CHAPTER IX.

THE SANDA VALLEY.

Departure from Momien—Robbers surprised—At Nantin—Our ponies stolen—We slide to Muangla—A pleasant meeting—The Tapeng ferrymen—A valley landscape—Negotiations at Sanda—The Leesaws—A Shan cottage—Buddhist khyoungs—For fear of the nats—The limestone hill—Hot springs of Sanda—The footprint of Buddha—A priestly thief—The excommunication—The chief’s farewell—Floods and landslips—Manwyne priests—A Shan dinner party—The nunnery—Departure from Manwyne—The Slough of Despond.

At the last our departure from Momien seemed doubtful, owing to the difficulty of finding porters, and men were forcibly impressed into the service. Any demur as to a particular box or complaint of the weight of their loads was silenced by a torrent of abuse from the Panthays, who, to these persuasives, sometimes added severe blows. About 8 A.M. on July 13th we started, waving our adieus to the governor, who had come out on the town wall to bid us farewell. The guard gave him a feeble cheer in Hindustani, which they again repeated as we marched out of the bazaar gate and set our faces westwards. Two Panthay officers, who had been our constant visitors, accompanied us for nearly a mile, and at parting they burst into tears. After we had gone a long way, and turned back to take a last look at Momien, we saw the two figures, standing on the same spot, gazing wistfully after us.

In a short time it began to rain in torrents, and the roads became very slippery, especially for men carrying heavy loads, so that we soon went ahead of the porters. At the descent into the Nantin valley, the road was as if it had been well oiled. Ponies and pedestrians slid down the steep hill-path in wild confusion, many of the party coming to serious grief. A little Chinese girl, who had been presented to the jemadar and his wife, as a return for his exertions in the mosque services, accompanied us, tied in a small bamboo chair on a pony. As the beast was quite at liberty to choose his own course, the terror and screams of the small neophyte were most piteous. At the scene of the attack made on the upward journey—marked still by some of our empty boxes—we passed the bodies of two men who had been recently killed and cast on the roadside. Halting at the hot spring to wait for the porters, we learned that these were the corpses of Chinese robbers, who had been caught, by the Panthay vanguard, crouching in the jungle with long spears, ready to stick the first mule passing, and had been summarily disposed of by them. Near Nantin all were requested to wait and allow the rear-guard to close up, as we were about to pass a favourite lurking-place for robbers.

We formed a long line, with Panthay soldiers before and behind, and, with gongs beating ahead, marched unscathed into Nantin, which was reached by six o’clock. Our former residence, the khyoung, was found to be already tenanted by a Panthay guard and a Kakhyen tsawbwa groaning with fever. A dose of sulphate of magnesia, followed up with quinine, secured to him sleep and to ourselves quiet, as far as he was concerned; but we were kept on the look-out, as the baggage arrived in detachments, much of it, including bedding, not turning up till the next day, and some articles, such as a portable bedstead, and a magazine box, not appearing at all. The governor came to greet us in the evening, attended by a guard, one of whom carried a huge gauze lantern swung from a tripod. He was full of regrets that he had not been apprised of our coming, so as to have prepared comfortable quarters, and met us on the way. The Hotha tsawbwa did not appear, according to his promise, and was reported to be still in his own valley, and his absence prevented us from adopting the embassy route across Shuemuelong into Hotha valley. As it afterwards appeared that the irrepressible Li-sieh-tai and his troops had taken up their quarters in a strong post on the Shuemuelong mountain, it was just as well that this route was not attempted. We found ourselves accordingly obliged to retrace the former road to Muangla, Sanda, and Manwyne.

The pleasing news reached us that a party of one hundred Burmese had arrived in Muangla, sent from Bhamô in charge of a remittance of five thousand rupees, and to escort us back to that place; so that, notwithstanding all the discomforts of our quarters, all turned in well pleased and prepared to make an early start for Muangla.

Our morning slumbers were rudely broken by one of the police, who reported concisely, “Of the three ponies, not one is left.” During the night thieves had made a hole in the wall of the courtyard just large enough to admit the passage of a pony, and through this the animals had been carried off unperceived by the sentries posted within twenty yards. Examination showed that the animals had been supplied with corn, and a trail of grain led to another opening in the town wall. On the previous visit we had been cautioned to watch carefully against any attempt to steal the ponies; but the warning had unfortunately been forgotten. A robbery had been attempted in the same way when the tah-sa-kon was residing in the khyoung. The thieves purloined a gun and sword, but an alarm was raised, and the latter was dropped in their flight. We borrowed ponies to carry us to Muangla, and started at half past ten. As before, considerable difficulty was caused by the absence of porters, nearly all the coolies from Momien having run away. Mules had to be found to supply their place, and the proverbial character of these beasts was fully verified by those of Nantin, which for an hour stubbornly refused to be loaded. During this interlude the Panthays were doing their best to impress men for the lighter loads. The recusants were dragged up by soldiers with drawn swords, and each, when loaded, was followed by a spearman, ready to egg him on with his spear if he attempted to lag behind. As we passed through Muangtee, the townspeople had all turned out, and our old friend, the tsawbwa-gadaw, and her retainers, male and female, stood outside her haw, and waved salutes and adieus. Outside the town a strong Shan guard of honour was drawn up, and escorted us to the chain bridge across the Tahô, three miles from the town.

During the rains the river is unfordable, and the road follows the left bank along the embankments of the paddy fields as far as the bridge. From the right bank the ascent to the lofty Mawphoo glen proved most arduous, the road being so slippery that men and beasts were continually falling, and many of the pedestrians were severely bruised. It rained incessantly, and it was a great relief to all when Mawphoo was reached, and an hour’s rest was enjoyed previous to the descent into the head of the Muangla valley. The road first led down a declivity, where the only mode of progress for the ponies was by sliding; and then followed a series of zigzags, some of them over frightful precipices, where a slip of the pony’s foot would be certain destruction. At this season the Tahô issues as a tremendous torrent from the deep gorge in the Mawphoo hills, and the distant Tapeng appeared almost as large as the Irawady in dry weather. We reached Muangla at dusk, and were astonished, on entering the town, to meet an Englishman, accompanied by some Shans. He rushed up to our leader, and introduced himself as Mr. Gordon, a civil engineer from Prome, who had been sent by the Chief Commissioner with additional funds, and to fill the post of engineer to the expedition. He had received his instructions by telegraph on May 9th, to follow the party as quickly as possible, and had obeyed them with laudable energy. He had travelled from Bhamô with a guard of fifty Burmans, and found no difficulty en route. At Manwyne he had met with the Hotha tsawbwa, who wished him to remain for a day or two; but pushing on, and passing Sanda without halting, he had reached Muangla the day of our arrival. The guard of one hundred Burmese which had been despatched in charge of the first supply of rupees had arrived there ten days previously; but the tsare-daw-gyee in charge had been afraid to advance further.

From this place our Panthay guards were to return, and the Burmese officer expected that his escort would take their place. He seemed indeed most eager to be of service, and was much chagrined when he learned our leader’s intention of exploring the route on the southern banks of the Tapeng. It was a most pleasant surprise to meet Mr. Gordon, whose goodwill and energy were inexhaustible. The supply of funds also came just in time to enable us to make complete collections of Shan products, and it also marvellously smoothed the difficulties of the return journey. So we set out from Muangla in excellent spirits, notwithstanding the incessant rain. Messages had come, from parties unknown, offering to restore the stolen ponies for three hundred and twenty rupees, but as the local authorities did not seem inclined to move in the matter, the thieves were left in possession of their booty. Our Mahommedan escort bade us farewell with evident reluctance, and one officer expressed a strong desire to accompany us to Rangoon, saying that if he was once there, he would never return to Yunnan.

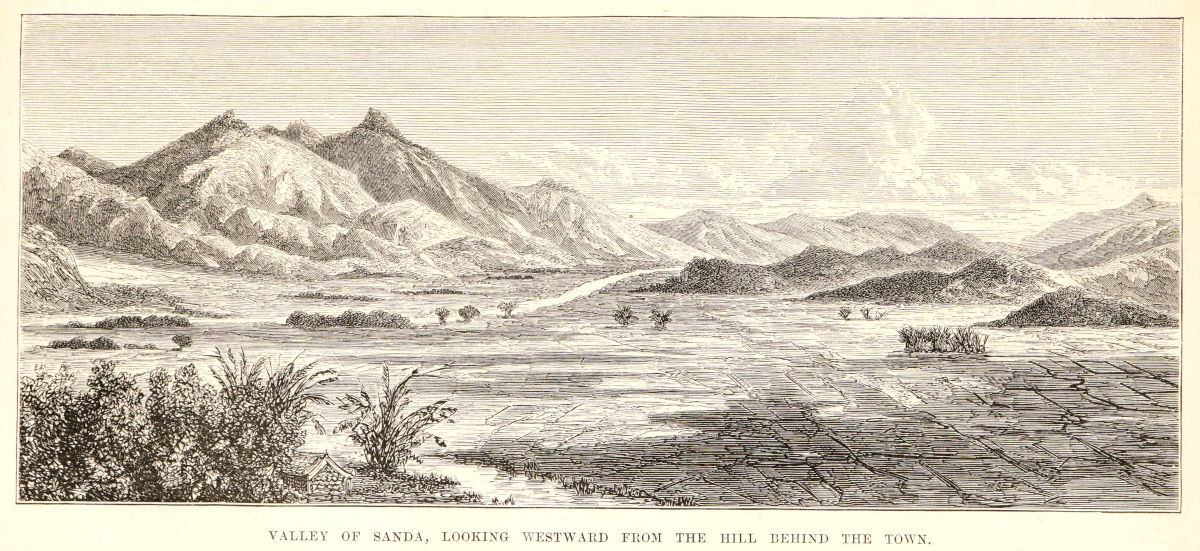

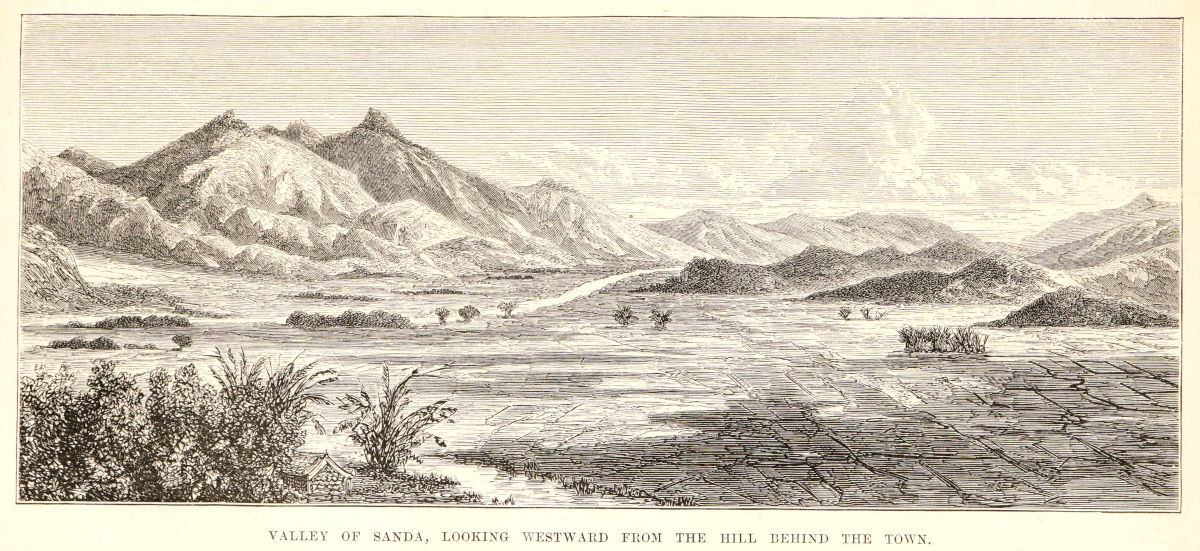

On July 20th we started for Sanda, the usual difficulty as to porters having compelled me to leave behind the collecting boxes for specimens, with two of my collectors in charge, until carriage could be procured. We crossed the Tapeng above its junction with the Tahô in ferry-boats, the boatmen at first refusing to convey us unless paid five thousand cash beforehand. This attempt at extortion was resisted, and the dispute was ended by our taking forcible possession of the boats, when the boatmen at once gave in, and worked with perfect goodwill and activity till all the party were safely over. We then set out in a body for Sanda, the road at first leading along the top of some old river terraces deeply channelled by mountain streams, which were crossed by two narrow planks laid side by side. Our ponies, however, crossed them with ease, except the one which Gordon had brought from the plains, and which was unused to such acrobatic exploits; so it grew nervous on a bridge over which it was being led, and disappeared head-over-heels in the deep gully beneath. Wonderful to relate, the animal broke no limbs, and shortly reappeared a little further down, trembling, but unhurt, on the river terrace below. Two miles beyond the place where the Tapeng had been forded on the upward journey we descended towards the level centre of the valley, at this season under water, the road being carried along a substantial embankment built to keep back the floods. The whole extent of the valley was clothed in exquisitely fresh verdure, in beautiful contrast to the dark mountains which towered like a protecting wall on either side, while alternate cloud and sunshine fully displayed the beauty of the landscape. Now deep shadows of giant clouds flitted down the mountains and over the sunny plains, while occasional fleecy mists wrapt the highest peaks, and again black storms obscured the hills as with a curtain,

“Lashed at the base with slanting storm,”

the rest of the valley basking in the sunlight. Near Sanda a stream had to be crossed so swollen that the ponies could scarcely stem the current, which was over the saddles. By 6 P.M. we were safely housed in our old quarters at Sanda, and the tsawbwa’s headman speedily arrived with a supply of fowls, rice, and firewood sufficient for all our wants.

VALLEY OF SANDA, LOOKING WESTWARD FROM THE HILL BEHIND THE TOWN.

On awaking in the morning, we made the unpleasant discovery that two packages had been stolen from our bedsides. One was only a fishing-rod and bamboo pipe and stems, but the other contained the solid silver pipe-stem given by the tsawbwa to Sladen, and some other presents. The theft was duly reported to the tsawbwa, who at once offered two hundred rupees’ reward for the recovery of the stolen articles. During the day, many people crowded the khyoung, having clothes and ornaments to sell. The priests were much scandalised to see women’s clothes sold and exhibited in the sacred precincts, and at last procured an order from the tsawbwa, forbidding the women to come for the purpose of such traffic.

We remained at Sanda till July 8th, being detained partly by the rain, and partly by negotiations with the people of the Muangla district, lying on the other side of the Tapeng, relative to our homeward route. The chief persons, a village headman named Kingain, and the poogain of Manhleo, a place opposite to Manwyne, through whose jurisdiction the route lay, had both been hostile to us on the upward journey. The Hotha tsawbwa himself proved to have had some dispute with the Sanda people, which prevented his coming to meet us, while the Sanda headmen were averse to our crossing over to Hotha, for fear any future trade should be diverted from their town. In the course of the negotiations, two Shan headmen of villages informed Sladen that they could conduct us safely by a good and easy hill road to the Molay river, which could be reached in two days, at a point whence it was navigable during the floods, for large salt boats, down to the Irawady.

The skilful patience of our leader was at last rewarded by converting Kingain and the Manhleo poogain into firm friends, and it was settled that we should proceed to Manwyne, and cross the river at that place, whence they would secure our safety. The son of the poogain arrived to act as our conductor, and a letter was received from the Hotha tsawbwa, promising to meet us at Manwyne.

During our stay we had unrestricted opportunities of viewing Shan manners. Every fifth day the regular market was held, and the broad street was crowded by the country folk. Stalls lined both sides of the roadway, which seemed paved with umbrella-like straw hats. Besides Kakhyens from the hills, Leesaws were numerous, bringing oil, bamboos, and firewood for sale. Both men and women shave a circle round the head, leaving only a large patch on the upper and back parts, from which the hair is gathered into a short pigtail. Both sexes dress so much alike that the boys and girls were almost indistinguishable from each other. Some of them were induced to pay us a visit, and give words and phrases of their language, which seemed to be quite distinct from the Kakhyen tongue, and somewhat akin to the Burmese.

Seeing our interest in these people, a respectable old Shan, who had already done some trade with us, invited us to his house, where he professed to have some Leesaw clothing to dispose of. It turned out that he proposed to pass off his own old clothes on the gullible strangers; so our visit became one of politeness only. We were duly seated, and his daughters served us with sliced mangoes and plums, which were eaten with salt. Our host’s two wives were present, and other matrons flocked in from the neighbouring cottages, their hands blue with indigo. We asked if it was usual for Shans to have more than one wife, and were told that it was not, but that every man pleased himself. We also learned that the usual age for marriage is between eighteen and twenty, and the consent of the parents alone is required to make the contract binding, as there is no religious ceremony, and the priests have no voice whatever in the matter.

The house, like all the Shan cottages, was enclosed in a courtyard, and consisted of three rooms—a central living-room, with a sleeping-room on either side. Against the wall of the “keeping-room,” facing the door, stood the family altar, a small table having on it an incense vase and an ancestral tablet. A broad verandah ran along the front of the cottage, at one end of which stood a large indigo vat, hollowed out of a solid block. From this house we visited the Shan and Chinese khyoungs. Both were plain bamboo structures, built on the sites of the former buildings, described as having been rich and splendid structures, destroyed by the Panthays some years previously. The Shan temple contained only one figure of Gaudama, and as the phoongyees were seated at their rice, round a small bamboo table, we went on to that of the Chinese, next door. Here there was one principal Buddha, clothed in a yellow robe, and crowned with a nimbus resembling ostrich plumes. On the altar were a few small Buddhas freshly gilded, and a number of old pictures. On a small table was a wooden fish, such as was of frequent occurrence in the Momien khyoungs. Tradition says that in one of his former existences Gaudama was shipwrecked, but brought to land by a large fish, which he afterwards fed during its life. A strange mixture of Arion and Jonah pervades this legend; but the fish is probably a mystic legacy from the more ancient religions to which Kwan-yin and other deities belong. The chief phoongyee was very courteous, and had seats brought covered with red rugs, while his waiting-man served the guests with tea and fruit. He exhibited a number of pictures representing the judgment and punishment of sinners. One figure, evidently the judge, was seated at a table, with a book before him, and pens and ink-horn at his side, while two figures stood on either hand—one a hideous-looking monster, the other of more human and gentle aspect. The latter was the good, the former the bad recording angel. In front of the judge, the pious and wicked were depicted, in fleshly forms, departing to their several destinations. Of the latter, some were being dragged away by devils; while others in the foreground were being subjected to torments appropriate to their failings in life. The possessor of a false tongue was having it torn out by the roots, while the slayer of animals was being hacked in two, with his head downwards and his legs wide apart.

There was a grotesque humour about these horrible pictures, which made even the priest smile, as he exhibited and described them; but he waxed very grave as he told of the former splendour of the ruined religious edifices of Sanda.

There was little to be done in the way of collecting zoological specimens, and nothing in the way of sport. A thick grove of fir-trees, marking the burial-place of the tsawbwa’s family, was the only covert, but firing there was looked upon as certain to bring disease and death upon the chief and his household. After one attempt, a formal request was made that we would not shoot on the hills behind the town. A nat is said to dwell in a cutting, which marks the entrenchments made by the Chinese army in 1767, and the Shans believe that if a gun were fired, the insulted demon would come down as a tiger and carry off children. The chief himself came one day complaining of cough and headache, and asking for medicine to dislodge the nat who had seized him, but sulphate of magnesia proved too much for the demon. A Burman assistant surveyor, who had been sent to make a survey of the river, was prevented by the villagers, who pleaded a dread of the nats’ anger, and the tsawbwa, when appealed to, not only supported this view, but privately asked the interpreter if we had not a secret object in examining the country, and did not mean to return next year with a strong force to take possession. We were perfectly free to stroll about the environs, and one of the chief men undertook to guide us to visit the hill whence the lime sold in the market was procured. The road lay along the paddy fields, and was either knee-deep in mud or up to the saddle-girths in water. We crossed the Nam-Sanda, a deep strong stream flowing from the north through a short narrow glen, on the other side of which the limestone hill rose in a gentle declivity. As we rode through the fields of cotton, now in flower, and kept so clean that not a weed was visible, Shan girls, dressed in dark blue, with short trousers and petticoats with little aprons over them, looked up from their field-work with mute astonishment depicted on their round chubby faces. About four hundred feet up the grassy hill, on which not a tree was to be seen, the bluish-grey masses of hard crystalline limestone occur, lying in irregular heaps overgrown with long grass, as they have fallen down from the rocky heights above. Some superstitious ideas are attached to the occurrence of the limestone in this place, and it was shown to us as a supernatural curiosity. The masses are dug out of the ground, and carried to the villages, where they are calcined, grass being used as fuel in preference to wood. An old kiln was shown us, which had been formerly erected by some Chinese lime-burners, who had come from Tali-fu. On our return, the tsawbwa was anxious to know if the hill contained silver, the Shans having the impression that our field-glasses enable us to see into the very heart of the mountains and detect the precious metals therein concealed. In the bed of a small stream running down the little valley, the hot springs occur, consisting of two separate groups, separated by about a quarter of a mile. In the most easterly, we found only one spring, in a basin about six inches deep and a yard in diameter; the water bubbles up through a gravelly bottom, over which a fine black micaceous mud has been deposited. We found the temperature to be 204°, two degrees below the boiling-point of Sanda, viz. 206°; but in the cold weather, when undisturbed by floods, the temperature is higher. As a proof of this, we saw the feathers of fowls and hair of kids, which had been cooked in the spring, lying all about the banks of the rivulet. The natives deepen the basin by piling stones round its margin, and use the spring as a medicinal bath, and sometimes drink the waters. The other group had five openings, through which the water bubbled up in the bed of the stream, which had been diverted to expose them. All the basins but one had been obliterated by the floods, and the temperature of the water much reduced; but by inserting the bulb into the holes, the temperature was found to be the same as that of the first spring. The atmosphere round the springs was sensibly warm, and the ground so hot in some places that our barefooted companions could not stand on it. A peculiar heavy smell was perceptible, which was also perceived, after boiling, in the water brought away by us. This is probably due to the presence of some empyreumatic matter.[38] Our guide informed us with a serious face that hell was in the immediate vicinity, and that when Gaudama walked over this spot, the flames burst forth, and endeavoured to devour him, but the springs issued forth and quenched them, becoming heated in the contest. He also told us that a footprint of Gaudama was visible close at hand, in a romantic glen, down which flowed a mountain torrent called the Chalktaw. The stream was crossed by a double-spanned bamboo bridge, supported in the middle of the stream by a large boulder, and hung at either end to two bamboos driven into the ground, so that the bridge is partly arched and partly suspended. Many Kakhyen and Leesaw men and women were coming down the hill on their way to Sanda market, bringing great loads of vegetables, firewood, and planks of wood three feet long, fifteen inches broad, and one inch and a half thick. A basket of vegetables and a plank so heavy that one of us could scarcely lift it formed a mountain-girl’s load down the steep hillside. About a quarter of a mile up the wild glen, strewn with enormous waterworn granite boulders, we were shown the giant footprint in a spot surrounded by some fine old banyan trees. The print was on the end of a boulder looking up the glen, and it was evident that the hollow representing the heel had been formed by the friction of a superincumbent boulder. In time the river changed its course, and the boulder was exposed to the view of some devout and imaginative Buddhist. He, struck with the resemblance of the cavity to a huge heel-mark, carved the outline of a human foot, and proclaimed the wondrous discovery. Its great antiquity is shown by the existence of two tablets on the other face of the rock; the carved outlines are still traceable, but the inscriptions are so worn that it is impossible to decipher the form of the characters. On our way back we passed a Leesaw girl with a great display of beads, and succeeded in coaxing her to part with four strings, and six hoops from her neck, for a rupee. A little further on we met some more of her tribe resting under a tree, who rose and offered us rice-spirit out of their bamboo flasks; in exchange we gave them some watered whisky, which they seemed highly to relish. These Leesaw women wore a peculiar turban with a pendant end, of coarse white cloth patched with blue squares, and trimmed with cowries. Their close-fitting leggings were made of squares of blue and white cloth, and their ornaments consisted of large brass ear-rings, necklaces of large blue beads and seeds, and a profusion of ratan, bamboo, and straw hoops round the loins and neck. These resemble the dress of the Moso women described by Cooper, and similar dresses and ornaments are shown in Mons. Garnier’s illustrations of the Leisus in North Yunnan.

At three o’clock in the morning of August 29th, we were all startled from sleep by a loud outcry and a pistol shot. It turned out that a thief had opened the door and stolen one of the handsome silver Panthay spears, but the jingle of the ornaments had awoke Sladen, who fired a shot in the dark after the retreating robber, and raised an alarm, in vain. Suspicion at once fell on a phoongyee who slept in a room close to the door; the sentinel on duty had heard the priest stirring just before, and while he walked a few yards to consult a watch hung up on a post, the robbery was effected. The tsawbwa and his headmen showed great concern, and all agreed in suspecting the priest, whose character, it appeared, was already bad. They taxed him with the theft, and told him that it was a most disgraceful act, to steal a gift made by one official to another; they also threatened, if the spear was not restored, to degrade him from the priesthood, theft, even to the value of six annas, being one of the crimes which, at his ordination, the rahan is specially warned against, as depriving him ipso facto of his sacred character.

The tsawbwa was extremely incensed, and requested us to delay our journey to enable him, if possible, to discover and restore the spear, as well as punish the criminal. Early the next morning an old woman came crying to the khyoung, and, as she entered, threw down her pipe, and rushed up to Sladen with her hands clasped, and the tears streaming down her wrinkled cheeks. The interpreter explained that she was the mother of the suspected priest, and had come to intercede for him. Another of her sons presently joined her, but they were advised to go to the tsawbwa, in whose hands the matter rested. While she was being shown the door through which the thief had entered, the phoongyee himself came in, and the old woman, with a violent outburst of abuse, struck him several blows with her clenched fist, and fairly beat him out of the khyoung.

The ceremony of excommunication took place in due course, and was brief enough, lasting only five minutes. He was brought in by all the headmen, and attended by his mother and brother, the latter carrying the clothes of an ordinary Shan, which the culprit, when degraded, was to assume. All sat down, and the poor old woman made an affecting appeal to her son to confess if he were guilty; but he preserved a dogged silence, and commenced to take off his turban in front of the altar. She then retired, departing with her hands clasped above her head, and ejaculating prayers. The priest, having removed his turban, took a water lily from an offering of flowers in front of the image of Gaudama, and, placing it on a tripod, again deposited it before the image. The chief priest now appeared on the daïs, and the culprit knelt behind his lily muttering a few sentences, occasionally rising from his knees, and bending in worship before the figure, and gradually retreated after each prostration, until he was beyond the verge of the daïs peculiar to the priests. He then knelt before the chief phoongyee, and repeated some formula after him, after which he retired to his room, and soon emerged dressed as a layman. He was then taken away by the headmen, and some hours after was brought back led by a chain secured to an iron collar round his neck. In the evening he was again led by the chain, down to the khyoung, escorted by the headmen, who stated that they had failed to find any clue to the missing spear, or to establish the guilt of the prisoner. He was, however, during the ensuing conference as to our departure, kept chained to a pillar and guarded by two men. After another day of delay and barter with the people, who crowded the khyoung, the only noticeable purchase being some capital tobacco at the price of a rupee for three pounds and a half, we took our departure on August 4th. The old tsawbwa and his grandchild came with a parting present of cloth, and a request that we would not mount until we had passed his house; and a silver watch presented by Sladen to his adopted son gave immense pleasure to both the chief and his heir. As we approached the haw, three trumpeters blew a lusty blast, and the three saluting guns were fired as we ascended the steps leading to the gateway, where the chief and his grandson awaited us. After a hearty handshaking, and formal adieus, we mounted under a second salute, and rode out of the town preceded by the trumpeters in full bray.

The road at this season was carried along the embankments of the paddy fields nearer to the base of the hills. The courses of the many mountain streams showed the traces of the devastation caused by the unprecedented floods of the past week; whole rice fields had been swept away, and in others the crop had been hopelessly buried in silt. Roots and stems of large trees everywhere blocked the channels, and the sides of the mountains showed red patches, like wounds, where landslips had occurred. These had been most destructive; nine villages were said to have been overwhelmed in the Sanda valley, one, a village of forty houses, being completely destroyed with all its inhabitants, save nine who were absent. The nineteen miles to Manwyne were accomplished by 5 P.M., and we took up our quarters in the same khyoung as on the former visit; some trouble and a little gentle violence being requisite to exclude the pertinacious and curious Chinese, who went so far as to hustle a sentry. These Manwyne people (not including the Shans), though not so hostile as on our first visit, were evidently ill-disposed, and can be only classed as “rowdies.” At sundown a bell was rung and a huge candle lit in front of the altar, while the priests, kneeling on the upper daïs, supported by choristers on the lower one, chanted their vespers.

Bell-ringing and matins woke us up early in the morning, and, as before, the devout women trooped in with their offerings of rice and flowers. The phoongyees and some others were very much interested in hearing about railways, telegraphs, and other wonders of Western civilisation. One of the Sanda headmen remarked that they were much privileged to hear of such things, and that we must all have met before in a previous existence, and would doubtless meet again. They were awed by viewing the moon through a good telescope; and a prediction of the coming eclipse of the sun evidently impressed them with a deep sense of our astrological powers, the chief phoongyee, with bated breath, inquiring whether it presaged war or famine.

Our first visitor was the “Death’s Head” pawmine of Ponsee, who came with the idea that we should entrust ourselves to his friendly guidance, and was chagrined at the information that we should return by Hotha. The Hotha tsawbwa had been delayed by the difficulty of crossing the mud left by the floods, and, when he at length appeared, was at first inclined to magnify the difficulties, physical and otherwise, of reaching his valley. When he found us resolute, he made light of the difficulties, and arranged that the Manhleo poogain should take charge of the baggage, while he himself preceded us to prepare for our reception. In the meantime we were entertained at a dinner by the tsawbwa-gadaw, the honours being done by the Hotha chief. We were welcomed by the two Buddhist nuns, one a daughter of our hostess, and the other a sister of Hotha, attended by a crowd of maids and retainers, and were at once requested to take our seats at the table. Tea was then served, followed by the dinner, consisting of well-cooked fowls, roast and boiled, pork, &c., with small plates of onions, peas, and sliced mangoes; then came rice and sauce, followed by another service of tea. All the dishes were served on Chinese porcelain, and the samshu was poured from a Birmingham teapot into tiny cups of jade. We were waited on by men; but just as the dinner was placed on the table, the hostess came in for a few minutes, and made a speech of welcome, and apologies for having nothing better to offer; and when it was over, she rejoined the party. The two rahanees and their maids favoured us with their company all the time. Being struck with the red-dyed nails of the ladies, I asked one rosy-cheeked damsel to show me the dye. She volunteered to give a practical illustration, and at once brought from an inner room a pulpy mass of the petals and leaves of a red balsam beaten up with cutch. Having first begged for a small ring as a memento of our visit, she proceeded to envelop the tip of my little finger in a portion of the pulp, and covered it with a green leaf neatly tied on with thread.

After dinner the Hotha chief entertained us with a performance on the Shan guitar or banjo, for the instrument had only three strings, and the sounding-board was made of a stretched snake skin. The chief was evidently regarded, and justly, as a skilled performer, and under his fingers the instrument discoursed sweet, pleasant tinkling, while the airs, though simple, were melodious. After our return to the khyoung, the two nuns and their maids arrived with some presents from the tsawbwa-gadaw, and remained for two hours, asking intelligent questions about our country and religion, and on leaving made us promise to visit them at their own khyoung. The next afternoon a messenger came to remind us of our promise, and two of the party went to the nunnery. It consisted of two bamboo houses, side by side, enclosed by a fence. One, used as a residence, was an ordinary Shan house of three rooms; the other, used as a chapel, was a pavilion, twenty-four feet square, raised on piles four feet above the ground, and closed in with mats on all sides save that fronting the dwelling-house. The only decorations were a few small images of Gaudama, and strips of white paper cut into ornamental figures and suspended like banners from the roofs. The Hotha nun was engaged in weaving, which was a breach of the Buddhist canons, forbidding the religious to employ themselves in any useful labour. We were invited into the dwelling-house, and served with mangoes and women’s tobacco, and bidden to light our pipes. A long and interesting conversation ensued, mainly on religious subjects. The nuns, especially the young lady of Manwyne, evinced great interest in the subject of Christianity, concluding by begging us to consider her as a sister. Then we all adjourned to afternoon tea at the haw of her mother. The old lady expressed a great desire to possess a portrait of our gracious Queen, which we promised to send her from Rangoon. In the meantime, we offered a temporary substitute in the shape of four brand new rupees, with which she was greatly pleased.

August 9th found us ready for an early start from Manwyne, but the want of porters delayed us till 8.30, when we set out for the Tapeng. A farewell dish of rice and spirit, “to strengthen us for the journey,” arrived from the tsawbwa-gadaw, while the chief phoongyee presented some cloth to each of us, heartily expressing his good wishes for our welfare. The townspeople waved their adieus, some calling out Kara! kara! and others the Shan equivalent for Au revoir! It was noon before the ponies were safely across the river, now six hundred yards in breadth, on the other side of which a mud flat extended for two miles. The smooth surface had been caked hard by the sun, but with many a fissure, through which the legs of the ponies slipped into the tenacious quagmire beneath. At last a veritable Slough of Despond was reached, and the party was fairly bogged; the ponies floundered and stumbled so much that it became necessary to dismount. The next half-hour will not be easily forgotten, when, the reins in one hand and my dog held fast in the other, I plunged and struggled through the slimy ooze, which seemed to grasp the legs firmly at each step. At one place the pony made a sudden stumble, and disappeared in the mud, whilst the strain sent me rolling forwards until dragged to my feet by two unincumbered natives. The stoutest of our party was literally hauled through by men stimulated by rupees, while his pony had to be dug out of the mud by some Shans. A blunder of our guide had led us into this tract of mud, which had been recently deposited by the overflow of the river; and the amount of alluvium brought down can be imagined from the fact that the tract covered about six square miles, with an average depth of four feet. Following the embankments of the paddy fields for about two miles, we halted for breakfast on a grassy slope at the foot of the hills, under the shade of wide-spreading banyan and mangoe trees, amidst eager crowds of villagers staring at the strangers.