CHAPTER II.

BHAMÔ.

Arrival at Bhamô—Our quarters—The town—The Woon’s house—The Shan-Burmese—Kakhyen man-stealing—The environs—Old Tsampenago—Legendary history—The Shuaykeenah pagodas—The Molay river—The first defile—Delays and intrigues—Sala—The new Woon—Our departure—Tsitkaw—Mountain muleteers—The Manloung lake—The phoongyee’s farewell.

We found some difficulty in steering the long steamer through the channels, but anchored about 5 P.M. on the 22nd of January off the river front of Bhamô, in a very deep and broad channel. Our arrival attracted crowds, but the whistle and rush of steam drove many into a precipitate retreat. We had now reached our true point of departure. Whatever had been the uncertainties of the untried navigation of the river, the real dangers and difficulties of the attempt to penetrate Western China were now to begin. We bore the proclamation of the king commanding all Burmese subjects to aid us. But there was no governor of Bhamô to execute the royal orders, and the secret intentions or inclinations of the Burmese were yet to be tested. The difficulties of the unknown road over the Kakhyen mountains, the hostility or friendship of the mountaineers, and of the Shan population between them and Yunnan, were equally untried. Moreover, though it had scarcely been realised in all its bearings by our own British officials, Yunnan was no longer a well ordered province of the Chinese empire; it was disorganised by the successful rebellion of the Mahommedan Chinese, called Panthays by the Burmese, who had established a partial sovereignty, extending from Momien to Tali-fu. The frontier trade had been materially interrupted, partly by the desolation caused by the internecine warfare, and partly by the depredations of imperial Chinese partisans. Of these, the most dreaded leader was a Burman Chinese, known as Li-sieh-tai, a faithful officer of the old régime, who had established himself on the borders of Yunnan, and waged a guerilla war against the Panthays and their friends. His name is Li, and his so-called small name is Chun-kwo, while from his mother having been a Burmese, he is also known as Li-haon-mien, or Li the Burman. As having been raised to the rank of a Sieh-tai in the Chinese army, he was called Li-sieh-tai or Brigadier Li.[15]

In Bhamô itself there were a number of Chinese merchants, who were unlikely to favour any project which threatened to admit the hated barbarians to a share of their monopoly and profits. This may give some idea of the state of things which we found on our arrival. Our illusions as to a speedy or easy progress were soon dissipated, and after a formal visit from the two tsitkays, or magistrates, ruling the northern and southern divisions of the town, it became evident that we must prepare for a long stay at Bhamô. The royal order to provide transport had only been received by the Woon on the eve of his departure on his fatal expedition to Momeit. Nothing, therefore, had been done; nor could they venture to act until the new governor arrived. The next best thing was to insist on their carrying into effect the royal order to build a house for us, which had not been done. This they reluctantly performed, and in a few days a bamboo edifice was run up close to the Woon’s house, consisting of a central hall, with three bedrooms on either side, and a verandah at each end of the house. A small outhouse accommodated the servants and baggage, and the guard was quartered in an adjacent zayat; a tent pitched in front of the house served as a refectory. Till these quarters were prepared, we remained on board the steamer, receiving crowds of visitors. In the press a heavy log of timber fell on a little girl and fractured her thigh; she was at once carried on board, and the broken limb duly set. This incident speedily established the reputation of the foreign doctor, and for the rest of our stay patients flocked in every day, some coming from long distances, and blind and lame eagerly expecting to be made young and whole. A great deal of blindness had resulted from small-pox. Ophthalmia was also prevalent. A common affection was a form of ulcerous inflammation, chiefly on the legs, amongst those whose occupation led them into the jungles. This was so intractable as to incline one to attribute it to poisonous thorns; but subsequent personal experience proved that slight bruises and abrasions are most apt in this country to become painful and tedious. During the whole time no case of fever was treated, nor did any occur among our party of one hundred men. This speaks volumes for the salubrity of the place during the dry season. The highest temperature experienced was 80° Fahrenheit, the average maximum being not more than 66° Fahrenheit, while the nights were very pleasant, cooling down, if we may put it so, to fifty or forty-five degrees. Fever is rather more prevalent during the rains, when the Irawady rolls down a huge volume of water, a mile and half broad, and the low lands are submerged twelve to fifteen feet.[16]

But this is a digression somewhat professional, and it is needful to revert to the narrative and try to give the reader some notion of our surroundings and proceedings until we got away fairly on the march.

Bhamô, known by the Chinese as Tsing-gai, and in Pali called Tsin-ting, is a narrow town about one mile long, occupying a high prominence on the left bank of the Irawady. Instead of walls, there is a stockade about nine feet high, consisting of split trees driven side by side into the ground and strengthened with crossbeams above and below. This paling is further defended on the outside by a forest of bamboo stakes fixed in the ground and projecting at an acute angle. However formidable to barefooted natives, the stockade does not always exclude tigers, which pay occasional visits, and during our stay killed a woman as she sat with her companions. There are four gates, one at either end and two on the eastern side, which are closed immediately after sunset; a guard is stationed at the northern and southern gates, while several look-out huts perched at intervals on the stockade are manned when an attack of the Kakhyens is expected. The population numbers about two thousand five hundred souls, occupying about five hundred houses, which form three principal streets. There are many thickly wooded by-paths, and bridges over a swamp in the centre of the town, leading to scattered houses, dilapidated pagodas, zayats, and monasteries.

The street following the course of the bank, with high flights of steps ascending from the river, has a row of houses on either side, with a row of teak planks laid in the middle to afford dry footing during the rains. The houses of the central portion are all small one-storied cottages, built of sun-dried bricks, with tiled concave roofs with deep projecting eaves. Through an open window the proprietor can be seen calmly smoking behind a little counter, for this is the Chinese quarter, and the colony of perhaps two hundred Celestials here offer for sale Manchester goods, Chinese yarns, ball tea, opium, Yunnan potatoes, lead, and vermilion, &c. They also regulate the cotton market, and the traffic in this product, which is brought both from the south and the north, is carried on even during the rains. The head Chinaman, who is responsible for order amongst his compatriots, is a man of great influence. He and his fellow merchants, professing great friendship, invited us to a grand feast and theatrical entertainment given in the Chinese temple, or rather in the theatre which formed a portion thereof. We entered through what was to us a novelty in this country, a circular doorway, into a paved court. The theatrical portion of the building was over the entrance to a second court, facing the sanctuary, which is on a higher level. A covered terrace surrounded the holy place on three sides, with recesses containing seated figures nearly life size, with rubicund faces and formidable black beards and moustaches. Each of these was carefully protected from dust by being enshrined in a square box closed in front with gauze netting. Besides the theatrical entertainment, which was interminable, we were regaled with preserved fruits and confectionery, with tea and samshu, or rice spirit, followed by numerous courses of pork, fowls, &c. The staple of conversation was the dangers and impossibilities of getting through to Yunnan; every argument they could think of to induce us to abandon the idea of progress was then and afterwards employed. It can readily be imagined that the Bhamô Chinese traders viewed with utter dismay the prospect of Europeans sharing their trade; to their schemes of hindrance we shall again recur.

The rest of the townspeople are exclusively Shan-Burmese, living in small houses built of teak and bamboo, all detached and raised on piles. The Woon’s house, on a low promontory running out into the swamp behind the Chinese quarter, was a large tumbledown timber and bamboo structure; but its double roof and high palisade covered with bamboo mats marked the dignity of its occupier. A small garden overrun with weeds contained the remains of a rockery and fish-pond, and a neglected brass cannon, under a low thatched shed, guarded either side of the gate; in a large adjacent space stood the court-house. All the public buildings were then in a state of dilapidation and decay; this the inhabitants attributed to Kakhyen raids, destructive fires, decay of trade since the Panthay wars, and misrule. Evidence was not wanting in the numerous neglected pagodas and timber bridges, and in the ruinous and charred remains of what must have been handsome zayats, that Bhamô, in palmier days, deserved the eulogiums passed on it by Hannay and other travellers.

The Shan-Burmese seemed a peaceful, industrious class. In each house a loom is found in the verandah, and the girls are taught to weave from an early age. The women are always busy weaving silk or cotton putzos and tameins, preparing yarns, husking rice, or feeding and tending the buffaloes, besides doing their household duties. The men till the fields, but are not so industrious as the softer sex. A few are employed in smelting lead, and others work in gold, or smelt the silver used as currency. To six tickals[17] of pure silver purchased from the Kakhyens, one tickal eight annas of copper wire are added, and melted with alloy of as much lead as brings the whole to ten tickals’ weight. The operation is conducted in saucers of sun-dried clay bedded in paddy husk, and covered over with charcoal. The bellows are vigorously plied, and as soon as the mass is at a red heat, the charcoal is removed, and a round flat brick button previously covered with a layer of moist clay is placed on the amalgam, which forms a thick ring round the edge, to which lead is freely added to make up the weight. As it cools, there results a white disc of silver encircled by a brownish ring. The silver is cleaned and dotted with cutch, and is then weighed and ready to be cut up. Another industry is confined to the women, who make capital chatties from a tenacious yellow clay, which overlies this portion of the river valley, in some places forty feet thick; the earthenware is coloured red with a ferruginous substance found in nodules embedded in the clay.

From the same clay, a number of Shan-Chinese from Hotha and Latha make sun-dried bricks outside the town, and a colony of the same people sojourn every winter at Bhamô, making dahs, or long knives, which are in great demand. A number of Kakhyens are often to be seen near the town, bringing rice, opium, silver, and pigs for sale. Their chief object is to procure salt, for which necessary they are dependent on Burma. They are not allowed to encamp within the town, but are compelled to shelter themselves outside the gates, in miserable wigwams. The Burmese assigned as a reason for their exclusion their dread of the Kakhyen propensity for kidnapping children and even men, and also because a small party might be the precursors of a raid.[18] A few days after our arrival, four children who had been stolen were recovered. One of them was brought by her mother, to show the large round holes bored in the back of the ears as a sign of servitude. The other three were little fat Chinese children, and adopted by the head tsitkay. A curious illustration of their habits of man-stealing was also afforded us.

The Burmese interpreter found among the Kakhyens outside the town a man who privately told him that he was a kala, or foreigner, who had been ten years in slavery; having heard of the arrival of the kalas, he anxiously desired an interview. His features showed that he was a native of India, and his history, given in a jumble of Burmese, Kakhyen, and Hindostani, was as follows. Deen Mahomed, a petty trader from Midnapore, had come to Burma with nine others ten years before. They stayed a year at Tongoo, thence making their way up as far as Bhamô. In this neighbourhood, during a halt for cooking, all had gone to seek firewood save Deen Mahomed and another, who were in charge of the goods. A party of Kakhyens suddenly rushed out of the bush, and seized both men and goods. His comrade was taken away he knew not where, and he was carried off as a slave. A log of wood was fastened to one of his legs, and he was further secured by ropes fastened to this, and braced over his shoulders. This he wore for two months, during which time he was not made to work, but was guarded by a Kakhyen. He was then released on his promise to remain. A few days after, the village was plundered by a hostile tribe, but he and his master escaped to another village, where he was bartered for a buffalo to another man. His new master treated him well, but did not allow him to leave the hills, and after two or three years gave him a Kakhyen wife. He had almost forgotten his native language, but not his native country. As soon as he heard of our arrival, he resolved to ask our aid in his deliverance. We sent him among his fellow-countrymen of the guard, who clothed him, and he was installed as a groom, and taken with us as an interpreter. That his story was true, we had confirmation, as his quondam master preferred a claim for compensation for his loss.

The country behind Bhamô runs up to the base of the mountain wall in undulations so long as to present the general aspect of a level slope, covered with eng trees and tall grass. For about a mile outside the stockade, the surface is cut up by numerous deep jheels, evidently old backwaters of the Irawady, which once flowed in a long curve, marked by an old river bank, south-east of the town. The soil, especially in the hollows, is very rich, giving two crops of rice annually. Numerous legumes, yams, and melons, and a little cotton are grown, and the sandy river islands yield capital tobacco.

The edible fruits procurable are jacks, tamarinds, lemons, citrons, peaches, &c., and plantains are plentiful.

About a mile north of the town, the Tapeng river debouches into the Irawady, after flowing twenty miles through the plain as a quiet navigable stream, hardly recognisable as the furious torrent which rushes through the neighbouring gorge. During the dry season, it is one hundred and fifty to two hundred yards wide, and navigable only by boats, which convey a constant traffic between the Irawady and Tsitkaw, where the merchandise is transferred to and from mules. During the rains, the Tapeng is at least five hundred yards wide, and navigable for small river steamers up to this place.

Occupying the angle between the two rivers, the remains of an ancient city are still discernible, though completely overgrown by magnificent trees and thickets of bamboo and elephant grass. The broad wall, composed of bricks and pebbles, can be traced from the river banks at its northern and southern extremities, which are a mile apart. We followed one section for three quarters of a mile, and found it in some places thirty feet high from the bottom of the moat, which is still traceable. The ruins, which, to judge from appearances, are coeval with those of Tagoung, mark the site of the oldest Tsampenago. This city, according to tradition, quoted by the old phoongyee at Bhamô, flourished in the days of Gaudama. There is yet another ruined city of the same name on the other side of the Tapeng, which does not present the same appearance of great antiquity. Twelve miles to the east of Bhamô are the ruins of another city named Kuttha, while Bhamô itself has a predecessor in the village called Old Bhamô, near the foot of the Kakhyen hills, the former importance of which is witnessed by its ruined pagodas. Here too is that old brick building mentioned by Dr. Bayfield as probably the remains of the old English factory erected in the beginning of the seventeenth century. We have little but conjecture to guide us as to the vicissitudes of these ancient cities of the Shan kingdom of Pong. As elsewhere in Burma, each new founder of a dynasty seems to have transferred the seat of power to a new site. But the legend of the origin of Tsampenago, of which the history of Bhamô is a continuation, may be more interesting than dryasdust details of antiquity.[19]

Tsampenago is the Burmese form of a Pali name, Champa-nagara, from nagam, town, and Champa, the seat of a powerful kingdom, flourishing in the era of Gaudama, the ruins of which are still visible near Bhaugulpore, on the Ganges. Tsampenago, then, means the city of Champa.

The founder and first king of Tsampenago was Tsitta, and his queen’s name was Wattee. They were childless, which was a cause of great grief, and the queen prayed earnestly for an heir. A son was promised to her by a dream, in which the king of the Devas presented her with a valuable gem. Soon after this, the king’s brother Kuttha rebelled, and attacked the city with a great army. The king and queen fled for their lives to Wela, a mountain three thousand feet high, a day’s journey north of Tsampenago. They were pursued, but the queen escaped and was preserved by the nats, on the mountain, where her son was born and named Welatha. The king was taken prisoner and confined in chains. When Welatha was six years old, he saw his mother in tears, and by questioning her learned that he was a prince, and his father a captive. When he was seven, his mother yielded to his importunity, and sent him, with her royal ornaments, to visit his father. On approaching Tsampenago, he met his father being led out to execution. The brave boy stopped the procession, and revealed himself, offering to die instead of his father. Kuttha ordered him to be thrown into the Irawady. But the river rose in tremendous waves, the earth shook, and the executioners could not, for terror, obey the royal order. This being reported to Kuttha, he ordered that the prince should be trodden to death by wild elephants, but the beasts could not be goaded to attack him. A deep pit was dug and filled with burning fuel, into which the prince was cast, but the flames came on him like cool water, and the burning fagots became lilies. When Kuttha heard this, in his fury he had the young prince taken down to the Deva-faced mountain (second defile), and cast from the great precipice into the river, but he was caught up by a naga, and carried away to the naga country. The earth quaked, many thunderbolts fell, the Irawady rolled up its waves, and broke down its banks. Kuttha was seized with terror, and as he fled forth of the city gate, the earth opened and swallowed him up. Thereupon, the nagas brought back the young prince and his father, and they reigned jointly. Their first care was to seek for the queen, but on approaching the mountain of Wela, the flowers were few, and their fragrance gone, and the queen was found dead. History says nothing of their after reign, but records that in the 218th year of the Buddhist sacred era, in obedience to the command of the universal monarch, four pagodas were built in the kingdom of Tsampenago—the Shuaykeenah, the Bhamô Shuay-za-tee; Koung-ting, and two others. The next item of history states that in the year 400 of the era (probably the vulgar era of 638 A.D.) the succession of kings being destroyed, and the glory of the former rulers having departed, the tsawbwa Tholyen did not dare to live in the city; so he founded a new one at the village of Manmau, and made it his capital. Now man is Shan for village, and mau for a pot; thus Bhamô, or Manmau, signifies Potters’ Village, a name still justified by the pottery there manufactured. How Tsampenago was destroyed, is not historically certain, but a tradition exists among the Shans, that it was overthrown by an army of Singphos from the north-west. After Tholyen, twenty-three tsawbwas are said to have ruled in succession at Bhamô over a district comprising one hundred and thirty-six villages. The succession was then broken, and the country was ruled by Shan deputies. After this, tsawbwas were obtained from Momeit, who ruled over Bhamô till Oo-Myat-bung and his family were made slaves by the great Alompra about 1760. Ever since, the district has been governed by myo-woons appointed by the king of Burma. The first, Thoonain, settled the boundaries of the district, including only eighty-eight villages, the eastern and north-eastern boundaries being given as China.

The legend of Tsampenago records the erection of the Shuaykeenah pagoda, the name of which at least is preserved to the present day by the group of pagodas situated on an eminence north of Tsampenago. These are still the holy places of the neighbourhood, and are thronged with pilgrims at the March festival. The great gilded pagoda has been re-edified by royal bounty and popular offerings, but others are from time to time added by private votaries. Thus it was our good fortune to witness the laying the foundation of a votive pagoda at Shuaykeenah. A small square of ground, the exact size of the base of the intended pagoda, was railed off by a fantastic bamboo fence, two feet high, decorated with flowers and paper flags. A wooden pin, covered with silver tinsel, and bearing a lighted yellow taper, was fixed in the centre, and another about two feet from the south-eastern corner of the level plot; round the first a quadrangular trench, and a deep hole by the side of the other were dug and sprinkled with water. Eight bricks, each the exact size of one side of the trench, were prepared. On four the name of Gaudama was inscribed in black paint; on the others, a leaf of gold was placed on the centre of one, silver on the second, a square of green paint on the third, and red on the fourth, each having a border of green. A round earthen vase containing gold, silver, and precious stones, besides rice and sweetmeats, was closed with wax in which a lighted taper was stuck, and deposited in the south-east hole, by the builder of the pagoda, who repeated a long prayer, while the earth was filled in and sprinkled with water. This was an offering to the great earth serpent, in the direction of whose abode the south-east corner pointed. It is an interesting relic of the snake worship once so prevalent among the Shan race to the south, which, like nat worship, has been incorporated in Buddhism. Another instance is afforded in some of the Yunnan shrines, where the canopy over Buddha is supported by many-headed snakes, as occurs in some Indian temples. In the next part of the ceremony, the depositing of the bricks in the trench, the Shan was assisted by his grandmother, wife, and daughter; he knelt at the north, faced by his wife, his daughter on his right hand, and the grandmother on the left. The silvered brick, with a lighted taper on it, was handed to the old woman, who raised it over her head, and, devoutly murmuring a long prayer, placed it in the trench; the wife did the same with the red brick and its taper, and the daughter followed with the green, while her father took the gold one. The girl, in raising her brick, burst out laughing, amused, as we were told, at having forgotten her prayers. The four bricks having been properly deposited, the others were next laid in order, the sacred name downwards, and a layer of cloth spread over all. Earth was then thrown in and sprinkled with water, and the hole having been filled up, the ceremony was over.

Four miles above Shuaykeenah and the mouth of the Tapeng, the Irawady receives the waters of the Molay. It is a narrow stream, rising in the Kakhyen hills, with a course of ninety-six miles, for thirty of which it is navigable during the rains, and a small boat traffic exists, chiefly for the conveyance of salt.

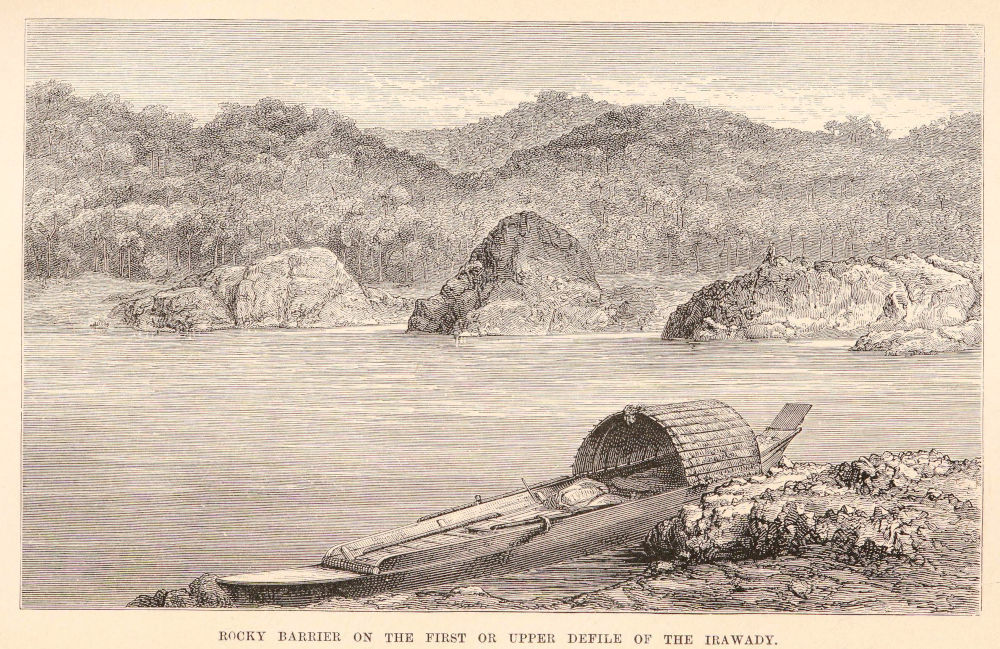

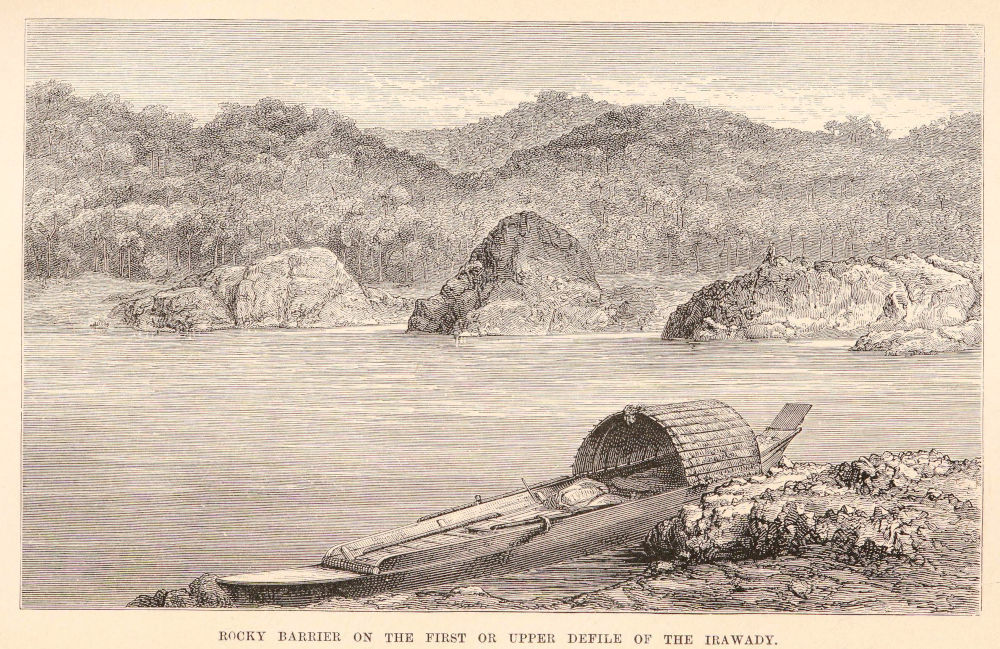

While our leader was engaged planning for our departure with the officials, three of us made a hurried excursion to the first khyoukdwen, or defile. This portion of the river commences a few miles above Bhamô, and extends for twenty-five miles, nearly to Tsenbo.

Between these two points the river flows under high wooded banks. At the lower entrance, the channel is one thousand yards broad, but gradually narrows to five hundred, two hundred, and even seventy yards, as the parallel ranges approach each other. As we ascended, the hills rose higher and closed in, rising abruptly from the stream and throwing out a succession of grand rocky headlands. We moored for the night off a Phwon village standing on a cliff eighty feet high, just above the first so-called rapids. The next day, after we had proceeded about seven miles, we came to a reach in which the river flowed sluggishly between two high conical hills, which seemed to present no outlet. The quiet motion and deep olive black hue of the water suggested great depth.[20]

ROCKY BARRIER ON THE FIRST OR UPPER DEFILE OF THE IRAWADY.

This reach extended about one mile and a half, with a breadth of two hundred and fifty yards, closing in at the upper end, where the channel is broken up by rocks jutting out boldly, and approaching each other within eighty yards. A pagoda, apparently of great age, perched on a small isolated rock, rising about forty-five feet from the stream, seemed to indicate the limit of the rising of the waters, as it could not have withstood the flood. This rocky reach stretches a mile in a north-north-westerly direction, and terminates abruptly in an elbow, from which another clear reach, overhung by precipitous but grassy hills, extends east-north-east.

This bend of the river is one of the most dangerous parts, owing to numerous insulated greenstone rocks which stretch across it, exposed twenty feet and more in February. Owing to the sudden bend, the current rushes between them with great violence, but we found no difficulty in effecting a passage for our boats. Telling evidences were not wanting in the high-water mark, twenty-five feet above the then level, and in the shivered trunks of large trees and debris of branches heaped in wild confusion among the rocks, that the body of water pouring through the narrow gorge must in the rains be enormous and of terrific power. The navigation, with the present obstructions unremoved, would be impossible for river steamers, but engineering skill could speedily render the water way practicable if desired for traffic. We had not time to ascend to the northern entrance of the defile, where the river, unconfined by the hills, is again a majestic stream half a mile in width. We could only look, and long for an opportunity of exploring its course upwards to the unknown regions whence it rolls down its mighty flood. The problem of the Irawady’s source and course has yet to be solved; but we had to return to Bhamô, expecting the solution of our perplexities, as to how and when we should reach Yunnan.

Four weeks had now been spent by our leader in a fruitless attempt to get the tsitkays to assist in making the necessary arrangements. What between the novelty of their first introduction to enterprising Englishmen, their dread of acting till the Woon arrived, and last, though not least, their fear of offending the influential Chinese, they could do nothing, nor give any information. As the arrival of large Shan caravans and companies of trading Kakhyens proved, all routes were not closed. The magistrates admitted a small trade existed by the Tapeng and Ponline route; by this route it was decided that we should go. It soon became known to our leader that the Chinese merchants, failing to deter us from proceeding, had taken more active measures. They had written to the Kakhyen tsawbwas, desiring them to withhold assistance, and they further intrigued with the imperialist officer Li-sieh-tai, who at this time threatened the road to Momien and Tali-fu, entreating him to cut off the expedition en route. The turning-point of our fortunes had now arrived. We could gain no exact information as to the political relations of the Shans, and only knew that the Panthay government extended to Momien, which was believed to be the residence of Mahommedan chiefs of importance.

Major Sladen, with promptness and decision, resolved, unknown to all, to outwit the Chinese. He despatched letters to the chiefs of Momien, explaining the peaceful objects of the mission, and the approbation given to it by the Burmese government under our treaty, and pointing out the advantages of opening the direct trade. These letters, with copies of the treaty and proclamation, were secretly sent off by three Kakhyens from the southern hills, who had attached themselves to our interest.

The next character claiming our attention was Sala, the Kakhyen chief of Ponline, who came to Bhamô at the request of Sladen, after refusing to comply with the order of the tsitkays. He visited us attired as a mandarin of the blue button, and attended by six or eight armed followers. He carried a gold umbrella, which he had received from the king of Burma, with the title of papada raza, or mountain king. There was nothing regal in his aspect or bearing. He was a tall, thin man, with a contracted chest, long neck, very small and retreating forehead, while his oval and repulsive visage was adorned with high cheek-bones, oblique eyes, and a depression instead of a nose. During the interview, when all the Burmese officials were present, he sat ill at ease, with his eyes bent on the floor. We received him as an independent chief, with the escort drawn up under arms in his honour. But little information was procured, as the interpreter, a village tamone, could not be persuaded to give correct versions of the chief’s short and almost monosyllabic answers. So Sladen brought the interview to a pleasant close by offering a friendly cup of eau de vie. This seemed to suit the chief, and he and his retinue finished a bottle of brandy, and asked for more. His parting words were, “Remember the brandy, and send it to me quickly.”

The following day, at a private interview, the chief threw off his former reserve, which he said had been forced on him, as he could not afford to offend the Bhamô Chinese. It was his own wish to assist the mission, but he stipulated for a small Burmese escort, to show that we had the full support of the king. He engaged to assemble a hundred mules at Tsitkaw, a village on the right bank of the Tapeng twenty-one miles distant; thence he undertook to conduct us safely to Manwyne, the first Chinese Shan town, and boasted himself as the greatest chief on the route, and on good terms with all the tsawbwas.

The new Woon arrived on the 20th of February, but declined to land for three days, as they were dies nefasti. In the meantime he sent word that we might have boats to take the baggage to Tsitkaw, but advised us to wait until he had fired his guns, and brought in the various Kakhyen chiefs. The day after his landing, Sladen, with Sala, visited him, and the Ponline chief asked for a Burmese guard, alleging as a precedent that a guard had been sent up with the king’s cotton. The Woon, however, declared it to be quite unnecessary and uncalled for, and told the chief that the cases were quite different. The tsawbwa then consented to take us on without the guard, but told the Woon that he had received threatening letters from the Chinese. The Woon admitted his knowledge of the Chinese opposition, and promised to admonish the head Chinaman at Bhamô that he would be held responsible for our safety. The morning after the Woon arrived, he proceeded in state to the court-house, escorted by two hundred men. He wore the fantastic dress of a Burmese prince, a short tight richly coloured coat covered with gold tinsel, with two enormous wing-like epaulettes, and a tall gilt hat like a fireman’s helmet, surmounted by a pagoda-like spire. His appointment was read, and the guns fired, after an hour had been spent in driving home the powder and cartridge of green plantain leaf. Our baggage was despatched the next day, but two difficulties remained. We had no Kakhyen interpreters, and the rupees, which were said to be useless in the Shan country, had not been changed, for no country silver was to be found in Bhamô, a mysterious and suggestive fact. But these were not held sufficient to delay our departure, which took place on the morning of the 26th of February. Our want of a guide was removed by an accidental meeting in the street with the head jailor, a good-natured Shan, whom Sladen induced to guide us to Tsitkaw, promising to screen him from any displeasure of the authorities. Although the distance is only twenty-one miles, the loss of time caused by ferrying our party of one hundred men over the Tapeng compelled us to halt at the village of Tahmeylon, where we put up in a small monastery. Early the next morning we started, skirting the Tapeng through tall grass, with occasional rice clearings. At the junction of the Manloung river with the Tapeng, a number of ruined pagodas marked the site of the second town of Tsampenago, built at a much later date than that near Bhamô.

By noon we reached Tsitkaw, and were received inside the low stockade by the Burmese officials and a miserable guard armed with rusty flint muskets, who garrison this as a customs station. We were conducted to a small barn-like zayat, which had been cleaned out for our use. Inquisitive natives speedily sought to force their way in, and had to be kept at bay by armed sentinels, though with caution. And we were requested to have a guard under arms all night, to protect our property against thieves, and perhaps ourselves against tigers, which occasionally overleap the stockade. In the morning, the Kakhyen tsawbwas, or chiefs, and pawmines, or headmen, of Ponline, Tahlone, Ponsee, and Seray, through whose lands lay the route to Manwyne, appeared to take charge of ourselves and baggage. As the Shan-Burmese of Tsitkaw and other villages near the hills keep on good terms with the highlanders, the chiefs showed no timidity of the Burmese officials; they made themselves quite at home, and asked for brandy; under its genial influence a formal assent was soon given to our passage through their territories.

The first process was to collect all our baggage, that it might be passed in review, and divided into small loads. Outside Tsitkaw, we had passed an enclosure in which were about a hundred men, chiefly Shans, with a few Kakhyens. These fellows had jeered at us in passing, and it was by no means reassuring to learn that this unmannerly mob consisted of the mule owners, as restive and untractable as their beasts. Each man owned from one to a dozen mules, and looked after his own interests without regard either to his employer’s or the rest of the caravan. The consequent shouting, disputing, and almost fighting that ensued as each helped himself to the packages that seemed desirable baffled description. At last all the baggage was distributed in little heaps, and each man marked off the number of mules required on a primitive tally, formed from a piece of bamboo, which he broke across into a corresponding number of joints, and put up carefully against the day of reckoning.

The next morning witnessed another scene of confusion and quarrelling, as the panniers or pack-saddles were brought in order to have the loads adjusted. The packs are secured to cross-trees, which fit into transverse pieces of wood, fixed in the saddles; and a band passed in front of the mule’s shoulders keeps all firm in its place. When the burdens had been arranged, it appeared that there were more mules than loads, and the disappointed proprietors furiously disputed the possession of their lots with their more fortunate competitors; hands were repeatedly laid on the hilt of the dah, but all ended in bluster, and finally the loads were arranged. When all seemed ready for the morrow’s starting, the choung-oke, or bailiff of the river, appeared on the scene, accompanied by several Kakhyens, and informed us that March 1st, being the 9th of some Kakhyen month, was an altogether ill-omened day to commence any undertaking. This Burmese official further confidentially informed Sladen that there was a quarrel brewing between the muleteers and the chiefs, which would break out before long; but he was disconcerted by the prompt action of the leader, who sent for the chiefs, and, assuring them of his confidence, said that he would abide by their arrangements for the transport. To this they replied that we were their brothers, and that they would be true to us for ever. The enforced delay at this place enabled us to make a short excursion to the Manloung lake, about one mile and a half distant. I went all round it in a small canoe, which held three people with difficulty. The western bank is high and wooded, but broken by two channels, through which the Manloung stream issues, uniting below a small island, on which stands a Shan village of the same name. Besides this, there is another island, and a village named Moungpoo. The high bank is continued on the north, beyond the lake, as a prominent ridge covered with tall trees, extending in a bold sweep to the foot of the hills; it appeared evidently to be an old river bank, and that the lake marks what was once the course of the Tapeng. The Manloung stream falls into a remarkable offshoot of the main river, which afterwards rejoins the Tapeng by several channels. This stream is deep and rapid, and supplies several irrigating water-wheels. The lake is two miles long and a mile broad, and according to native accounts very deep. To the east extended a succession of swamps, hidden under a luxuriant growth of high grass; careful search discovered no springs or streams as sources of supply, although doubtless the former exist, as there is a constant outflowing of water. It is probably also a reservoir, filled annually by the overflow of the Tapeng, which during the rainy season frequently floods the level plain to a depth of two feet for some days at a time, the flood suddenly rising and as suddenly subsiding.

Manloung contained about eighty houses, and the women at this time were all busily engaged in weaving cloth from cotton procured from the Kakhyens, who grow it on the hills. The village boasted of a large and flourishing monastery, far superior to any to be seen at Bhamô, and with a large number of resident pupils. The dormitory was exhibited with pride by the chief phoongyee; the beds were neatly arranged along one side of the room, each possessing a nice clean mattress and coverlet and superior mosquito curtains.

Thence we returned to Tsitkaw, where the filthy disregard of decency exhibited by the drunken highland chiefs, which we were obliged to tolerate, made our enforced sojourn still more insupportable; and an additional source of anxiety was furnished by the information, imparted by Sala, that Moung Shuay Yah, our Chinese interpreter, was really in collusion with the hostile Chinese.

Daylight on the 2nd of March saw us all on the qui vive in expectation of an early start, but the mule-men, at nine o’clock, had not eaten their rice, and then came a demand for an advance of mule hire; a previous request for salt to be distributed to the people of villages en route had been complied with, but no sooner had the baskets containing it been brought in front of the house than the men helped themselves at discretion, and no more was heard of it. An hour was now spent in the distribution of five hundred rupees, which were laid out on a mat, while the eagerness with which the recipients gathered round and handled the silver spoke volumes as to their greed for coin. One of the tsawbwas had been seen eagerly watching Sladen’s private cash-chest, and asked in the most pressing manner to be allowed to take charge of it, while another dogged the footsteps of Captain Bowers’ servant, endeavouring to coax him into entrusting his master’s fowling-piece to his care.

During the morning the phoongyee of an adjoining khyoung arrived to say farewell. He had been a constant visitor, and the kind reception given him, and the toleration of his curiosity, which showed itself by wandering about and prying into everything, had quite won his heart. He was far superior to the usual run of Shan phoongyees, who, according to Burmese Buddhism, are lax and unorthodox in practice and doctrine. He spent much of his time in missionary visits to the ruder villages, whose inhabitants he hoped to convert to conformity with stricter religious rules. By way of a parting gift he presented each of us with some sweet scented powder and a few fragrant seeds or pellets, which he declared to be a sovereign remedy for headache or fever, “contracted by smelling culinary operations!” His advice to Sladen at parting was so shrewd and characteristic as to deserve quoting. “We have met before in a former existence, and it is by virtue of meritorious acts there done that I am privileged to meet you again in the present life, and advise you for your welfare. Wisdom and prudence are necessary in all worldly undertakings; use then special care and circumspection in your present expedition; your enemies are numerous and powerful. We shall all hail the reopening of the overland trade with China. The prosperity of the priesthood depends on the condition of the country and the people; what is good for them is also good for religion.”