CHAPTER TWELVE

THE BATTLE OF LEYTE GULF

The largest naval battle in history, the Battle of Leyte Gulf off the Philippines was another step in the U.S. advance toward the Japanese home islands. All available Japanese forces were thrown into the area but the separate units failed to unite, resulting in several actions scattered over a wide area. All four Japanese light carriers were sunk, as were three battleships. Leyte Gulf also marked the first use of a desperate new tactic: The kamikaze carrying a bomb deliberately crashed on its deck.

When American forces in the Philippines capitulated in May 1942, General MacArthur's pledge to return seemed at best a valiant dream. MacArthur himself acknowledged; "The road back, looked long and difficult”. But the general's determination became his driving force, and within two and a half years the Americans were ready to return.

By mid-1944, a succession of staggering reverses had brought Japan to the brink of defeat. The great Japanese military force that had carved a mighty empire across East Asia and vast stretches of the western Pacific had suffered heavy losses in men, ships and planes. Allied offensives pressed relentlessly against a crumbling Japanese strategic perimeter and gathered increasing strength for the final crushing blows. The swift, powerful carrier and battleship flotillas of Admiral Chester Nimitz struck far and wide, devastating Japanese defences and seizing island after vital island in an unremitting drive toward the heart of Japan's empire. A second major enemy force, the armies of General Douglas MacArthur, with powerful air and naval support, had fought its difficult way up the island axis of the south-west Pacific in a punishing assault that threatened Japanese lines of communication to the vital East Indies. And complementing these twin offensives were the strangling blows of American submarines and long-range bombers, striking repeatedly at Japanese shipping and rear area bases. Indeed, American victories in the Marianas had brought the Japanese home islands themselves within range of U.S. heavy bombers.

Japan was well aware that an American seizure of the Philippines would effectively end the flow of precious oil from the southern empire. The Philippines were also a key link in the island chain which provided a natural security perimeter behind which merchant ships passed to and from the homeland. US submarines were constantly disrupting the movement of supplies along the chain, but the close proximity of each link's naval and air bases made these attacks risky and costly.

In July, therefore, Japanese strategic planners took another look at the deteriorating situation. On the 24th, Imperial General Headquarters issued a comprehensive plan of defence to hold the Philippines, Formosa, the Ryukyus (Okinawa), the four main Japanese islands, and the Kuriles. Codenamed Sho (Victory). The Sho plans required close timing and coordination. Skill in execution, no less than good fortune, would determine their outcome. And on their success or failure rested the fate of Japan. It involved a complicated scheme of manoeuvre to counter any Allied offensive with massive naval, air and land attacks in a climactic `decisive battle' to determine the outcome of the war. Given the weakened state of Japanese combat units, however, none could be committed until the precise target of the enemy offensive was determined. Then, combined naval and air forces would attack at the last possible moment to destroy transports and covering warships. In this manoeuvre, the once proud Japanese carrier forces, now all but stripped of first-line aircraft, would be reduced to a decoy role, to draw off the American battle fleet and leave the rest of the invasion force to Japanese naval gunfire and land-based air strikes. Any enemy troops who subsequently managed to get ashore could then be easily handled by the Japanese army.

Meanwhile, the Americans were working out details for the liberation of the Philippines. By-passing and isolating Japanese strong-points in the Pacific had proved to be a highly successful American tactic and this policy dictated that the Philippines also should be by-passed. However, the decision to liberate this large group of heavily fortified islands was largely political. It was deemed essential to American prestige not to by-pass the Philippine people. The combined strength of the United States Army and Navy was therefore to be committed to a single course of action.

MacArthur's drive toward the Philippine Islands, which had brought his Southwest Pacific Area forces westward along the coast of New Guinea, was the southern prong of an enormous pincers movement. The northern prong, involving the Pacific Ocean Areas forces under Admiral Chester Nimitz, had thrust through Japanese-held island groups - the Solomons, Gilberts, Marshalls and Marianas - and crippled the air arm of the Japanese Navy. By September 1944, both great forces were poised some 300 miles from the southernmost Philippine island, Mindanao.

The invasion now about to take place had long been the subject of debate. MacArthur and Nimitz, coequal commanders who each took orders only from the U.S. Joint Chiefs in Washington, had cooperated effectively in their converging drives toward the Philippines, but they had disagreed on the next phase of the campaign. Nimitz did not share MacArthur's emotional commitment to liberating the Philippines. He was interested in the islands mainly as stepping-stones to another objective: Formosa, 200 miles north of the Philippines and roughly 600 miles south of Japan itself. Formosa's capture would also cut Japan off from its southern sources of raw materials and permit the Allies to land on the China coast around Hong Kong, where they would be able to build air bases from which to bomb Japan.

MacArthur rebutted that if the Philippines were recaptured first, the invasion of Formosa would be easier - and perhaps unnecessary. He even proposed to liberate Luzon, the largest Philippine island. In an effort to settle the debate, President Franklin D. Roosevelt journeyed to Hawaii. There MacArthur presented his views with his usual eloquence. He argued that Luzon could be taken more cheaply than Formosa and that it would serve much the same strategic purpose. He insisted that American honour and prestige in the Far East demanded that the U.S. liberate its own territory, and that it would be easier to do that than to invade Formosa because the Filipinos' loyalty and the help of the guerrillas would make it unnecessary for the U.S. to tie up large occupation forces. The Luzon-Formosa issue remained unresolved.

The debate was finally settled quite by accident during the second week of September 1944. At that time Admiral William ‘Bull’ Halsey, commander of the Third Fleet under Nimitz, launched a series of air raids on the Philippines to test their defensive strength. Vice Admiral Mitscher, commander of the Third Fleet's Task Force 38, executed the attacks, and planes from his fast carriers, battered Japanese airfields in the central Philippines. Returning pilots reported that they had destroyed 478 planes, most of them on the ground, and had sunk 59 ships. There was little opposition.

To Admiral Halsey this was "unbelievable and fantastic”, and he jumped to the conclusion that the Japanese position in the Philippines was "a hollow shell with weak defences and skimpy facilities”. He became convinced that the whole invasion timetable could he accelerated and he proposed a speedup. Nimitz generally approved Halsey's suggestion, and on 13th September, passed it on to Washington. The Leyte invasion was moved up by two months to 20th October 1944. MacArthur clinched the matter by promising the Joint Chiefs that under the new schedule he would be ready to invade Luzon before the end of the year. On 3rd October the Joint Chiefs made it official: the invasion of Luzon would follow the campaign for Leyte.

Even as the Japanese prepared to implement Sho, a major American offensive was about to begin. As stated previously, after months of debate over targets and objectives, the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff approved plans for the invasion of the Philippines. On Halsey's recommendation, plans for the seizure of Mindanao and other intermediate objectives were dropped in favour of a direct assault on Leyte on 20th October 1944. Unbeknownst to the Americans, after the fall of the Marianas, Imperial General Headquarters had designed the Sho plan. This radical scheme, divided Japan's Pacific sphere into four huge defence zones, each with its own plan for handling an Allied attack. Every local commander was forbidden to commit his troops or planes until Tokyo activated the plan for his zone. Thus the failure of Japanese aircraft to effectively oppose Halsey's carrier-plane attacks was nothing more than a reflection of the commanders' obedience to their standing Sho orders. In fact, Imperial Headquarters had decided that the Sho, defence plan for the Philippines would not be triggered until the Americans invaded Luzon, which the Japanese considered the most important island in the sprawling archipelago.

The Japanese leaders believed that they would be able to correctly anticipate America's next invasion sufficiently far in advance. However, Admiral Halsey played havoc with the Japanese plans as TF-38 destroyed the aircraft defences piecemeal. This placed the Sho plans in trouble from the very beginning. Firstly, the majority of Japanese air power throughout the chain was knocked out before the battle even began. Secondly, they were not able to forecast the invasion location until after it was too late. Thirdly, the Sho plan to respond quickly was delayed until additional aircraft could be flown down from Japan. Once the Japanese were convinced that the invasion of Leyte Gulf was for real, they set an elaborate plan in motion which would involve all of their available combat ships. The stage was now set for the world's largest naval engagement - the Battle for Leyte Gulf.

MacArthur would be initially operating without land-based air cover. Until he could establish airfields on Leyte itself, he would be dependent on the carrier support of Halsey's Third Fleet and on the closer protection of Vice-Admiral Thomas Kinkaid's Seventh Fleet, which had the immediate mission of transporting and supplying the invasion force. Halsey's armada, with nearly 100 modern warships and more than 1 000 planes, was one of the strongest battle fleets ever assembled. But it was not under MacArthur's command, and Halsey retained the option of withdrawing his support of the beachhead should a more lucrative mission present itself. The Seventh Fleet, to be sure, was 'MacArthur's Navy' as it was popularly called - but it was organized primarily for transport, bombardment and assault missions, and its air element, mounted on small, slow, unarmoured escort carriers, had only a fraction of the strength of Halsey's. In this divided command arrangement - of which the Japanese were unaware lay the best hopes for the success of the Sho operation.

The Japanese were also victims of a confused and divided command structure, which denied them the central control so necessary for execution of the complex Sho plan. This was especially true in the Philippines, where no single commander existed to coordinate the multi-faceted defence. General Yamashita (of Singapore fame) commanded the Fourteenth Area Army and Lieut. General Tominaga commanded the Fourth Air Army. Each were separate, independent units, responsible to Field Marshal Count Terauchi. He, in turn, had the entire army area command from the Philippines to Burma, and thus could devote only part of his time to coordinating operations in the Philippines. Naval forces were entirely separate. Practically all were a part of Admiral Toyoda's Combined Fleet. The major combat units, each an independent element responsible only to Toyoda, were these: Vice Admiral Kurita's 1st Striking Force of battleships, cruisers and destroyers, located near Singapore so as to be assured a ready source of fuel; the carriers of Vice-Admiral Ozawa's Main Body, in the Inland Sea of Japan; and Vice-Admiral Shima's 2nd Striking Force, consisting of some cruisers and destroyers, also based in northern waters. Under separate commands, but also reporting to Toyoda, were naval air units in the Philippines and elsewhere. The Combined Fleet commander would thus have to control and coordinate all naval forces in the Sho operation, while Field-Marshal Terauchi had a similar responsibility for army units, and neither had a link with the other except through the separate Army and Navy Sections of Imperial General Headquarters.

For the Japanese Navy, the Battle for Leyte Gulf would be the last real chance to survive - and the last real chance to stem the American tide. Toyoda's fleet was divided into three forces. The most powerful of these was Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita's Centre Force, which included the mammoth battleships Musashi and Yamato. Kurita, approaching from Singapore via Borneo, planned to steam eastward through the middle of the Philippine archipelago, transit San Bernardino Strait between Luzon and Samar and emerge into the open sea. Then he would come roaring down from the north upon the American invasion forces in Leyte Gulf at dawn on 25th October.

At the same time, Vice Admiral Shoji Nishimura's Southern Force was to enter Leyte Gulf from the south through Surigao Strait with a fleet of 7 older, slower warships. Nishimura's force was the second arm of the pincers movement that Toyoda hoped would wipe out the American invasion fleet. Behind Nishimura, serving as a sort of rear guard for his ships, would come Vice Admiral Kiyohide Shima with 7 cruisers and destroyers.

The third segment of the divided fleet, the Northern Force, was weak but indispensable to Toyoda's hopes. It consisted of 4 aircraft carriers, which had put out from Japan in the company of 2 battleships, and 11 light cruisers and destroyers. This force, under the command of Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, had sailed from Japanese home waters with only 116 planes aboard. But Ozawa needed no planes to fulfil his mission; he was to be a decoy and his only function was to lure the Third Fleet carriers north, away from Leyte Gulf, so that Kurita, Nishimura and Shima could strike unopposed.

The Japanese revamped their naval tactics to make the most of their great strength in battleships and cruisers. The pride of the fleet were the 68 000 ton Yamato and Musashi; they were the largest battleships afloat and possessed the biggest guns as well - 18 inches. The Sho-1 plan called for these mighty vessels and their accompanying ships, backed up by land-based planes, to sink the American invasion fleet.

Almost immediately, this disjointed command arrangement contributed to a major Japanese blunder. Halsey's carriers undertook heavy pre-invasion strikes against Japanese bases. After some hesitation, Toyoda independently directed implementation of the Sho plan by naval air units, in the mistaken belief that the invasion had actually begun. Terauchi, however, did nothing - although it probably would have mattered little if he had. Toyoda's premature commitment of his air units resulted in extremely heavy Japanese losses: in less than a week Halsey's flyers destroyed more than 600 Japanese naval aircraft, at small cost to themselves, crippling Toyoda's air arm. It was now impossible to carry out the vital initial air phase of the Sho plan, to defend Combined Fleet surface units against American air strikes, or to reinforce the relatively weak Japanese army air groups in the Philippines to protect Yamashita's troops.

This error only served to compound the confusion among Japanese commanders, so that when the invasion of Leyte actually did begin a few days later there was a crippling delay in implementing Sho. American forces began preliminary landings to the east of Leyte on 17th October, following up with minesweeping and clearing operations the next day. But not until the evening of the 18th, after considerable confusion among the various Japanese commanders involved, did the Army and Navy Sections of Imperial General Headquarters order the start of the Sho operation. And not for an additional 37 hours did Toyoda actually issue execution orders to the Combined Fleet. Thus, when MacArthur's forces landed on Leyte itself on the morning of 20th October, Japanese fleet units were still far away from Philippine waters. On top of the earlier Japanese air losses, this delay frustrated the Sho objective of catching the American invaders in the midst of their landing operations.

During the American strikes, Fukudome had sent several squadrons of torpedo bombers to attack the ships of the Third Fleet at night. Although most of these planes were shot down too, they succeeded in damaging the cruisers Canberra and Houston so badly that the ships had to be towed away to safety. The inexperienced Japanese pilots - apparently mistaking the flames of their downed planes for burning ships - came back with such enthusiastic claims of success that even cynical Japanese commanders thought that Halsey's force had been severely crippled. The alleged victory was soon inflated even more.

Japanese newspapers headlined a ‘Second Pearl Harbor’, and the Emperor ordered celebrations. The national euphoria affected the judgment of Imperial Headquarters. When an American invasion fleet appeared in Leyte Gulf a few days later, the new confidence of the Tokyo planners prompted them to question their earlier decision to fight the decisive battle on Luzon. General Yamashita saw no reason to shift the plan from Luzon, where most of his troops stood ready in prepared defences. But his superior, Field Marshal Terauchi, argued that Sho should go into effect whenever the first Philippine island was invaded. He won over Imperial Headquarters to his view; Tokyo believed that at least half of the Third Fleet had been sunk and that the Americans were recklessly attempting an invasion of Leyte with reduced forces. Presumably, the weakened U.S. carrier-plane force would be unable to prevent a massive movement of Japanese troops and supplies to Leyte. The decision was made: the climactic battle would be fought on Leyte. The order was carried by liaison officers who did not arrive in Manila until 20th October. By that time, the invasion of Leyte was under way.

To retake the island, the separate commands of General MacArthur and Admiral Nimitz had converged on Leyte’s east coast. Nimitz's Third Fleet, under Halsey, contained Mitscher's force of 16 fast carriers, plus 6 fast new battleships and 81 cruisers and destroyers. Almost everything else came under MacArthur's control, adding up to a staggering command: Lieut. General Walter Krueger's Sixth Army, with 6 divisions totalling two hundred thousand men; Lieut. General George Kenney’s Fifth Air Force based on five Pacific islands; and ‘MacArthur's Navy’, Vice Admiral Thomas Kinkaid's U.S. Seventh Fleet, which was to support the beachhead with its small escort carriers and slow old battleships. All these units arrived unopposed, and Krueger's assault forces met with only light resistance as they went ashore on the morning of 20th October. The Americans assumed that enemy warships were closing in around them, but they had no inkling of what the Japanese battle plan might be.

However, the Japanese plan began to unravel almost at once. On the morning of 23rd October, Kurita's approaching Centre Force was spotted by two American submarines, and they radioed a warning to the Third Fleet, giving Halsey his first news of what the Japanese were up to. Alerted for action, the Third Fleet carriers swung east of the Philippines and dispatched scout planes to search for Kurita's ships. The next morning 24th October, a search plane from the U.S carrier Intrepid found Kurita's Centre Force; another plane from the Enterprise located Nishimura's Southern Force; and a Fifth Air Force patrol bomber observed Shima's Southern Force. With mounting excitement, Admiral Halsey assumed direct tactical command of Mitscher's carrier planes by personally ordering them to attack the big target, Kurita's Centre Force.

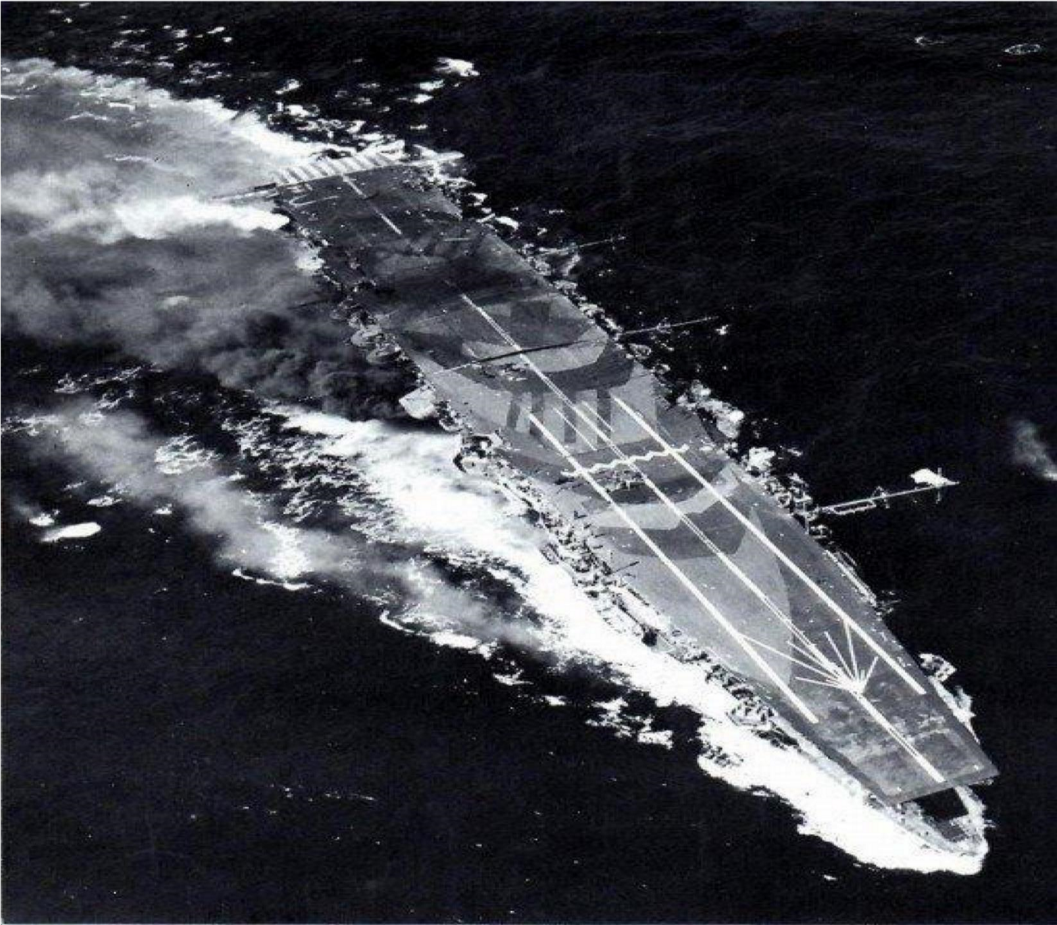

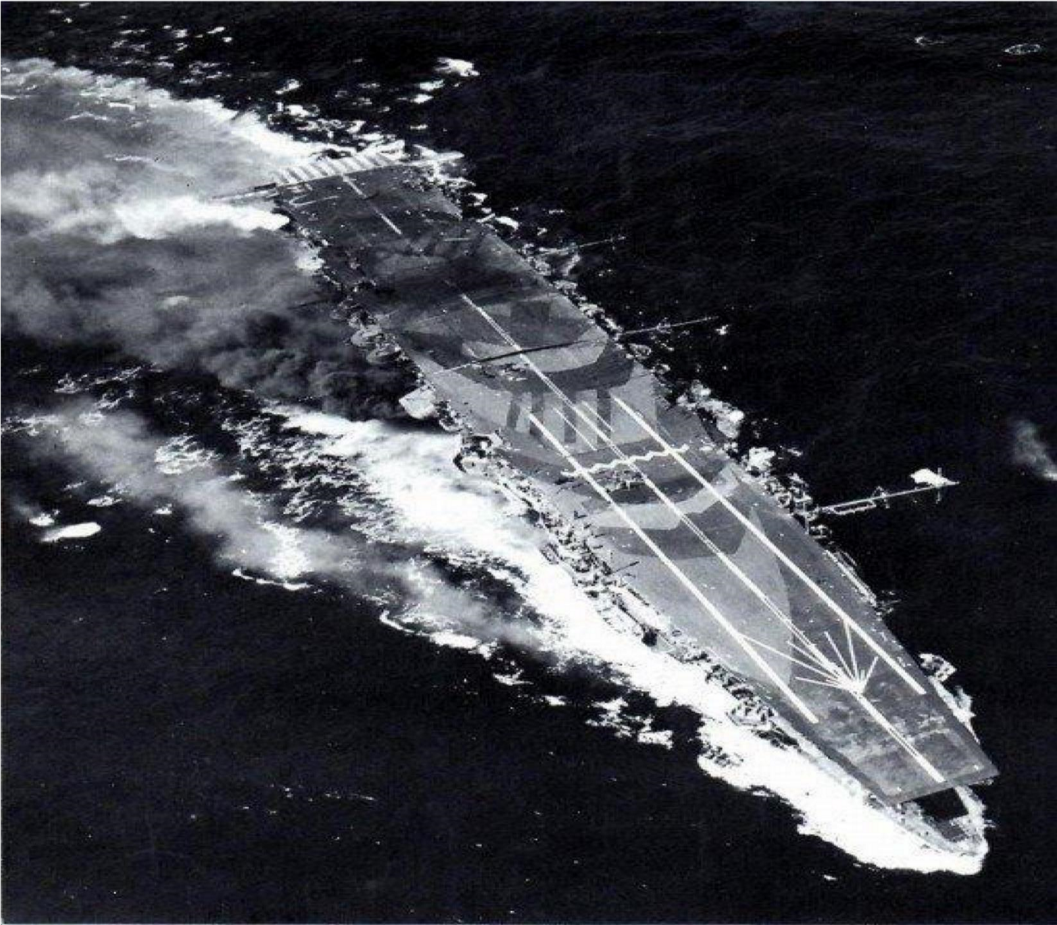

American radar picked up several large groups of Japanese planes headed for the American Third Fleet. These were the remains of Admiral Fukudome's air forces based on Luzon, about 200 planes in all. But the Americans were ready for them. Hellcat fighters destroyed about 70 of the Japanese aircraft and prevented all but one of them from getting near the American ships. However, that one Japanese plane dropped a bomb on the carrier Princeton, turning her into an inferno.

The bomb had penetrated deep within the Princeton, where it exploded, set off secondary blasts, and hurled flaming aviation fuel throughout the ship's interior. Although the blaze seemed manageable at first, the Princeton was already doomed. At around 15 30 hours a great explosion shook the carrier, tearing apart her stern and throwing huge lethal fragments of steel into the midst of the fire-fighters and across the crowded deck of the cruiser Birmingham, which had drawn along-side to assist. With her upper decks covered with killed and wounded, the Birmingham had to pull clear of the stricken carrier in order to take care of her own casualties and repairs. The Princeton, once again fully ablaze, was abandoned. American torpedoes sent the flaming vessel to the bottom, the first fast carrier to go down in two years.

Yet the sinking of the Princeton cost the Japanese dearly. In concentrating all planes in the vicinity on one of Halsey's carrier groups, Fukudome had left Admiral Kurita's Centre Force with practically no air cover. Their assigned role in the Sho plan had been to destroy enemy warships blocking the approach of the Japanese fleet, had not even partially achieved their mission. Nor had army aircraft of General Tominaga's forces been any more successful in their attacks that day on Seventh Fleet units in Leyte Gulf. In a mass attempt to sink the great concentration of invasion shipping there, nearly all of these planes had struck again and again at the landing area throughout the 24th. The repeated assaults had forced American aircraft from the escort carriers to break off their ground support missions in order to protect the anchorage. But Tominaga's flyers had caused little damage to shipping. And nearly seventy Japanese planes - perhaps half the total number of attackers - had fallen victim to Admiral Kinkaid's fighters and anti-aircraft gunners.

Meanwhile, Admiral Halsey had been inflicting sharp punishment on the two Japanese surface forces steaming towards Leyte Gulf. An initial attack by about a score of Third Fleet pilots on Nishimura's ships caused only light damage. But Kurita, who received the brunt of the air strike, was less fortunate. From just before 10 30 hours until the middle of the afternoon, five separate blows - a total of well over 250 sorties - staggered his force as it made its way doggedly through the narrow, reef-infested waters of the Sibuyan Sea.

At 15 30 hours, finally, shaken by a number of false submarine alarms, and fearing continued air assaults in the confined waters of the San Bernardino Strait that now lay just before him, Kurita decided to reverse his course for a while. It was not until 17 14 hours, when he felt that the approaching darkness ruled out further American air strikes, that he once again resumed his original course towards the strait. An hour later he received a brief directive from Toyoda that had been despatched to all naval units engaged in Sho: 'All forces will dash to the attack, trusting in divine assistance’! In response, Kurita informed Toyoda that he would 'break into Leyte Gulf and fight to the last man'.

Two of the Third Fleet carrier groups had launched planes for a massive attack on Kurita's powerful force as it came steaming toward San Bernardino Strait. Without fighter protection, Kurita had to rely on his vessels' anti-aircraft firepower. Each battleship carried 120 anti-aircraft guns, each cruiser 90. Kurita also had a unique secret weapon: the huge 18 inch guns aboard his super-battleships, the Musashi and the Yamato, could be elevated to fire at aircraft with a special type of shell known as sanshikidon, each of which would spray 6 000 steel pellets in shotgun style over the sky.

With all antiaircraft guns pointed skyward, Kurita's battle-ships looked like giant porcupines when the American air-planes struck. The first wave of 21 fighters, 12 dive bombers and 12 torpedo bombers from the carriers Intrepid and Cabot flung themselves against a wall of flak at 10 30 hours. Several of the planes were hit, but many got through. The U.S. fighters strafed the decks of the warships and forced the gunners to take cover as the torpedo bombers skimmed in to drop their missiles. One torpedo hit the cruiser Myoko, which lost speed and had to retire. A bomb and a torpedo hit the Musashi, but the great ship was protected by armor plate 16 inches thick, and she just shuddered at the blows and steamed serenely on.

Shortly after noon a second attack wave struck. Hits were scored on Kurita's flagship, the Yamato, and 4 more torpedoes shook the Musashi. Three of those torpedoes struck the Musashi's port bow, where her armor was relatively thin, and the explosion peeled back the outer plates. The jagged rip slowed the ship down, and Kurita ordered the entire fleet to reduce speed to 22 knots so that the Musashi could keep up. Less than an hour later another group of planes, from the Lexington and the Essex, swarmed over the groggy Japanese fleet. The Musashi's damaged bow kept spewing a great geyser of water into the air as the battleship ploughed along, making her plight obvious to all the American fliers, who swooped in for the kill. Four more torpedoes ripped into the Musashi. As her damaged bow sank lower in the water, the battleship began to fall behind the rest of the fleet.

Until early afternoon the captain of the Musashi, Rear Admiral Toshihira lnoguchi, refused to fire his main battery's sanshikidon at the attacking planes. Those special shells could damage a gun's bore and lnoguchi wanted to save his barrels for the 3 220 pound shells he still expected to fire at surface targets in Leyte Gulf the next day. But now he knew all too well that the Musashi was in trouble, and he gave his gunnery officer the go-ahead. The three great turrets - three guns each - swung toward the east and the massive barrels were pointed skyward.

When another wave of American carrier planes appeared in the distance at 14 30 hours, the guns fired with an enormous concussive roar. The men on deck were deafened for a while, and those below felt as though a spread of torpedoes had smashed into the ship's hull. The gunnery officer peered through the smoke and noted with dismay that the planes were still advancing. The oncoming pilots, launched from the Enterprise and the Franklin, noted that the antiaircraft barrage was the heaviest they had encountered in the War. But the Japanese marksmanship was surprisingly poor: the shell bursts always trailed behind the planes. Clearly, the Japanese gunners were aiming not by radar but by sight.

While the Franklin's planes concentrated on the Yamato, the Enterprise attacked the Musashi. To blind the anti-aircraft gunners below, the US pilots attacked from behind the sun. Then, one by one, his 9 Helldivers, each carrying a double load of two 1 000 armour-piercing bombs, nosed over and screamed down at the Musashi. The bomber pilots had never seen such an inviting target; big, steady and slow-moving. They stayed late in their dives, released both bombs and pulled away, climbing out of danger to the north. Then the Enterprise's 8 Avenger torpedo bombers spread out and came in low on each side of the Musashi, aiming for the damaged bow. Just as the last Helldiver released its bombs, the Avengers dropped their torpedoes into the water and swerved away. Wrote one Enterprise officer later; "The big battlewagon was momentarily lost under the towering fountains of near misses and torpedo hits, soaring puffs of white smoke from bomb hits and streaming black smoke from resultant fires. Then the long, dark bow slid out of the cauldron, slowing. Musashi stopped, down by the head, and burning”.

Planes from the Intrepid, Essex and Cabot joined those from the Franklin and Enterprise and swarmed over Kurita's ships at 15 10 hours. Several more torpedoes hit the Musashi, knocking out two of her four propellers and forcing damage control personnel to flood three of her four engine rooms to prevent the ship from capsizing. The captain signalled, "Speed six knots. Damage great. What shall we do”?

Kurita ordered the Musashii to return to base, but she was rapidly taking on water, and her list had increased, forcing her to move in a circle. Later, Kurita ordered: "Musashi run aground at top speed and become a land battery”. Even this ignominious mission was too much for the Musashi. The executive officer shouted, "All crew abandon ship. You're on your own”. The great ship rolled over onto her side, baring her barnacle-encrusted bottom. Water rushed through gaping torpedo holes, Survivors sprinted and scrambled along the ship's bottom, bare feet lacerated and bleeding. Reaching the bow, which now dragged at water level, they stepped into the sea and started swimming. When looking back they saw the Musashi's stern pointing straight up, silhouetted against the setting sun, with several men clinging to it. Then the great ship plunged beneath the sea with loud suction noises and rumblings and underwater explosions. Four hours later destroyers picked up several hundred survivors, but one thousand and twenty three officers and sailors, almost half the Musashi's crew, had perished with the ship.

In addition to sinking the Musashi and crippling the cruiser Myoko, the day-long attacks had damaged the Yamato and two other battleships. The damaged ships could still fight, but Kurita had to slow down his fleet to prevent them from falling out of formation. The westward turn was noted by Halsey's fliers, and it influenced the admiral's next decision. His pilots reported that 4 of Kurita's battleships had been severely damaged, that 9 cruisers and destroyers had been sunk or heavily damaged, and that the remains of the armada were retreating westward. Halsey assumed that the Centre Force was no longer a threat, and he turned his attention to what he thought was bigger game.

All day his planes had been searching for the carriers he felt sure must be part of this massive Japanese naval operation. Finally, at about 17 30 hours, one spotted the carriers of Admiral Ozawa's Northern Force 300 miles to the north of San Bernardino Strait. Now, Halsey reckoned, he had "all the pieces of the puzzle”

Halsey regarded the Northern Force as the major threat; if its air strength was combined with the other enemy forces, it could jeopardize MacArthur's landing operations in Leyte Gulf. Halsey did not know, of course, that Ozawa's four carriers had only a few planes left on board. Lacking that intelligence, the Third Fleet commander considered three courses of action; he could keep his fleet where it was, in position to guard against attacks by both the Northern and Centre Forces; he could send his carriers af