CHAPTER FOUR

OPERATION SEALION

Operation Sealion was the invasion planned to take Hitler triumphantly into London. However, it was the invasion that never was. Why was this, why did Hitler not invade Britain; especially after Dunkirk?

To understand Hitler’s dilemma it is necessary to go back to the collapse of the French. Even by his own optimistic standards, Hitler had been taken by surprise at the swift fall of France that left Great Britain as his only major Western European enemy.

When France fell in June 1940 Britain was at her most vulnerable and a successful invasion at that point would have ended the war on German terms. Yet, Germany could not capitalise on its amazing good fortune. No contingency plans had been prepared for such an eventuality; and even if they had existed, the Kriegsmarine was totally inadequate for Sealion.

The reasons for Germany's lack of naval readiness to engage the British fleet were entirely political. Hitler never envisioned a long-term war with Britain, much less an invasion. He considered German mastery of the continent to be central to world domination and expected the ‘nation of shopkeepers’ to be sensible and come to terms. Therefore, since Hitler's strategic aims lay on the continent the Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe received top priority. The navy was merely an ancillary service.

Perhaps there was some merit in this as the Blitzkrieg into Poland then the total collapse of France in just six weeks stunned the world. In June 1940 all that stood between the seemingly invincible Wehrmacht and Nazi domination was the English Channel plus some badly shaken British troops recently evacuated from the continent. The shattered remnants of the British army regrouped and frantically prepared, as best they could, to repel an amphibious assault. Britain once more found herself facing a powerful Continental enemy just as she had experienced back in the days of Philip of Spain and of course Napoleon.

On those occasions Britain had resisted invasion by retaining mastery of the Channel. Sea power proved to be the first line of defence, but in 1940 that now needed to be reinforced from the air. The Royal Navy had learned from Norway and France that Sea power was useless if control of the skies wasn't possible. Theoretically, Operation Sealion appeared simple and Britain should have been an easy target. After all, no anti-invasion plans had been prepared. British pre-war defence relied, as did the French on the Maginot Line. Events, however, overtook the Allies. The Wehrmacht had achieved astounding success since the attack on Poland and the Luftwaffe had proved to be a formidable force. However, due to the heavy naval losses suffered in the Norwegian campaign, Hitler’s operational fleet at the time of Sealion had been reduced to one pocket battleship, four cruisers and a dozen destroyers.

Germany had lost about half its surface navy in the Norwegian campaign, and would have been incapable of keeping the Home Fleet out of the Channel. In effect the British had a 10:1 superiority over the Germans. However, the Royal Navy could not bring this enormous advantage to bear as most of the fleet was engaged in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean, but, as noted, the superiority of the Royal Navy was now challenged by the Luftwaffe. British sea power was no longer the primary issue. It was airpower, and to achieve air superiority the Luftwaffe would have to neutralise the RAF. Only then could British sea power be contained long enough for German ground forces to be ferried across the Channel.

This was the general situation in the summer of 1940. But, how serious was the threat of invasion? Politically, the Führer would have preferred to come to an understanding with Great Britain. He admired the British for the way they had built their Empire and wished to negotiate a peace deal. He was quite convinced that after the defeats in Norway and particularly after the disaster at Dunkirk, Britain would sue for peace, and he offered what many considered at the time to be very generous peace terms. Hitler reasoned that a British defeat in 1940 would bring about the disintegration of her Empire and German blood would be shed accomplishing what would only benefit Japan and the United States.

Hitler broadcast his peace offer on 19th July, but Churchill treated this contemptuously, stating Britain would never sue for peace and proceeded to rally public support for his defiant stance. An irate Hitler retaliated; Britain, despite her hopeless situation, and still showing no willingness to come to terms, would be invaded and subjugated. Hitler announced that Britain was to be eliminated as a base for future operations against Germany and approved Operation Sealion. Other than a draft no detailed plans had been prepared.

The British army stationed in Britain at this time consisted of twenty six divisions, teweve of which had only recently been formed and were not fully trained or equipped. The remaining 14 divisions had lost a vast amount of military hardware in France, thus necessitating obsolete armaments to be stripped from military museums. Under the cash and carry programme Britain was able to purchase half a million rifles and 900 artillery pieces from the US. By September 1940, twenty nine divisions, including two Canadian were equipped and available for national defence.

The Royal Air Force had mobilised the last of its reserves and Spitfire production had accelerated. Lord Beaverbrook, the minister responsible for aircraft production appealed to the public to donate scrap metal to build fighters, resulting in mountains of iron and aluminium that mostly could never be transformed into Spitfires or Hurricanes. However, in terms of morale boosting, it was a runaway success.

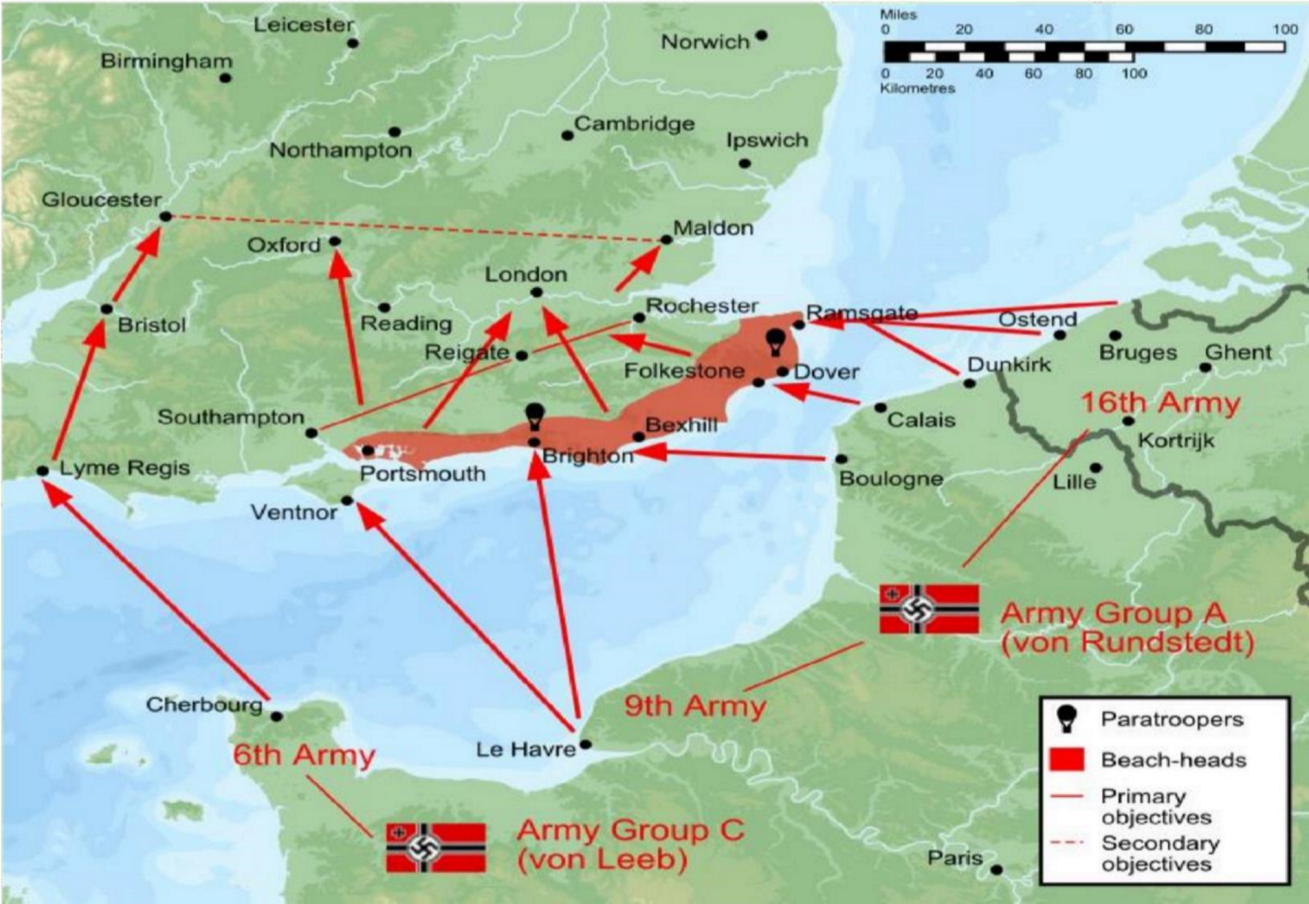

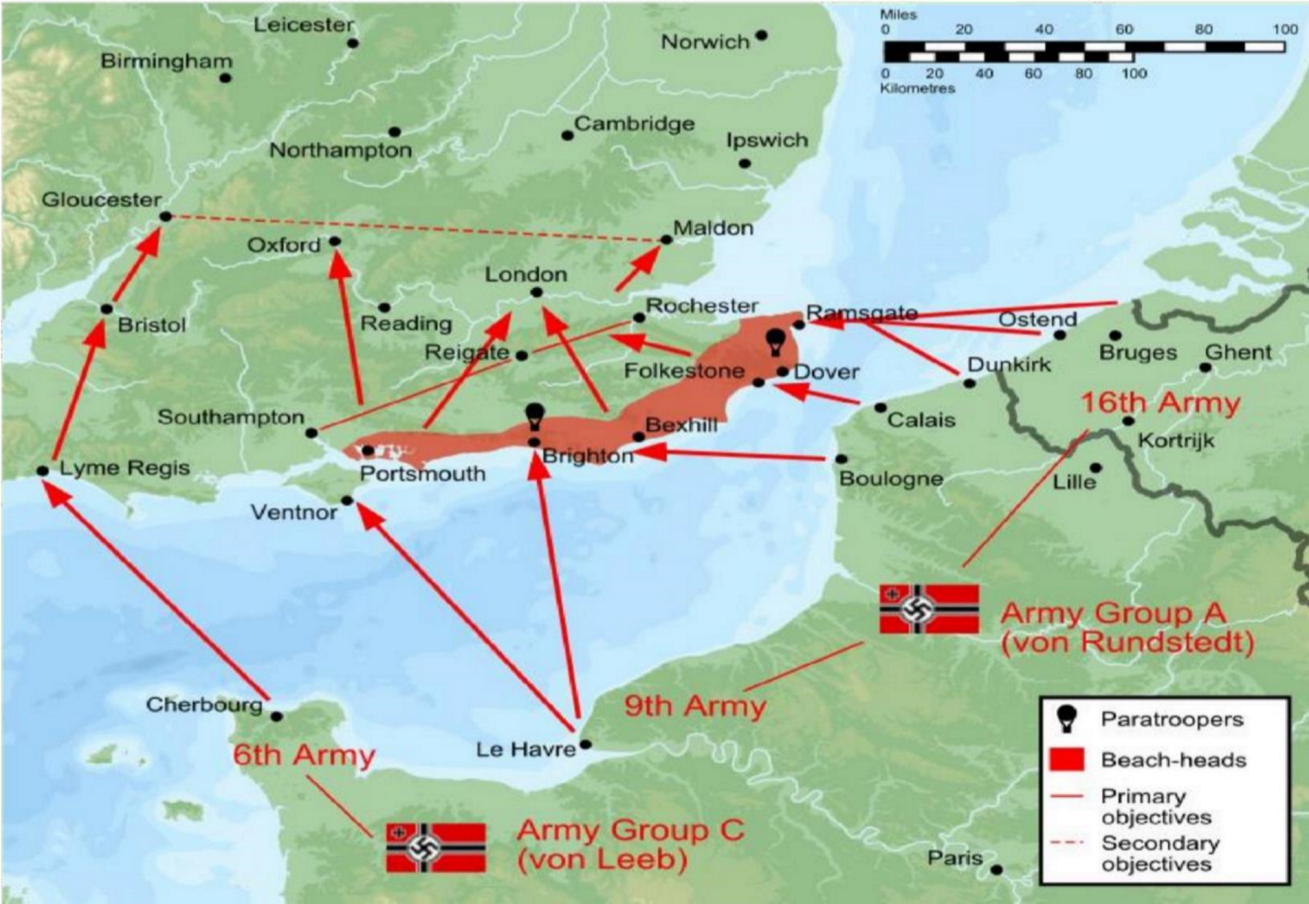

By this time the German Army staff had submitted an invasion plan that would transport forty one divisions across the Channel. Grand Admiral Raeder, who was not a supporter of Operation Sealion rejected this as impracticable and told Hitler of the difficulty in obtaining landing craft suitable to carry invasion troops. He recommended a limited crossing restricted to the Dover area as the German navy could never provide adequate protection over a wide front. Raeder had a far more realistic view of the difficulties involved in Sealion. He considered that the war would be conducted far more successfully by focusing on the Mediterranean and repeatedly warned Hitler of the dangers associated with a landing in Britain. Particularly when faced by an enemy committed to fight. On the assumption that a beachhead could be established on British soil, Raeder stated there was a danger that the Royal Navy would cut off supplies to German troops, isolate them and force their capitulation.

In 1940, a German infantry division required 100 tons of supplies per day and a Panzer division consumed 300 tons. To move nine divisions and sustain them for the first ten days before the second wave was scheduled to land would strain German resources to the limit. In addition to an under strength Navy and inadequate planning, German inter-service rivalries also emerged; especially when the Army saw Operation Sealion as nothing more than a large river crossing in which the ‘Luftwaffe would do the work of artillery’. The army preferred a broad front to split enemy forces, but the navy wanted a narrow front to facilitate protection of the invasion force. Amphibious combined operations require close cooperation between the various branches and the Germans simply did not have this.

On the last day of July Hitler held a meeting at the Berghof. Raeder detailed why he believed the army plan was untenable and argued for a postponement of the invasion until 1941. All three branches of the German military reiterated the problems associated with an invasion. It would require;

1) Control of the Channel

2) Control of the skies,

3) Good weather and,

4) Destruction of Coastal defences.

The result was a compromise. The invasion force was reduced to twenty seven divisions to provide von Rundstedt with a sufficiently wide front to break out and encircle London. Other groups would head towards Gloucester and Bristol and a feint landing on the Norfolk coast was planned to draw off British reserves. Addressing his service chiefs, Hitler made it clear that he recognised the plan had its dangers; especially those identified by Raeder. But he was keen to press Britain into submission so that he could turn his full attention on his real enemy; Russia.

Hitler therefore, wanted operation Sealion to be over by mid-September. Raeder however, claimed the invasion could only start in mid-September providing Göring's Luftwaffe defeated the RAF. As no German battle fleet existed to give off- shore bombardment, long range coastal batteries with ranges of between 40 and 50 kilometres would have to be positioned around the Calais area. Combined with massive Stuka attacks, they were planned to neutralise British coastal defences and prevent the Royal Navy from attacking German troop transports.

The army would immediately capture a port in order to land the Panzers. Air supremacy and the early introduction of armour were thus critical to achieve victory. Hitler rejected requests to cancel; if granted, this would have undermined the invasion as a political threat. The build-up for invasion had to continue and Britain had to be kept under military pressure.

It was decided that the Luftwaffe should tighten the screw by clearing the channel of British warships and the skies over southeast England of British aircraft. To establish command of the Straits of Dover from mid-July the Luftwaffe stepped up the military pressure by attacking the Channel ports and shipping. By the end of July the Royal Navy had to pull all its larger warships out of the channel because of the threat from German aircraft. All seemed to be going to plan; this mounting military pressure and the prospect of invasion were intended to break British spirits and render Operation Sealion unnecessary.

Certainly, neither the threat of imminent invasion nor offers of an 'honourable' peace had done the trick. It appeared that Germany would actually have to execute one of the most difficult military operations imaginable; an invasion, launched across at least 35 km’s of sea culminating in a landing on a fortified and desperately defended coast line. It was immediately clear that this could not even be attempted until the Royal Navy; still one of the most formidable fighting forces in the world had been either destroyed or diverted and the Royal Air Force eliminated.

This resulted in a decisive aerial battle of attrition that became immortalised as the Battle of Britain, and it officially opened on 13th August 1940, “Eagle Day”. It was one of the decisive battles of the war. Air Chief Marshall Sir Hugh Dowding, a master tactician and immensely more capable than Göring, did a first class job in resisting the demand to fling Britain’s last reserves of fighter squadrons into the Battle of France, thus preserving the fighter force that met the German attempt to gain air control over Britain and the Channel. At the time, the Luftwaffe had 600 fighters available. RAF Fighter Command had 670. Britain was actually out-producing Germany in fighter planes, and the proportions were steadily moving in Britain's favour.

At first German attacks were concentrated on the RAF airfields, and almost succeeded; the government issued codeword ‘Cromwell’, to indicate that an invasion was imminent. Church bells rang as a call to arms for the Home Guard. Across the Channel the final preparations for Operation Sealion were concentrated around their embarkation points. The 2 500 transports, consisting of barges, tugs, and light craft massed in the invasion ports came under intense attacks from RAF Bomber Command and Coastal Command.

Believing that British resistance would crumble, and that the RAF would be forced to use its remaining reserve squadrons, Göring intensified the attacks and his losses mounted. These losses were shared between the fighters and bombers; whereas RAF Fighter Command, being constantly in action, bore the brunt and were soon reduced to less than one thousand pilots, who were rapidly reaching a state of physical and mental exhaustion.

However, a dramatic event intervened; Hitler had forbidden terror bombing on civilians but when a German formation got lost and jettisoned their bombs over London, Churchill ordered a reprisal raid on Berlin. Göring ordered counter raids on London thus diverting the Luftwaffe from its original purpose; that is the destruction of the RAF. This caused Operation Sealion to be postponed until 27th September, the last day for favourable tides. After that date Channel conditions would be too risky. The decision to switch objectives from British fighter bases to mass raids on London and other cities cost Germany the battle. Hitler postponed the invasion ‘until further notice’ and ordered the dispersal of the invasion craft. Göring had failed to smash the RAF; proving that the Luftwaffe was clearly not invincible.

During the Battle of Britain, several paramount elements favoured the RAF. First was the defence radar network that although incomplete was the most technically advanced in the world. The work rate of the Hurricanes and Spitfires would have been fruitless but for this effective system of underground control centres and telephone cables, which on Dowding's initiative had been devised and built before the war. It enabled fighter planes to take off in time to avoid being attacked on the ground and directed the fighter planes by radio to intercept and often surprise the enemy.

The RAF also inflicted heavy casualties on the previously all-conquering Stuka’s, proving them to be most vulnerable and they were withdrawn from the battle. The British early warning system foretold any German attacks, and with the help of the code breakers of Bletchley Park, had broken the Ultra code used by the Luftwaffe. By mid-September the RAF had more pilots available than the Luftwaffe. Fighter Command had gained the upper hand and although Britain’s cities were heavily bombed, by mid-October the Battle of Britain was over.

Another key element that gave Britain a massive tactical advantage was that a British pilot who survived being shot down could quickly be returned to operational status, whereas a German pilot who survived was removed from the battle and became a prisoner of war.

Hitler committed a major strategic error by allowing Göring to assume leadership in the Battle of Britain. The Reichsmarshall proved flawed in his judgment by switching air attacks from fighter airfields to London and other cities. Above all, he failed to concentrate on knocking out radar stations.

The plan for an invasion of Britain was from the start a great risk. An unsuccessful landing would nullify all the German achievements thus far obtained and it was acknowledged that the lack of German naval and air superiority would have caused catastrophic harassment to any invasion. Hitler decided that the invasion would be executed only if there were no other ways of forcing Britain to her knees and since such circumstances were never gained, the invasion was postponed indefinitely. Hitler diverted the German war machine to Operation Barbarossa, and was to see, as did Napoleon his great armies annihilated in the bitter Russian winter climate.

In the meantime, Hitler focused on an economic war with Britain and pursued the aim of defeating Britain in three different ways:

-

A combined air and sea attack against British trade and industry;

-

Air bombardment, intended to demoralise the population,

-

With the aid of his allies he would attack British positions in the Mediterranean; such as Gibraltar, Malta and the Suez Canal.

In adopting the Mediterranean strategy, Hitler quite unwittingly, began the geographical dissipation of the Wehrmacht, which in the end would prove fatal. Franco demanded too high a price for helping him take Gibraltar, and Petain was reluctant to assist in North Africa. Only Mussolini was willing, and he was an unpredictable ally.

The plan for Operation Sealion is perhaps the most flawed in the history of modern warfare. Strategic planning and preparation was woefully inadequate and would have left the German Army paralysed; its tanks standing useless without fuel and its army crippled by the lack of resources.

An explanation as to why Sealion was considered to be a huge bluff by Hitler: The German navy was in no real position to wage amphibious warfare and had no ready-made vessels suitable for landing over open beaches. Each service worked separately without a joint staff, resulting in army and navy planners soon developing conflicting ideas.

When France collapsed, in June 1940, the German staff had not even considered, never mind studied, the possibility of an invasion of Britain. Troops had received no training for seaborne and landing operations, and nothing had been done about the means of getting troops across the Channel. The Royal Navy had countless smaller craft, including sloops, minesweepers, converted trawlers and similar craft. These would have been of little value against warships. However, against the Rhine barges forming the main invasion transport force, they would have been effective.

Even if the Germans had won the Battle of Britain, a successful landing would have been a long shot. Assuming that they did establish air superiority and a beachhead in Southern England, there was still a considerable British force waiting for them, and a quick powerful counter-attack supported by the Home Fleet was a real possibility. If the Germans did repulse this counter-attack and have a strong invading force with tanks and air cover, they now would have to capture London; one of the five largest cities in the world. It would have been held at all costs and taken months to capture, even if surrounded and besieged. Another factor is that the heavy war industries of the Midlands and Scotland would still be in British hands. Their production capacity would allow the British to continue to be supplied during any fighting. Therefore, the Germans would have to capture all of the country. Unlike France, the British would not surrender after a portion of the country was captured. The Germans would have to fight through the large urban areas of major cities such as Birmingham and Liverpool at a terrible cost.

The British could also call on huge reinforcements from India, Canada, Australia and South Africa to match the Germans in men deployed in battle. It has been suggested that an invasion immediately after Dunkirk would have produced a German success, as it would have been easier at that time. It is true that the British Army was less able to offer resistance in July than it was by September. But the difficulty facing the Germans was not beating the British Army; it was getting across the Channel in the face of the RN and the RAF.

In July the German forces had not gathered any transports and only had the capacity to lift less than one infantry division. It should be remembered that Britain had retained 24 fighter squadrons as Home Reserve. These squadrons were rested, maintained and ready. The Luftwaffe, on the other hand, had flown many sorties in the French campaign and needed time to recover. Plus the British Radar chain was undamaged, as was the command and control structure. So the RAF was at peak efficiency in July whilst the Luftwaffe had tired crews and aircraft in need of repair.

Operation Sealion can only be described as a blueprint for a German disaster. The first steps to prepare for an invasion were taken only after the French capitulated and no definite date could be fixed. It all depended on the time required to provide the shipping, and alter them to carry tanks, and to train the troops in embarkation and disembarkation. The German invasion of Crete a year later provides an indication of what may have occurred at Sealion. Reinforcement and supply by sea proved impossible even though the Luftwaffe had absolute air superiority. The Royal Navy intercepted and utterly destroyed the flotilla of small boats crossing from Greece. Although they eventually prevailed, German paratroops and transport aircraft were decimated in the process.

One can imagine the slaughter had the RN and RAF run through the barges loaded with men and equipment during the proposed Sealion crossing. Planning an invasion and assembling a fleet in a few weeks was clearly impractical, but timing was an essential part of the game of bluff that Hitler was playing. Also, the extraordinary timing that he imposed, suggests the political rather than the military nature of the invasion. Germany did not have the industrial capacity to build specially designed landing craft for amphibious operations.

The first instruction to begin planning for Sealion was issued 84 days before the proposed invasion date. In 1944 D-Day had been in the planning phase for two years. The parallels between Operation Sealion and Operation Overlord are striking. In every category Allied preparation for Overlord was far superior to German efforts in Sealion. On D-Day the largest amphibious force ever assembled prepared to breach Hitler's vaunted Atlantic Wall to liberate Europe. Getting soldiers into landing craft and onto the proper beach on time is no mean feat. Plus coordinating Naval Gunfire and Close Air Support adds another degree of difficulty. The multitude of organisational and logistic considerations involved in amphibious operations is staggering. Every function in the overall plan is interdependent, relying upon precise execution for success. Most importantly, every aspect of the landing plan was reinforced with realistic training. When the Allied forces went into combat on 6th June 1944 they were physically and mentally well prepared.

Even if Fighter Command had been wiped out, RAF Bomber Command was largely intact and would have attacked the beachheads day and night. The Germans lacked the means to keep the beachheads adequately supplied and had no plans for artificial harbours or pipelines across the Channel, both of which played a crucial part in supplying Allied operations in Normandy.

As their intelligence was very poor, the Germans had little knowledge as to which beaches were the most heavily defended or the proximity of British reserves to the beaches. British counter-intelligence had already captured or ‘turned in’ all German agents operating in Britain, which limited Germany to aerial photographs. The overall concept and execution of Overlord was a masterpiece of strategic planning made possible by the enormous capacity of Allied industry. In Normandy, the Allies had complete naval and air superiority. They also had a host of special equipment, coupled with hard-won experience, and a considerable level of support from the local population. The creation of an ‘Atlantic Wall' stretching from Spain to Norway, covering some 4 500 kilometres was one of the largest construction projects in human history, but, as Frederick the Great noted, ‘He, who defends everything, defends nothing’

Another reason why Sealion is considered a huge bluff is that at the meeting Hitler called to discuss various options, the Luftwaffe did not attend; even though it was recognised that the Luftwaffe was essential to win air supremacy and to keep the RN out of the way. The concept for getting 9 divisions across the Channel was to block the west of the Channel with U-Boats, and the east of the Channel with mines and torpedo boats. The proposed time between the first landing and the second wave of reinforcements and supplies would be 10 days. Thus 9 attacking divisions, without any heavy equipment, would be expected to hold out against 29 defending divisions for this period. o get the first wave across, the Germans gathered 170 cargo ships, 1 300 barges, and 500 tugs. The barges were mainly those designed for use on the Rhine; wash from a fast-moving destroyer would swamp and sink them.

Thus, if Royal Navy Destroyers could get close to the invasion fleet they could actually sink the lot without firing a shot. These same barges were also underpowered for open water operations, and required towing by a tug at a speed of 3 knots, in the Channel, which has tides of 5 knots. German troops would be wallowing for a minimum of 12 hours in an open boat, and then be expected to carry out a fiercely opposed amphibious landing. If this seems to be a nightmare scenario, and a recipe for disaster, it is nothing compared to other elements. The most ridiculous of which was the plan for manoeuvring the invasion barges on the landing beaches. This huge mass of towed barges was to advance in line at night coordinated by loud hailer's.

Only one training exercise was conducted off Boulogne. It was in good weather and good visibility, with no navigation hazards or enemy defences to contend with. Of 50 vessels committed, less than half managed to land their troops at H Hour. One tug lost its tow; one barge overturned when too many soldiers crowded on one side and several barges landed broad-side and were unable to lower their ramps. The results of the fifty-barge exercise did not bode well for an assault on Britain.

Then there was the Irish Question. Operation Green was the German code name for the decoy invasion of Ireland, planned in conjunction with Operation Sealion in 1940. Barges were to be sent towards the south coast of Ireland to give the impression of a wide scale sea invasion of the British Isles. German agents were parachuted into Ireland to make contact with the IRA and to initiate a bombing campaign throughout Ireland to destabilise the country.

Once the I.R.A. bombing campaign got underway, German paratroops would be parachuted into zones to sever communication lines and capture RAF airfields. The Luftwaffe would then be able to strike at targets in Scotland and the west coast of England and strangle Britain’s lifeline in the Atlantic. The agents, however, reported back to Germany that the I.R.A. were ‘unreliable’ and ‘undisciplined’ and would take months to train. The operation was finally scrapped when Sealion was placed on indefinite hold; and the German agents were later captured.

As noted previously each service vied with the other for Hitler's favour. As a result, command relationships between the services were often strained and operations suffered accordingly. Just to make matters worse, no engineers or equipment were included in the first wave to deal with obstacles. The invaders would have to cross rivers and canals more than 20 metres wide and had no means of getting across. Then there is the question of life jackets. Thousands had been provided, but, despite all the best efforts of the planners, there were only sufficient for the first wave. According to the plan, these life jackets would be brought back again by the boats needed for the second wave. The problem was that these life jackets were worn beneath the combat pack. The troops were expected, while under fire, to first take off their pack, then their life jacket, and then don the combat pack again, and only then start doing something about those rather inconsiderate British shooting at them. One wonders what the veterans of Omaha beach would say about the viability of this. Not that it would have been of the slightest use because no one had been made responsible for collecting the life jackets and return them to the boats. The life jackets would simply have piled up on the beach.

Then there was the matter of artificial fog. A serious conflict arose between the Army and the Navy regarding the use of artificial fog. The Army wanted it for protection on the open beaches. The Navy was opposed to its use for the reason that the landings were difficult enough without making it impossible to see anything. Inevitably, a compromise solution was found; it was ruled that the Army would decide whether or not to deploy artificial fog, but that it was the responsibility of the Navy to actually deploy it.

The Luftwaffe was expected to do all of the following:

-

Act as artillery for the landing forces

-

Keep the Royal Navy out of the Channel

-

Win total air superiority

-

Prevent British Army reinforcements from getting to the beachhead by bombing railway lines

-

Make mass attacks on London to force the population to flee the city and choke the surrounding roads.

With a limited range, the fighters would have a huge number of areas to protect. Meanwhile the RAF would be presented with many targets, such as barges, landing beaches and transport aircraft. If the Germans are flying fighter cover over the barges; then these fighters are not escorting German bombers, leaving them unprotected against RAF fighters. In this case, the Luftwaffe would be ineffective at keeping the Royal Navy at bay. The British came up with a far superior defensive plan such as pre-emptive attacks on staging areas, interdiction at sea and all-out assaults at the landing points. In a short period the Army refitted the survivors of Dunkirk, organised a Home Guard, created beach defences, and set up mobile reserves.

Hitler’s far reaching decision to stop the Panzer’s before they could deliver the coup de grace to the BEF at Dunkirk has never been satisfactorily explained. Perhaps he did not seek the outright submission of Britain. However, what is for certain is that he genuinely believed that in the end, Britain would come to terms; thereby, facilitating a rapid victory in the east that would shatter Britain’s last hope of containing Germany. An impatient Hitler repeated Napoleon’s mistake by trying to crush Russia before he had settled with Britain, resulting in a nightmarish war on two fronts.

Hitler failed to learn the lessons of Napoleon. He fully expected Britain to be content with a simple balance between a land power and a sea power. But as had been her foreign policy for 500 years, Britain would only accept a balance of power on the Continent itself. Hence, Churchill’s announcement to Stalin that German hegemony in Europe was as dangerous to the Soviet Union as it was to Great Britain and urged that both countries should agree on the re-establishment of the European balance of power. Although Churchill often spoke of restoring freedom to the nations of Europe, it was the balance of power that really concerned him. Something Hitler failed to grasp as basic British traditional foreign policy.

The invasion of Britain was the obvious strategic direction for Germany to pursue, but the planning was half-hearted when compared to that for the German invasion of the Soviet Union. Planning and preparation for both possibilities continued into the summer of 1941, but it was obvious by then that the campaign against the Soviets was taking shape while that against the UK was not.