and here it was that Dr. Johnson worked at his great and famous Dictionary. But every room was full of memories of him in the shape of letters or books arranged in glass cases, or in pictures on the walls.

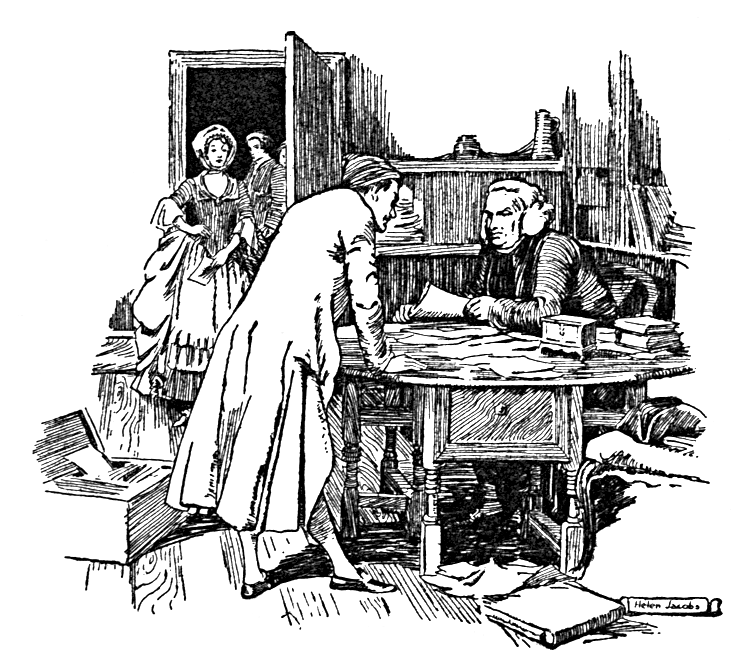

“Here is the picture I told you about, showing Dr. Johnson and his friend Goldsmith together,” said Godmother, pointing to one of them. “It’s very interesting because the scene it represents, took place over there in Wine Office Court,”—she pointed out of the window to an opposite street,—“where at one time Goldsmith lived.”

“What are they doing?” asked Betty, looking at the painting. “That’s Goldsmith in the funny night-cap, I suppose?”

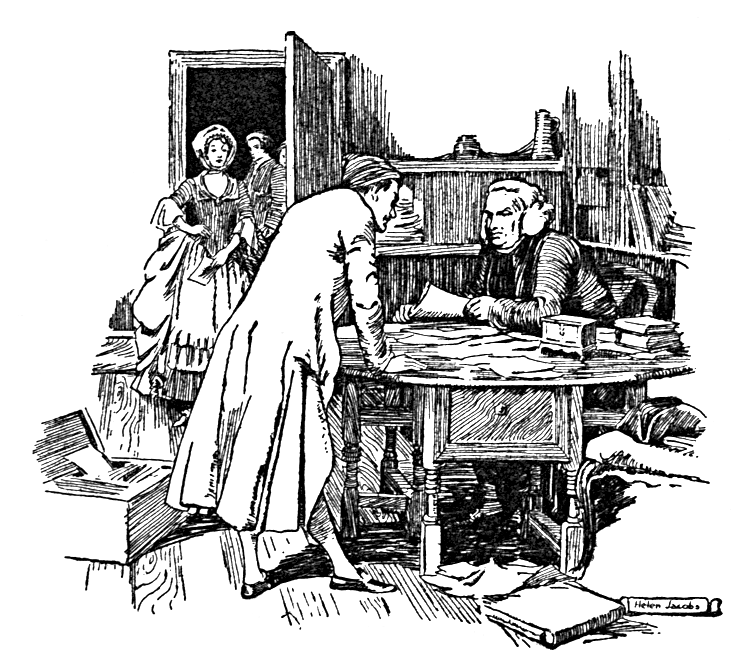

The caretaker, who seemed to know everything that was to be known about the house and its belongings, began to tell her the following story of the picture.

“Though he was the kindest-hearted man in the world, Oliver Goldsmith was so careless and happy-go-lucky that he was always in debt, and one morning before he was dressed, he sent over a messenger to this house in which you are standing, to borrow a guinea from his neighbour, Dr. Johnson. Dr. Johnson crossed this little Square which you see from the window, and went to his friend’s lodgings opposite, to find out what was the matter. The picture shows you why Goldsmith wanted the money. There is his angry landlady waiting to be paid, and there is Goldsmith in his night-cap and dressing-gown with Dr. Johnson sitting opposite to him, looking over some sheets of writing.”

“Why is he doing that?” Betty asked.

“Well, he knows that his friend is penniless, and even though he now has the money to pay his landlady, he must have some more to go on with. So he has asked him if he has written anything that might possibly be sold. Goldsmith, you see, has been rummaging in that box into which he has thrown stories he has written from time to time, and the manuscript he has just handed to Dr. Johnson is no other than The Vicar of Wakefield!

“That’s the story so far as the picture tells it. But we know what happens next. Dr. Johnson puts the manuscript into one of those big pockets of his, goes out, and in a short time returns with sixty pounds—the price he has received for the book by which Oliver Goldsmith is best known—the famous Vicar of Wakefield.”

“And perhaps if Dr. Johnson hadn’t taken it, it would never have been published at all?” Betty suggested.

“Very likely,” agreed Godmother. “Well, now that you’ve seen Dr. Johnson’s house, we’ll go and look at the inn in which he and Goldsmith often sat.”

They crossed the little Square, and found themselves almost at once in Wine Office Court.

“Unluckily Goldsmith’s house has gone, but here is the Cheshire Cheese, one of the oldest inns in London, for it was old, when Johnson and Goldsmith used to come here.”

They stepped then into the quaintest of taverns! It was dark, with low ceilings and sanded floors, and when they had looked at everything and seen the chair pointed out as Dr. Johnson’s, Betty could scarcely believe they were in modern London.

“I understand now why we don’t need ‘the magic’ to see a good deal of London as it was in the eighteenth century!” she remarked. “There’s quite a lot of it left.”

“Much more than most people know about, because only a few take the trouble to discover it hidden away behind modern buildings,” Godmother returned.

“Is there any other place left in Fleet Street that Johnson used to go to?” Betty asked. “You said he was always walking about here.”

“I’m afraid most of the other houses with memories of him have been pulled down, but before we leave Fleet Street let us go into the church where Sunday after Sunday he worshipped. You know St. Clement Danes? Here it is, standing in the middle of the road near to the Temple—one of the seventeenth-century churches built after the Fire.”

They entered, and Betty followed her Godmother up into the gallery where a tablet on a certain pew near the pulpit, marked Dr. Johnson’s seat.

“It’s interesting to know just where he sat,” Betty said, as they left the church. “Is the next place we’re going to, hidden away like Gough Square, Godmother?”

“Far from it. I’m going to take you now to the Adelphi, to which business people who have offices there, go every day.”

“The Adelphi? That’s a turning out of the Strand, isn’t it?”

“Yes. Have you ever asked what the name means?”

Betty shook her head.

“Does it sound to you like an English name?”

“Adelphi,” Betty repeated. “No, it doesn’t. What language is it?”

“Greek. It’s the Greek word for brothers.”

By this time the car had turned up a street near Charing Cross Station, and was moving slowly past lines of houses which Betty recognized as belonging to the eighteenth century.

“Look at the name of that street,” said Godmother, pointing to it.

“Durham House Street,” Betty read.

“Well now, remember the Strand as we saw it by magic about the time of Elizabeth, when stately houses surrounded by gardens, stood facing the river. Just here, where we are driving through these streets of eighteenth-century houses, stood Durham House, where Lady Jane Grey was born. We saw it, if you remember, when we were in Queen Elizabeth’s reign. That accounts for the name Durham House Street which you’ve just seen. But it doesn’t account for names like Adam Street, and James Street, does it?” As she spoke, Godmother was pointing to them as they appeared written up on the walls of corner houses. “I’ll explain about that in a minute, when you’ve looked at this beautiful place we’re coming to, called Adelphi Terrace.”

They had turned into a broad road, open on one side to the river, and lined on the other side by a row of stately houses with delicately ornamented flat pillars, against the walls.

“The Adelphi, as you see,” she went on, “is really a whole district laid out in streets of eighteenth-century houses, built over the ground where Durham House once stood. About a hundred and fifty years ago, when Dr. Johnson and Goldsmith were living, there was a Scotch family of four brothers in London. Their names were John, James, Robert and William Adam. They were all architects, and also designers of a beautiful kind of furniture which has ever since been called Adam furniture, and is now very valuable. These brothers built this little part of London which was not only called the Adelphi—that is ‘the Brothers’—in honour of them, but each brother gave his Christian name to a street, while yet another street bears the surname of the family. So we have Adam, James, John and Robert Streets. There used to be a William’s Street, but that has been changed to Durham House Street within the last few years.”

“Poor William!” said Betty. “He’s gone out of the family! Still, the new name does remind us of Durham House and Lady Jane Grey, doesn’t it? Oh! two of the brothers, Robert and James, lived here, Godmother!” she went on, pointing to a tablet on one of the houses in the terrace. “And here’s another tablet next door. It says that David Garrick lived in this house. Who was David Garrick?”

“A famous actor of the eighteenth century and one of Dr. Johnson’s friends. He acted at Drury Lane Theatre where, eighty years or so before his time, Pepys, you remember, used to go to see the pretty actress, Nell Gwynne. But you will read about these eighteenth-century people when you are older, and perhaps feel as I do, that you know them all very well. Take a last look at this Adelphi, because it’s a good example of the sort of architecture that belongs to the time of George the Second and Third. There are many other eighteenth-century streets and nooks and corners scattered about London among the forest of new buildings that has sprung up since the reign of George the Second. But I shall leave you to find them for yourself. It will make a nice occupation for you when you go for a walk! Now we must rush home if we want any lunch to-day.”

“But you won’t forget the ‘magic,’ will you?” urged Betty anxiously.

_______________________________

In the white parlour, an hour or two later, she sat full of expectation, watching Godmother as she took a volume from the enchanted cabinet.

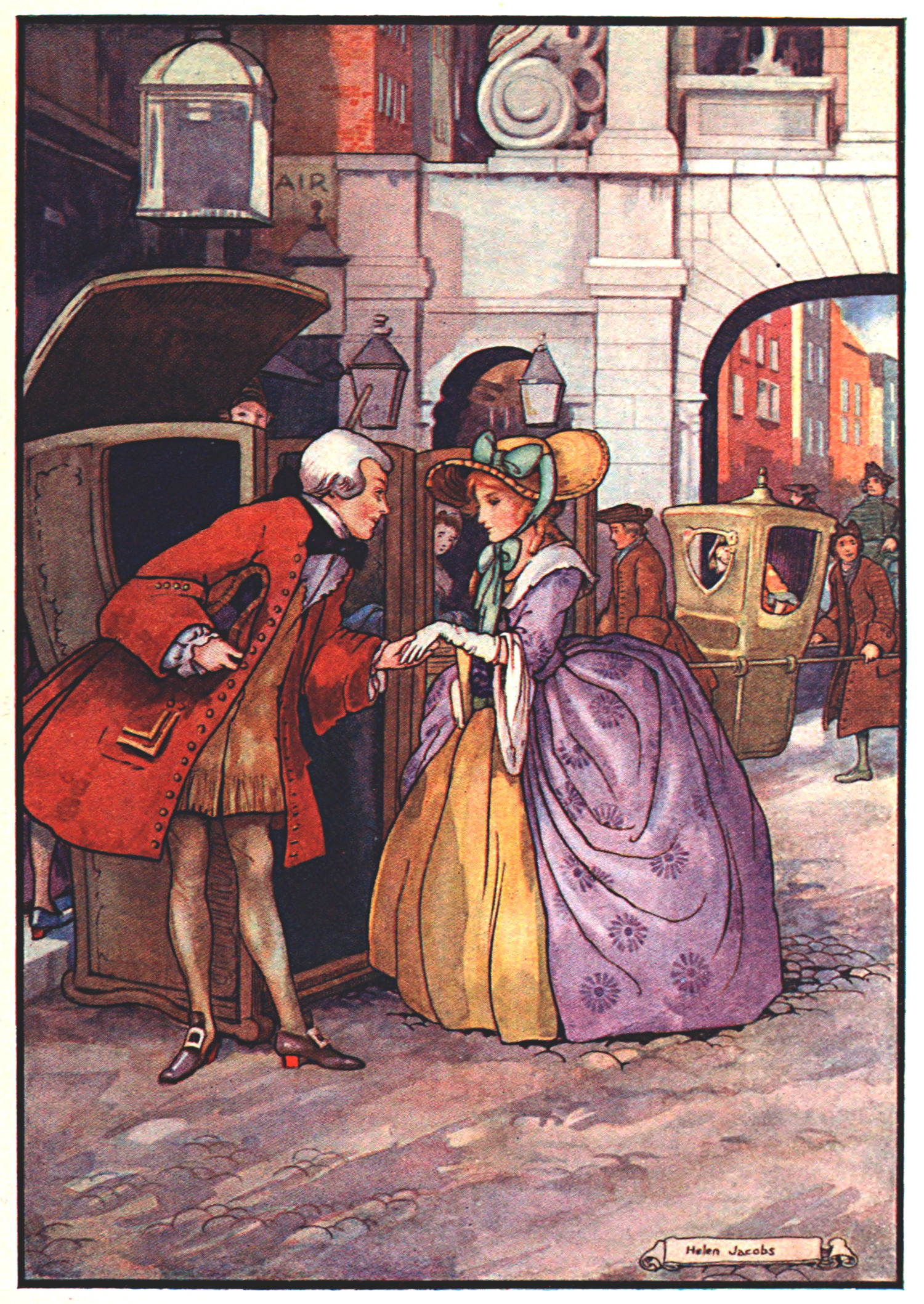

A SEDAN CHAIR

“Here is the book that will take us back to-day,” she said. “It’s called Boswell’s Life of Johnson, and it’s almost as good for news of the eighteenth century, as Pepys’ Diary is, for news of the seventeenth. Shut your eyes, hold the book in the magic way, and say, as Johnson used to say to his friend Boswell, ‘Sir, let us walk down Fleet Street.’”

_______________________________

In a flash they were there, and at first sight Betty could scarcely believe it was the same Fleet Street she had left only a few hours previously. In a minute or two, however, she recognized it, in spite of the changes, for she stood close to the entrance to the Temple, and not far from it rose the church of St. Clement Danes. But the great pile of the new Law Courts had vanished, and so had the monument with the Griffin upon it in the middle of the road. Where that had stood an hour or two previously there stretched a fine stone gateway, and a line of little shops took the place of the Law Courts.

“That’s Temple Bar,” said Godmother, pointing to the gate. “If you had lived forty y