CHAPTER III.

KAKHYEN HILLS.

Departure from Tsitkaw—Our cavalcade—The hills—A false alarm—Talone—First night in the hills—The tsawbwa-gadaw—Ponline village—A death dance—The divination—A meetway—Nampoung gorge—A dangerous road—Lakong bivouac—Arrival at Ponsee—A Kakhyen coquette.

Almost at the last moment before setting out, while lists of the muleteers were being taken, in order to ascertain their respective chiefs, so as to know who should be held responsible, in case of default or robbery, the tsawbwas of Ponsee and Talone discovered that Sala, when at Bhamô, had received a musket as a present. Their informant was the treacherous Moung Shuay Yah, who instigated them to stand on their dignity and demand a similar gift. Compliance was impossible, so they refused their services, and prowled about in sneaking silence, ostentatiously taking lists of ourselves and of our baggage. By two o’clock a start was fairly effected, although our arrangements were by no means as complete as they might have been; but as it was settled that we should only proceed as far as Ponline village, about twelve miles distant, it was better to start than risk further delay. There was something outrageously wild in the irregular confusion of our exodus from Tsitkaw, which, though perhaps orderly according to Kakhyen ideas, presented no trace of system to our uninformed minds. The three Kakhyen chiefs led the way, followed by the unwieldy cash-chest, borne by eight men, and guarded by four sepoys; then came the long straggling caravan of a hundred and twenty mules, travelling just as it suited the peculiarities of each beast and its driver. Our police escort marched steadily on, headed by the jemadar, at whose side appeared his wife, looking like a true vivandière, her slim figure becomingly attired in a blue silk padded jacket, and trousers tucked up to the knee, with a red silk handkerchief for head-dress; with a Burmese dah and bag slung over her shoulders, and her shoes tied behind her back, she was evidently prepared for all dangers and fatigues.

We mounted our ponies and rode forward over the level plain before us; stretching north-east and south-west, rose the long undulating outline of the Kakhyen mountains, broken here and there by huge domes or pointed peaks, rising to five and six thousand feet. On our right flowed the Tapeng, gradually calming its waters into a placid stream, after having emerged as a foaming torrent from the mountain barrier. At the village of Hentha the route diverged from the river, and half a mile further we passed the long, straggling, but populous village of Old Bhamô, embosomed in a dense grove of bamboos and forest trees. Outside the village stood a solitary and almost ruined pagoda, the advanced outpost, on this side the river, of Burmese Buddhism, for none of these religious edifices are found among the Kakhyen hills.

Four miles’ ride through a succession of level swampy patches of paddy clearings, and grassy fields intersected by deep nullahs, brought us to the village of Tsihet, on slightly undulating ground. At this point the route turned almost at right angles, to ascend the hills, and here the three tsawbwas were seated in deep and excited consultation, apparently waiting for us. We had outstripped most of the convoy, and as Sladen rode up, Sala exclaimed, pointing to the hill-path, “All right, go on, and don’t be afraid.” His words were less intelligible than those of the Talone tsawbwa, who asked in an injured tone, “When are you going to give me that gun?”

We ascended about five hundred feet, over a series of rounded hills, distinct from the main range, but connected with it by spurs, up the slope of one of which we were slowly climbing, when a shot was heard in front. Sladen, the superior powers of whose pony had taken him ahead, waited until the others joined him, and another shot and then four reports together were heard, but no bullet whizzed near. A spear was picked up in the path, which a Burmese syce alleged to have been thrown from the jungle at the passing travellers; but his evidence was doubtful.

We all proceeded as if nothing had happened, but our Kakhyens, some fifty of whom were ahead, gathered round, flourishing their dahs and yelling like fiends, to assure us of their determination to protect us. A little further on we came upon two Kakhyens of our party, standing in an open by the roadside, one armed with a cross-bow and poisoned arrows, and the other with a flint musket. By signs they tried to convey to us that some evil-disposed mountaineers had hidden themselves at this spot, and had fired on them, but that on their returning the fire, the enemy had “bolted” down the hillside. We had our own opinion that the supposed attack was an ingenious ruse to try our mettle, and that most of the shots were fired by our half intoxicated muleteers, who evinced no sort of fear or misgiving. One of them, mounted on a mule, and armed with a long dah and matchlock, proved himself more dangerous as a friend than all the supposed enemies. He kept rushing backwards and forwards on a path scarcely wide enough in some places for a single pony; now he flourished his long sword in a reckless manner, and then fired his matchlock over the head of Sladen, who was in front, reloading and firing over his shoulder with a rapidity wonderful in a man so drunk as to be beyond reason. Judicious praises of his dexterity and a promise to refill his powder-horn at the next village were necessary to prevent him from becoming suddenly quarrelsome and dangerous.

From the summit of the spur fifteen hundred feet high, we descended by a rough, slippery path, the bed of a dried-up watercourse, to a level glen of rich alluvial land, and thence climbed another spur to a height of two thousand feet, whence a slight descent brought us to a long ridge, on which were situated the villages of Talone and Ponline. Approaching the first-named, we were requested to dismount, as Kakhyen etiquette does not admit of riding past a village. We led our ponies through a grassy glade, surrounded by high trees, and sacred to the nats. At one side stood a row of bamboo posts, varying in height from six to twenty feet, split at the top into four pieces, supporting small shelves to serve as altars for the offerings of cooked rice, fowls, and sheroo, wherewith the demons are propitiated. Before each altar were placed large bundles of grass, and a few old men were kneeling, muttering a low chant.

Leaving Talone on an eminence to our left, we remounted and descended a little distance through deep ravines, in secondary spurs, and, after a short ascent, traversed a tolerably level pathway, and another short rise brought us to our halting-place, the village of Ponline, lying two thousand three hundred feet above the sea. The rocks exposed were all metamorphic, consisting chiefly of a grey gneiss or red granite, and a hornblendic mica schist, huge rounded boulders of which latter were strewn on the hillsides. The hills were covered with a dense tree forest, largely intermixed with bamboos. It was already dusk when we arrived, but the moon shone brightly, and a pawmine conducted us to a house, swept and made ready for us. Like all Kakhyen houses, it was an oblong bamboo structure, with closely matted sides, raised on piles three feet from the ground. The roof thatched with grass sloped to within four feet from the ground; the eaves, propped by bamboo posts, formed a portico, used as a stable at night for ponies, pigs, and fowls, and as a general lounge by day. Notched logs served as stairs to ascend to the doorway in the gable end. On one side of the interior was a common hall, running the whole length of the building. On the other was a series of small rooms, divided from each other by bamboo partitions; a second doorway or opening at the further end was, as we afterwards learned, reserved for the use of members of the family, or household, none others being allowed to enter thereby, on pain of offence to the household nats. Chimneys and windows there were none, and the walls and roofs were blackened with smoke. In the common hall and in each room there was an open hearth sunk a little below the flooring, the closely laid bamboo work being covered with a layer of hard-pressed earth.

Only a portion of the baggage mules had arrived, and the bedding of several members of the party was among the missing property. Rumours were also afloat that robbers had succeeded in driving off eight mules, if not more, and altogether the first night in Kakhyen land seemed to some of the party inauspicious; but we made the best of it, and, having taken possession of our strange quarters, were presently joined by Williams, who had been detained taking the altitudes. He contributed the news that after leaving Talone a shot had been fired at Sala, who was in front of him. We strolled out in the pleasant night air, and admired an animated group of fair Kakhyens, busily pounding rice by moonlight. The paddy was placed in a rude mortar, or rather a cavity hollowed out in a log, and two girls stood opposite each other wielding heavy poles, four feet long. These were plied alternately, the heavy dull thud of the pestle forming a bass to the treble of a low musical cry, emitted at each stroke by the fair operators, while their bell girdles tinkled a pleasant accompaniment. These girdles marked their rank, only the daughters of chiefs being allowed to wear these musical ornaments.

An old woman beckoned Sladen to follow her, and conducted him to a house, which proved to be that of Sala, who received him most hospitably, making him share his carpet, while his guide, the tsawbwa’s wife, and her family brought successive relays of bamboo buckets, filled with sheroo, or Kakhyen beer.

At last, having divided what bedding there was, we settled ourselves to sleep, leaving it for the morrow to confirm or dissipate the fears excited by the non-arrival of guard, cash-chest, and baggage.

Our slumbers were, however, disturbed by loud shouts, repeated from height to height, which seemed to be the “All’s well!” of native guards, posted round the village to watch over our safety.

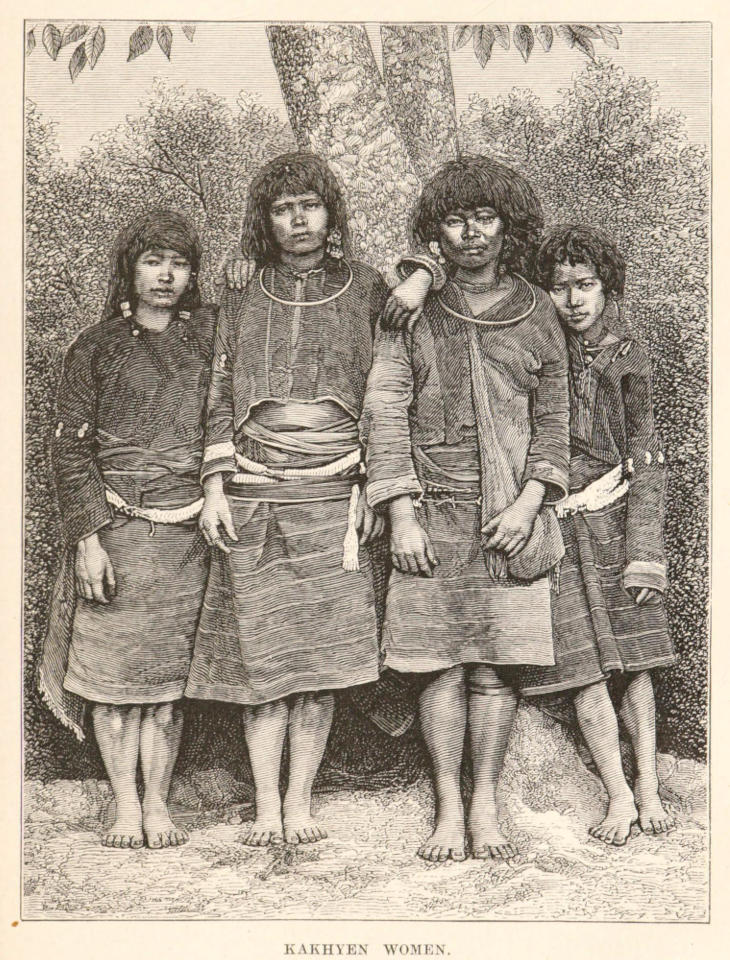

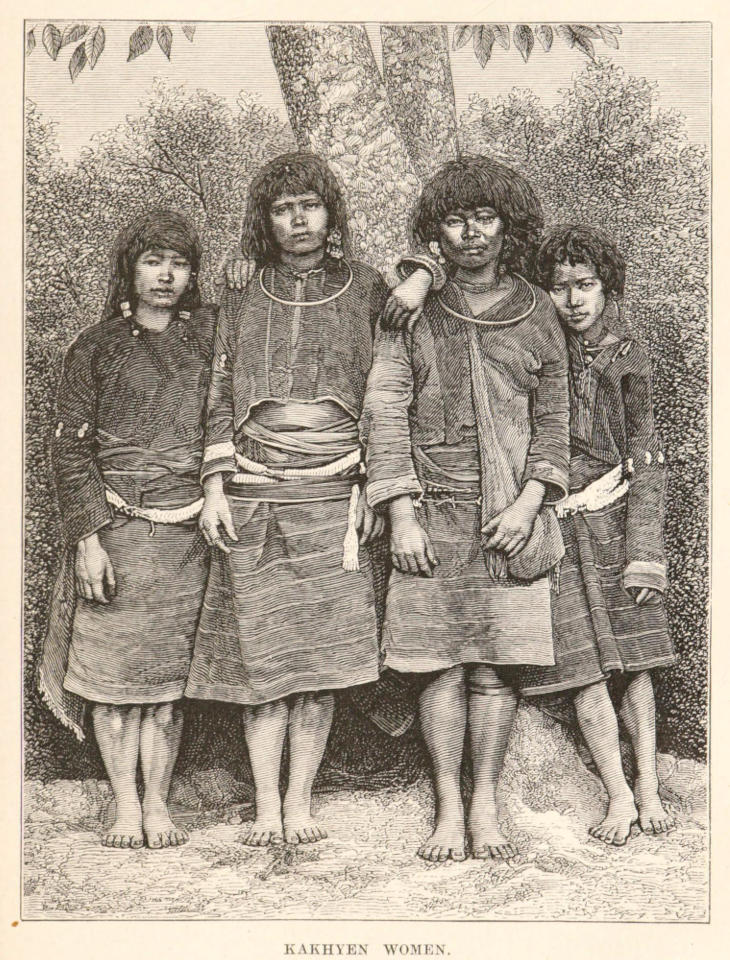

In the morning a large capon and a supply of beer arrived, as a present from the chieftainess, and later on she herself with her daughters and retinue came in state. She was a short matronly-looking woman, with an intelligent expression of countenance and good features, but for her high cheek-bones and slightly Chinese eyes. Her costume was of course the perfection of highland full dress, and, though singular, by no means unbecoming. The head-dress was the most striking part of it, consisting of blue cloth, wound round and round in a sort of turban, so as to form an inverted cone, towering at least eighteen inches above her head. Her upper garment was a sleeveless black velvet jacket, ornamented with a row of large embossed silver buttons running round the neck and continued down the front; besides these, circular plates of chased and enamelled silver, three inches in diameter, arranged in rows down the front and back seams and around the skirt, made the garment almost resemble a cuirass. The dress was completed by a single kilt-like petticoat, composed of a dark blue cotton cloth, with a broad red woollen border, wound round the hips, and reaching a little below the knee. One end was tastefully worked with deep silken embroidery, and carefully disposed, so as to hang gracefully on one side. A profusion of fine ratan girdles round the waist supported the kilt and filled up the void between it and the jacket; and, by way of stockings, a close-fitting series of black ratan rings encircled her legs below the knee. Her rank was marked by two large silver hoops round her neck, and a necklace of short cylinders of some red clayey material, intermixed with amber and ivory beads. These cumbrous ornaments are permitted only to the wives and daughters of tsawbwas and pawmines. Two silver bracelets on each arm, and long silver tubes worn in the lobes of the ears, completed her splendour. Her little daughters, besides the distinctive girdles of black beads, and silver bells, each containing a small free pellet, which tinkled pleasantly to every motion of the wearer, wore broad waist-belts ornamented with several rows of cowrie shells. Our visitor brought us goose eggs and sheroo, and apologised for not having more to offer, but promised to send us every day something to eat. Her goodwill was rewarded by presents of silk handkerchiefs and red cloth, and a gorgeous table-cloth, the splendour of which and her joy, when Sladen presented it to her, left her perfectly speechless.

KAKHYEN WOMEN.

During the day the missing mules and baggage began to arrive, the drivers having camped for the night at various places in the neighbourhood, and early in the afternoon the guard marched in, but without the cash-chest. The jemadar reported that he had remained in charge of it at Talone, where he had been obliged to leave it, together with the missing eight mules and their loads. The tsawbwa, who with his people and the Chinese interpreter, Moung Shuay Yah, had spent the night in drinking, refused to let either cash-chest or baggage proceed. The guard had been unable to obtain any food till before starting this morning, and one of the sepoys who had rashly indulged in excessive draughts of water had been seized with sickness, and died in two hours.

On the receipt of this news of the unaccountable conduct of the Talone chief and Moung Shuay Yah, Sala despatched his own son with positive orders for the instant release of the porters and drivers, and pending their arrival, we sallied forth to view the village and its surroundings. The houses were situated at short distances from each other in a deep hollow, thickly wooded with magnificent oaks and a few palms (Corypha), and very fine screw-pines, or pandani, one fallen stem of the former being fully sixty feet in length. Immediately over the village towered a bold rounded summit of the main range two thousand feet above us, halfway up the side of which a large conical Khakyen grave formed a prominent object; in shape it so strongly resembled a Burmese pagoda as to suggest an imitation. In the village very fine plantains were cultivated, and the sides of the spurs below were extensively cleared for rice and other crops. From the ground behind the tsawbwa’s house, we obtained a splendid view of the lofty hills on the southern side of the Tapeng valley, many of which appeared to rise to a height of six thousand feet above the river, cultivated and dotted with villages almost to the very summits.

In the course of our ramble we were attracted to one house by the sound of drumming; outside the portico, some men were sitting cooking chickens, which had been merely stripped of their feathers, but not otherwise cleaned. Having asked and obtained permission, we entered the common hall, round which men, women, and children were dancing, each carrying a small stick, with which they beat time, as they circled round with measured steps, curiously combining a prance and a side shuffle. The instrumentalists were a man and a girl, who vigorously beat a pair of drums, while ever and anon the dancers burst out into loud yells, and quickened the speed of their evolutions. We at first sat gravely on the logs, brought by a smiling girl, but were presently invited by signs to take our places in the dance; accordingly we stood up and went round, but had scarcely taken two turns when the whole party rushed, yelling loudly, out of the house, the leader flourishing his stick wildly, as though clearing the way. Much puzzled, we returned into the house, and found the corpse of a child, laid in a corner carefully screened off, and the poor mother wailing bitterly by its side. The festivity turned out to be the death dance, to drive away the departed spirit from hovering near its late tenement, and our exertions were believed to have mainly contributed to the speedy and happy result; so at least we were made to understand by our hosts, who hastened to refresh us with sheroo, served in cups ingeniously improvised out of plantain leaves. We paid our footing in silver, and departed with a feeling that even the entente cordiale we desired to establish with the Kakhyens hardly demanded an active participation in death-dances.

The next day Sala’s son arrived with the cash-chest and the missing mules from Talone; but the boxes had been opened, Sladen and Bowers had each lost a canteen, well stocked with knives and forks, and the mule-men had further helped themselves to all eatables. They had, however, shown a laudable consideration, for in one of Stewart’s cases was a bottle of port wine, which they had opened by pushing in the cork; not relishing the contents, they had carefully cut and fixed in a wooden stopper to prevent waste!

Sladen assembled Sala and the other chiefs, and distributed salt, cloth, and some yellow silk handkerchiefs, which were highly prized. Sala delivered a public exhortation, enjoining fidelity on all; in private he communicated the necessity of propitiating the nats, and requested our attendance at a ceremony which was to take place that night, for the purpose of ascertaining the will of the demons, by the medium of a meetway, or diviner.

Accordingly after dinner we all adjourned to the hall of the tsawbwa’s new house, and, reclining on mats brought by his wife, chatted for some time with the chiefs and headmen assembled round the fire.

The meetway now entered, and seated himself on a small stool, in one corner, which had been freshly sprinkled with water; he then blew through a small tube, and, throwing it from him with a deep groan, at once fell into an extraordinary state of tremor, every limb quivered, and his feet beat a literal “devil’s tattoo” on the bamboo flooring. He groaned as if in pain, tore his hair, passed his hands with maniacal gestures over his head and face, then broke into a short wild chant interrupted with sighs and groans, his features appearing distorted with madness or rage, while the tones of his voice changed to an expression of anger and fury. During this extraordinary scene, which realised all one had read of demoniacal possession, the tsawbwa and his pawmines occasionally addressed him in low tones, as if soothing him or deprecating the anger of the dominant spirit; and at last the tsawbwa informed Sladen that the nats must be appeased with an offering. Fifteen rupees and some cloth were produced. The silver, on a bamboo sprinkled with water, and the cloth, on a platter of plantain leaves, were humbly laid at the diviner’s feet; but with one convulsive jerk of the legs, rupees and cloth were instantly kicked away, and the medium by increased convulsions and groans intimated the dissatisfaction of the nats with the offering. The tsawbwa in vain supplicated for its acceptance, and then signified to Sladen that more rupees were required, and that the nats mentioned sixty as the propitiatory sum. Sladen tendered five more with an assurance that no more would be given. The amended offering was again, but more gently, pushed away, of which no notice was taken. After another quarter of an hour, during which the convulsions and groans gradually grew less violent, a dried leaf rolled into a cone, and filled with rice, was handed to the meetway. He raised it to his forehead several times, and then threw it on the floor; a dah, which had been carefully washed, was next handed to him and treated the same way, and after a few gentle sighs he rose from his seat, and, laughing, signed us to look at his legs and arms, which were very tired. The oracle was in our favour, and predictions of all manner of success were interpreted to us as the utterances of the inspired diviner.

It must not be supposed that this was a solemn farce, enacted to conjure rupees out of European pockets; the Kakhyens never undertake any business or journey without consulting the will of the nats as revealed by a meetway, under the influence of temporary frenzy, or, as they deem it, possession. The seer in ordinary life is nothing; the medium on whose word hung the possibility of our advance was a cooly, who carried one of our boxes on the march, but he was a duly qualified meetway, belonging to Ponsee village. When a youth shows signs of what spiritualists would call a “rapport” or connection with the spirit world, he has to undergo a sufficiently trying ordeal to test the reality of his powers. A ladder is prepared, the steps of which consist of sword blades, with the sharp edges turned upwards, and this is reared against a platform thickly set with sharp spikes. The barefooted novice ascends this perilous path to fame, and seats himself on the spikes without any apparent inconvenience; he then descends by the same ladder, and if, after having been carefully examined, he is pronounced free from any trace of injury, he is thenceforward accepted as a true diviner. Sala improved the occasion by warning Sladen that a powerful combination had been formed to oppose our advance, and that many evil reports had been circulated, but concluded by saying that a liberal expenditure of silver would remove many, if not all, obstacles. The practical application of this was made next morning. When all was ready for a start, the tsawbwa would not appear: Sladen paid him a visit, and was informed that six hundred rupees must be paid nominally as an advance for the mule-men, or else he had better go back. This extortionate demand was reduced after some debate to three hundred, which were paid, and then an additional sum of three hundred rupees was demanded for the carriage of the troublesome and tempting cash-chest. An offer of one rupee per diem each to twenty bearers was refused, and we then decided to divide the cash into parcels of three hundred rupees to be carried by the men of the escort. By this means the liability to continual “squeezes” on the part of the chiefs, or robbery by the porters, was avoided. At length we set out from Ponline, and, after proceeding a mile over an easy road along the high ground, commenced the descent to the gorge, down which, fifteen hundred feet below, the Nampoung flowed into the Tapeng, dividing the hills into two parallel ridges. The descent, at first easy, gradually became steeper, and at length precipitous; the path was cut into zigzags, but as slightly deviating from the straight line as the steepness of the declivity allowed. The weathered and disintegrated surface of metamorphic rock had been worn down by traffic and torrents, so that it often was a deep V shaped groove with but nine or ten inches of footway, and the loaded mules found it difficult to round the abrupt turns in these deep cuttings; huge boulders, stones, and sharp-pointed masses of exposed quartz, made the travelling still more hurtful and dangerous to man and beast. The beds of the streams were filled with fine granite, and in the largest watercourse crossed, a small section was observed, showing a mass of greyish micaceous schist, with large veins of quartz; it was tilted up vertically, and there were distinct indications of bedding in a nearly north and south direction. The Nampoung, whose source lies among the hills to the north-east, is the limit between the districts of Ponline and Ponsee, and was formerly, and must be considered still, the boundary between Burma and the Chinese province of Yunnan, the ruined frontier fort being pointed out on a height commanding the ford. We forded the Nampoung on our ponies, where the stream was a hundred feet wide, and three feet deep. The beasts could scarcely stem the rapid current, which in the event of a fall would have soon swept horse and rider into the foaming Tapeng. The road wound up the face of a precipice, below which the Tapeng rushed down a succession of rapids, with a deafening roar, and a force which nothing could resist, save the prodigious masses of granite which encumbered its bed, while others leaned from the banks as if ready to topple into the raging torrent.

The occasional glimpses of the distant landscape were glorious; on either hand hills towered up into mountains, and range succeeded range, till lost in the blue distance. Our enjoyment of the grandeur of the mountain scenery was, however, somewhat marred by the difficulty of the path, which compelled us frequently to dismount, and let the goat-like ponies scramble as best they could up the deep narrow cuttings. The road contoured the hillside, cut into the face of the rock for some ten feet, presenting every now and again turnings at a sharp angle. On the verge of a precipice of one thousand feet deep, the outer edge gave way under the hind hoofs of Williams’ pony, and he was only saved from destruction by the pony recovering itself with a vigorous effort. Kakhyen roads seem to be purposely designed with a view to reaching the highest points on the given route, and after leaving the river banks, we thus ascended and descended over a succession of lofty spurs abutting on the river from the main range; precipitous ridges, connecting them at right angles, presented tolerably level ground, but with a surface so confined that the traveller looked down into the deep gorges on both sides. Patches of rich loamy soil in the valleys, and on the slopes of the spurs, were cleared for paddy, and in each clearing a small thatched hut raised on poles served as a watch-tower. Near some of the villages perched on heights, limited efforts at terrace cultivation were visible, and in one place a small stream had been diverted for irrigation. Magnificent screw pines and large tree ferns displayed their exquisite foliage, relieved by the blossoms of various flowering trees.

By two o’clock the baggage mules were so jaded that, although we had not made more than eight or ten miles, it became necessary to halt in the jungle. Behind our bivouac towered an enormous shoulder of the mountains, rising four thousand feet above us, and called Lakong. The air was genial and temperate, the thermometer marking sixty-three at 9 P.M., and, with our lamps strung up on bamboos, our followers and servants surrounding the bivouac, we dined and slept comfortably and securely al fresco, while the drivers picketed their mules above and below. Close to our camp were some old Kakhyen burial-places on a rounded hill. Each consisted of a circular trench, thirty-eight feet in diameter, and about two feet deep, surrounding a low mound, containing only one body. The high conical thatched roof which covered newer graves, elsewhere observed, had disappeared, but some of the bamboo supports were still standing. The trenches of some other graves were built round with slabs of stone, the form of the grave and manner of interment reminding one involuntarily of the megalithic burial structures.

Before resuming our march to Ponsee, Sala intimated that caution would be required, as the Ponsee tsawbwa was very indignant at not having received the desired musket. The nats also had signified through the meetway that before starting the guard should fire a volley, and the tsawbwa added a recommendation to use double charges of powder, so that the nats might be doubly pleased. The road lay along tolerably easy ground, as we were now almost on a level with the origin of the main spurs, and by noon of March 6th we had reached the village of Ponsee, three thousand one hundred and eighty-seven feet above the sea-level, and forty-three miles from Bhamô. As the tsawbwa did not appear, and had made no preparation to house our party, the camp was pitched under a clump of bamboos, in a hollow below the village. Ponsee, with its twenty scattered houses, and terraced slopes of cultivated ground, occupied one side of a mountain clothed to its summit, two thousand feet above, with dense jungle and forest, save where clearings betokened the vicinity of other villages far above us.

Our muleteers dispersed themselves and their mules on the upper terrace of a tumulus-shaped knoll overlooking the road, and cultivated on one side in a succession of regular and equidistant terraces. In the afternoon we were visited by a pawmine, accompanied by his wife and several female relatives, who brought presents of sheroo and vegetables. One of the young ladies was inclined to be merry and communicative, in order to attract attention and secure a present of beads. Although she was a wife, her hair was cut straight across her forehead, and hung down behind in dishevelled locks, uncovered by the head-dress which Kakhyen wives wear. An offer of a puggery to supply the defect was received with a peal of laughter, at which the pawmine seemed startled and scandalised, and he reproved his fair cousin in a way that caused her to shrink into abashed silence. During the evening the dangerous temper of the Kakhyen was shown by an unprovoked attack made by one of the Ponsee tsawbwa’s followers upon a Burmese servant, but Sala promptly interfered to protect our man, and declared that he would resent an insult offered to any of our people as if offered to himself. Thus, as in other matters, he so far showed himself honest, though his constant demands for money began to make the leader think his friendship might be too dearly purchased.