CHAPTER X.

THE HOTHA VALLEY.

The mountain summit—A giant glen—Leesaw village—The wrong road—Priestly inhospitality—Town of Hotha—A friendly chief—The Namboke Kakhyens—The Hotha market—The Shan people—The Koshanpyi—The Tai of Yunnan—Their personal appearance—Costume—Equipment—The Chinese Shans—Silver hair ornaments—Ear-rings—Torques, bracelets, and rings—Textile fabrics—Agriculture—Social customs—Tenure of land—Old Hotha—A Shan-Chinese temple—Shan Buddhism—The fire festival—Eclipse of the sun—Horse worship—Ancient pagodas—Roads from Hotha.

At 2 P.M. we commenced to ascend the hills, which from Manwyne had not appeared to be more than one thousand feet high, but proved to be three times that altitude above the river. The rough bridle-path led straight up the steep declivity, and in the blazing heat of an unclouded sun the ascent was most trying to man and beast, already wearied by their exertions in the quagmire. The mules were ahead, but our men soon began to lag, although we went as slowly as was compatible with the prospect of reaching Manloi, on the other side, before nightfall. A short way up the mountain, bold cliffs stood out, of white crystalline marble, weathering to a dull brown. This was succeeded by quartzose rock; and, still higher, a blueish gneissose rock formed the upper mass of the range. We passed through several Kakhyen villages, paying a few rupees by way of toll to the headmen, who were sitting by the roadside waiting for us. Near the summit, we had a splendid view of the course of the Tapeng to the Burmese plain. A high curtain of clouds to the westward hung over the entrance of the river into the gorge of the hills, while below and beyond it the immense plain of the Irawady was clearly discerned backed by high hills, and with the great river winding through it like a broad silver band. To the right extended a magnificent panorama of the valley as far as the spur above Sanda, and we took a long farewell gaze at the lovely vale, walled in by its guardian mountains, and rich in every variety of effect produced by the grouping in sunset lights and shadows, of flood and fell, and verdant fields. Having crossed the summit more than five thousand feet above the sea, we looked down on the narrow Hotha valley, not a thousand feet below, stretched out at our feet for twenty-five miles, the opposite or southern range trending round to the north-east to join the mountain wall of the Sanda valley, by a connecting ridge, much lower than the height from which we looked across, and saw to the south successive distant heights cradling valleys whose waters flow to the Shuaylee.

It is somewhat difficult to find an appropriate term for this lofty mountain-cradled district. It is a giant glen, scarcely above two miles wide, presenting no level ground, but a succession of broken surface diversified by tossed grassy knolls of red soil, dotted here and there with villages, each with its plantation of fruit trees. A narrow stream, the Namsa, winds down on the southern side, till, through a cluster of higher grassy hills covered with bracken, it forces its downward way to the Tapeng. Such is the valley of Hotha as it lay smiling before us in the fast fading light, with its hundred villages, tenanted by forty thousand peaceful and industrious Chinese-Shans, which compose the two states of Hotha and Latha, or Muangtha and Hansa.

Having commenced to descend the ridge, we met with some Leesaws carrying a freshly killed deer, which an offer of ten rupees failed to induce them to part with. Many tracts of temperate forest trees, such as oaks and beeches, were seen, and below them extensive tracts of a novel short and thin stemmed bamboo. We presently passed through the village of our Leesaw friends, picturesquely perched on the face of a steep spur among magnificent trees and enormous grey boulders, some of which were as large as the houses, which latter differed altogether from the Kakhyen habitations, being small square structures, with no floor save the ground, which was kept dry by means of a trench cut round the mud walls. We entered the village street by a wooden gateway, and passed out under a long covered passage embowered in luxuriant creepers.

The sun had set almost as we commenced the descent, and darkness overtook us halfway down. At a division of the path, a stubborn muleteer insisted on choosing what proved to be the wrong road, and half our party, including the Manhleo headman, were thus misled. We blundered along a rough bridle-track covered with loose stones and cut up by watercourses. In vain we shouted to attract the attention, and learn the whereabouts, of the rest; no answer was returned save the echoes from the hills, now shrouded in darkness. At last we met some Shans, and learned that we were close to a village called Mentone, in the Latha or western division, and some miles from Hotha. A consultation was held as to which alternative was the worst, to proceed in the dark to Hotha, or go dinnerless and supperless to bed. The latter seemed the least evil; so we made for the village khyoung, which was reached at 8.50 P.M. We could get nothing to eat; and, thoroughly tired, we unsaddled the hungry and worn-out ponies, and, taking their saddles for pillows, fell asleep on the floor in front of the altar. Our slumbers, however, were soon disturbed by the phoongyees squatting down close to our heads, and shouting out their evening prayers. The chief phoongyee, a shrivelled old man, sat cross-legged, with his prayer-book on a small stool before him, and a little acolyte sat by his side, running a wooden pointer along the lines to keep the priest’s eyes from wandering. Before him sat six choristers yelling in different keys at the pitch of their voices. The devotions of the phoongyee were interrupted by our Shan interpreter, who shouted to him that he wanted to buy four annas worth of rice. The priest at once stopped the service to bargain as to the quantity of rice to be given for the coin, which was new to him; this being settled, he resumed his office, but was again interrupted, as he had not sent any one to serve out the rice.

Prayers being ended, we requested something to eat, and were told that there were some pears on a tree outside, to which we were at liberty to help ourselves, a generous offer which was politely declined. The priest, however, gave us quilts to lie on; and being thus made at all events warmer, though still hungry, we fell asleep, and, waking before dawn, were well on the way to Hotha by sunrise.

The inhospitality of these phoongyees was in singular contrast to the tenets and practice of the Burmese Buddhist priests, who hold it a pious duty to receive and refresh the stranger. There was, however, an ill feeling at work against us, which found vent in the question asked by some of the villagers, “Why had we come to their valley to bring flying dragons and other evils on them?” This was due to the malicious reports that the Muangla people had spread. The unexampled inundations were attributed to our presence, and it was declared that our stay had been followed by death in each place. Even the Hotha chief was not free from the superstitious dread thus produced; and his father-in-law, the old Latha tsawbwa, though he accepted the presents sent him, utterly declined a visit, as he feared the strangers would bewitch him and his household. His dutiful son-in-law declined to press him, as he was “an old buffalo,” which always went in the contrary direction to that in which it was driven.

Turning our backs on the inhospitable village, we proceeded by an excellent paved road carried along the end of the spurs, and in many places cut out along the slopes. The mountain streams were crossed by means of granite bridges, some of them adorned with dragons. Numerous villages embowered among fine trees were passed; and a novel feature was introduced by the occurrence, at intervals, of roadside drinking-fountains, the wells being built over and cased in stone ornamented with a white marble frieze. A gilded pagoda surmounting a hillock opposite Manloi brought our thoughts back to Burma, as it was the first pagoda of the Burmese type seen since our departure from the plains.

At 8 A.M., August 10th, we arrived at the town of Hotha, consisting of about one hundred and fifty houses, surrounded by a low wall, somewhat ruined and dilapidated, the result, not of Panthay invasion, but of a rebellion by the tsawbwa’s subjects, who a year before, exasperated by the imposition of a new tax, rose and attacked his town. The tsawbwa and his son, in state dresses, the former attired as a mandarin of the blue button, received us at their residence, and a salute was fired from four mortar-shaped guns embedded in the ground. Quarters were assigned to us in the haw, close to the chief’s private apartments; and all our people were assembled in the course of the day. The whole of the baggage was brought in safely, although the party had been divided in the descent of the mountain, and some of the followers had been obliged to remain in the Leesaw village, the unsophisticated mountaineers charging them two rupees a head for their night’s lodging! The Manhleo poogain and Kingain, the Muangla headman to whom the convoy of the baggage had been entrusted, were very proud of the encomiums passed on their successful performance of their task, and requested a certificate to that effect, and further promised to assist all future travellers who might desire to cross from Manwyne to Hotha.

We remained until the 27th as guests of the courteous and accomplished chief Li-lot-fa, or, to give him his Chinese appellation, Li-yin-khyeen; and the recollection of our sojourn with him, and of his pleasant valley, is the most agreeable of all the reminiscences of the country beyond the Kakhyen hills. Not only did our host evince the most hospitable desire to purvey all creature comforts, but he made us feel thoroughly at home. We lived on terms of intimacy with his family, and his two wives and two daughters manifested a charming freedom of manners, combined with the most refined propriety, that would have done credit to a drawing-room at home. The chief delighted to converse about the various modern inventions of which he had heard reports from the Chinese who had visited Rangoon. Their accounts, however, more suo, had been full of marvellous exaggerations, including flying-machines, telescopes that enabled the sight to penetrate mountains, and others that divested people of their clothes! The chief had some vague ideas about railways, steamships, and gas, and was most eager for fuller and more accurate information.

We urged him to visit Rangoon and Calcutta, but he seemed to think the disturbed state of the country an insuperable obstacle; but he discussed, instead, the plan of sending his son, a lad of thirteen, to Rangoon. Li-lot-fa could read and write Shan and Chinese, and he now commenced to learn Burmese, and it was a curious sight to see him at work with his note-book, which he had obtained from us, taking down words and sentences as busily as if he had been a competition wallah preparing for an examination.

The fact that this tsawbwa had succeeded in maintaining friendly relations with both the Panthays and imperialist Chinese chiefs, with whom his real sympathies lay, so that his valley had escaped the evils of war, spoke well for his diplomatic tact. His conversation showed that he had been from the first well informed about our progress and difficulties, which he unhesitatingly attributed to the machinations of the Bhamô Chinese. He asserted that the advance to Ponsee, and the desertion of the muleteers at that place, had been part of a well concerted scheme on the part of the Kakhyen chiefs to attack and plunder our baggage. Our escape from this danger was attributed by the chief to “a supernatural power against evil, given as a reward for good deeds in former existences.”

As an energetic trader, he was most anxious to co-operate heartily in reopening all the trade routes, his especial object, as was natural, being the restoration of the central or embassy route, which had been closed for some years by feuds between the Kakhyens of the hills on the southern side of the Tapeng and the Burmese officials. The cause of quarrel was stated to have been an unprovoked attack, on the part of the Burmese, on a few Kakhyens.

The tsawbwa possessed great influence over the Kakhyen chiefs through whose territory this route passes, an instance of which was speedily given by the arrival of the chief of Namboke, accompanied by his pawmines, and a strong armed guard, the chief and his officers being mounted on ponies. As soon as he saw Sladen, he went down on one knee, in the most respectful manner of greeting, and recalled himself to his recollection as having visited us at Bhamô and received a present of a head-dress. This chief scarcely resembled a Kakhyen, his naturally Tartar-like cast of countenance being heightened by his Chinese skull-cap and dress. After remaining one night and expatiating on the advantages of the embassy route, he set out for home, bearing a letter from Li-lot-fa to all the Kakhyen chiefs, which the pawmines were to carry forward, inviting them to come in and arrange for our safe progress to Bhamô.

The bazaar or market, which is held every fifth day, took place on the 12th. There are no shops or shopkeepers, except where the Chinese reside, among the Shans, and all sale or barter is necessarily conducted at these regular markets or fairs, which are thronged by the people of the valley and adjacent hills. The Hotha fair was held on a grassy slope, about half a mile distant from the town. There were no permanent or temporary stalls, the vendors simply sitting down in long lines with their goods before them. One section was devoted to the sale of sword blades, the manufacture of which is a speciality of this valley, and another to the wooden scabbards and handles. After buying two fine blades for four shillings each, I was assured that the vendor had charged one-third over the value.

Another quarter was devoted to the sale of samshu, and close by it were the restaurants, where the hungry customers refreshed themselves with hot pork, vermicelli, or an article exactly like it, various vegetables, and peas, all hot and nicely served in little white bowls. The butchers’ quarter was amply supplied with pork and beef, and fowls and ducks were plentiful. Long lines of Kakhyen women from the hills offered for sale joss-sticks, pears, apples, plums, peaches, mustard leaves, and a variety of hill vegetables, along with basketfuls of nettles, as food for the swine, which are an invariable adjunct of a Shan household.

In the centre of the market, on a double row of stalls, were displayed various kinds of Shan cloth, Shan caps, Chinese paper, rice cutch, flint, and lime, which are brought from Tali-fu, white arsenic, yellow orpiment, &c. In another quarter, English green and blue broadcloth was selling at twenty shillings per yard, along with red flannel, for which the Kakhyens have an especial affection. It seemed to us, however, that, although the price was high, a very few pieces would “glut the market.”

Indigo, the universal dye of the dark blue-clad Shans, Kakhyens, and Chinese of Western Yunnan, also had its own quarter. The fair was thronged with people, the elder busy chaffering over their few wares, and the younger strolling about and gossiping. Almost all were clean and well-dressed, and there was an absence of the poverty-stricken class, which had been so numerous in the various towns of the Sanda valley, all appearing to be well-to-do, to judge from their appearance. The women, as a rule, were little and rather squat, with round, flat, high-cheek-boned faces, and slightly oblique eyes. Some of the younger women, with fair skins and rosy cheeks, might have been accounted good-looking, but were disfigured by the strange custom of dyeing the teeth black, which is the fashion among Shans of the better class. The dye is probably a preparation of cutch, and, according to the tsawbwa, the custom originated in a desire to preserve the teeth from decay.

For the first time we noticed the peculiar and picturesque dress of the Chinese Shan women. The men, with the exception of an occasional red turban, were dressed in the universal dark blue. The costume of the Hotha Shan women only differed from that remarked in the Sanda valley in the prevalence of dark green jackets and the number of large silver hoops worn round the neck.

It will be well here to summarise, even at the risk of repetition, our observations on the Shan inhabitants of these valleys, who belong to the Tayshan or Great Shans of the Tai race, the branches of which, under different names, are found extending to the eleventh parallel, their various states being tributary to Siam, Burma, or China. The Shan population where it has been absorbed into the Burmese kingdom has become assimilated in language and customs with the dominant race, from which they can scarcely be distinguished. Throughout the valley of the upper Irawady above Bhamô, but with the Kakhyen hills interposing their stratum of hill tribes between them and their brethren of the Chinese states, the Shan element predominates, though contending with the wilder Singphos to the west of the valley. The inhabitants, though speaking Burmese, still preserve the Shan language, and retain the physical and other characteristics of their race.

The little states of Manwyne and Sanda, Muangla, Muangtee, Muangtha, or Hotha and Latha, and Muangwan and Muangmow, which lie on the right bank of the Shuaylee, are the remains of the Koshanpyi or Nine Shan States, forming the chief component parts of the Shan kingdom of Pong, conquered by the Chinese in the fourteenth century. Bhamô or Tsing-gai, with the country extending to Katha, or perhaps to Tsampenago, and the upper part of the valley of the Irawady, with Mogoung as its chief town, were the last remaining independent remnants of this state, and have been included in Burma since the annexation by Alompra in 1752 of the semi-independent state of Mogoung.

It seems most probable that the walled Chinese town of Muanglon represents Muang Maorong, the ancient capital of the Pong kingdom, and the Chinese Shan states of Sehfan and Muangkwan, and possibly the state of Kaingmah, which is reckoned among the Koshanpyi, are under the jurisdiction of its Chinese governor, as the states we visited are dependent on Momien. Throughout Yunnan, and, according to Garnier, as far as the confines of Tong-king, the Tai race is widely diffused. The names of towns and districts seem to indicate that this region of lofty hills and great valleys was formerly the seat of the Shan kingdom, and still—though intermixed with the wild hill tribes, and the descendants of the Chinese colonists, who were settled in the newly acquired conquests—the Shans, under the name of Pa-y, hold their ancient ground. Mons. Garnier mentions that at Muang-Pong he found villages peopled with Tai-ya settlers, who had fled from the Mahommedan ravages, and settled beyond the borders of Yunnan. His description of their characteristic dress and silver ornaments would almost exactly apply to the Chinese-Shans of the Hotha valley. He describes some Tai-neua[39] refugees met with at Kiang-hung or Xien-hong itself, and remarks on the resemblance between these two divisions of the Shans. As soon as he had passed into the country where the Laotian language ceased to be understood, on the confines of Yunnan, near Se-mao, “The inhabitants presented an intermediary type between the Chinese and the Tai race. This mixed type faithfully represents that of the ancient population of Yunnan, or that of the Tai, who were conquered by the Chinese.” And at Yuen-kiang he remarks: “The Tai, whom the Chinese call Pa-y, are the ancient inhabitants of the country of Muong-Choung, which is now called Yuen-kiang. They are more numerous and more independent as the frontier of Tong-king is approached.” Thus the Chinese province of Yunnan on the one side and the upper portion of the valley of the Irawady on the other contain a largely preponderating element of Shan population, their national characteristics, however, gradually becoming obliterated by the influence of the ruling races respectively. Owing to their local position, which has preserved their subordinate independence, the little nest of valleys, cradled in the parallel secondary ranges which lie between the Salween and the Irawady, has preserved, almost unmixed, the relics of the ancient Shan kingdom, and it is with their inhabitants, so far as our observations extended, that we have to do. It is with some uncertainty that the terms Shans proper and Chinese Shans are used; not so much as indicating a theory of race as to serve as a practical distinction between the two divisions, which, though claiming to be one in race as in language, will be seen to present curious differences; while the Chinese-Shans, or Sino-Shans, as some have called them, may, according to the evidence of the French explorers, really represent the original Tai race more directly than the Shans of the Tapeng valley and the Irawady valley.

The Shans proper of these valleys are a fair race, somewhat sallow like the Chinese, but of a very faintly darker hue than Europeans, the peasantry, as a rule, being much browned by exposure; they have red cheeks, dark brown eyes, and black hair. In young people and children, the waxen appearance of the Chinese is slightly observable. The Shan face is usually short, broad, and flat, with prominent malars, a faint obliquity and contraction of the outer angle of the eye, which is much more marked in the true Chinese. The nose is well formed, the bridge being prominent, almost aquiline, without that breadth and depression characteristic of the Burman feature. The lower jaw is broad and well developed; but pointed chins below heavy, protruding lips are not infrequent. Oval faces laterally compressed, with retreating foreheads, high cheek-bones, and sharp retreating chins, are not infrequent; and the majority of the higher classes seemed to be distinguished from the common people by more elongated oval faces and a decidedly Tartar type of countenance. The features of the women are proportionately broader and rounder than those of the men, but they are more finely chiselled, and wear a good-natured expression, while their large brown eyes are very scantily adorned with eyebrows and eyelashes. They become much wrinkled by age, and, judging from the numbers of old people, appear to be a long-lived race. They are by no means a tall people, the average height for men scarcely reaching five feet eight, while the women are shorter and more squat in figure. The only difference between the Shans and Poloungs, so far as my limited observation went, seems to be that the latter are darker and smaller; but the Chinese Shans, or Sino-Shans, of the Muangtha valley differ widely from their congeners. They are a much smaller race, their little, squat figures and broad, short flat faces reminding one of Laplanders. The cheek-bones are very prominent, and their faces are much flatter and shorter than those of the other Shans. The breadth between the eyes, which are markedly oblique, is considerable, and the mouths are heavy, with protruding lips. In the women these characters are more pronounced, and their complexion strongly resembles that of the Chinese.

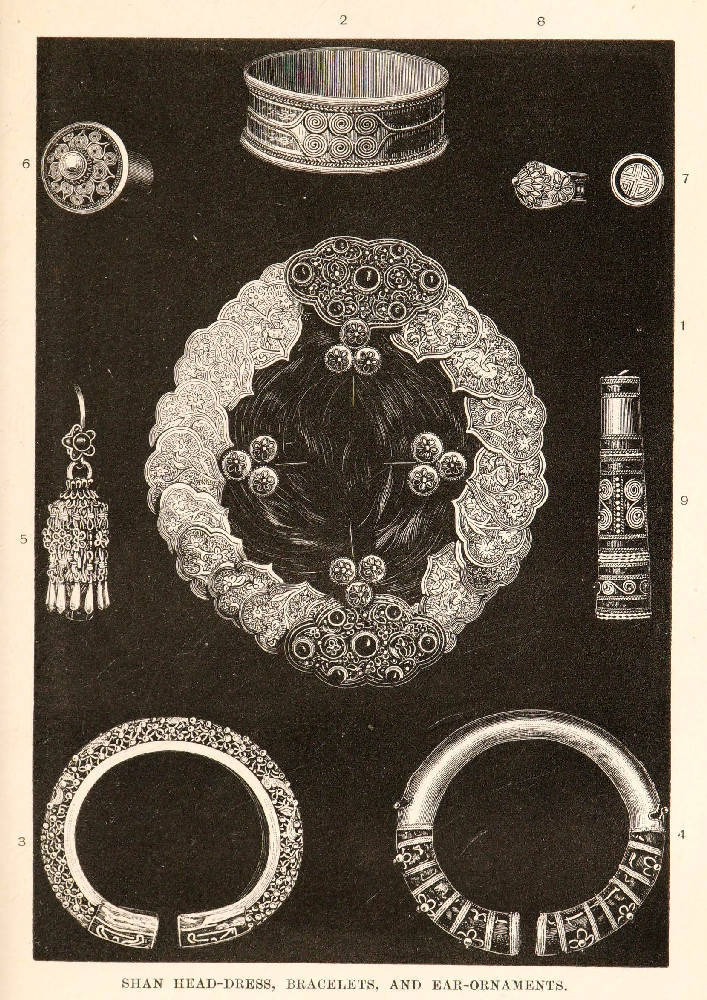

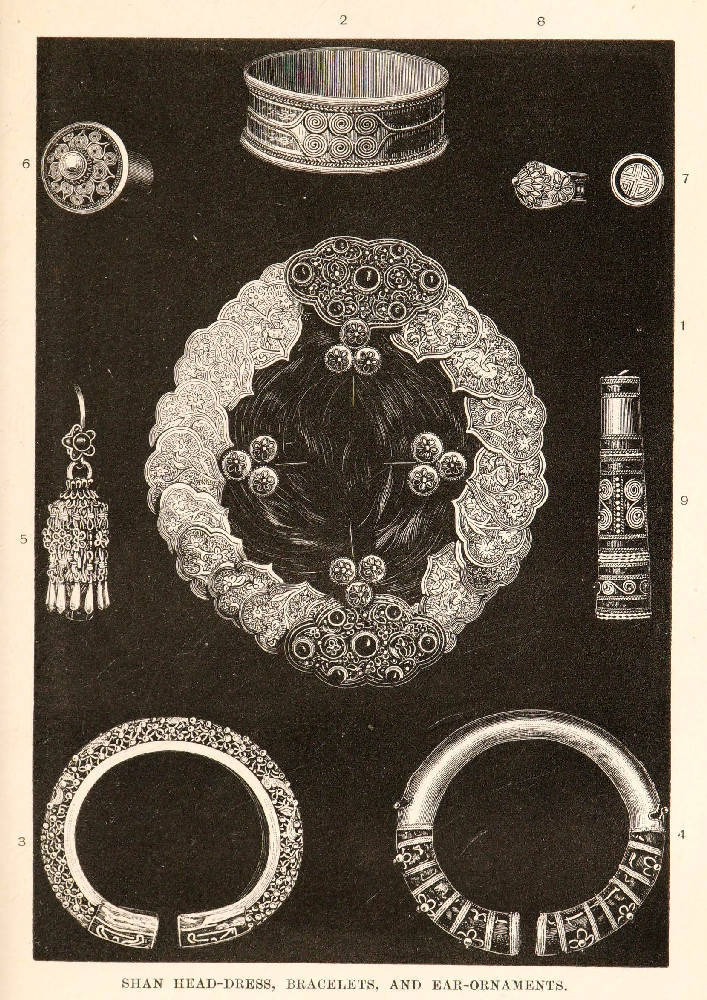

In the ordinary attire the Shans, except the Chinese Shans, are almost uniformly dressed in sombre dark blue, the dye being obtained from the wild indigo. In full dress, however, the women display an appreciation of colour which would delight an artist. The peculiar head-dress, like an inverted cone, has been already alluded to. It consists of a series of long blue scarves, a foot broad, and of a total length of forty to fifty feet, wound round and round the head in a huge turban, towering upwards with a backward slope, like that of the Parsee head-dress. The folds are arranged in a crescent over the forehead with most exact precision; the free end, embroidered in gold and silk, and sometimes adorned with silver pendants, hangs gracefully down the neck. The hair, left uncovered in the hollow of this structure, is adorned with silver hairpins, the heads of which are richly enamelled to represent flowers and insects. The jacket, of blue or green, and sometimes pink, is short and loose, with a narrow and erect collar. Thin square plaques of enamelled silver fasten it at and below the neck, to which are sometimes superadded three rows of large round silver bosses, enriched with birds and flowers enamelled in various colours. The loose sleeves are folded back from the elbow, displaying massive silver or silver-gilt bracelets. A tight thick skirt of cotton cloth, deeply bordered with squares of embroidered silk or satin, close-fitting leggings, and embroidered shoes, complete the toilette, a richly variegated cloth being sometimes worn as a girdle. A Shan lady thus attired is incomplete without a silver flask-shaped scent-bottle about three inches across, adorned with silver studs and pendants terminating in round silver bells, which jingle as the wearer moves. Silver chatelaines are also worn, and a needlecase formed of a silver tube, enamelled and studded, enclosing a cushion, which is attached to the waist. Silver neck-hoops, ear-rings, and rings, which deserve particular description, complete the adornments of the Shan belle, who, moreover, is seldom seen without her long-stemmed pipe, with its small bowl of glazed clay.

The male peasants wear a long double-breasted jacket of blue cotton, buttoned down the right side, often with jade, amber, or silver buttons. Of the same material are their short wide trousers and thick turbans, with a long fringe at the free end, which is usually coiled up with the pigtail on the outside. Long strips of blue cloth wound round the shins serve as leggings, and their shoes are made of cloth resembling felt, embroidered with narrow braid and soled with leather. A very broad straw hat covered with oiled silk serves as an umbrella against rain or a scorching sun.

The better classes, such as the headmen of the towns, wear long blue Chinese coats reaching to the ankles, and black satin skull caps ornamented with Chinese figures worked in gold braid. The little boys don blue cotton caps, braided, with a red topknot, and garnished with a row of silver figures of guardian nats. A silver chatelaine, with a number of little instruments, such as tweezers to depilate the face, ear and tooth picks, is frequently worn by the men. It hangs from the button-hole by a long silver chain, ornamented with beads of jade, amber, or glass, or with grotesque figures of animals carved in jade or amber. Two essentials in a Shan’s equipment are his dah and tobacco-pipe. The dah has a blade two feet and a half to three feet in length, expanding from the hilt to the almost square point, which is nearly three inches broad. The wooden handle is bound with cord covered with silver foil, and ornamented with a tassel of goat hair. The wooden half-scabbard is attached to a ratan hoop worn over the right shoulder. These dahs are chiefly manufactured by the Muangtha Shans from iron imported from Yunnan. They use charcoal as a fuel, and a bellows made of the segment of a large bamboo, with a piston and valve at each end. They supply all the hill tribes with weapons, and, as before remarked, resort to Bhamô and elsewhere to work during the winter months. These weapons exactly resemble those made by the Khampti Shans, and, like them, are keen and well tempered. The tobacco-pipes are remarkable on account of their elaborate silver stems, which are frequently a yard in length, and enriched with enamelled flowers and silver twist. Sometimes the stem swells at intervals into elongated silver spheres. A long bamboo stem intervenes between the silver and the bowl of glazed earthenware. The wealthier Shans frequently use the Chinese hookah, and the poorer the Chinese brass or iron pipes with small bowls. Tobacco, home-grown and of very excellent quality, is carried in small round boxes made of buffalo hide covered with red varnish. They are made in two halves, the upper overlapping the under, the hide being moistened and stretched over a wooden mould.

The costume of the Chinese Shan women of Hotha and Latha differs in a marked manner from that already described. They wear the Shan jacket and loose trousers like the men, and usually are barefooted. The back part of the jacket is prolonged to the knees in a half skirt, and a double Chinese apron in front overlaps it, so as to complete the dress. Besides the large silver plaques, epaulets are worn, of small semi-spherical discs, connected by a line of silver buttons from shoulder to shoulder. The broad waistband of the apron expands behind into a richly embroidered piece, which is a peculiar characteristic of this people. A still more distinctive mark is the head-dress, from which the high turban is absent. The hair is divided and gathered up on the crown of the head, when it is plaited into the ends of a flat chignon encircled by a ratan hoop covered with red cloth. This is kept in position by means of twenty-five to thirty silver pins headed with thin plates of silver embossed or engraved with leaves and flowers, and so disposed as to form a silver coronal. Outside this is wound a slight blue turban, to the pendant fringes of which are suspended a number of silver rings. In full dress four much larger hairpins, with elaborate heads eight inches in length and three inches across, are worn. They are overlaid with silver wire cunningly wrought to represent the stems and leaves of plants, which are enamelled green, brown, and yellow, and enriched with flowers in the same material, the petals formed of red and blue stones, and little silver spheres representing the unopened buds. Sometimes yet another inner circle of smaller pins, each headed with a cluster of four small caps, is added; and an elaborate head-dress forms a circle or an aureole of silver flowers fully a foot in diameter. The various patterns of hairpins are of the most intricate construction. The simplest are made chiefly of silver wire and flat pieces of silver cut into fantastic figures or forms of trailing plants in full flower, the colours being enamelled in green, blue, purple, and yellow. Some are wrought in the finest filigree, one beautiful specimen representing a swan-like bird resting on its outstretched wings among a bed of flowers. The feathers of the wings are most effectively wrought in silver wire, and among the leaflets stand up little coils of silver wire, each terminating in two square cusped discs of silver. These strongly resemble the capsuled stems of mosses; and the general appearance of these pin-heads suggests that the artist has derived his inspiration from the study of a grassy sward covered with flowers and moss; indeed, the most fashionable form of this ornament consists of two tiers of leaf-work, the uppermost supported on fine wire, while through its interstices the capsuled stems rise from the lower tier, as flowers rise above the grass.

This distinctive head-dress of the Chinese Shans seems to characterise the Pa-y or Tai women in the south of Yunnan. M. Garnier describes those of Yuen-hiang as wearing long silver hairpins, from the ends of which hung a profusion of pendants. Their costume consists of a showy corset with a little jacket over it, a petticoat with a broad coloured border, and apron; and he particularly describes a high collar made of red and black stuff, on which little silver studs are arranged in patterns reminding him of the armed collar of a “bouledogue.” The front of the vest is also thickly studded with similar ornaments. The Pa-y ear-rings are of very delicate workmanship, the usual pattern being a large ring supporting a small square plate with numerous pendants, much resembling those of the Chinese Shans. The married women of the latter especially invariably wear a silver or silver-gilt ring, overlaid with studs or filigree work, to which is attached a jade or enamelled silver disc. The Chinese Shan girls wear a tube of silver, from which is suspended an inverted rosette set with a circle of club-shaped pendants. From the centre of this flower-like ornament hangs a filigree ball and rosette set with a garnet. The ear ornaments of the Shans proper are of two kinds, only one of which, worn by the young girls, can be called an ear-ring—the large circle of silver wire suspending a flat spiral ornament resembling a favourite pattern of the Roman period in Europe. There are three forms of the second or of the cylindrical type, necessitating a large opening in the lobe of the ear, but by no means so large as the ear ornaments of the Burmese beauties, which are sometimes an inch and a half in diameter. The first are made of a piece of bamboo, which is covered with silverfoil, one end being finished by a piece of cloth, which is effectively embroidered with the green wing-cases of a beetle, red seeds, and Chinese devices in gold thread. The second form is a short cylinder of silver, with a cross piece engraved with Chinese figures. The third is nearly two inches long, widening into a disc fully an inch in diameter, and terminating in a silver knob. The front is composed of open silver filigree.

SHAN HEAD-DRESS, BRACELETS, AND EAR ORNAMENTS.

Fig. 1. Chinese Shan chignon encircled with silver hairpins.

2. Shan silver bracelet.

3. ” ” ” in filigree.

4. ” ” ” enamelled.

5. Chinese Shan girl’s ear-drop.

6. 7. Shan woman’s tubular ear ornaments.

8. Shan finger ring.

9. Silver tube for enclosing a needle cushion.

These silver ornaments will be seen to be thoroughly characteristic of the Shans, who, it need not be said, are expert silversmiths, their simple tools consisting of small cylindrical bellows, a crucible, punch, graver, hammer, and little anvil. In the Sanda valley the phoongyees are the chief artificers; but in Hotha the trade is still confined to the laymen. Their enamels, of which we could not discover the materials, are very brilliant, and employed with beautiful effect in the floral patterns, which form the principal stock of designs. The only other forms of ornamentation, the rope-shaped fillets and rounded studs or bosses, singularly resemble those found on the diadems and armlets of the early historical periods of Scandinavian art. The plain torques or neck rings in use, especially among the Hotha Shans, only differ from the ancient Irish type by their more rounded form, and by the pointed ends being bent outwards, in lieu of being expanded into cymbal-shaped faces. Another kind of torque is of the same shape, but covered with leaf ornaments and cones in filigree and enamel alternating with red and blue stones or pieces of glass. Torque-like hollow rings, covered with floral enrichments, are worn as bracelets; sometimes they are gilt with very red gold and enamelled, a jewel being usually set in the centre. Another form is a silver hoop, nearly two inches in breadth, with rounded edges and filigree borders, most elaborately set with floral rosettes of three circles, rows of leaves, brown, green, and dark purple, centred by a large silver stud.

The finger-rings are generally made of rope wire, either with conical or flat spiral coils; but one curious type is formed of an oblong ornamented silver plate an inch long, and as broad as the finger. A half-circle from either side enables it to be worn on a finger of any size. Many of the rings are jewelled with garnets, moonstones, and pieces of dark green jade, but no valuable gems were observed. The men commonly wear ordinary Chinese rings of jade or amber.

The women are constantly engaged in weaving and dyeing, for the yarn from home-grown cotton is spun, dyed, and woven by their industrious fingers. They are adepts at needlework and silken embroidery; and all the clothes worn are made and ornamented by the women of each household. Straw-plaiting is another of their industries, and the broad-brimmed straw hats made in the valley would compete with the finest Leghorn fabrics. Another art in which they excel, apparently borrowed from the Chinese, is the manufacture of elaborate ornaments for the hair from the sapphire blue feathers of the roller bird (Coracias affinis). These are fastened on paper cut to imitate wreaths and flowers; and with copper wire, gold thread, and feathers, laid on with the greatest nicety, very pretty simple ornaments are produced, which are often brightened by the addition of a ruby or some other gem.

The stuffs woven in a loom similar to that in use by the Kakhyens are of all degrees of texture, the finer kinds, used for jackets, being very soft, and usually figured with large lozenge-shaped patterns of the same colour. A marked feature of the textile fabrics and embroideries of the Shans, and indeed of their ornamentation generally, is the reproduction of conventional patterns, handed down from their forefathers without any attempt to improve or vary them. The Shan designs of the nineteenth century probably are identical with those of the fourteenth, and are simple modifications of the lozenge, square, and stripe; these modifications may be, and are, almost endless, and the combinations of the elementary forms most intricate, while the ground of the fabrics in which the patterns are wrought is usually covered with numerous small truncated almond-rounded lozenges, interspersed with figures of the sacred Henza, or Brahminical goose. The chief beauty of their textile fabrics consists in the wonderful grouping and harmony of the colouring; and in the employment of their vivid full and half tints of blue, orange, green, and red, they are all but unrivalled artists.

The great body of the Shan population is engaged in agriculture; and as cultivators they may take rank even with the Belgians. Every inch of ground is utilised; the principal crops being rice, which is grown in small square fields, shut in by low embankments, with passages and floodgates for irrigation. During the dry weather, the nearest stream has its water led off, and conducted in innumerable channels, so that each block, or little square, can be irrigated at will. In the valley of the Tapeng, advantage is taken of the slope of the ground to lead canals to fields several miles away from the point of divergence. At our arrival in the beginning of May, the valley from one end to the other appeared to be an immense watery tract of rice plantations glistening in the sunshine, while the bed of the river was left half dry by the subtraction of the water. Tobacco, cotton, and opium are grown on the well-drained slopes of the hills, the two former for home use; but the white-flowered poppy is cultivated to supply the requirements of Chinese, Kakhyens, and Leesaws. A considerable quantity of Shan opium finds its way to Bhamô, and thence to Mandalay, and also to Mogoung, whence it is distributed among the Singphos.

The land is tilled by a wooden plough with an iron share, drawn by a single buffalo. Men and women work together, but the heavy tillage is done by the former, the weaker sex being only employed in weeding and thinning. Vegetables are grown round every house, and form an important article of diet. Numbers of fine cattle and pigs are reared and killed for eating, their flesh, with all kinds of poultry, being largely used, and sold freely in the markets, for the Shans have no Buddhist prejudices. The milk, however, is not used. The entrails of animals, as among the Burmese, are much used in Shan cuisine; a very fair soup, made of the intestines of fowls, being a favourite dish of the Hotha tsawbwa, who insisted, when dining with us, on substituting it for our soup, which he did not approve. The large larvæ of a giant wasp, and stewed centipedes, are Shan dainties which we could not appreciate.

Their principal stimulant is samshu, or rice-spirit; but during our stay amongst them, we observed scarcely an instance of intoxication. The vice of drunkenness and the licentiousness common amongst all their neighbours seem almost unknown among this industrious self-supporting race. They are social and good-humoured, but by no means as jovial as the Burmese, compared with whom they are a quiet, rather sedate people.

As a rule, each man is content with one wife, but polygamy is allowable to those who are wealthy enough; thus the Hotha chief had several wives at various villages. All that is required to contribute a valid union is the sanction of the parents, mutual consent, and interchange of presents between the contracting parties, but no religious rite whatever is observed on the occasion of the wedding.

They are a musical race, and possess many simple wild airs, which they play on stringed and wind instruments. Of the former, which are played like a guitar, one is about three feet in length, with three strings and a broad sounding-board; another is only half the size, the sounding-board being a short drum-like cylinder, with a snake skin stretched across it. This instrument was also a great favourite with the Momien people, and is probably of Chinese origin. The most usual wind instrument is a sort of flute, made of bamboo, with a flask-shaped gourd as mouthpiece, and the sound is full, soft, and pleasing. The long brazen trumpets, which are a sort of state appendage of the tsawbwa, are only blown to announce his arrival, or to do honour to his guests.

The chiefs, although paying an annual tribute to the authorities at Momien, exercise full patriarchal authority in their states; assisted by a council of headmen, they adjudicate all cases, civil and criminal. The tsawbwa is the nominal owner of all land, but each family holds a certain extent, which they cultivate, paying a tithe of the produce to the chief. These settlements are seldom disturbed, and the land passes in succession, the youngest son inheriting, while the elder brothers, if the farm is too small, look out for another plot, or turn traders; hence the Shans are willing to emigrate and settle on fertile lands, as in British Burma. The chiefs naturally do not approve of this, and it is to be feared that the recent emigration of these Shans to our provinces has in the last few years excited the ill-will of the tsawbwas against the British officials, whom they accuse of inducing their people to desert them. In ordinary times of peace and prosperity, the inhabitants of these valleys must have been very thriving, and the chiefs very wealthy, tokens of which appeared in their haws, though most of them had been much injured before our visit; but at this time they were certainly impoverished, and, without doubt, many of the valuable articles of dress and jewellery offered to us for sale belonged to the chiefs and their families. The great anxiety of the peaceable Shans was for the restoration of order, and though they all earnestly longed for the re-establishment of the imperial Chinese régime, they were, in the meantime, most ready to befriend those whose mission was to establish a route for commerce, necessitating peace and order as the conditions of its maintenance.

We found it impossible to obtain a guide to the southern side of the valley of Hotha beyond the Namsa, which is a very small mountain stream. The tsawbwa declared that the bridge had been washed away, and that the road was deep in mud; but he himself planned an excursion for us to visit another house belonging to him at Tsaycow, some miles to the east of Hotha. The chief set off early in the morning to prepare for our reception, and we followed at midday. The road, paved with boulders, and near the villages with long dressed slabs of granite, wound over the grassy spurs, the slopes of which were cultivated with tobacco and cotton. The mountain streams, running over rocky channels encumbered by large boulders particoloured with green moss and lichens, were spanned by bridges of gneiss or granite, those over the larger streams being handsome arched structures, twenty to twenty-five feet in span, with a rest-house at either end, and the parapets often guarded by stone dragons. Each village was approached by a long narrow lane arched by trees and feathery bamboos, terminating in a picturesque gateway, and bordered by stone drinking fountains. The houses were embowered in trees, pear, apple, chestnut, peach, and sweet lime, forming orchards round the villages, and the triple roofs of substantial khyoungs and occasional pagodas crowning the knolls, completed the rural picture, with a background of green slopes of grazing land running up to the rearward wall of mist-clad mountains. One small pagoda, called Comootonay, differed altogether from the ordinary Burmese type, in its peculiar shape and attenuated long spire, which rose to a height of fifty feet. Five miles of pleasant riding past a succession of thriving and picturesque villages, orchards, and khyoungs, brought us to Tsaycow, or Old Hotha, a much larger place than the present town of that name, embowered in trees, and delightfully situated on a spur at the opening of a little dale, down which flowed a fine mountain stream. The chief’s house, formerly his head-quarters, which was built in the Chinese fashion, though smaller than our residence, had the advantage of a better site and superior condition, the private apartments especially being richly decorated with elaborate carvings. In the inner reception hall we were welcomed by the tsawbwa, and, after being refreshed with tea, were conducted by him to see two khyoungs, one Shan and the other Chinese, built, after his own designs, one above the other, on the hillside behind the village. The Chinese temple, which occupied the highest site, was enclosed by a high wall, with a gate leading into a courtyard bordered by cloisters on either side, while a raised pavilion occupied the end, opposite to which, and above all the other buildings, towered the shrine, crowning the highest of two terraces faced with granite. Covered staircases led from the cloisters to the higher level, each terminating in a little rounded tower containing a large bell. The temple occupied the whole of the terrace, with verandahs, paved with stone, to the front and rear. A little stream bubbled up into a small basin in the front, and then formed a cascade from terrace to terrace into the court below. Two entrances led from the verandah into the temple, between which a large window exactly faced the altar-piece. On a table in front of the window stood vases with incense and flowers, and a number of boxes containing the library. The altar-piece, an admirable example of open woodcarving, about twenty feet high, resembled a huge triptych, containing three recesses about ten feet from the ground. It was enclosed by a simple wooden railing four feet high, and before it stood a small table, whereon incense is burned, and at either end two others, with a wooden fish and drumstick on each. The three recesses contained life-sized figures, each with a gauze curtain in front. A beam projecting to the front wall from either side supported two life-sized figures, and along each side wall eighteen small figures were ranged on a platform, with a vase and joss-sticks before each. The tsawbwa acted as cicerone, and explained that the central figure was Chowlaing-lon, the king of all nats, who had existed before Gaudama. The figures on either side are called Coonsang, and act as his pawmines or agents, to execute his orders; and the four standing figures are the rulers of the four great islands or quarters of the globe, who keep a record of all the actions of their subjects. After death each man is brought before Chowlaing-lon, and by him consigned to the Coonsang, who, according to the report given by the rulers, make them over to one or other of the thirty-six nats representing the army of the Thagyameng, ranged in order along the sides. One of these nats was represented with six arms, armed respectively with a belt, bow, arrow, club, and dagger, while one hand was empty as though ready to seize a victim. All the others were in different attitudes, each holding some kind of weapon, and having a long scarf-like band round his neck and shoulders, reaching to the ground, to serve as wings, recalling to our minds the flying people visited by Peter Wilkins.

The lower or Shan khyoung consisted of two oblong buildings on different levels. A grim-looking nat or Beloo guarded the door leading into the temple, where sat three colossal Buddhas, the Past, Present, and Future. On either side were two guardian figures, one mounted on a pigmy elephant, and the other on a mongrel monster, half lion and half tiger. At the feet of the Buddhas was a well executed figure of a tortoise; while vases of incense and sweet-smelling flowers placed on a table sent up their sweet odours to the calm impassive faces above them. At each side of the building, sat a row of life-sized figures, cleverly executed, and one especially, representing a shrivelled old man, with his chin resting on his knees, and the flesh tints admirably given, displayed real artistic power. In the lower temple, which was open in front, the middle of the central wall was occupied by a figure of Kwan-yin holding the child, and surrounded by a number of small adoring figures sculptured in relief; above her head a parrot, holding a rosary in its bill, was perched on a twig. On the other side of the wall, so as to be back to back with the Chinese goddess, sat a colossal Buddha flanked by two gigantic figures, one of which held a rat. The tsawbwa declared that all these temples had been erected in honour of Buddha; and he narrated the history of Kwan-yin, who was the daughter of an ancient emperor of China, but, assuming the white robe of a rahanee, spent her days in a forest, devoted to pious meditation. The mixture of ancient polytheism and Buddhism in the story was an apt illustration of the confused form of religion represented in the shrines.

Our visit was concluded by a sumptuous dinner at the tsawbwa’s house, the great point of etiquette apparently being to leave no part of the table unoccupied by dishes, save a margin for the guests to use their chopsticks. After dinner the tsawbwa introduced the subject of religion, and was much surprised at our not believing the doctrine of successive existences. Speaking of Gaudama, he distinguished him from Buddha, and was anxious to learn from us in what country he, Gaudama, was at present living.

The Buddhism of the Shans is, as has been already noticed, marked by great laxity among the phoongyees, and the most active religious feelings among the people belong to the belief in and worship of nats. During our stay, on the 13th of August, the fire festival of the Shans was celebrated, and about twenty bullocks and cows were slaughtered in the market-place; the meat was all speedily sold, part of it being cooked and eaten, while the remainder was fired out of guns at sundown, the pieces which happened to fall on the land being supposed to become mosquitoes, and those in the water leeches. Immediately after sunset the tsawbwa’s retainers began to beat gongs and blow long brass trumpets; after dark, torches were lit, and a party, preceded by the musicians, searched the central court for the fire nat, who is supposed to lurk about at this season with evil intent. They then prosecuted their search in all the apartments and the garden, throwing the light of the torches into every nook and corner where the evil spirit might find a hiding-place. Three other festivals are annually devoted to the nats of rain, wind, and cold.

The eclipse of the sun which happened on the 18th of August, commencing at 9.5 A.M., had been predicted by us at various places, and here also. The diminution of light was, as the Shans admitted, not sufficient to have called their attention to it, unless forewarned. The tsawbwa showed his usual intelligence by being able to use the telescope. As soon as he had satisfied himself that the eclipse had really commenced, he ordered his saluting guns to be fired, and the long trumpets to be blown, while, at his earnest request, we were obliged to order out the police guard to fire two volleys; all this was to terrify some monster that was threatening to devour the sun. The chief, however, listened attentively to our endeavour to explain the natural causes of the phenomenon, and even imparted them to the excited crowd which flocked eagerly about us.

Some of the khyoungs in the valley were altogether sacred to the Chinese deities Kwan-yin and Showfoo, the Prah, or god of the Yunnan Chinese, with various evil nats and famous teachers, such as Tamo, to the utter exclusion of any trace of the Buddhistic creed.

At a dilapidated little temple close to Hotha, dedicated to certain nats, the entrance was guarded by two horses, each with a horseman standing at its head. Similar figures of horses, tended by a man in Tartar costume, occurred in the khyoung at Muangla, and the reader may remember that the Manwyne women paid daily offerings of rice to the horse’s image in the khyoung at that town. The fact that the Shans are a race of horse-breeders and horsemen may account for the preservation of this curious relic of their pristine religion, along with the primæval propitiation of the dangerous nats, or powers of earth, air, and water.

The principal Buddhist khyoung of the valley, situated in the pretty walled village of Tsendong, is perfectly free from any admixture of their older superstitions. The tsawbwa, who acted as our cicerone, seemed very proud of the temple, which was declared to be very old. It is built on a low stone platform, surrounded by a narrow terraced verandah, the whole of the outside being roughly but skilfully carved. It contained richly gilt book cabinets, and elaborately carved altar-pieces, and might have been transported entire from the Burmese plains. The remains of an old and venerated phoongyee, who had died two months previously, lay in state under a double-roofed temporary pavilion, close to the khyoung. The sarcophagus, supported on two dragons, was a handsome structure, surmounted by a richly carved miniature pagoda. The ground had been levelled, and was kept scrupulously clean, and the whole enclosure carefully railed off. On a neighbouring terrace stood an octagonal zayat, enclosing a small pagoda. It was built almost entirely of wood, with five roofs, diminishing in size upwards, and capped by a golden htee. A series of open windows of carved wood-work ran round the building, and over each were two beautifully carved panels, representing a single object, as a bird, deer, plant, or bat. Each roof was raised on three projecting bearers, terminating in grotesquely carved heads. The enclosed pagoda was a square structure, with a delicately tapered spire reaching to the interior of the highest roof.

The presence of these purely Burmese buildings in the Hotha valley, while pagodas are altogether wanting in the valley of the Tapeng, is probably due to the vicinity of the ancient embassy route, but in 1769 the Burmese appealed to the existence of pagodas in this valley as a proof of their ancient right to include it within their boundaries.

The heavy rains which continued during our stay at Hotha delayed our progress, and at the same time prevented more complete explorations of the neighbourhood.

As already mentioned, we were to proceed over the Kakhyen hills, at the western end of the valley, the plan of crossing into Muangwan being impracticable, so far as we were concerned, although a Burmese surveyor was detached to examine the route. As before stated, we were debarred from even visiting the southern heights, but Mr. Gordon and I made an excursion to the eastern head of the valley, where it is closed in by a transverse ridge connecting the two ranges. A good road led to the ridge, which was crossed by a narrow track, the highest point not being more than four hundred feet above Hotha. A steep declivity led down into another valley, probably branching off from Muangwan. To the east-north-east, another valley could be descried, leading in the direction of Nantin, which lies one thousand one hundred feet lower. Through the mist and heavy rain, glimpses of high hills were dimly seen on every side, and we concluded that the Hotha valley, as a thoroughfare to Momien via Nantin, would present more difficult heights to be surmounted than the valley of the Tapeng.

We learned that from Old Hotha a road led to Muangla, reaching the Sanda valley by a gorge of lower elevation and more gradual descent on the northern slope than the route by which we had climbed up and scrambled down in our passage from Manwyne. Even an excursion, however, beyond the limits of the Hotha valley was rendered impossible by the presence of Li-sieh-tai and his force in Shuemuelong. We accordingly addressed ourselves to quit the pleasant quarters at Hotha, and recross the Kakhyen hills to the Burmese plain, all the chiefs of the hill tribes along the route having attended in person or by deputy at a meeting on August 22nd, when satisfactory arrangements had been made for our transit.

One gallon contains:—

49·7 grains of solid matter;

3·6 ” salts of alkalies, chloride of sodium;

19·7 ” silica, earthy salts, and oxide of iron;

Traces of sulphuric, carbonic, and phosphoric acids;

No nitric acid.