CHAPTER VI.

MANWYNE TO MOMIEN.

Departure from Ponsee—Valley of the Tapeng—A curious crowd—Our khyoung—Matins—The town of Manwyne—Visit to the haw—The tsawbwa-gadaw—An armed demonstration—Karahokah—Sanda—The chief and his grandson—Muangla—Shan burial-grounds—The Tahô—A murdered traveller—Mawphoo valley—Muangtee—Nantin—Valley of Nantin—The hot springs—Attacked by Chinese—Hawshuenshan volcano—Valley of Momien—Arrival at the city.

After various reports and interchange of letters between ourselves and the Panthays, tending to the removal of any doubts in the minds of the latter, we learned that the representatives of the Shan states had come to Manwyne. A slight hint of the unchanged ill-feeling of the Bhamô people was given in the imprisonment of Moung Mo, who had acted as guide to Williams and Stewart; a vigorous remonstrance, however, forwarded to the Woon, was followed by his liberation and return to the camp.

On the 8th of May, the Shan representatives arrived. The appearance of these fair, civilised, intelligent men, dressed in dark blue from shoe to turban, was a great relief. They assured us that we might go forward, and disowned having entertained any hostile feeling. Men were sent to Manwyne to bring mules, and our departure for that town on the next day but one was resolved on.

It was amusing to see the pawmine acting as cicerone, and exhibiting the wonders of our camp furniture to the inquiring Shans. They complained bitterly of the unsettled state of the country, and declared that our presence had already contributed to restore order. One of their complaints was that they could not trade with Bhamô on account of the extortion and plunder practised by the Woon and his people on the traders resorting thither.

The Ponsee pawmines were on their best behaviour, and even the vexed question of the mule hire was at last settled. The tsawbwa declared that every man, woman, and child, was the better for our stay, and entreated us to favour him by choosing this as the return route, and to make what use we liked of him.

The Shans came down very early on the morning of May 11th to announce that sufficient mules had arrived. We packed up with right good will, and at eight o’clock the mules actually appeared. At the last moment, “Death’s Head” pawmine attempted to create a disturbance about a photograph taken of his house. He declared his wife and son had been sick ever since, and that the photographer had bewitched them, in revenge for his having stolen our cow. Another pawmine demanded a toll of two rupees per mule, and threatened an embargo. This was too much. A short and sharp refusal, emphasized by a revolver, acted like magic, and the pawmines sneaked off, thoroughly crestfallen.

At half past eleven we started from the scene of our long detention. Scarcity of mules compelled us to leave our tents behind, and trust for future shelter to the hospitality of the townspeople en route.

The road was tolerably level for a mile or so, as far as Kingdoung, whence a steep descent led to a comparatively flat glen, closed in by hills on all sides but one, covered with flooded rice terraces, while here and there the ground was being broken up by men and boys with large hoes.

The steep descent to this alluvial hollow could be easily avoided by a road skirting a spur to the east, sloping down to the Tapeng. Here numerous small streams drain into the Tapeng, from both south and north, the largest of which is called the Thamô. From the north-eastern watershed, we obtained a fine view of the Tapeng valley, stretching away to the east-north-east, and then descended to the level of the river by a gradual slope, over rounded grassy hills and dried-up watercourses. On the way we were met by the tsawbwa-gadaw of Muang-gan, accompanied by a bevy of damsels offering cooked rice, fresh sheroo, and flowers. After a short halt for refreshment and friendly talk with the old lady, whose hospitality was duly rewarded with beads, we proceeded over a fair road six feet broad. From an eminence we viewed the Tapeng entering the hills through a narrow gloomy gorge, which swallowed up the broad placid stream, descending from the north-east between low white sandy banks. Looking up the river, the level valley stretched away, till in the far distance the border ranges, three or four miles apart in the foreground, seemed almost to meet. These defining mountains rose three thousand feet, and others of still greater height towered in the background, while a loftier range, running almost at right angles to them, crowned the far horizon. The level ground on either side of the river was parcelled out into innumerable rice fields, which, with the numerous villages situated on the higher undulations amid clumps of bamboo and fruit trees, attested the presence of a numerous and industrious population. The exposed reaches of sand within the river banks suggested heavy floods during the wet season; but at this period the water was drawn off by many canals, and glistened in little lakes, from which the green blades of the young rice crop were just raising their heads. The gentle slopes running up to the base of the hills and the lower hillsides afforded rich pasture to large herds of cattle and buffaloes. At the various villages large crowds of Shans and Chinese were gathered, awaiting the strangers. At one of some importance, mats were laid out for us under the trees, and we were challenged by the officials of Manwyne, who addressed our leader somewhat to this effect: “You say you are a man of authority, therefore we allow you to pass.” It was not etiquette to take any notice of them, and mounting their ponies, they fell into the rear of the cavalcade, with a crowd of boys behind them. Outside Manwyne itself a dense crowd of men, women, and children surrounded our baggage, which had been unloaded pell-mell on a stretch of sand where we were expected to encamp. No sooner had we dismounted than the crowd pressed around. They appeared by no means friendly, and the Chinese especially jeered and hooted, and one fellow had the impudence to feel the texture of the beard of one of our party. A more inquisitive set of sightseers it is impossible to conceive, and for some time they regularly blockaded us, almost to suffocation. While impatiently waiting for the officials in the full blaze of the afternoon sun, both parties found ample interest in surveying each other. To us the first sight of the peculiar but picturesque dress of the good-looking Shan women was probably as attractive as our physiognomies and attire seemed to be to the natives. The head-dress was a long blue turban, curled in crescent-shaped folds with neat precision, towering nearly a foot above the head, and inclined backwards in an inverted cone, displaying the back of the head adorned with large silver discs. Add to this, neat little white or blue jackets slashed with red, fastened with enamelled silver brooches, and exposing plump little arms adorned with heavy silver bracelets, blue petticoats with deeply embroidered silken borders, fanciful gaiters, and blue shoes, and the reader can imagine that the curious crowd of Manwyne was picturesque.

There was a good sprinkling of Chinese women with dwarfed feet, but they were much more poorly clad than the prosperous-looking Shans.

The men, Shan and Chinese, were all dressed in dark blue jackets and trousers, the Shans being distinguished by blue turbans with the pigtail wound into their coils, while the Chinese wore skull-caps. Almost all carried long-stemmed pipes. After some delay and expostulation with the headmen, we were inducted into a Buddhist khyoung or temple, standing in a separate courtyard just within the town, but entered through a gate of its own in the town wall. It was a low square building, facing the river, built partly of bricks and partly of wood, on a rubble foundation, and roofed with fired tiles.

It had two roofs, the upper in itself somewhat like a smaller khyoung perched on the top of the larger, with two latticed windows in each of its curved sides, and borne up by strong teak pillars. At either end two wooden partitions shut off the cells of the priests and their pupils. A kitchen in one corner completed the domestic arrangements, unless we may include two or three new coffins, and materials for more, piled ready in one corner of the verandah. A long table was covered with models of pagodas, enclosing seated figures of Gaudama, one principal Buddha occupying the centre, with an umbrella suspended over his head. This seemed to serve as an altar, on which two large candles were placed during the evening prayers, intoned with bell accompaniments, strongly reminding us of the Catholic mass. In the verandah three square niches faced this altar, one containing the image of a horse.

As soon as we had taken up our quarters, the temple was thronged inside and out by a curious crowd, who favoured us with their presence till we retired for the night. The ill-feeling of certain of the Chinese inhabitants was so dreaded by the headmen that an armed Shan guard was stationed round the khyoung, in addition to our own police sentries, who were requested by the authorities to be on the alert against an attack.

In the early morning the matin bell and chanting awoke us to find the apartment filled with precise old matrons and buxom Shan girls busy at their devotions. Each carried a little basket filled with rice, and a few brought offerings of flowers. As they entered, they first knelt in front of the principal Buddha, but did not venture on the raised platform. After a short prayer, they turned to the niche containing the horse, before which they repeated a prayer standing, and then deposited an offering of cooked rice in front of the quadruped. We next became the objects of their attention, but they were too timid to give us much of it on the first occasion. After the priests had finished their prayers, all the women arranged themselves in a row outside the khyoung. Presently the burly chief priest, draped in yellow, appeared. With downcast eyes and grave face he walked slowly down the line, holding a large bowl, in which each placed an offering of cooked rice. This done, the congregation dispersed to their homes.

This practice of the phoongyees gathering their daily food from the worshippers, instead of begging it from house to house, patta, or alms-bowl, in hand, is an instance of the unorthodox laxity prevailing among the Shan Buddhists.

A delay of two days was made necessary by consultations as to the route to be followed. The choice lay between crossing the river into the Muangla territory, or continuing along the right bank, through the Sanda state, to the town of that name. The latter was finally decided on, despite the opposition of a Muangla deputy named Kingain.

The town of Manwyne, or Manyen, was itself formerly a dependency of Sanda, but had been ceded to one of the Muangla family as the dowry of a Sanda princess. It is surrounded by a low wall of sun-dried bricks, raised on a lower course of rough stones. The population of Shans and Chinese might be reckoned at seven hundred, and the district contains about five thousand. At this time numerous fugitives from the more disturbed districts had taken refuge there, the war not having extended so far down the valley. The people, though prosperous, were lawless and independent, the nominal authority of the dowager tsawbwa-gadaw, or princess, being little regarded, and the Chinese power being in abeyance. We visited the bazaar held every morning outside the wall. The vendors were mostly girls, each sitting in front of a small basket, supporting a tray on which her stock was laid out. The eatables comprised a curious curd-like paste made from peas and beans, and in great request; peas which had sprouted, beans, onions, and various wild plums, cherries, and berries, while maize, rice, and barley, and several sorts of tobacco, were also on sale. One end of the bazaar was devoted to unbleached home-made cotton cloth, with a small stock of English piece goods, and red and green broadcloth.

Many Kakhyens, chiefly young women, were present, with firewood and short deal planks for sale, and we were struck by the perfect freedom enjoyed by these people as contrasted with their treatment in Burmese territory. The town gate led into a filthy narrow street, or rather lane, about nine feet wide. It was paved with boulders, and bordered on either side by a deep open gutter close under the windows, and alive with swine. The one-storied houses were built of bricks, with one room opening on the street, the sill of the open window serving as a counter, mainly for the sale of pork. This was the Chinese quarter; beyond it lay the clean Shan division, every house detached and surrounded by a neat little courtyard, with ponies, buffaloes, and implements, housed under substantial sheds. A few villages formed, as it were, suburbs of the so-called town, each enclosed in its bamboo fence, and intersected by narrow railed paths. None of the houses were raised on piles, as in Burma; the better sort were built of bricks and tiled, and the smaller ones were mere mud hovels. In one village we saw a man cutting tobacco for the use of the ladies, and were politely invited to be seated while we were instructed in the art of the tobacconist. The fresh leaves rolled firmly together were pushed through a circular hole in a wooden upright, and thin slices rapidly cut off; these are only partially dried and smoked while still green. Some was brought to fill the visitors’ pipes, and for half an hour we sat chatting to these homely Shans. Returning to the khyoung, we found it crowded with numerous patients, all entreating medical aid. The poor people were intensely grateful, though some of the old and infirm seemed to expect miracles, and went away evidently doubting the will, rather than the power, of the physician.

During this time our leader had been busily engaged adjusting the division of three hundred rupees among the Kakhyen pawmines; they were most demonstrative in their expressions of friendship, and urgently pressed us to confide ourselves to their escort on the return route. Presents were also distributed to the headmen of the town, and those of Sanda and Muangla, and the officials escorted us on a visit of ceremony to the tsawbwa-gadaw. Her haw, or palace, built in the Chinese style of telescopic courtyards, formed an enclosure in the centre of the town. We passed through two courtyards, the sides of the outer one forming the stables, and those of the inner one the kitchen and servants’ rooms, with the residence filling up the end. The entrance from the first to the second court formed a waiting-room, where a bench covered with silken draperies had been placed. After a few minutes we were invited to proceed through the second court to the house, which was raised about three feet from the ground, with an open reception hall, apparently off a third court, containing the private apartments. The reception court was laid out with flowers, dwarf yews, and a vine trained over a trellis. High-backed chairs with red cushions were set out, and presently the dowager appeared from her apartment, accompanied by some white-robed Buddhist nuns, or rahanees, and attended by three maids. One of the nuns was her daughter; the others had visited Rangoon, as pilgrims to the great pagoda, and brought back strong impressions of the excellence of British rule; both in Manwyne and elsewhere these pious ladies subsequently did good service by spreading favourable reports of the English visitors.

But we are forgetting the tsawbwa-gadaw. She was a stout little woman of fifty summers, of quiet self-possessed carriage. Above her round fair face towered a huge blue turban eighteen inches in height. Her costume consisted of a white jacket fastened with large square enamelled silver clasps, and a blue petticoat with richly embroidered silken border and broad silken stripes; her leggings and shoes were also covered with exquisite embroidery. She entered smoking a long silver-stemmed pipe, and received us with pleasant affability. Sladen held a long conversation with her concerning the mission, and she greatly rejoiced in the prospect of reopening Burmese trade, and promised her hearty support. Small cups of bitter tea, and saucers furnished with all requisites for betel-chewing, were handed round, the style of everything being thoroughly Chinese, and we took our leave, having evidently won her esteem.

The next morning, May 13th, the entire population of the neighbourhood assembled to see the visitors depart. The fair ones were in their holiday attire, their head-dresses decorated with sweet-smelling flowers. Many parting presents of these, accompanied with good-natured nods and smiles and kind wishes, were bestowed on the travellers. Several Shan officials accompanied us, perched high on huge red-cloth saddles and padded coverlids heaped on their small ponies. The route lay along the undulating right bank of the river, over a tolerable but narrow track, which crossed the mountain streams flowing into the Tapeng by substantial granite bridges, built of long slabs laid side by side, so as to form an exact semicircular arch.

About four miles from Manwyne, our attention was called to a number of men who rushed out of a village on the opposite bank of the river. Although they were all armed, and indulged in threatening shouts and gesticulations, we did not suspect any really hostile intentions. Presently, however, we found ourselves exactly opposite to them, when, whiz! came a bullet, passing close to Sladen’s pony, which plunged violently. At this they yelled, and fired some more shots, accompanied by furious brandishing of dahs. We took no notice, and this apparent indifference cooled their ardour, and the road, diverging from the river, soon took us out of sight. The fact that small but well-armed parties of Shans were posted at intervals suggested that the officials had expected an attack.

Beyond this the march to Sanda was an ovation, the people lining the road, and waving us on with shouts of Kara! kara! “Welcome! welcome!” Most striking was the panorama of the fertile and populous valley, with the broad Tapeng winding through it, and the magnificent wall of mountains towering on either hand. Village succeeded village, and every available acre was cultivated, the young rice now rising about two inches above the water, and tobacco plantations on the higher ground displaying their delicate verdure.

Halfway between Manwyne and Sanda, the road passes through Karahokah, the chief Chinese market-town of the valley. The village consists of two long parallel lines of houses separated by a broadway, down the centre of which the booths and stalls are placed on the weekly market-day. It was full market when we passed, so by advice we went round outside the village, but the curious crowd streamed out and nearly closed the road. A striking feature was added to the landscape by the bright red soil of the lower spurs jutting out from the higher range. In contrast to the dense forests above, they were almost destitute of trees, except at the extreme points, and clothed as they were with rich short grass, their strongly marked red and green colouring completed the unique beauty of the Sanda valley. At five o’clock P.M. we reached Sanda or Tsandah, seventy-five miles from Bhamô, and were conducted to a small temporary Buddhist khyoung built on the site of one wrecked by the Panthays.

It was little better than a thatched hut, with the ground for a floor. Here, as in other Shan towns, a striking difference was observed between the phoongyees and those seen in Burma. Their huge yellow turbans, coiled round yellow skull-caps, stood out each like a solid nimbus or glory. They wore white jackets and yellow trousers, girdles, and leggings, and shoes contrary to the precepts of their religion. Each carried on his back a broad-brimmed straw hat covered with green oiled silk. Their profusion of silver ornaments, buttons, rings, and pipes, was utterly at variance with the vows of poverty taken by Rahans.

The town of Sanda, marked on maps as Santa-fu, occupies the end of a ridge in a northerly bend or bay of the valley, a mile and a half from the Tapeng. The remains of a thick loopholed wall enclose an irregular area about six hundred yards square, over which are scattered eight hundred to one thousand houses, with a population of four to five thousand. We saw neither towers, pagodas, nor public buildings, save in ruins, excepting the tsawbwa’s house. The Panthays stormed the town in 1863, and the ruined defences and buildings had not yet been restored. Indeed the dejected and poverty-stricken inhabitants had only partially repaired their own brick-built dwellings.

Four hundred yards from the north-east gate was the bazaar, a village in itself, inhabited solely by Chinese, consisting, like Karahokah, of two lines of houses, the broadway between being closed at either end by a wall. A Chinese joss house, the ruins of which showed its former importance, stood near the entrance. In our wanderings through the bazaar, we met two women from the hills to the north of Sanda, of an entirely different race from Shans, Chinese, or Kakhyens, who called themselves Leesaws.

The next day was devoted to a ceremonious visit to the old tsawbwa. We entered his haw, a handsome structure of blue gneiss, through a triple archway, and passed through the courtyards, the whole building being arranged on the same plan as the Manwyne palace, but on a much larger and handsomer scale. High-backed Chinese chairs were duly set out in the vestibule of a building leading directly to the private apartments, and the courtyard in front was crowded with the leading townsmen. The tsawbwa, a frail old man with an intelligent face and polished manners, was dressed in a long coat of sombre Shan blue and a black satin skull-cap. He was nervous and silent, nearly all the talking being done by his officials, who seemed to be gentlemen of education and considerable intelligence. They were unanimous in expressing their hopes that our mission would result in settling the country and restoring the trade.

The little grandson and heir of the tsawbwa was brought to be introduced. The old chief evidently doated on the boy, and made a most urgent request, that Sladen would consider him as his son. When he learned that he already possessed a little boy, the chief exclaimed, “Then let them be brothers.” It appeared that the astrologers, in forecasting the event of our mission, had divined that this adoption by our leader was essential to the future welfare of the heir of Sanda. The interview closed with the circulation of tea and betel, and after we had requested the chief’s acceptance of a handsome table-cloth and other presents, we took our leave, but were followed to our quarters by servants of the tsawbwa bearing supplies of rice, ducks, fowls, and salted wild geese. The next morning the tsawbwa made his appearance, accompanied by his grandson, and bringing presents of a silken quilt and handsome embroidered Shan pillows. A richly enamelled silver pipe stem was given to Sladen in the name of his newly adopted son, for whom the grandfather earnestly besought his affection and care. At his request it was arranged that in leaving the town we should pass in front of the tsawbwa’s house. As the cavalcade neared the gates of the enclosure, two trumpeters stationed there blew a lusty flourish on their long brass trumpets. The chief himself stood on the steps, shaded by two large umbrellas, one a gold chatta and the other red, with heavy fringes. His chief men surrounded him, and the little grandson was held in the arms of an attendant. We dismounted to shake hands, which rather puzzled the chief. After a cordial parting, a salute of three guns was fired, and the trumpeters preceded us, blowing sonorous blasts till we passed through the south-eastern gate.

The road followed the embankments of the paddy fields, across the entrance to the high steep glen down which flows the Nam-Sanda stream, which was forded. A low red spur from the north-west range, nearly meeting another from the opposite range, here confines the Tapeng to a narrow deep channel, and divides the valley into two basins, one of Sanda and the other of Muangla. Having crossed this spur, we forded a small stream, which was quite warm, from its being fed by the hot springs of Sanda. The Muangla valley is a repetition of that of Sanda, with the same direction, and flanked by similar parallel heights, until the head of the basin is reached. There the valley, as it were, bifurcates: down the northerly division, the main stream of the Tapeng flows from the north-east through a fine valley, shut off from the Muangla basin by an intervening range of grassy hills. A large affluent, called the Tahô, or by the Chinese Sen-cha-ho, comes down from the east-north-east, between the high hills which appeared to bound the valley before us, but, opening farther on, enclose the valley of Nantin.

Numerous villages were passed, the inhabitants of which gave us a most hearty welcome. Near the head, or fork, of the valley, the Tapeng, even now a hundred yards wide, runs nearly across it, from one side to the other. We forded it at a village called Tamon, where a large bazaar was being held. Having crossed a slightly elevated flat peninsula on the left bank, and above the junction of the rivers, covered with charming villages embowered in high trees and splendid bamboo topes, we came to the Tahô flowing in broken streams in an old channel, a mile wide, between lofty banks. A great portion of the level ground is covered with rice fields, for the irrigation of which the streams are diverted.

A very neat bamboo pavilion had been erected for us on the high bank overlooking the Tahô, and after a rest, we crossed the channel to Muangla, which was visible on the opposite side, below a range of low red hills. We ascended the old river bank, and passed through the southern gateway, screened by a brick traverse, into a short broad street closed by a stone wall. Here we were conducted to a ruined Chinese temple, which had been hastily repaired for our occupancy, and were speedily invested by a crowd of curious folk, who seemed never satiated with staring.

Muangla, or Mynela, nearly ninety miles from Bhamô, stands on a high slope on the left bank of the Tapeng, enclosed by a brick wall nine feet high, with numerous loopholes and occasional guard-houses. The wall, with its six strong gateways, protected by traverses, appeared to be in much better condition than that of Sanda. With the exception of the broad bazaar street, the various roadways were mere lanes paved with boulders. The population within the walls could not exceed two thousand, which might be doubled by the addition of the large suburban villages close to the town. One of these contained the remains of some handsome Chinese temples, destroyed by the iconoclastic Panthays. One temple, built in a picturesque series of terraces, still retained evidence of its former grandeur in elaborate carving and colouring, a number of life-sized figures, and a large sweet-toned bell on the highest terrace. In still another, one of the courts contained a symbolic representation of the passage of souls into the future life. A miniature bridge with many passengers was depicted, guarded by two human forms, and spanning a miry hollow. In the latter, human beings were being tortured by monstrous dogs and serpents. Some of the passengers were represented being thrown from the bridge into this abyss; others had passed to Elysium, or Neibban, on the further bank. In another recess stood a low square hollow pillar with an opening on one side, facing a structure resembling a small brick stove with a chimney-like orifice, over which, as issuing from it, were depicted men and animals. This seemed intended to figure the transmigrations of the soul in the whirlpool of existences, from which every good Buddhist desires to escape into Neibban.

Close to the town, but out of sight of the buildings, we came upon the burial-ground of the tsawbwas, overlooking a desolate sea of hills. Over handsome horseshoe tombs with broad terraces and lofty portals of well-hewn gneiss, a few scattered pines stood sentinels. In the common graveyard, between the town and the junction of the river, as in many others passed in the valley, the graves are all raised and rounded as in old churchyards at home, lying to all points of the compass, with a broad stone slab at the head, but little care is shown except for the burial-places of the chiefs, in this particular the Shans differing altogether from the Chinese.

Viewed from Muangla, the western range of the valley culminates in a bold precipitous mountain, frowning above the Tapeng, which comes down through a narrow gorge between it and the hills which rise behind the town, and wall the valley of the Tahô. Above this narrow gorge, the Tapeng flows down a broad level valley, from its source reported to be three days’ journey distant. At its exit from the gorge, it is a quiet deep stream; at this spot a boat ferry was plying, and the view reminded us forcibly of Scottish mountain scenery. A long deep valley ran along the eastern face of the opposite hill, dotted on both sides by Kakhyen and Poloung villages and dark green forest. Its stream was conveyed across the Tapeng gorge by a wooden aqueduct, to irrigate the fields on the further bank. We were warned not to venture far from the town, so could not explore as much as we wished and had leisure for. A ceremonial visit had been duly paid on our arrival to the youthful tsawbwa, a lad of fifteen, who, under the regency of his mother, governed the extensive district of Muangla, paying a tribute of five thousand bushels of rice to the Panthays. The officials, who evidently favoured the old Chinese imperialist regime, demurred to our proceeding, for fear of the banditti infesting the road to Mawphoo. In this they were supported by the tsawbwa of Hotha, who joined us here, on his road to Momien, with a caravan of one hundred and fifty mules laden with cotton. He was a man of energy and education, speaking and writing both Shan and Chinese. As one of the largest traders between Bhamô and Momien, he possessed the respect and confidence of both Shans and Panthays. Sladen sent letters to the governors of Nantin and Momien, to which replies were brought on May 21st by our missing interpreter, Moung Shuay Yah, who was accompanied by three well-dressed and fine-looking Panthay officers, also by a guard sent to escort us to Momien.

On the 23rd of May, we left Muangla, and crossed the muddy flat to the Tahô, where the valley contracted to a breadth of scarcely two miles. Here we were joined by the Hotha chief with his well-appointed caravan, but a halt was called, as a report came in from the front that three hundred Chinese were ahead ready to attack us. Advancing to Nahlow, a little further on, a fresh report raised the numbers of the enemy to five hundred, and we were pressed to order a volley, which would frighten them away! At Nahlow the villagers pointed out a hill as the post of the Chinese, who had killed two men, but careful examination with field-glasses could detect no signs of the enemy. Some men were now observed a thousand yards ahead, and the Panthay officers galloped forward to reconnoitre. The mules were unloaded, and the villagers brought buckets of pea curd and fried peas strung on bamboo spathes. Our scouts having reported all clear, we proceeded over undulating boggy ground, and descended about eighty-five feet to the bed of the Tahô in a long oval basin, covered with gravel and boulders, and closed in on three sides by grassy hills. We presently came upon a man lying by the stream, with a frightful gash in his head, and a wound in his chest. He was a poor trader, who had been attacked, robbed, and, as it proved, murdered, for despite our help he died in a short time. At the head of the valley, a slippery zigzag path led up the steep face of a great spur of the Mawphoo mountain, the summit of which commanded a splendid prospect of the rich valley of the Tapeng, mantled with green paddy, and of the wild barren gorge below us. The sides of the parallel ranges, here a few hundred yards apart, were marked by large landslips, many of them white as snow. Our path lay along one which formed a perpendicular precipice five hundred feet above the Tahô. A high mountain facing Mawphoo was pointed out as the Shuemuelong, famous in the wars between Burma and China. From the summit, a level path turning north-east led us to Mawphoo, situated at the extremity of a high level basin, marked by two terraces on the northern side, with the Tahô flowing invisibly in a deep cleft, or ravine, at the base of the southern hills. At first sight one is inclined to regard it as an old lake basin, for it is so closed in by hills that the presence of the river could not be even suspected by a spectator who had not previously traced its course.

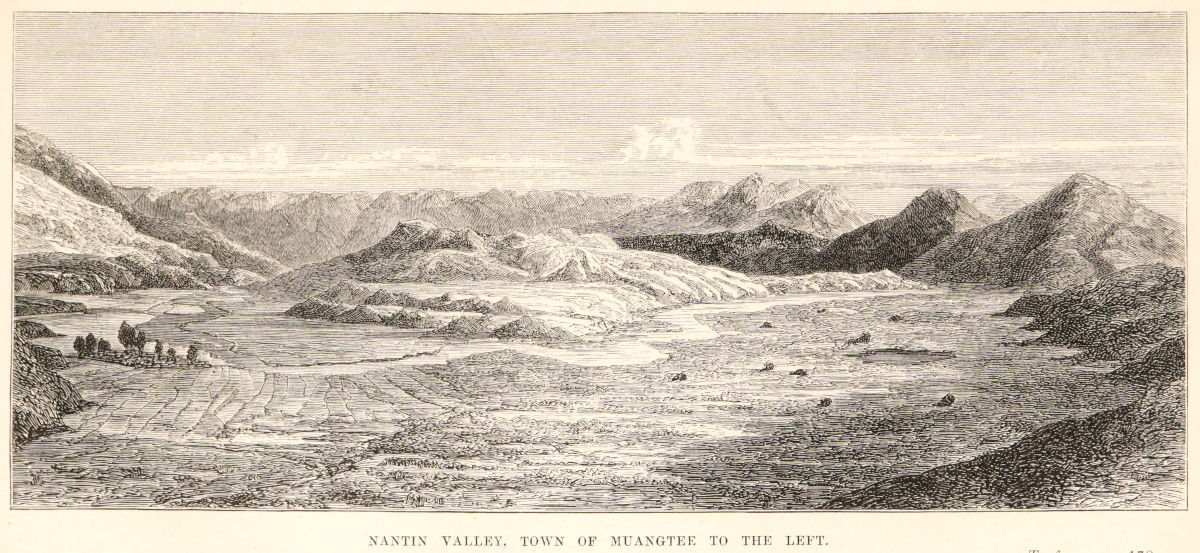

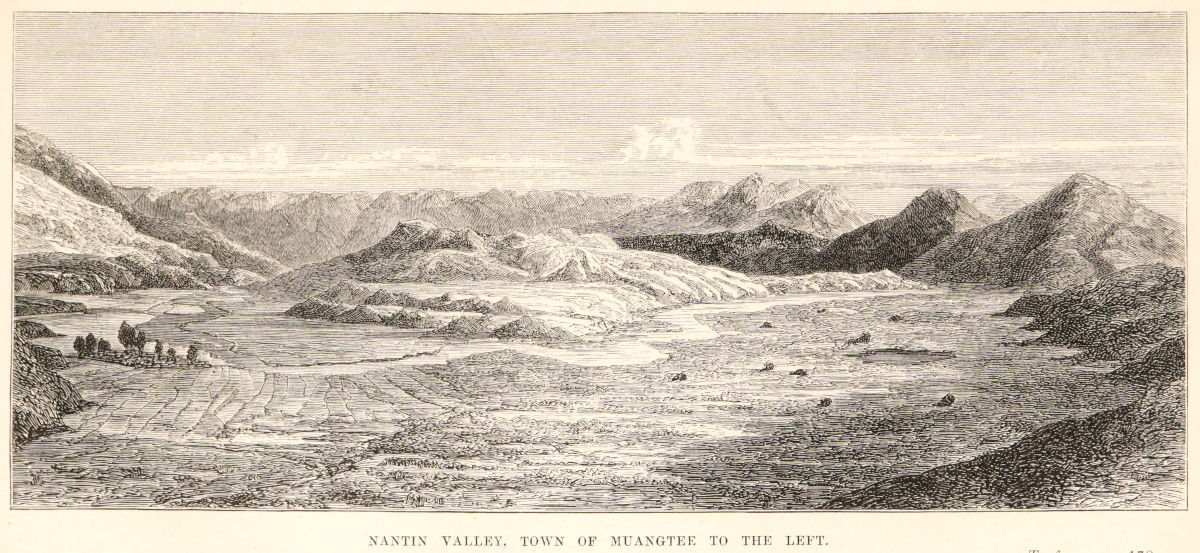

Mawphoo, which was said to have been recently the stronghold of Li-sieh-tai, was a wretched walled village in ruins, garrisoned by a few Panthay soldiers. The crumbling walls and ruins were overgrown with weeds and jungle, and it was hard to believe that this place had been held by an enemy and stormed only a few weeks before. From this the road skirted the level ground of the valley, but numerous deep watercourses presented frequent difficulties, while the rain of the last few days had rendered the path dangerously slippery. There was evidence however in the paved roadway, the numerous substantial stone bridges, and the frequent ruins of villages, that this must have been a considerable highway in peaceful times; now the whole country seemed to be a desolate waste. For some miles the heights along the road were manned by strong Panthay and Kakhyen guards, who carried a profusion of yellow and white flags, striped with various colours. All were armed with matchlocks, as well as spears and tridents mounted on shafts twelve feet long. Each picquet, as we passed, discharged their pieces, and then followed in our rear beating their gongs. At the end of this remarkable valley, we made a rapid descent to the treeless valley of Nantin, which now opened to view curving to the north-east or rather almost north. At the foot of the descent, the Tahô, which leaves the valley through a deep rocky gorge, is spanned by an iron chain suspension bridge, with massive stone buttresses, and an arched gateway on either bank. The span is about one hundred feet, and planks laid across the chains, covered with earth and straw, serve as a roadway, while one of the chains sweeps down from the top of the gateway, to serve as a railing. A small circular fort on an eminence was garrisoned by a few men, who guarded the bridge. We continued along the right bank through the Nantin valley, the sides of which presented three distinctly marked river terraces, and, having forded the river, entered the little Shan town of Muangtee, or Myne-tee, one hundred and eight miles from Bhamô. The walls were crowded, and the short narrow street through which we passed was thronged with women and children. Very few men were visible, owing, as we were informed, to the incessant fighting, which had killed off most of the male population.

NANTIN VALLEY, TOWN OF MUANGTEE TO THE LEFT.

A mile beyond we reached the small walled Chinese town of Nantin, now held by the Panthays. Two officers on ponies met and conducted us through the gate to a ruined Chinese temple. This had once been a handsome structure, but the walls were riddled with shot, the images defaced, and broken open in search of plunder. Nantin itself showed all the signs of having been once a thriving Chinese town. Now one-half of it was in ruins, and the other tenanted by a scanty and miserably poor population. By its position on a triangle of land between the Tahô and a swift deep affluent, with the hills rising close behind it and forming the base line, it completely commands the main road to Momien and Yunnan. It was accordingly held by a strong Panthay force, under a governor bearing the title of Tu-tu-du.

The governor visited us, accompanied by a Chinese chief named Thongwetshein, who had recently joined the Panthay cause. They demanded either a list of the presents intended for Momien or permission to search our baggage, both of which requests Sladen stoutly refused, and referred them to Momien for instructions. In the course of the day it came out that reports had been circulated that our boxes contained live dragons and serpents and fearful explosives. The fears of the Tu-tu-du were quieted by a peep at some bottled snakes and frogs, and he begged us to pay him an official visit. This, he said, would strengthen his influence over the townspeople, whom he described as thieves and ruffians.

A veritable Mahommedan Hadji was resident in the town. Knowing a little Persian and Arabic, he led the devotions of the faithful, the Musjid being held in his house. Our jemadar visited it, and described it as miserably appointed, without water for ablutions, and the worship as very lax.

The next day, we set out in state with a guard of eight sepoys, and preceded by two gold umbrellas. We passed through the bazaar, a narrow dirty street, with a double row of stalls, displaying hoes and ploughs, a little cloth, thread, paper, and eatables, including almost ripe peaches. At the residence, we were received with a salute of three guns; and the centre gates being thrown open for our admission, as a mark of special honour, we rode forward to the second courtyard. In the reception room the governor led us to a raised dais, he himself occupying a low place on a bench at the side of the room. After a few compliments, he suddenly vanished, only to reappear in a few minutes in full mandarin costume. The explanation was that, seeing Sladen in full staff uniform, he felt it incumbent on him to assume his official robes. Tea in beautiful porcelain cups and betel-nut were served; and Sladen having presented him with a musket and one hundred and fifty rounds of ammunition, the governor escorted us to the outer court, and dismissed us under a salute of three guns.

Instructions having come from Momien that we were to proceed without delay, we started the next morning. The Panthay garrison lined the street, and at a neat stone bridge spanning a burn which runs through the town the governor and Thongwetshein with their staff awaited us to say farewell, while the band struck up a lively air on the gongs. A guard preceded us, commanded by a nephew of the governor of Momien, and a more indescribable lot of irregulars were never seen. The officers, however, were fine intelligent men, well dressed in Panthay garb. So little fear of danger seemed to exist that they were accompanied by some female relatives in full Chinese costume, who rode in the advance guard. The valley, or rather glen, as it is only a mile wide, which stretched to the north before us, seemed to be a remarkable instance of the changes effected by water. Throughout its length of about twenty miles, its sides are marked by two well defined river terraces, and indications of a third higher one corresponding to the highest of the Mawphoo glen. These terraces close in at the head, while the entrance into the deep ravine of the Mawphoo glen terminates it. This whole length of area, lying one thousand feet above the level of Sanda, has been denuded by the Tahô; the second terrace, which corresponds with the lower one of the Mawphoo glen, is almost on the same elevation with a level platform which extends from the head of the valley. From this to the foot of the Mawphoo gorge seems to have been once a level flat, perhaps a lake, like that of Yunnan, from which the Tahô precipitated itself as a waterfall into the Sanda valley. The hills to the east, at the base of which our route lay, instead of the bold precipitous mountains of metamorphic rocks, were rounded trappean hills, occasional glimpses of which reminded us of home scenery, as they swept up in grassy curves, with dense clumps of trees on or near their summits. Numerous watercourses seamed their sides, the channels strewn with waterworn granite boulders, rounded lava-like masses of cellular basalt, and large fragments of peat.

The hills to the north-west rose much higher, in a lofty, well wooded mountain wall, with grander peaks soaring beyond. Seven miles from Nantin we halted to visit the famous hot springs. The steam rising from them had been visible nearly a mile off; and the Nam-mine, a rather large stream fed by them, was hot enough to startle both men and mules while fording it. The rocks composing the side of the hill whence the springs issue consisted of a cellular basalt and a hard quartzose rock, the former being partially superficial, and the latter that through which the springs issued.

Seen from the west, the south-eastern side of the hill is marked by an apparently deep, crater-like hollow, forcibly suggesting that it was once a volcanic vent, the neighbouring rocks being almost scoriaceous, and the internal heat being still evidenced by the boiling springs. Besides those on the western face, others still larger occur on its other side, some miles to the east. Of those visible, the most important is an oval basin about three yards long, with a depth of eight inches; about six yards from it are a number of funnels, six inches in diameter, in the quartz rock, emitting steam. Higher up, and fifty yards off, another strong jet of steam occurs, and on the other side of a narrow gully are two other springs, which emit a considerable body of boiling water through the earthy face of the hill. The water in the principal spring comes up with great force through circular apertures, about three inches in diameter, and the bottom of the basin is covered with thick impalpable white mud. Owing to the heat and volume of steam, it was only accessible on the leeward side, and the ground was so hot that our barefooted followers could not approach by some yards. It vibrated in a remarkable way, and the sensation was as if one were standing over a gigantic boiler buried in the earth, which was increased by the loud roar of the steam from the funnels, and the indistinct rumbling noises in the hidden inferno.

It is remarkable that, although the steam is at scalding heat, the stones in it are covered with masses of green jelly, which thrive at a temperature only ten degrees below boiling-point. The analysis of a gallon of the water is as follows: 120 grains of solid matter; 112 salts of alkalis, almost entirely chloride of sodium; 80 earthy salts, silica, and oxide of iron. No nitric and but very little sulphuric and carbonic acids were present, but traces of phosphoric acid were detected. We were informed that the springs are much resorted to by patients from all parts, who use the spring to cook their food, and cure themselves in the vapour or the Nam-mine stream. After enjoying our halt, which had been made with the full approval of the Panthay officers and the Hotha chief, we started to overtake the cavalcade, which had marched forward. Just as we rejoined the rear-guard, four shots were fired in front, but as the road only admitted of single file, and lay along a thickly wooded hillside, marked by the ruins of many villages, no one could advance to reconnoitre. Word was presently passed down that the mules had been attacked and two Panthay officers wounded; but on proceeding onwards, we discovered that the affair was more serious, and that the two officers and another man had been killed. We soon came up to the bodies of the officers wrapped in their large turbans and tied to bamboos, ready to be carried back to Nantin. The poor fellows had both been great favourites with their comrades and the governor of Momien; and a sad group surrounded the bodies, including their female relatives, who had ridden out from Nantin only to lament their murder, for so it was. As they were riding at the head of the mules, at a corner in the narrow path, a lurking body of Chinese rushed out from the trees, shot down the first, and the second, hurrying to the rescue, was shot through the leg and cut down with a dah. Eight mules had their loads thrown off and looted, and were then driven up the hills. A little further on, the scene of the disaster was marked by the ransacked packages lying on the roadside, and among them two boxes containing my clothes and notebooks. One of these had escaped unopened, and was left in charge of a Panthay officer, who promised to see it brought on. At the head of the valley a halt was called, to enable all the Panthays to come up, as a second ambuscade was suspected in a thickly wooded hollow in the steep hillside above.

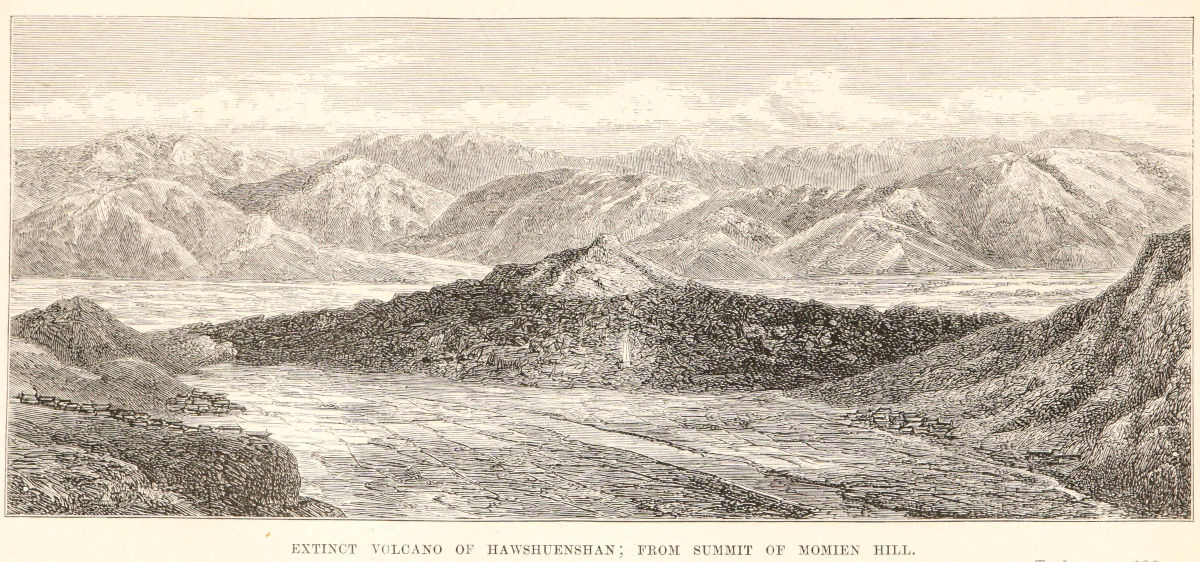

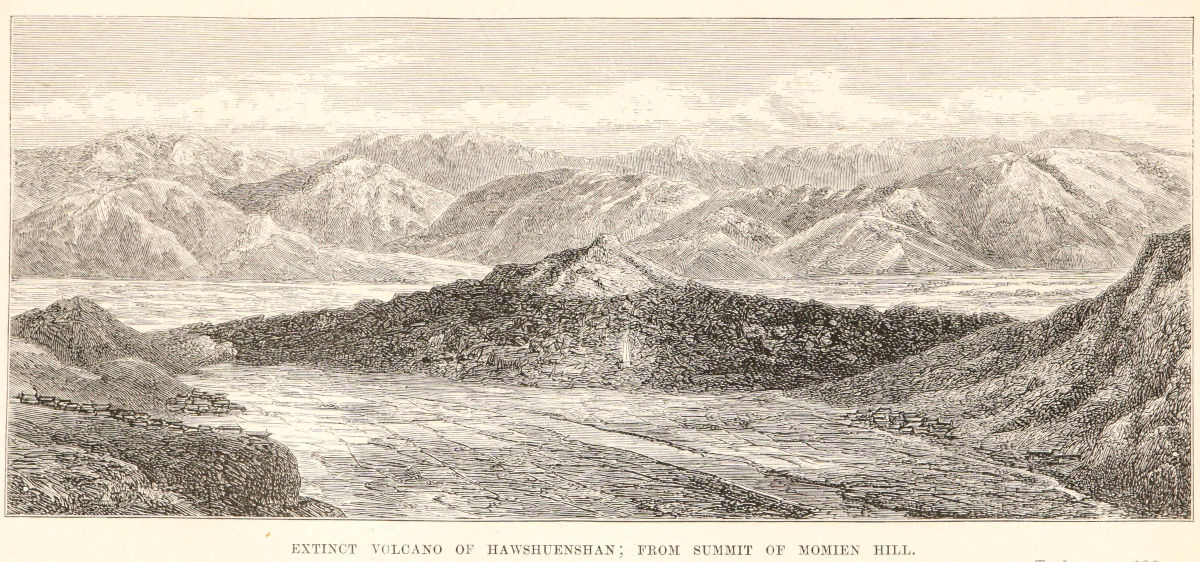

At this point the river terraces sweep round to form the head of the valley, but the Tahô has cut a deep gorge through them. The second terrace could be seen continuing to the north in a long upward slope, thrown into rounded mounds, the sites of small villages, and terminating in a distant broad plain. The hillsides were covered with pines, and the road ran through a belt of dense forest, over the shoulder of a spur from the main range of hills. Here the attack was expected to be made, so we advanced with vigilant attention to the jungle on either hand, passing ruined villages, buried in dense vegetation, consisting chiefly of fruit trees and garden plants run wild. We were unmolested, and, after a short descent, came upon the Tahô foaming along its rocky channel, spanned by a broad parapeted bridge of gneiss and granite. The roadway exactly followed the curve of the arch, and the ponies could scarcely keep their footing on the smooth slabs, worn almost to a polish by the constant traffic of bygone centuries. On the right bank a small Panthay guard met us, and reported that they had chased a body of Chinese, lurking in the dreaded hollow. We soon gained the level of the plain, seen in the distance as the upward termination of the Nantin valley. From its eastern side rose a long conical hill, stretching nearly north and south, in a black sterile mass of lava, with the exception of its rounded grassy summit. This remarkable extinct volcano of Hawshuenshan, rising abruptly from the plain, stands out in striking contrast to the tumulus-shaped grassy hills which cluster round it on all sides. A few small plants rooted in the interstices of the rocks do not, in the distance, impart even a trace of verdure to its barren sides, which are thrown into long rocky curves, evidently old lava streams. We rode over the eastern extremity of this volcano, by a broad path paved with long slabs of gneiss and granite, and again came upon the Tahô, as a narrow rapid stream running between it and the abrupt sides of the grassy hills to the east. We crossed the river over another handsome stone bridge, and passed the ruins of a rather large village. The Tahô issues at this point from between a high spur and the volcano, through a very narrow gorge; and the road wound up the side of the spur, and was laid with a double line of stone flags to facilitate the ascent. From the top we gained a fine view of the small circular lake-like valley, from which the Tahô issued below, and looked down on numerous villages encircling the irrigated level in its centre, which was covered with young rice. Continuing a slight ascent over the grassy hills, by a good broad road, we turned the flank of a lofty hill crowned with a white pagoda; and the valley of Momien lay before us, shut in on all sides by rounded hills, treeless, but covered with pasture.

EXTINCT VOLCANO OF HAWSHUENSHAN; FROM SUMMIT OF MOMIEN HILL.

The hills seemed to slope almost to the walls of the city in the centre, but the intervening area was sufficient for an almost unbroken ring of large villages, either in ruins or deserted. To the right rose the Deebay range, beyond which lay the road to Tali-fu, and in the far distance the lofty Tayshan ranges, running north and south, formed a noble background of black rugged mountains. A long narrow valley stretched in a northerly direction, marking the course of the Tahô, from its source in the Sin-hai or Pai-hai watershed, sixty miles distant. Between the foot of the hill and the city wall, a long line of flags of all shapes and colours, and glittering spears, marked the presence of the Tah-sa-kon of Momien. An aide-de-camp presently arrived with a request that we would dismount and greet the governor, who had come out to meet us. We were a motley group, not improved in appearance by twenty-one miles’ march over muddy flats and dusty hills, but, preceded by the most presentable sepoys, with the jemadar carrying a gold sword in front, the three Europeans advanced under the canopy of two gold umbrellas, through a long line of officers and banner men, to the Tah-sa-kon, who, dressed in full mandarin costume, occupied a richly cushioned chair, with three huge red silk umbrellas, fringed with gold lace, held over him. He rose to welcome us with handshaking and courteous greeting, and then escorted us to a large, well-built temple outside the town wall, but close beneath the angle where the governor’s palace stood. Here we took up our quarters with a sense of profound satisfaction at having at last, after so many delays and difficulties, reached a city of Western Yunnan.