CHAPTER IV

WELCOME TO THE HOUSE OF MARKE GJONNI—WE HEAR THE VOICE OF AN OREAD—A GUARDIAN SPIRIT OF THE TRAILS.

Concealed by the darkness, we lay back in our wet clothes on the wet rocks and shook with smothered laughter. How Albanian! While Perolli with a hundred honeyed words made excuses for the feebleness of foreign women, already weary with only sixteen miles of mountain climbing. He was still explaining when up the trail came the flare of a torch, and an Albanian boy of perhaps fourteen years appeared, a turban on his head, a rifle on his back, and a silver-hilted knife stuck through his orange sash.

“May you live long!” said he.

“May you live long!” said we.

“How could you?” He meant, “How could you get here?”

“Slowly, slowly, little by little,” we replied.

“Are you a man?” said Perolli.

“I am a man of Pultit, of the village of Plani, of the house of Marke Gjonni,” said the boy. “In our house there is always a welcome for the stranger. The door of the house of Marke Gjonni is open to you.”

“Glory to your lips and to your feet,” said Perolli, and to us in English: “His father has sent him to ask us to come to his house. What do you think?”

“Is anyone going to think?” we cried. “There’ll be a fire, won’t there?”

We followed the boy up the mountain side, our lungs sobbing and our feet slipping on the trail dimly lighted by the torch, and so steep that the palms of our hands were bruised by climbing it. Out of the ceaseless swishing murmur of falling water that had surrounded us all day one note rose above the rest; flying spray was like a mist on our faces; we were following the edge of a waterfall hidden by the dark. Then the trail turned; we stood on a level ledge; and suddenly all the rifles in the world seemed to go off not ten feet away.

“It’s all right!” Perolli’s shout came up from the darkness beneath our feet. “They’re only welcoming you!” But I have never felt so defenseless, so nakedly exposed to sudden death, as I did standing there, clutching Frances and Alex, while sharp flashes darted out of the blackness and deafening explosions contended with more deafening echoes. All the household of Marke Gjonni stood on the trail, every man firing his rifle until it was empty. Then a woman appeared with a torch, her beautiful face and two heavy braids of hair painted on the darkness like a Rembrandt, if Rembrandt had ever used a model from ancient Greece, and we made our way through a jumble of greetings (“May you live long! May you live long!” we repeated), and up a flight of stone steps along the side of a blank stone wall, and through a low, arched stone doorway.

The stone-walled room was large—as large as the house itself—and low ceilinged, and filled with shadows. Near the farther end, on the stone floor, a bonfire burned in a ring of ashes. In the corner near the door several goats and two kids and two sheep stopped their browsing on a heap of dry-leaved branches, and looked at us with large eyes shining in the torchlight. Five or six women came out of the shadows to greet us, and behind us the men were coming in, reloading their rifles, hanging them on pegs, closing and bolting the heavy wooden door.

Rexh and our two gendarmes were already busy unrolling the packs, spreading our blankets over heaps of dried grass on the other side of the fire. In a moment we were sitting comfortably on them, extending wet feet toward the flames, while one of our hosts put a fresh armful of brush on the coals, another hacked slivers of pitch pine from a great knot of it and set them blazing in a small wrought-iron basket that hung from the ceiling, and another, with hollowed-out wooden bowls of coffee, of sugar, and of water around him, began making Turkish coffee in a tiny, long-handled iron bowl set in the hot ashes.

“We’re going to have a night in a native house, after all,” said I, happily, and added, starting, “What’s that?” A long, thin, curiously unearthly sound—hardly a wail, though that is the dearest word I have for it—was abroad in the night that surrounded the stone house. Even the shadows seemed to crouch a little nearer the fire, hearing it, and when it ceased the splashing of the waterfall was louder in the stillness. Then the man with the coffee pot pushed it farther among the coals, and with the little grating noise the movement of the household recovered and went on.

“Are you a man?” said our host, courteously, turning his clear dark eyes on Perolli, and Perolli, silencing me with a glance, folded his arms more comfortably around his drawn-up knees and began the proper conversation of a guest.

By degrees the house of Marke Gjonni grew clearer to our eyes; they became accustomed to the firelight and the shadows and saw the guns hanging on the wall, the browsing goats that, with a little tinkling of bells, worried and tore at the dried green leaves on the oak branches heaped for them, the outlines of a painted wooden chest filled with corn meal, at which a woman worked making a loaf of bread on a flat board. One of the men raked out some coals and set in them a round flat iron pan on legs—the cross and the sun circle were wrought on its bottom. In the midst of the flames he laid its cover to heat. Soon the woman came with the bread, a loaf two feet across and two inches thick, and deftly slid it from the board into the pan, which it exactly fitted; one of the children put the cover over it and buried all in hot ashes.

There were ten or twelve children—little girls half naked, with serious, beautiful faces and long-lashed brown eyes; small boys dignified in little long tight trousers of white wool beautifully braided in black, short fringed black jackets, and colored sashes and turbans like those of their fathers. Two cradles stood near the fire, covered tightly over high footboards and headboards with heavy blankets; presently a woman partly uncovered one and, kneeling, offered her breast to the tiny baby tied down in it. Only the baby’s puckered little face showed; arms and legs tightly bound, it lay motionless and uncomplaining, and when it was fed the mother kissed it tenderly and covered it again, carefully smoothing the many folds of thick wool and tucking the ends tightly beneath the cradle.

Meantime Cheremi was taking off our shoes and stockings and bathing our feet in cold water brought by one of the women. This was proper, since when guests arrive the member of the family nearest to them by ties of blood or affection acts as their servant, and Cheremi, being an Albanian who knew us, was judged to stand in that position. By the time we had drawn on dry woolen stockings from our packs the first cup of coffee was ready. To the boiling water in the tiny pot the coffee maker added two spoonfuls of the powdered coffee, two of sugar, stirred the mixture till it foamed, and poured it into a handleless little cup which he offered Perolli. But Perolli indicated me, and without the slightest revelation of his surprise the host changed his gesture.

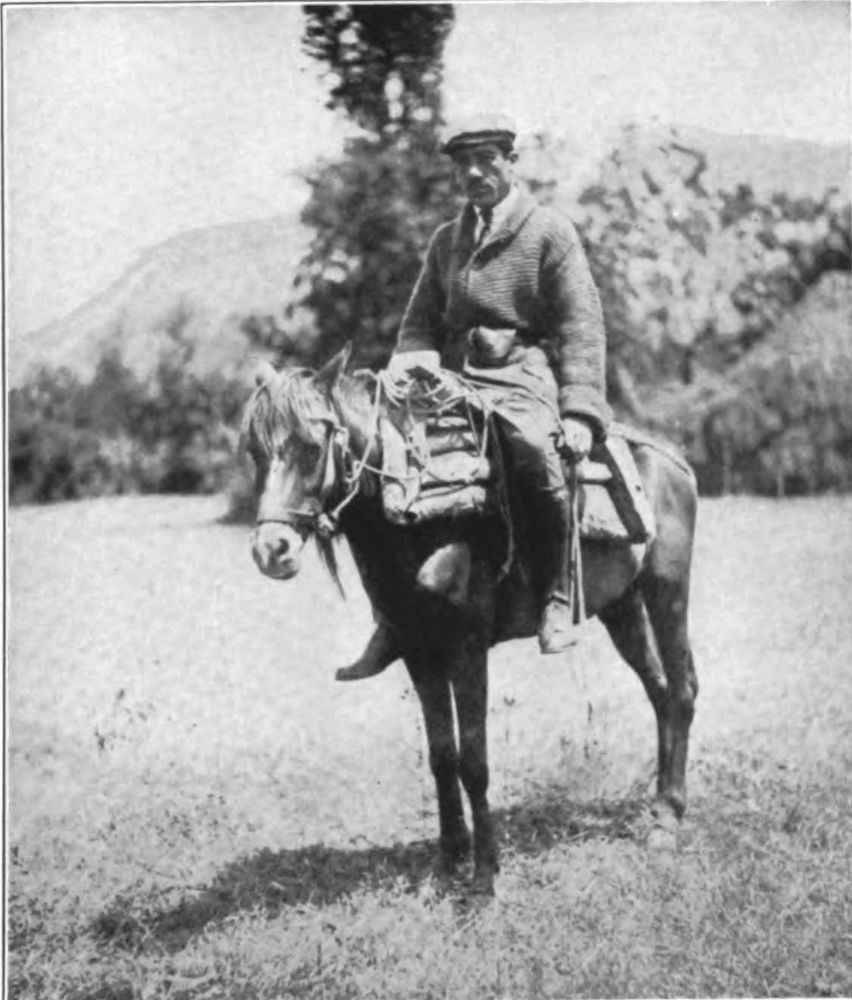

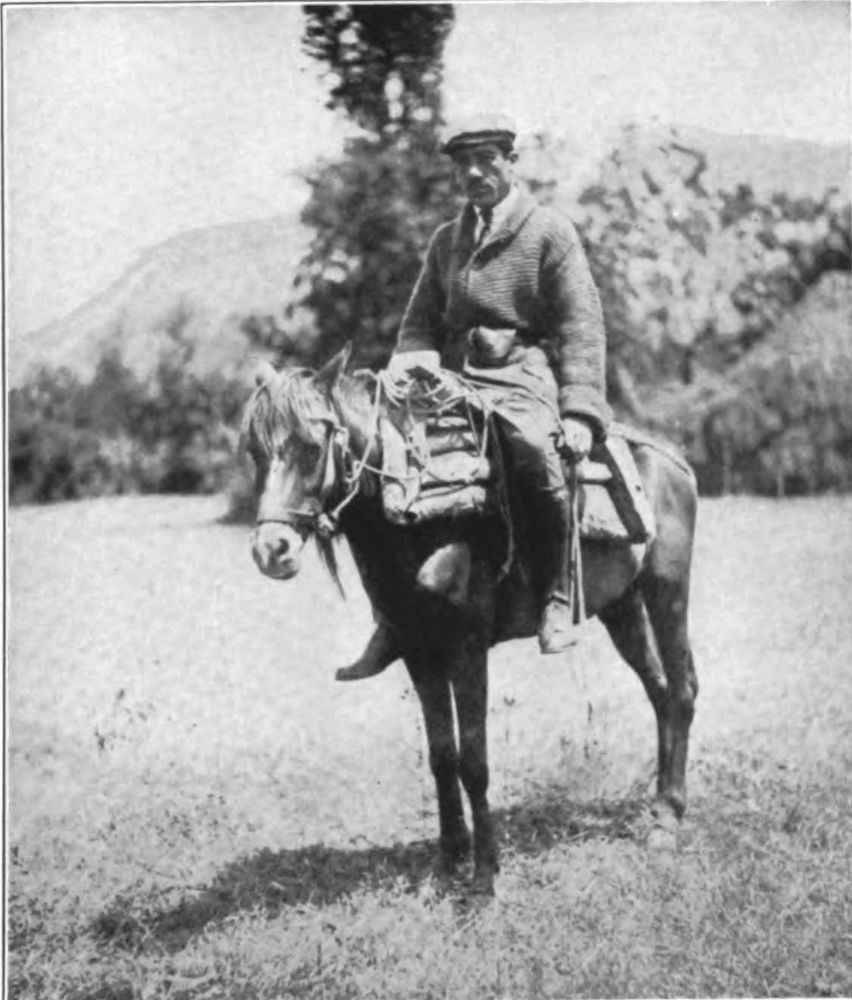

RROK PEROLLI

“Beauty and good to you,” said I, in Albanian, prompted by Perolli, and when I had drunk the thimbleful, “Good trails!” said I, handing back the cup. For this is the manner in which one drinks coffee. Do not make the mistake, when next you are in the Albanian mountains, of saying the same things when you are offered rakejia. For rakejia there is a quite different form of courtesies. And as soon as the coffee cup, rinsed and refilled with freshly made coffee, has been given to each guest in turn, you will be offered rakejia.

Alex and Frances and I looked at one another, but we drained the large goblet of colorless liquid fire in turn, without a word of protest. It might have been the water that it looked like, so far as it affected our minds or tongues, for I continue to ascribe to the fire warmth and the blessed sensation of resting after those trails the sense of contentment that filled us all.

“Strange,” I said, for I still dimly remembered another way of life, as though, perhaps, I had sometime dreamed it, “chimneys that don’t draw make so much smoke in a room, yet here there is no chimney and a large fire, and we don’t notice the smoke.” And, leaning back on the piled blankets, I gazed up at the pale-blue clouds of it, rising beyond the firelight into a velvety darkness overhead. But I really felt that I had always lived thus, shut off by stone walls from the mountains and the night, ringed around by friendly familiar faces, smelling the delicious odor of corn bread baking and hearing the tinkling bells of goats.

“Where is America?” said our hosts, and: “How large are your tribes? Do they have villages like ours, and mountains? Do you raise corn? How many donkey loads do you raise to a field, and what is your method of cultivating the soil? Have you stone ditches for carrying water from the rivers to the fields?” Rousing ourselves, we tried to give them in words a picture of our cities; we told of horses made of iron, fed by coal, snorting black clouds of smoke and racing at great speeds for long distances on roads made of iron; and I told of the irrigation systems of California’s valleys, and Oregon’s; of orchards plowed by steel-shod plows; of great machines as large as houses, cutting grain on the plains of Kansas; of mountain streams like Albanian mountain streams, which we harness as one might harness a donkey, and how their invisible strength is carried unseen on wires for many, many long hours—as far as an Albanian could walk in two days—and used to turn wheels far away.

Resting comfortably on their heels around the fire, they listened as one would listen to a traveler from Mars, the men opening silver tobacco boxes and deftly rolling cigarettes for us, the women spinning, the children—each given its space in the circle—propping little chins on beautiful, delicate hands and listening wide eyed. The questions they asked—and the elders were as courteous to the children’s curiosity as the children were to theirs—were keen and intelligent, but when it came to explaining electricity I was as helpless as they and could answer only with vague indications of some strange unknown force which we use without understanding it.

A woman, barefooted, barearmed, graceful as a sculptor’s hope of a statue, lifted the cover from the baking-pan, crossed herself, made the sign of the cross over the hot loaf, and took it up. Stooping, with the smoking golden disk between her hands, she stopped, suddenly struck motionless. The long, strange cry came again through the darkness, like a voice of the wind and the mountains and the night.

“Look here, Perolli,” said I, my stretched nerves unexpectedly relaxing into the kind of anger that is part of fear, “what is that? Don’t be an idiot! Tell me!”

“It is an ora, if you must know,” said Perolli, and he looked at me defiantly, as though he expected me to laugh.

“An ora!” said Frances, sitting up. The strange, unearthly call came again, very far away this time; we strained our ears to hear it. Then silence and the roaring of the river. The turbaned men in the circle of firelight, who had understood the word, nodded.

“Holy crickets! Rose Lane, we’re actually hearing an oread!” Frances exclaimed. And Alex said: “Oh no! Undoubtedly there is some natural explanation.”

“How do you know there isn’t what you call a natural explanation for an oread?” Frances demanded, and the wild notion crossed my mind that if Perolli had not been with fellow sharers of the blessings of Western civilization he would have been crossing himself instead of lighting another cigarette. Little Rexh, in his red fez, spoke earnestly: “Do not believe there are no ora or devils in these mountains, Mrs. Lane. There are very many of them.”

“Of course,” said I, and I do not know how much I believed it and how much I assumed that I did, in order to encourage our hosts to talk. “Do you often see ora in this village?” I said across the fire to the many intelligent, watching eyes, and Rexh picked up our words and turned them into Albanian or English as we talked.

“We do not see the ora,” said a tall man with many heavy silver chains around his neck. “Do you see the ora in your country?”

“I do not think they live in the West,” said I. “I think that they are very old, like the Albanians, and, like you, do not leave their mountains. This is the first time I have ever been where they live, and I should like to meet one.” But I doubt if I should have said that if I had been outside those solid stone walls.

“Perhaps you will hear them talking when you go through the Wood of the Ora,” said a woman whose three-year-old daughter was going to sleep in her lap.

“Very few people have seen them,” said the coffee maker, licking a cigarette and placing his left hand on his heart as he offered it to me. I fitted it into my cigarette holder; he lifted a burning twig from the fire and lighted it. “Now my father was accompanied by an ora all his life, but he was the only one who saw it, and he told no one about it until just before he died.”

“Did he ever talk with her?”

“No, but she always walked before him on every safe trail. He was sixteen when he first saw her; he was watching the goats in the mountains. She appeared before him, standing on the trail. He said that he knew at once that she was not of our kind, because she was so beautiful. She was about twelve years old, wearing clothing not like ours, but of a white and shining material—my father said that it was like mist and it was like silk and it was like fire, but he could not say what it was like. Her hair was golden. She stood on the trail and with her hand she made a sign to him to stop, and he stopped, and they looked at each other for a long time. Then he spoke to her, but she did not answer. She was not there. And my father went on, and found on the trail he would have taken a great rock that had just fallen, and he knew that the ora had saved his life.

“He came home, and said nothing. The next morning when he went out with the goats the ora was waiting outside the door, and she went before him all that day. Always after that, whenever he left the house, she went before him on the trails.

“My father was a strong man and very wise; he married and had many children; he fought the Turks and the Austrians and the Serbs and the Italians. He had a good life. But he never went anywhere unless the ora went before him. In the morning when he left the house, if she was not there he returned and sat by the fire that day. Often on the trails he was with many people, but none but him ever saw the ora. She remained always the same, always the size of a twelve-year-old child, always very beautiful, shining white and with golden hair.

“When she turned aside on the trail, my father turned also, and the people did as he did, though he did not say why. My father was known as a very wise man. Many times he saved the lives of many people by following the ora.”

Several of the older men in the intently listening circle shook their heads, as though they remembered this, and when I asked them with my eyes they said, “Po! Po!” which means, “Yes.”

“When my father was sixty-five years old, strong and healthy, one day the ora did not come. She did not come the next day, nor the next, nor the next, for many days. Then my father knew that she would not come again and that it was his time to die. So he arranged all his affairs and died. Just before he died he told us about the ora; he told us so that we would know why he was making ready for death, and it was because his ora had left him.”