CHAPTER VII.

MOMIEN.

Momien—The town of Teng-yue-chow—Aspect and condition—An official reception—Return visit—Government house—A Chinese tragedy—The market—Jade manufacture—Minerals—Mines of Yunnan—Stone celts—Cattle—Climate—Environs—The waterfall—Pagoda hill—Shuayduay—Rock temples—Ruined suburbs—City temples—Four-armed deities—Boys’ school—A grand feast—The loving-cup—The tsawbwa-gadaw of Muangtee—Keenzas—The Chinese poor.

A retrospect of the journey thus far showed that since our departure from the Burmese plain we had been steadily ascending. Although the altitudes could not be taken with accuracy, owing to the inefficiency of the instruments which had been supplied at Rangoon, such observations as it was in our power to make were made; they were subsequently reduced by the surveyor’s department at Calcutta, and the results are approximately correct. Where it was necessary to depend on speculation, care was taken to under-estimate the apparent altitudes. The natives always speak of ascending to Momien and descending from it, and, applied to the western approaches, this expression is fully justified. From Bhamô, four hundred and fifty feet above the sea-level, we had climbed over the Kakhyen hills to the Sanda valley, which, at Manwyne, lies at least two thousand feet above Bhamô. Throughout the forty-eight miles of its length, this valley rises so gradually as to present the appearance of a long level avenue, divided into three stages, till the head of the Muangla division is reached. From this it is requisite to ascend by a detour over the Mawphoo height, to attain the fourth stage, or the valley of Nantin, lying one thousand feet above Manwyne. From the upper extremity of the Nantin valley, the long steps, so to speak, of the Hawshuenshan glen rise fourteen hundred feet to Momien. Thus, the latter city, one hundred and thirty-five miles from Bhamô, occupies a site on a plateau elevated more than five thousand feet above the level of the sea, which is declared by native reports to be the highest inhabited position in the mountainous region of Western Yunnan.

The Chinese city of Teng-yue-chow, better known by its Shan name of Momien, is said to have been built four hundred years ago by a governor of Yung-chang, obeying the king of Mansi or Yunnan, which the Shans call Muangsee. It was probably built as a frontier garrison, to hold in check the recently conquered territories of the Shan kingdom of Pong. It thus became, as it still is, the ruling head-quarters of the tributary Koshanpyi or Nine Shan States, now represented by those of the Sanda and Hotha valleys, with Muangtee, Muang-mo, and Muangmah. We were able to procure a Chinese history of Momien as well as of Tali, though both had become rare, as the rebels had destroyed the woodblocks. These copies were brought by Major Sladen to England, in order to be deposited in the British Museum. It is to be hoped that some one of our Chinese scholars will find leisure to translate these works, which would probably throw valuable light on the little known history of these regions.

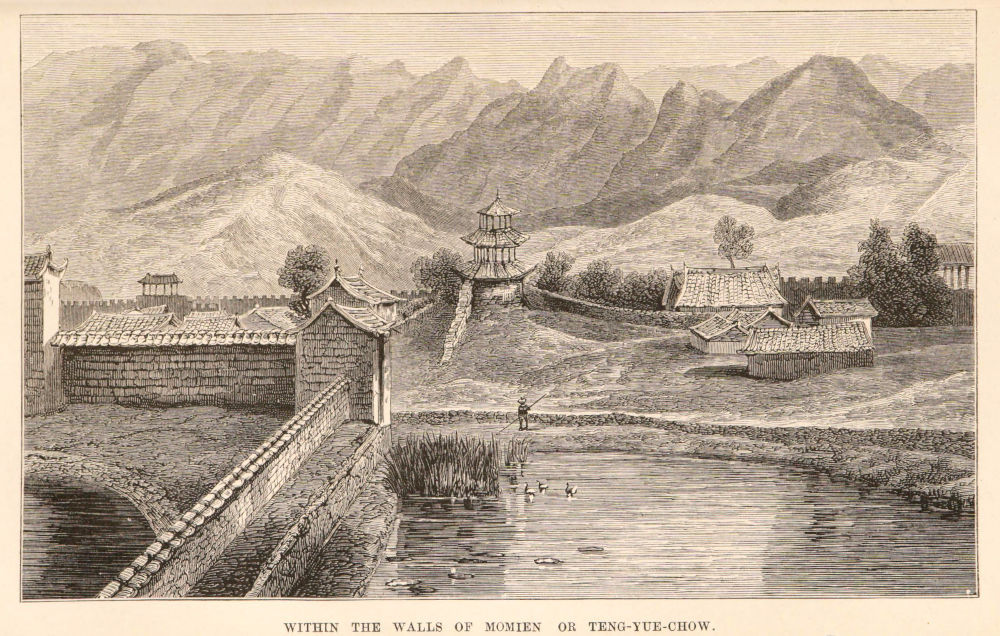

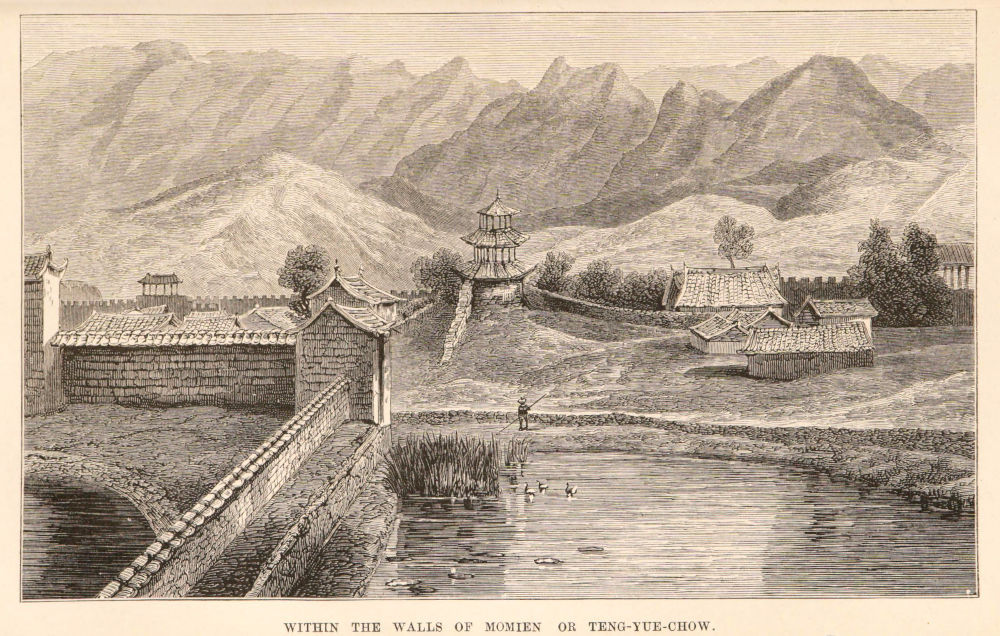

The plan and construction of the city show that it was built as a fortress. It occupies an area of five furlongs square, enclosed by a strongly built stone wall, battlemented or crenellated, twenty-five feet high. Twenty yards from the walls a deep moat surrounded the once city; it was still perfect on the eastern and southern faces, but had degenerated into a broad puddle, the favourite wallow for the bazaar pigs, on the western. The masonry is admirable, the well hewn slabs of lavaceous rock, two to four feet long, being laid in mortar, hardened almost to the consistency of the stone, while the moat is faced with stones laid together without mortar, so close and true that a penknife can scarcely be inserted between them. Inside the wall, an earthen rampart, about thirty feet wide and eighteen feet high, serves as a battery, or parade ground, as well as a promenade. There are no bastions, but at intervals turrets rise from the rampart, built of blue burned bricks, the smooth surface and sharp edges of which are uninjured by the wear and tear of centuries. The four gateways, to each of which corresponds a substantial bridge spanning the moat, are lofty and well built; but at the time of our visit, two of these gates had been built up. The south-western or bazaar gate was especially fortified by a semicircular traverse, an entrance in the side of which led into a tunnel-like archway, over which rose a lofty watch-tower, with concave roof, supported by strong pillars. The inner doorway was closed by heavy ironclad wooden valves, which were carefully shut at nightfall. Viewed from a distance, the walls and turrets, with a lofty pagoda and the roof of the watch-tower, seemed to indicate a populous and thriving town; but within the walls was almost emptiness. The broad rectangular streets were comparatively deserted, save by a few Panthay soldiers, who with their families formed the sole intramural population. But few houses remained uninjured, the best of these being the dwellings of the governor and his officers. The numerous temples had been gutted and half demolished. The images and huge stone incense vases had been overthrown and broken, while the ruined walls pitted with bullets showed the fierceness of the struggle which had taken place. The absence of all the wonted bustle and noise of a crowded city was made more striking by the evidence on all sides of the former prosperity and population.

Our stay at Momien extended over six weeks; but the state of the country, combined with the weather, reduced us almost to inaction. The depressing monotony of life under these circumstances was, however, relieved by the unvarying kindness of the hospitable Panthays. Our first day was devoted to arrangement of ourselves and baggage, in which a crowd of curious visitors assisted by uttering astonished “Iyaws!” at everything possessed by the foreigners, whose persons and goods each was anxious to inspect.

WITHIN THE WALLS OF MOMIEN OR TENG-YUE-CHOW.

The following day having been appointed by the governor for our reception, we entered the town in state, preceded by twenty Mahommedan sepoys of the escort, carrying the presents. These consisted of green and yellow broadcloths, muslins, gaudy rugs and table covers, double-barrelled guns and revolvers, with all appliances, powder and shot, penknives, scissors, a binocular glass, telescope, and musical-box, and a quantity of Bryant and May’s matches.

A large but well-behaved crowd of poverty-stricken Chinese had assembled, who matched well with the ruinous houses of the suburb. We entered by the south-western gate into a narrow dirty street, from which a lane led to the governor’s house, surrounded by a low wall. The gateway, about fifteen feet high, was formed of plain squared stone pillars, with others laid horizontally across them, like the cross beams of a doorway. This led into the usual Chinese succession of quadrangular courts. In a small circular pavilion were stationed some ragged musicians, who struck up a lively air on gongs and cymbals. As we crossed the court to the house, a salute was fired from three small cannon that were stuck into the ground, with muzzles upwards. A rabble followed into the doorway leading to the inner court, at the end of which, in the reception hall, sat the governor. He rose to receive us, and motioned us to sit on his left hand, at a long table, on which the presents were laid before him. Behind his seat there was a raised recess, covered with red cloth, in which stood a small chair of state. The sides of the room were hung with long narrow strips of blue and red cloth, covered with Chinese characters in gold-leaf. The superior officers occupied chairs along each side of the room, and a crowd of underlings blocked up the entrance. The governor was a powerful man, fully six feet three inches high, with prominent cheek-bones, heavy protuberant lips, slightly hooked nose, and faintly oblique eyes. His face was bronzed by exposure, and a deep indentation between the eyes, with other scars, told of campaigns, in which he was said to be ever foremost in the fight. He wore a grey felt hat, resembling a helmet placed sideways, the front half of the rim being turned up, and the back part downwards. A gold rosette, set with large precious stones, formed a handsome ornament in front, and a long blue silk topknot hung down behind. A pale blue silk coat, richly figured, exactly resembling a dressing-gown, completed his costume. Sladen expressed our deep regret at the death of the two officers, and promised to suggest to our government to compensate their families. The governor replied that we were not to distress ourselves, as they considered it an honour to die as those men had done. As to the opening of trade, he declared that any number of English merchants might visit Momien in the ensuing November; that he had arranged with the Shan tsawbwas, and could manage the Kakhyens, so that caravans should pass safely; but he hinted that there were too many people then present to admit of this question being discussed. He expressed great pleasure at the presents, and the musical-box being set agoing excited universal admiration; the matches astonished the company; but the sincerest satisfaction was called forth by the guns and powder. Tea, preserved oranges, jujubes, and sugar-candy were served round. In the course of general conversation the governor stated that the Sultan had been pleased to hear of our intended visit to Momien; but he feared that the road to Tali-fu was too infested with Chinese bands to allow of our proceeding further.

The governor, attended by an armed retinue, paid his return visit of ceremony the next day, carried in a gorgeous chair, and dressed in full mandarin robes, while his officers were gaily attired in white cotton jackets, braided, and adorned with silver buttons. They made a gallant show of gold swords, silver spears, banners, and other insignia. Presents were brought in, consisting of a bullock, sheep, trays of confectionery, and forty thousand cash. The latter were at first declined, but the courteous Tah-sa-kon would take no refusal, and the cash furnished an acceptable largess to the escort and followers, giving each about one rupee. The mission funds were, in truth, rather low about this time, which, it may be noted, operated against the acquisition of specimens of the local manufactures, save to a very limited amount. Among the confectionery sent was a quantity of fine white granulated honey, and a strong warning was given against the use of onions, as the combination of onions and honey in the system would be a certain poison.

When taking leave, the governor suggested that now the claims of etiquette had been satisfied, we should consider ourselves free of government house, as well as the town in general, and come and go as we liked, and promised that he would visit us sans cérémonie. Our guard and the Panthays fraternised completely, their common faith uniting them, and the Chinese Mahommedans treated the true believers from India with great respect. The jemadar was indeed in constant request to officiate at the mosque, till he lost his voice by over-exertion.

True to his promise, the governor appeared bent on carrying us off to an entertainment at his house. We were received in the same room as before, but were invited to sit with our host on the dais at the further end; constant relays of tea-cakes and sweetmeats were brought in, to all of which each man was expected to do his duty. Shouts of laughter reached our ears from time to time, as the ladies, our host’s four wives and their maids, amused themselves in the adjacent zenana with the magnetic battery. Our circle was presently joined by the tsawbwa-gadaw of Muangtee, who was on a visit to the governor. She was attended by several well-dressed Shan ladies, and they chatted and laughed with that charming good humour which seems characteristic of the Shans.

We were then shown over the private apartments by the governor himself, who led us first to his bedroom, a snug little windowless room, lighted by two doors facing each other, containing a large four-post bed, with blue silk curtains looped up by silver chains, and a comfortable couch, while the walls were decorated with an English eight-day clock, and Chinese pictures and old armour. Passing through the room, we entered a small court, where a number of tailors sat busily at work in a verandah. This led to the zenana, or women’s apartments, a pretty range of buildings, surrounding a small garden, ornamented with large vases, containing dwarfed fruit and pine trees, and stone tanks filled with goldfish. The trees included peach, plum, orange, box, &c., about two to four feet in height, which had been dwarfed by tying knots in the stem of the sapling. On our way back, we passed through a room hung round with war hats gorgeously decorated with the tail feathers of the Lady Amherst and golden pheasants, and with the handsome fox-like brush of the wah (Ailurus fulgens, F. Cuv.). After this inspection, we were conducted to an open hall, in which a theatrical entertainment was to take place. More tea and cakes were produced, while large copper vases of incense burned close to us, and the heavy fumes produced a drowsy feeling. The stage was a pavilion about twenty feet long, closed on three sides, with two doors behind it, one for the entrance and the other for the exit of the players. The orchestra of violins, gongs, and cymbals, occupied the back of the stage, and discoursed most monotonous music, like the clatter of crockery, with occasional bangs and screeches. A small panelled picture of birds and flowers served as scenery, and the properties were a table like an inverted pyramid, with a chair on either side of it. The characters were all sustained by male performers, who, on this occasion, presented a tragedy, turning on the Chinese virtue of filial obedience. This required the hero to obey his mother by rebelling against his father-in-law and killing the princess, his wife; but the latter solved the difficulty by suicide, and mother and son joined in lamentation over her. The hero had his face painted red, and adorned with a long black beard and moustache; he was accoutred in a gorgeous coat, richly embroidered with dragons and flowers, a hat with a fine bushy tail of Ailurus fulgens, red trousers, and black satin boots. He bellowed and blustered, and strode about the stage as if practising the goose-step; the close of every speech being emphasized by a bound in the air. While the play was going on, we were expected to consume the contents of eight bowls containing fowl chopped up with salted goose, dried prawns, mushrooms, vegetables, &c., each dish being evidently a choice specimen of Chinese cuisine. Ahyek, or samshoo, was then served round, but the governor, as a good Mussulman, abstained from the forbidden liquor; small saucers of rice and condiments came next, but after three hours of eating we beat a retreat from the still interminable feast and drama.

The hospitable governor renewed his invitation the next afternoon, when a farcical comedy was played, which was very broad, but fortunately brief. As this was the market-day, two officers were detached to escort us through the bazaar, the principal street of which extended half a mile straight from the south-western city gates. Each side was occupied by permanent shops, and a double row of stalls, protected by huge umbrellas, lined the whole length of the street. A dense crowd of Chinese, Shans, and Panthays, with a small sprinkling of Leesaws and Kakhyens, thronged every avenue; the people were quite good-humoured, but their curiosity would have been very troublesome but for the presence of the officers. This, however, was only at first; during our stay we roamed at will through the streets of the bazaar suburb, as well as within the walls. The shops were small, one-storied cottages, each devoted to a particular trade. Drapers, booksellers, druggists, dealers in tobacco and nuts, provision merchants, displayed their several wares, but, except on the market-day, with little custom. Numerous eating-houses were crowded by the better class of customers, while the poorer villagers were supplied by lads hawking comestibles. The stalls made a rich display of vegetables and fruit; among the former were peas, green and dried beans, potatoes, celery, carrots, onions, garlic, yams, bamboo shoots, cabbage and spinach, and ginger; the fruit comprised apples like golden pippins, pears, peaches, walnuts, chestnuts, brambleberries, rose-hips, and three sorts of unknown fruit. Mushrooms were in great demand, as well as a dried, almost black lichen; black pepper, betel-nut, and poppy capsules were seen on almost every stall, and salt sold in compressed balls, marked with a government stamp. Other departments contained coloured Chinese cloths and yarns, and buttons, English long and broad cloth, needles, and brass buttons, Mahommedan skull-caps, embroidered in gold thread, rings, mouth-pieces and brooches of amber and jade, opium pipes, and Chinese hookahs. Running at right angles to the principal street is another devoted to tailors and ready-made clothes stores, and coppersmiths, who supply all kitchen appliances, and manufacture the copper discs used in cutting jade. Along this street we came to the store of the principal Chinese merchant, who invited us in, and was very hospitable. His laments over the decay of the former trade with Burma, caused by the civil war, showed clearly to which side his sympathies inclined; and it was evident that he, as well as all the non-Mahommedan Chinese, were only kept to their present allegiance by the strong hand. The whole bazaar suburb was surrounded by a low brick wall with several gates, each guarded by a sentinel at night, and the Chinese resided here, being evidently excluded from the city. Although the manufactures seemed to be in a very depressed state, the quarters of the various artificers were still traceable; in a by-street we had an opportunity of viewing the manufacture of jade ornaments. The copper discs employed, a foot and a half in diameter, are very thin and bend easily; the centre is beaten out into a cup, which receives the end of the revolving cylinder. We watched two men at work, one using the cutter, and the other a borer tipped with a composition of quartz and little particles resembling ruby dust. Both were driven by treadles; the stone is held below the disc, under which is a basin of water and fine, silicious mud, into which the stone is occasionally dipped, the operator taking handfuls of the mud. The stones are cut into discs one-eighth of an inch thick, when intended for ear-rings, and handed over to the borer to be perforated. The most valuable jade is of an intensely bright green, something like emerald; but red and pale pink qualities are highly prized. In the extensive ruins outside the bazaar there was ample evidence, in the rejected fragments of jade, that the manufacture must have been formerly carried on on a much more extensive scale. The jade is obtained from the mines in the Mogoung district, where large masses in the form of rounded boulders are dug out of the pits; in former times a large quantity was yearly imported to Momien. One hundred rupees was the price asked for a pair of bracelets of the finest jade, and at Bhamô four rupees purchased rings worth £2 at Canton.

Of amber-workers, who manufactured rosaries, rings, mouth-pieces, &c., from the amber brought from the mines in the Hukong valley, near Mogoung, but few remained at the time of our visit. The amber most prized is perfectly clear, and the colour of very dark sherry. A triangular specimen, one inch long, and one across, cost ten shillings.

At the bazaar there was a plentiful display of the mineral wealth of Western Yunnan, which is rich in gold, silver, lead, iron, copper, tin, mercury, arsenic, and gypsum; and we obtained small specimens of most of these minerals, including a yellow orpiment, exported in quantities from Tali to Mandalay, whither a large amount of tin also is annually sent. The copper is brought from a range of hills near Khyto, three days’ march to the north-east. It is smelted on the spot, and brought in flattish pigs. The same hills are said to yield all the iron and salt used in Western Yunnan; but the most precious product of the Khyto mines is galena. Of this, a small specimen has been assayed by Dr. Oldham, who has pronounced it to be among the richest that he has ever seen; it yields 0·278 per cent., or 104 oz. of silver to the ton of lead. Flints and large quantities of lime are brought from Tali-fu, where large quarries of fine white marble exist. Sulphur is procured in the neighbourhood, but we could not learn the locality. Li-sieh-tai was subsequently reported to be raising sulphur to the south-west, and an Old Resident[26] in Western China mentions a rich mine of sulphur belonging to the northern frontier town of Atenze, behind a little mine of saltpetre. The Chinese report on the mines of Yunnan, appended to the records of the French expedition, states that in 1850 the copper mines of Yunnan, of which Tali-fu is the principal depot, produced over eleven thousand tons, and the silver amounted to two millions of francs. The Old Resident, however, says that before the outbreak of the rebellion there were one hundred and thirty-two copper mines, government knowing only of thirty-seven; and as the above account was calculated on the returns made to the government, who exact from thirty to fifty per cent. of the produce, it is plain that the mineral wealth of Yunnan is even greater than it is set forth in that report. Gold is brought to Momien from Yonephin and Sherg-wan villages, fifteen days’ march to the north-east; but no information could be obtained as to the quantity found. It is also brought in leaf, which is sent to Burma, where it is in extensive demand.

In the drug-shops a powder was vended as a nervous restorative, made of the horn of an antelope ground down, and sold at one rupee per tickal;[27] and the pharmacopœia also included the powdered shells of a tortoise (Testudo platynotus, Blyth), imported from Upper Burma, and snuff made of sambur horn, used as a styptic for bleeding from the nose. We were much surprised to find stone celts openly offered for sale. When it was known that we would purchase, numbers were brought in, and we acquired a collection of one hundred and fifty specimens, at prices varying from two shillings to sixpence. Their poverty and not their will constrained the owners to part with them, for they are believed to confer good luck on the owner, and to possess curative properties if dipped in medicine, and are exhibited to procure easy parturition. They are usually turned up by the plough; and the popular belief is that they fall from the sky as thunderbolts, and take nine years to work up to the surface. The high estimation in which they are held suggests that a Chinese Flint Jack made a profitable business of imitating the real implements, or manufacturing amulets of the same type. A large number of those purchased are small, beautifully cut forms, with few or no signs of use, and made of some variety of jade; but there is no reason to doubt the authenticity of the larger forms which were brought to us. Bronze celts are also found, but are valued at their weight in gold; we managed, however, to purchase one at Manwyne on the return journey. It belongs to the socketed type of celts without wings. The composition of the bronze is the same as that of the celts found in Northern Europe—tin 10, copper 90.

In consequence of a long period of drought preceding our arrival, the slaughter of animals had been forbidden, as it was feared that the rain would be withheld as a punishment, a curious instance of Buddhist superstition affecting the Panthays and Chinese; but in two days the rains set in, and the prohibition was removed. The markets were thenceforward well supplied with bullocks, buffaloes, sheep, goats, and pigs. The buffaloes are chiefly used for agriculture; the beeves have no hump, and are small but well made, generally of reddish-brown colour, deepening to black. The numerous sheep belong to a large blackfaced breed, with convex profiles. Two kinds of goats are common; one with long shaggy white hair nearly sweeping the ground, and flattened spiral horns, directed backwards and outwards; the other kind has very short dark brown hair, short shoulder list, and full beard, with similar flattened spiral horns, but not so procumbent. The pigs seemed to be all black. Remarkably fine ponies were common; but the mules, which were much more numerous, are more prized. Fowls, ducks, and geese are abundant and large; and last, though not least, cats, all of a uniform grey, with faint darkish spots, made themselves at home everywhere. But we noticed very few dogs, those seen being black with shaggy coats, resembling the shepherd dogs of the south of Scotland.

It has been mentioned that the rains set in soon after our arrival. From June 1st the south-west monsoon prevailed, with very few fair intervals. The sky was obscured by thick, misty clouds, that wrapped the hills in dense folds. As a rule, the rain fell very heavily; but there were days together when it was little more than a thick Scotch mist in a dead calm. Occasional thunderstorms of terrific grandeur burst over the valley, accompanied by strong gusts from the south-west; but the most characteristic feature of the weather was the generally perfect stillness of the atmosphere, while low leaden clouds poured down incessant rain, generally heavy, but sometimes only a gentle drizzle, all which combined had a sufficiently depressing effect on us. The temperature was by no means oppressive, the mean maximum in June being seventy-four degrees, and the minimum sixty-two degrees. The natives strongly assert that the climate is unhealthy for strangers, and we all suffered more or less from intractable diarrhœa. Smallpox, too, was prevalent; and one of our collectors and a Kakhyen sub-chief, who had accompanied us, died from it. We were strongly cautioned against the use of the river water, to which the natives attribute the prevalence of goitre, which is most unpleasantly remarkable among men and women and children, some goitres being so large as to require special support; even young infants were observed affected by it, and in their case it must have been congenital. Otherwise the children seemed very healthy, notwithstanding their rags and dirt, and not a single case of fever was observed, though about sixty or seventy patients were treated for other diseases.

The fact that by far the greater part of the valley is under water for six or seven months, during three of which it is little better than a huge morass, would not seem to recommend it as salubrious; but it must be remembered that it lies more than five thousand feet above the level of the sea, in the twenty-fourth parallel of north latitude, and is a comparatively dry and temperate country, singularly destitute of trees, which conditions would combine to place it beyond the range of miasma.

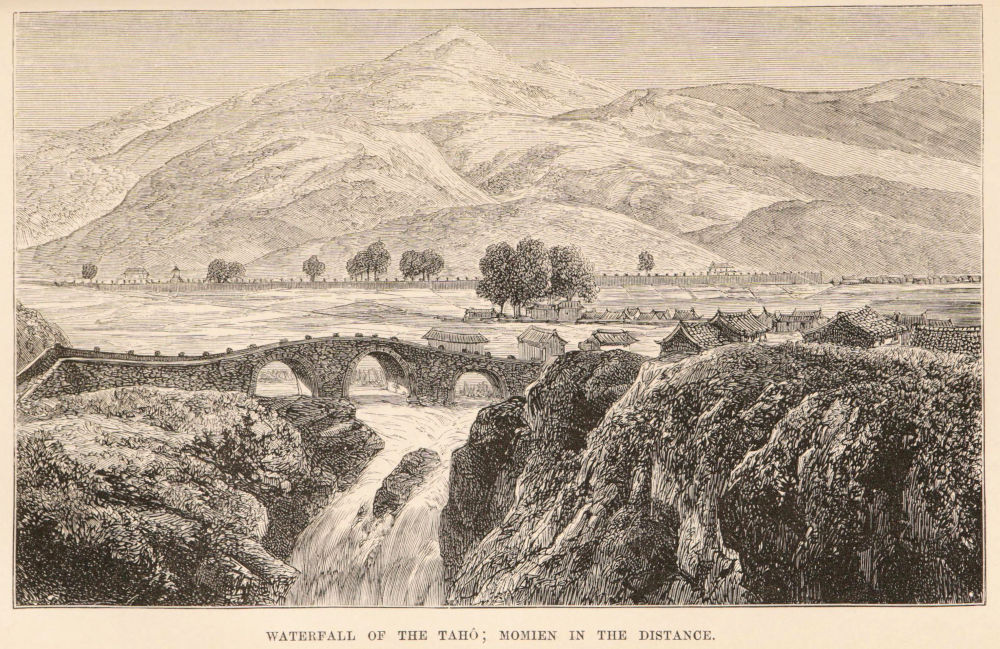

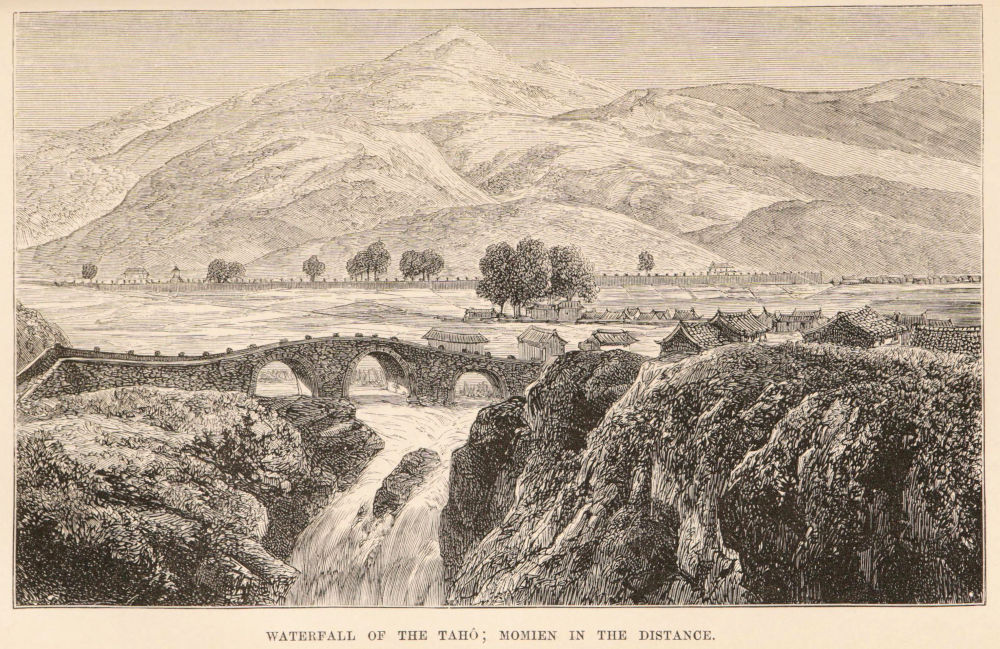

The worthy governor showed great anxiety about our health. He refused, on the score of security against prowling robbers, to let us shift our quarters, but sent guards to accompany us in an occasional ramble round the precincts of the city. So great was the insecurity that we dared not venture more than a few hundred yards from the walls unattended. A favourite walk was to a place less than a mile to the north-west of the town. Here the Tahô, after flowing through the valley, precipitates itself, in an all but unbroken sheet of water, over a cliff one hundred feet high; thence it foams down a steep glen to the little valley of Hawshuenshan. Immediately above the fall the stream is spanned by a substantial stone bridge of three arches with roofed approaches. Below this the thick bed of basaltic trap, over which the river leaps, is worn into a miniature horseshoe; and the overhanging luxuriant vegetation of ferns and brambles, and wild roses with double flowers, formed a strikingly beautiful scene. In the rains the body of water was so great that a column of spray ascended which was visible two miles off. From this point the crenellated walls of Momien, with the distant background of lofty ranges, completed a striking picture. Above the bridge the Tahô flows down in a tortuous stream twenty yards broad, well stocked with large gold carp (Cavassius auratus, Lin.), between banks ten feet high; and the rice fields on either side are irrigated by large wheels raising the water in long bamboo buckets, which discharge themselves into wooden pipes leading to the fields. These wheels are numerous in the valley.

WATERFALL OF THE TAHÔ; MOMIEN IN THE DISTANCE.

After visiting the waterfall, we ascended the pagoda hill, about one thousand feet above the town. The path led through potato-fields now in full bloom, the plants grown in ridges, and earthed up with a home-like effect. The leaf is smaller than that of the home plant, and the tubers in the market had a thin red skin; but they were very good, and in great demand at fourpence for three pounds and a half. Nothing could be learned of the introduction of this plant, nor of the celery, which is also largely cultivated, and seemed quite as out of place. The potato, however, is called yan-gee, evidently the same as yang-yu, foreign root, which, according to Mr. Cooper,[28] is its name in Sz-chuen, where it is said to have been introduced by the foreign teachers, i.e. the French missionaries, long ago. The lower slope of the hill was covered with stone tumulus-shaped tombs, the arched head of each containing a tablet with an epitaph. Ruder graves were simple earthen tumuli, each with its arched opening blocked by a large stone. The slopes of the hills surrounding the valley are dotted with similar graveyards—mute records of the population that once thronged the ruined villages lying below. Near the summit stood a pagoda, a whitewashed round brick tower on a stone base with six projecting rings. The hill itself, like all the eminences around, was covered with fine grass, and a number of mules were grazing under the protection of a Panthay guard. A pleasant illustration of the prevailing insecurity was given a few days later, when this guard was attacked and forty mules driven off by imperialist Chinese. We were unmolested, and climbed to the summit, flushing from the bracken beds a magnificent cock pheasant (Phasianus sladeni, And.), with long tail feathers, resembling some noticed in a Panthay head-dress. Sladen afterwards bagged the hen; and we also obtained a young fox with a golden-yellow coat and white-tipped brush, apparently of the Himalayan race. Returning, we observed a large arched cavern, which proved to be an old quarry of trachytic rock, which had probably furnished the city walls. On one occasion we were permitted to make a longer excursion to the valley of Hawshuenshan. Our party must have consisted of thirty-five men, all armed, the Panthay guard, equipped with spears and muskets, being commanded by the governor’s nephew, with several other officers: all this being necessary for safety during a mere suburban stroll. Turning southerly from Momien, we soon came in sight of the town of Yay-law, the deserted ruins of which stretched for more than a mile along the foot of the Deebay range. We skirted the pagoda hill, remarking a curious isolated heap of lava; no other rock was visible for miles around, and it had all the appearance of a small volcanic vent, and the rock was identical with that of the extinct volcano.

Rounding the hills two miles from Momien, a slight westerly descent led to a short narrow gorge, at the south-eastern angle of the little circular valley of Hawshuenshan. The once wealthy village of Shuayduay occupies an abrupt slope at the head of the gorge, rising in a series of terraces faced with mortarless walls of very porous lava, laid as closely as the facing of the Momien ditch, and protected by parapets of sun-dried brick. A small stream runs down the ravine, which is not more than a quarter of a mile long and fifty yards broad, to a substantial tank crossed by a broad stone platform, arched on one side to allow the overflow to escape. Facing Hawshuenshan valley, the platform expands into a handsome, crescent-shaped terrace, enclosed by an elegant stone balustrade, which forms the entrance to a temple built on the southern slope, opposite to Shuayduay. This temple, rising in terraces on the steep hillside, standing out beautifully against the background of green hills, was the only one spared by the Mahommedans, whose stern bigotry could not resist its beauty. The approach to the temple buildings lay through two curved courtyards with handsome arched gateways. The first enclosure was an open square with three sides built on the same level, the nearest one of which contained the priests’ apartments; to the right and left lay a neat garden of dwarfed fruit trees, the centre of which was occupied by a few stunted trees covered with a profusion of yellow orchids in full flower, and a magnificent hydrangea in a colossal vase; the furthest side next the hill was raised on a stone terrace four feet above the level of the rest. On this higher platform stood life-sized gilded figures of deities, with incense always burning in small black stone vases, and on a table in front of the images lay a large drum and grotesque hollow wooden fishes, which the priests and worshippers beat with short sticks. A passage led through each side of the court to stone staircases proceeding to the terrace above, and converging in its centre in an hexagonal tower, supported on stone pillars seven feet high; these formed an archway from which ascended a short flight of steps, dividing to the right and left to reach the highest terrace, nearly on a level with which was a chapel forming the upper chamber of the hexagonal tower. The upper temple occupied the whole of its terrace, built entirely of wood, except the back and end walls. The front was panelled with richly gilt lattice work, while the eaves and ceilings were coloured in imitation of porcelain. Behind a screen, adorned with richly coloured carvings of birds and flowers, sat three life-sized gilded figures on altars, apparently of porcelain. The central figure, of marble, represented a woman seated on a lotus, with a flower of the lily beneath her feet; she held forth a naked male child, seated on one hand, and supported by the other in front, the child’s sex being strongly marked. This was the goddess Kwan-yin, goddess of mercy and conception, and her presence would seem to mark the shrine as a Taouist temple. These terraced rock temples resembled those described by Mr. Cooper as visited by him at Chung Ching. The stone walls of the shrine were not carried to the roof, but finished with wooden panelling, pierced with circular windows of elegant tracery. These were so arranged that the light fell full on the seated figures. From the centre of this terrace a narrow stair led down to the chapel on the top of the hexagonal tower, within which sat a fine Buddhistic figure, with the head in white marble tinted brown.

Following a well-paved track along the hill to the east of the valley, a ride of a quarter of a mile brought us to the walled Chinese town of Hawshuenshan, built on the slope of the hill. The valley is abruptly closed in on three sides by rounded grassy hills rising suddenly round the dead level of the centre, then inundated for the rice crop. The south-west side is closed by the long low range of the extinct volcano, with a white pagoda standing out in strong relief from its black and barren side.

Hawshuenshan had evidently been a place of great importance, being a much larger town than Shuayduay, and must have contained at least three thousand inhabitants. At this time a considerable number of refugees had here found an asylum, who had fled from the deserted villages of Shangnan, Tahinshan, &c. We were shown an open grassy plot on the southern outskirts of the town which had, only a few months previously, been strewn with the corpses of imperialist Chinese. The people of Hawshuenshan had declared against the Panthays, and joined the Chinese partisan Low-quang-fang; on this plot they had been attacked and defeated. As usual, no quarter was given, and all who failed to fly were massacred, and afterwards buried where they fell. A fine temple overlooked a small stream running down from Shuayduay, and which now formed a small lake just outside the town. This water was crossed by a handsome stone bridge, with picturesque archways. From this we followed a raised causeway to the head of the valley, and, passing the Tahô waterfall on the left, ascended gradually four hundred feet to Momien. This vale of Hawshuenshan, though not more than two miles long by one broad, had been once encircled by large villages, the ruins of which still attested that before the war they must have been places of no little wealth.

With the exception of the walled bazaar, the once populous faubourgs of Momien had been laid in ruins; the heaps of bricks, the stone sides of the ancient wells deeply grooved by rope marks, and the long rows of detached mounds, with little grass-grown squares, defined the position of the southern and north-eastern suburbs. The houses of the north occupying a smaller area, surrounded by fine gardens, and shut in between the river and the city wall, seemed to have escaped demolition.

Amidst the general desolation within the city walls, two remarkable objects of art and nature stood, as it were, memorials of the past. One was a tall whitewashed pagoda seven stories in height, of the usual and familiar Chinese form. The other was a magnificent fir tree, which towered fully one hundred feet, although its top had been broken by a storm; at the height of four feet from the ground, the trunk measured fifteen feet in circumference.

In default of other resources, we spent a good deal of time strolling among the ruined temples and monasteries, which were numerous both in the city and suburbs; by far the greater majority were in ruins, but a few only partially destroyed were still tenanted by a few poor priests who, in spite of the Mahommedans, kept the incense burning before the gods of their forefathers. The massive stone gateways, richly carved roofs, and the elaborate decorations of the altars and images, afforded proofs of a high proficiency in art. Combinations of plants and birds furnished many of the designs of the decorations, executed either in well chiselled carvings or richly coloured paintings. In the carvings, dragons and monsters are frequent; all are generally coloured, the standard tints being red, blue, green, and yellow. The outsides of the principal walls are frequently decorated with medallion pictures of small animals and birds in black, grey, and white, alternating with squares or circles of complex geometrical figures. As far as could be judged from the images of the various deities, these temples appeared to be shrines of a compound of Buddhism, Taouism, and Confucianism, though no Buddhist priests were to be seen—or at least their yellow religious garb was nowhere visible—the priests having no distinctive costume, and living generally in their own houses in the suburbs. The images of the deities are nearly all life-sized, the place of honour being occupied sometimes by one, sometimes by three, seated on a pedestal in the centre of the principal hall. Around the central figures are disposed the statues of lesser deities, sages and scholars. In one temple where the central images were undoubtedly Buddhistic, the walls of the outer court were surrounded by fifty life-sized male and female figures, all seated, which seemed to represent the army of the Thagyameng. In another the chief deity was a colossal seated image, with a dragon at each knee, and the body of a snakelike dragon passing up under the double girdle, and breaking on the breast into a number of heads, recalling the seven-headed cobras of Hindoo mythology; the head and neck of a serpent-formed dragon issued, too, from under each armpit. Some of the female figures are seated on lions, other forms have the heads of bulls and birds, while four-armed figures also occur. In the khyoung, which formed our residence, there was a figure of Puang-ku, the creator, seated on a bed of leaves resembling those of the sacred padma or lotus. This remarkable four-armed figure was life size, and naked, save for garlands of leaves around the neck and loins. He was seated cross-legged like Buddha, the two uppermost arms stretched out, forming each a right angle. The right hand held a white disc and the left a red one. The two lower arms were in the attitude of carving, the right hand holding a mallet and the left a chisel. Except the Shuayduay images, which were of stone, almost all were constructed in the following manner: a frame of wood, making a sort of lay figure, is roughly put together, and afterwards padded to the proper proportions with layers of straw wound tightly over it; a layer of clay is plastered over the whole, and when dry, the flesh tints are laid on with marked realistic truth, and the garments duly coloured. The fact that the breast of every image of importance had been broken open seemed to show that a jewel or gold had been deposited therein, as is the custom in Burma.

During our stay the festival of the Goddess of Agriculture occurred. The stem of an iris and a branch of wild indigo were hung up over every door, and a general holiday observed; but nothing else marked the occasion, save that the priests insisted on kindling the incense in our khyoung, which act of devotion had been on other days pretermitted for the sake of our lungs. In one of the few khyoungs still inhabited by priests—all of which were situated in out-of-the-way places outside the town—I found a boys’ school conducted by an intelligent priest. A heavy shower of rain drove me in for refuge, and the master, who was seated at a low black desk, politely invited me to a seat. The pupils at once left their desks and crowded round us. A sign directing them to resume their desks and tasks was only so far obeyed that all began shouting their lessons at the full pitch of their voices; a word from the master, however, quickly dispersed them. I produced cheroots, and the priest sent for tea, and we chatted for an hour. Lying on the desk was a flat piece of wood like a gigantic paper-cutter. To explain its use, he called up a small boy, and, taking one of his hands, rubbed the palm with the instrument in a mysterious way. Suddenly, however, the paper-cutter rose and descended rapidly, tears started to the boy’s eyes, but were dried by a kindly word from the master, explaining that it was only an exhibition, not a punishment. The boys, whose ages varied from six to fifteen, seemed to enjoy their lessons there. The school hours lasted from nine to five o’clock, with an hour and a half’s interval, during which each boy purchased his dinner from a hawker of small bowls of Chinese dainties. Every boy has his own books, and, seated at a table, shouts his lesson aloud till he thinks he knows it, and then proceeds to attempt to recite it to the master, on whom he turns his back during the repetition. They learn to write at the same time as to read, for each boy first copies his lesson, getting the exact pronunciation of each letter and word from the master—thus whole books are committed to memory; but the babel of voices during the process is deafening, and the plan is not recommended for adoption to our school boards, although the punishment of the paper-knife might offer them a good model for imitation.

One bright little Momien boy was a great favourite; he was the pet son of the chief military officer, who brought him, as being deaf and dumb, in order to see what could be done. As the child attempted to imitate sounds, he was not deaf, and careful examination discovered that he was tongue-tied. A successful operation removed the impediment, much to the astonishment and delight of his father. The latter, whose title was Tah-zung-gyee, was a fine young Panthay soldier, of rather a jovial temperament. He invited us to a grand feast at his house, which was one of the few remaining uninjured within the walls. The invitation was duly conveyed to each on a piece of pink paper; and at the hour appointed—about 1 P.M.—a messenger arrived to inform us that the feast was ready. The house was approached through an outer court containing the stables. It formed a large square enclosing a central court. The principal building, facing the entrance, was raised on a terrace about four feet high, with a flight of steps at either end, each leading into an open hall. From this two doors led to the women’s apartments. The buildings on the other three sides of the square suggested Swiss cottages by their deep eaves and the large latticed windows of the second floor. A kitchen and store-rooms occupied the ground floor, and on one side was a dovecot. The eaves of the house were richly decorated with carvings representing landscapes with running water, bridges, and trees. A court outside contained a very choice garden filled with dwarf trees in vases; besides which, there were tall crimson hollyhocks and passion flowers. Two small stone tanks contained gold fish with remarkable doubly divided tails; and in one corner there was a model roughly carved in stone of a hillside, with caves and a pagoda. The walls of the rooms were decorated with Chinese landscapes and pictures of birds, in sepia and colours, which were mounted on rollers, like maps on a school-room wall. The entertainment, as usual, commenced with tea and cakes, followed by delicious nectarines and plums; after which came the more solid items of the repast. A decoction of samshoo seasoned with aromatic herbs was handed round like a loving-cup, our host first taking a vigorous pull, and passing it round till the jug was emptied. The liquid was warm and rather agreeable; but it fell to my lot to finish the contents, and, much to my disgust, I observed unmistakable pieces of pork fat among the herbs and spices. Our Mahommedan host not only drank samshoo, but allowed his drink to be thus flavoured with pork! He was most genial, and declared he would most willingly bestow his sisters on us as wives; and, in token of friendship, presented each with a jade ring and camellias. The women were curiously watching the strangers from the curtained doors; and towards the close of the evening the host asked for remedies for barrenness, with which some females of his household were affected. After some hesitation, the three patients mustered courage to show themselves, and were fine, young buxom women, with dwarfed feet. Some disappointment was evidently experienced at the refusal to prescribe for such patients as these.

The jealous reserve of the Chinese ladies was always pleasantly contrasted by the Shan manners, which united perfect modesty with a frank and pleasant demeanour. Thus the tsawbwa-gadaw of Muangtee visited us with her retinue of ladies. The old lady was splendidly attired, her towering turban being ornamented in front with the Panthay rosette of green, blue, and pink stones set in gold, and at the sides with little silver triangles set with small enamelled flowers. Her skirt was richly embroidered in silk and gold thread, and her light blue silk jacket was trimmed with black satin, which contrasted well with her massive gold bracelets. She wore amber and jade finger-rings, and a handsome silver chatelaine and richly embroidered fan-case hanging by her side. One of her maidens carried a small Chinese hookah, and another her embossed silver boxes of betel-nut, &c. She was greatly pleased with a present of a handsome carpet, needles, scissors, &c.; and her maids were charmed with small circular mirrors, which they at once fastened to their jackets as ornaments. These keenzas, as they called them, were immensely prized; and a few days after, as I was engaged in searching for land shells below the city wall, one of the Shan ladies hailed me from the battlements. The owner of the pretty face peering over the wall was evidently begging for something, which at first I thought was cheroots, and bade her by signs lower down her long head-dress, in the corner of which I tied a few cheroots, but these proved unsatisfactory; and the word keenza, keenza, at last made it plain that the young Shan lady wanted a mirror, and one had to be brought and sent up to her; and her glee was most amusing when she pulled up the cloth and found the keenza and a packet of needles. Compared to the pretty faces and picturesque attire of these Shan maidens, the dress and appearance of the Chinese women was very miserable. All the women who appeared in the streets were ugly and ill-clad, though the children had chubby, red cheeks. The majority wore pork-pie hats. All except the slaves had their feet dwarfed, and wore Dutch-like clogs in the rainy weather. The costume consisted of trousers, drawn tight round the ankle, a long loose blue garment, and a large blue double apron in front. Notwithstanding the dwarfed feet, the women walked to market three or four miles, carrying heavy loads, and seemed to think nothing of shouldering two buckets of water, slung to a bamboo. Every day our khyoung was besieged by crowds of beggars of all ages, from little ragged urchins to old men and women bent with age. Their rags and filth defied description, and sordid poverty in various degrees characterised all the wretched inhabitants of the ruined suburbs that surrounded the almost empty city. It must seem wearisome to harp upon the utter desolation and ruin that had resulted from the long continuous warfare, and the reader may prefer to gather some information as to the rebellious Mahommedan Chinese and their doings.