CHAPTER V

THE UNEARTHLY MARRIAGE OF THE MAN OF IPEK—FIRST NIGHT IN A NATIVE ALBANIAN HOUSE.

There was a moment of contemplative silence. Beyond the circle of firelight the goats still tore and worried the dried leaves from the oak branches. A woman came leisurely forward and put an iron pan on the coals. When it was hot she brought scraps of pork and laid them in it. Rexh, the little Mohammedan, turned his head so that he should not smell that unclean meat. Frances said to Perolli, in a ravenous voice, “How much longer will it be before we can eat?”

He looked at her reprovingly. “In Albania it is not polite to care about food.”

“But it’s past midnight and we’ve had nothing to eat since noon!” Frances mourned.

“Slowly, slowly, little by little,” said Perolli, soothingly. For myself, I curled more comfortably among the blankets, too contented to ask for anything at all. It was as though I had returned to a place that I knew long ago and found myself at home there. I had forgotten that these people are living still in the childhood of the Aryan race and that I am the daughter of a century that is, to them, in the far and unknown future. Twenty-five centuries had vanished, for me, as though they had never been.

“That lady ora was no doubt betrothed to one of her own people,” said a man who had not previously spoken. “Now in my lost country of Ipek—may the Serbs who are murdering her feel our teeth in their throats!—I know a man who was married to an ora.”

A woman, barefooted, wearing a skirt of heavy black and white wool, a wide, silver-studded leather belt and a blouse of sheer white, her two thick black braids of hair falling from beneath a crimson headkerchief almost to her knees, came out of the shadows beyond the fire and lowered from her shoulder a beautifully shaped wooden jar of water. She held it braced against her hip, and, stooping, poured a thin stream over our outstretched hands. We laved them, the water sinking into the ashes around the fire, and another woman handed us each a towel of hand-woven red-and-white-plaided linen. Then we sat expectantly, but only a wooden bowl of cheese was set on the floor before us.

It was goat’s-milk cheese, rather like the cottage cheese of home, except that it was hard, cut in cubes, and of an acrid, sourish flavor. We each took a piece, nibbled it.

“Oh, Perolli, can’t you tell them we’re starving? It’s almost one o’clock in the morning!” cried Frances, pathetically.

“Be patient,” said Perolli. “How many times must I say that it isn’t polite in Albania to be so greedy?”

“But it’s eleven hours since any of us had a bite!” Frances protested. “Don’t tell me Cheremi and our other men aren’t starving.”

“Albanians don’t care so much about food,” said Perolli. “I’m not hungry.” He lit another cigarette, and, seeing the circle of politely incurious but keen eyes fixed on us, I said, “Tell them that we are very much interested in the story about the ora, and that we want to hear about the man who married one.” And I surreptitiously prodded Alex, who, sitting bolt upright with her eyes open, was obviously asleep with fatigue.

The man who had spoken of that unearthly marriage rolled and licked a cigarette, offered it to Alex with his hand on his heart, rolled himself another, lighted both with a blazing twig, settled comfortably on his heels, and began.

“This man was my friend, well known to me and to all the families of Ipek. A strong man, a good fighter, and respected by all. But his life was not complete, for the girl his father had chosen for him had died, and he was not married. There were many girls he might have had, girls of Montenegro and even of Shala and Shoshi and Kossova, but he said that he did not wish to marry. He came to his thirty-seventh year and was not married.

“One night he was sitting alone in his house, making a cup of coffee in the ashes of the fire, when the door opened. He looked, and there was a woman who had come out of the darkness. She was no woman of our tribe, nor of any other tribe of man, though she was dressed like our women. My friend looked at her and said to himself that he had never known women could be so beautiful. Men could be as beautiful as that, yes, but not women. And he knew, though he did not know how he knew, that she was not of our kind.

“He said to her, ‘Long life to you!’ and she replied, ‘And to you long life!’ She came and sat by his fire, and he gave her the cup of coffee one gives a guest. She drank it and returned the cup to him, saying, ‘Good trails to your feet!’ Then they looked at each other for some time without speaking.

“Then she said to him, ‘Am I not beautiful?’ And he said, ‘Yes.’ She said to him, ‘Have you ever seen a woman more beautiful?’ And he said, ‘No.’ And after she had been silent for a long time she said to him, ‘Will you marry me?’ And he said, ‘No.’

“She said to him, ‘Do you think you will find a woman more beautiful than I?’ He looked at her between the eyes and said, ‘I know that I shall never see a woman so beautiful.’ She said, ‘Then will you marry me?’ And he said, ‘No.’

“‘Why will you not marry me?’ she asked, and he said, ‘I do not wish to marry.’ So for a time they sat silent, and then she said, ‘Do not forget me,’ and went away.

“He told me these things, and I said to him, ‘She was an ora.’ He said, ‘Yes, I know.’ I said, ‘Was she a gypsy ora?’ For, as you know, there are two kinds of ora, and if she were a gypsy ora I would have been troubled for my friend. He said, ‘No, she was a lady ora.’ We spoke no more about it.

“Three years went by, to a day, and again it happened that my friend was sitting alone in his house, making a cup of coffee in the ashes of the fire, when again the door opened.”

The man of Ipek stopped speaking, opened his silver tobacco box, and put a pinch of the long, fine, golden tobacco on a cigarette paper. He spread it carefully, twisted it into the cone shape of the Albanian cigarette, glanced at us to see that none of our cigarette holders were empty, and placed the white slender cone between his lips. He lighted it and drew several deliberate puffs. No one spoke. There was the red circle of firelight, the graceful black and white and colored figures huddled close to it, around us the shadows of the house, and beyond them the vast, murmurous blackness of the night and the mountains; the chill and mystery of them seemed to be pressing against the stone walls that kept them out, and the sound of the waterfall was like the sighing breaths of strange, wild things.

“My friend was sitting by his fire, like this, but he was alone. It was the third coming of that day of the year on which the ora had come out of the darkness, and when again the door opened he knew, without turning to see, who it was.

“She came in, and he turned and said, ‘Long life to you!’ Then he saw that with her was a manservant, and that manservant was of her own kind. She said to my friend, ‘And to you long life!’ She sat by the fire, and he gave her coffee, and she drank, and the manservant stood in the shadows behind them.

“‘Have you forgotten me?’ she said, and my friend said, ‘No.’ They looked at each other, and she said, ‘Am I not beautiful?’ And he said, ‘Yes.’ Then she leaned close to him and said, ‘Will you marry me?’ And he said, ‘No.’

“When he said that she rose, and she was more beautiful angry than she had been before. She said: ‘Come with me. My father wishes to see you.’

“He said, ‘What have I to do with your father?’

“She said, ‘Come with me.’

“My friend did not know why he went, or how he went, or where he went. They came to a place in the mountains, but it was a strange place, and strange mountains—my friend could not describe that place. It was a place in our mountains, but such a place as no man had ever seen. There were trees that were alive; it was all my friend could say. There were many souls of trees about him, and they were ora, and among them was their king, who is the king of the ora. He stood before the king of the ora.

“The king looked at him and said, ‘Will you marry my daughter?’ And he said, ‘No.’

“The king said to him:‘My daughter has seen you. My daughter wishes to be your wife. She will be a good wife to you. She will bring you great happiness. She is my daughter, a lady ora.’

“My friend said: ‘I thank you. Your daughter is very beautiful and very good. But I do not wish to marry.’

“The king of the ora said, ‘If you will marry my daughter you will have all the heart desires. I will make you rich in the things that men call riches in the Land of the Eagle.’

“My friend said: ‘I am a poor man. I am not a bey of the south, of the land of the Toshk, but I am a Gheg, a man of the mountains. All that I need I earn with my hands, and that is enough. I do not wish to marry.’

“Then the king of the ora rose, and he was not angry, but he was very terrible. He said, ‘Marry my daughter.’

“And my friend married his lady daughter.”

The man of Ipek seemed to think that the story was ended. But I, who had been scribbling all this down in my notebook, hidden in the shadow of Rexh, as Perolli translated it to me paragraph by paragraph, did not agree with him at all. “What happened?” I wanted to know.

“Nothing happened. His family came into the empty house and he was gone, leaving his gun on the wall and the empty coffee cup by the dead ashes of the fire. They were very much afraid. My friend had not told any man but me about the visit of the ora three years before, and I said nothing. Some days went over the tops of the mountains, and no one knew where he had gone. Then he came back, and brought with him his wife, the ora.”

The rest I got by questions.

“No one could see her except my friend,” said the man of Ipek. “No one but he ever saw her. He built himself a beautiful house; there were rugs in it, and tables of carved wood, and bowls of copper and silver—all things that are beautiful. Cigarette holders of amber and silver with jeweled bowls, and sashes and turbans of silk, and cushions of silk, and beautiful jars for bringing water from the springs. All kinds of rich and beautiful things, and always great quantities of delicate and rich foods. The men of Ipek remember that house well.

“Yes, my friend is dead now. He lived in happiness with his wife for twenty years, and they had children whom he loved. But only he could see them, for to others they were invisible, like his wife. I have been in his house many times when she was there, but I never saw her. Others say they have seen strange things in that house; they have seen things moved by hands they could not see. But I never saw that. Only I know that my friend was happy with his wife and children. She was a lady ora, and kept his house well. The gypsy ora are dirty folk, but the lady ora love cleanliness and order. Everyone respected my friend and his lady wife. Whenever he entered a village, all guns were fired in his honor, for men said, ‘The man who married a lady ora is coming into the village.’ Oh, it was all very well known in Ipek, among the people of my tribe who are now slaves to the cursed Serbs.

“When he died, no doubt she went back to her own people, taking their children with her. His family came to take back his house, and they found all manner of beautiful things, but no money. No money anywhere.”

“What do you think of it?” I said to Frances. “Do you believe——Great Scott! Of course it isn’t true! I don’t know what’s wrong with my mind. Men don’t marry tree spirits. It’s absurd.”

But, frankly, my conviction was that of the man who whistles cheerfully while passing a graveyard at night, because, of course, he does not believe in ghosts.

“There’s some natural explanation,” said Alex. “The man went away for some reason—perhaps he actually had found some of the treasure they say is buried in these mountains—and when he came back he invented the story to account for it.”

“But he had told this man about seeing the ora three years earlier.”

“Well, they’re a very patient people. Perhaps he waited three years after he found the treasure before he dug it up.”

“I should say they’re patient!” cried Frances. “Perolli, if you don’t tell them we are simply dying of hunger, I will! It’s almost two o’clock in the morning. Do they think we are made of—cast iron? I want something to eat, and I want to go to sleep. Do they intend to talk until morning?”

“It is the custom, when strangers come, to talk to them,” said Perolli, severely. “Their only way of hearing news, and their only entertainment, is talking to guests. If you want to be rude about eating and sleeping, go ahead; I won’t.”

“Oh, all right,” Frances relented, sadly. “Perolli, do you believe in ora?”

“Well—do you believe in heaven and hell, and God and the devil? There are lots of things in the world that you don’t see or touch. I don’t know——” He said, briskly, “Of course I don’t believe in ora!” He wavered again. “But when you know so many people who have seen them and talked with them—I mean, who think they have——Everyone used to believe such things, long ago, and perhaps, here in these mountains, where the people have changed so little through all the centuries, there may still be things—spirits, phantoms, whatever you like to call them. Understand, I don’t believe it. But there may be something in that myth that’s part of every religion, that there was a time when there were other beings on earth besides men. And if there were once, why then, if we could still see them, they must still be——But of course it must be all imagination.”

“And there was that sound we heard. I never heard anything like it before. Perolli, you said it was an ora.”

He looked badgered. “I meant, whatever it was, it is what these people call an ora.”

“Do the ora ever come into this village?” I demanded at large.

“We hear them in the village at night,” said the coffee maker, quite casually, as he measured a spoonful of brown powder into the tiny pot. “No, we never see them. They call to us, and when we answer they talk, but we cannot understand their language. Always when we speak to them they answer in their own tongue.”

“But, Cheremi, you heard them talking about your cousin’s death,” I said.

“We hear them talking together sometimes, yes,” said the coffee maker. “If you go through the Wood of the Ora at twilight you will often hear them talking in some language you will understand—in Persian or Arabic or Greek or Albanian. Then if you listen perhaps you will hear them speak of you or of some one you know. But if you speak to them, they will be silent, and then they will go on talking together in their own language, which no man understands. It is no doubt the old language of the trees.”

“But you cut the trees,” said Alex.

“Yes,” I cried, struck by it. “You cut all the branches off the trees. Doesn’t it cripple or hurt the ora?”

“The ora is a spirit,” said the man of Ipek. “You cannot hurt a pure spirit that has no body. Ora are spirits of the forests, but they are not part of the trees. I understand it, but I do not say it very well. Even if you cut down a tree you do not kill the ora. An ora does not live, an ora simply is.”

We were interrupted by Cheremi, who approached, knelt mysteriously by Perolli’s side, and whispered. Perolli turned to us. “Our dinner is delayed,” he said, “because they can find nothing to give to Rexh. They have only pork in the house, and they have sent through all the village and cannot find any eggs or goat’s meat. A boy has gone now, over the mountains to the next village, to get something they can offer a Mohammedan. You see, their flocks were destroyed when the Serbs retreated through here, and if they kill one of the two sheep for us, it means losing the lambs next year.”

“But, Miss Hardy, I can eat corn bread. That is all I need,” said Rexh, earnestly.

“We can’t tell them that now. We should have thought of it sooner,” said Perolli. “We must wait at least until the boy comes back.”

“Oh, my sainted grandmother!” cried poor Frances. “Aren’t we going to have any dinner at all till breakfast time?”

“Is it because we are guests that our hosts are taking all this trouble to give Rexh the food a Mohammedan can eat?” I asked. “They’re Roman Catholics, aren’t they? Shouldn’t we have brought a Mohammedan into their house?”

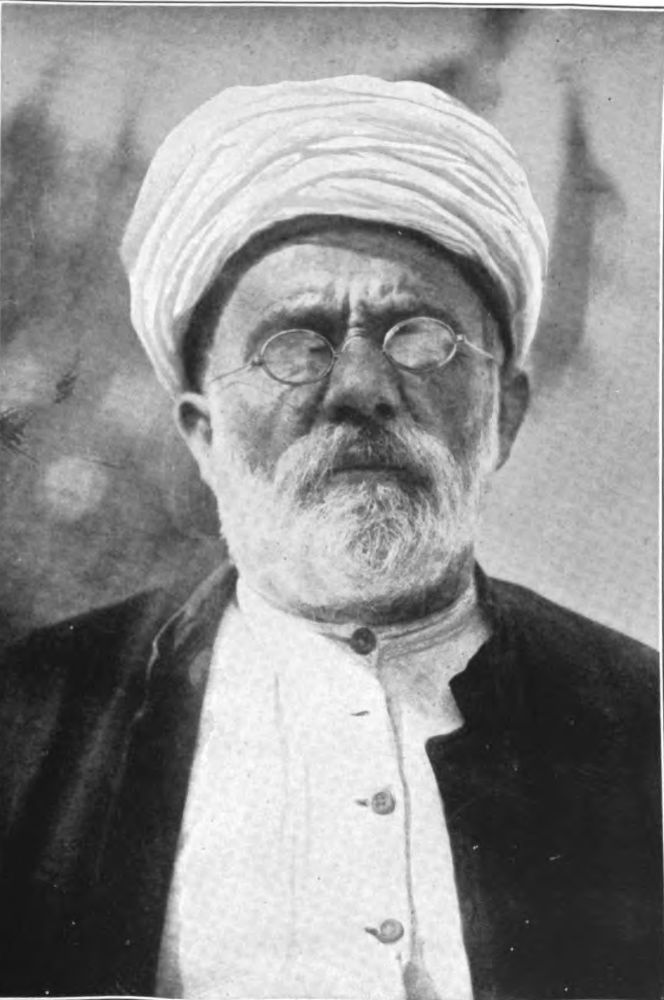

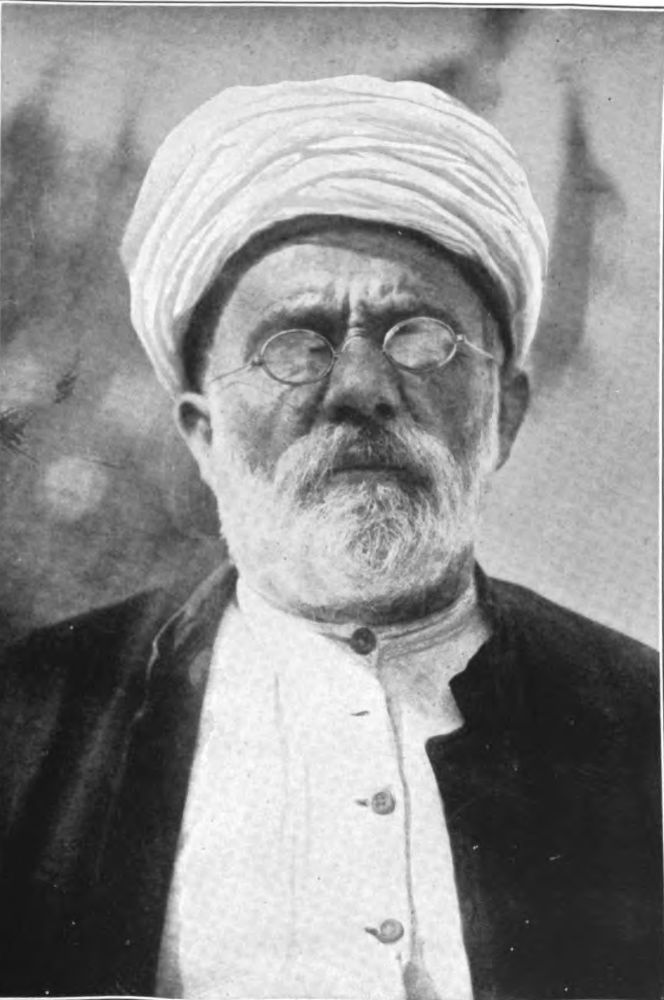

AN ALBANIAN HODJI OF THE MATI

“Oh, that makes no difference,” said Perolli. “One religion or another—all religions are the same in the sight of God. Mohammedan or Catholic, we are all human, we all respect one another. No, our hosts don’t mind the trouble; they’re only sorry that they have nothing but pork in the house.”

“What would happen, Rexh, if you ate pork without knowing it?” said I.

“Nothing, Mrs. Lane. Nothing would happen even if I ate it, knowing I was doing it. But for me it is wrong to eat pork, so I would never do that. For these others,” he explained, carefully, looking very serious and very twelve-year-old, “it is not wrong to eat pork. It is not the pork itself that matters, Mrs. Lane. It is doing what is wrong that matters. See”—he sat up, making his points gravely with straight forefinger—“some things are wrong for the Catholics to do; they are right for me. I can have nine wives, but the Catholics can have only one. They can eat pork, but that is wrong for me. There are many things like that. Each must do what he thinks is right. It does not matter what it is. Men think differently. But God knows whether they do what seems right to them. And in the end we all go to the same heaven, if we have been good.”

“Goodness, Rexh!” I murmured, feebly. I ask you, is that the talk you would expect between Mohammedan and Catholic in the Near East? What about massacres, and holy wars, and all that?

“What about them?” said Perolli, when I asked him. “They may be in Asia Minor—though, myself, I think religion hasn’t much to do with the fighting between Christian and Turk. But we don’t have them in Albania. We are all Albanians, first. And second, the Virgin Mary is the mother of all good people, Mohammedan or Catholic. Why should we fight each other?”

And he told of Italy’s attempt to block Albania’s entry into the League of Nations by asserting that the people were Mohammedan, and of the Albanian Mohammedans’ quiet retort in sending to Geneva a delegation led by an archbishop followed by I forget how many bishops. Then he told about the people in Kossova, who are both Catholic and Mohammedan, going to the mosque by day and attending mass by night; that is because they were conquered by the Turks, who told them they must become followers of Mohammed. “Very well,” they said, since it made little difference to them. But then the priests told them that they must not forsake the Church. “Very well,” they said again. And they are called in Albania a word which means, “half-and-half.”

“All that is not important,” said Perolli, his attention wandering, for the group around the fire began to talk Albanian politics. Behind his casually cheerful brown eyes I saw many things stirring, and I lay back, staring up at the smoke beneath the roof and wondering what was in all the hidden minds around me. Did our hosts suspect that Perolli was part of the new, distrusted Tirana government? Why, really, was he in these mountains? Was it truly only a vacation, and was he taking his life in his hands and wandering along the edge of the Serbian armies’ lines merely for pleasure? What were the real thoughts of these barbaric-looking men, these men with shaved heads and scalp locks hidden beneath their turbans, as question and answer and argument went back and forth across the fire?

They were talking in perhaps six languages; not everyone there understood all those tongues, and subtle conversations beneath conversations were going on; this man dropping into Italian for a phrase, that one into a dialect of Samarkand or northern India. And there was one man who persistently talked Serbian to Perolli—that language, at least, I could recognize, and I could see him growing restive under it, trying to take the talk into Albanian instead.

The children who were still awake sat soberly listening, not speaking, but gathering it all into their minds, turning their eyes from speaker to speaker as the languages changed, puzzled a little, trying to understand. And I realized how Albanian children get their education.

“We’d be saying: ‘Run away and play, dear. This isn’t for children,’” I commented.

“We wouldn’t,” said Frances. “They’d have been in bed six hours ago. How on earth do they live to grow up?”

“Heaven knows. But aren’t they strong and beautiful when they do!”

“It’s all right,” said Perolli, aside. “They’re talking about the French—whether France will become enough afraid of Jugo-Slavia to side with Italy down here. They aren’t for or against the Tirana government; they don’t exactly understand it, but they’re waiting to find out. They don’t know who I am. Don’t be worried.”

And at last dinner appeared. It was exactly half past two in the morning.

Most of the children—they had had no supper at all, so far as we could determine—were going to sleep, collapsing in soft little heaps where they sat beside the fire. Various women of the household lifted them tenderly, carried them to the farther corner of the house, near the goats, and laid them in a row on the floor. There, covered head and foot with heavy, tucked-in blankets, they continued to sleep.

Meantime the table was brought for us. It was a large round piece of wood, raised on little legs perhaps five inches from the floor. We sat about it, comfortably cross-legged on our blankets, and before each of us was laid a large chunk of corn bread broken from the flat loaf. In the center of the table was set a wooden bowl filled with pieces of pork.

“Don’t!” said Perolli, quickly, restraining our famished gestures. “In Albania it is not good manners to be eager to eat.” So we sat wretched for some moments, savoring the delicious odor of food that we must not touch, and politely making conversation with our hosts, who still sprawled in graceful attitudes about the fire. Then, with slow and indifferent movements, we fished out bits of the meat with our fingers, and ate.

It was delicious, the lean meat, stripped of every scrap of fat and broiled on sticks over a wood fire. We ate eagerly, biting first the meat, then a morsel of corn bread, coarse, made without leavening, but sweet and nutty. The smallest crumb of it must not be scattered on table or floor; when one fell, Perolli instructed us to pick it up and kiss it. We should also have made the sign of the cross, for bread is sacred in these mountains. Since we were not Catholics, that omission might be overlooked. But we must pick up the crumb and kiss it; to have ignored it would have been scandal.

“In Albania,” said Perolli, “it is etiquette to leave a great deal of the food.” And while we were still starving, after fourteen hours of hunger, he ordered the dish away.

After that, another wooden bowl filled with cubes of the fat pork, fried crisp. Rexh, sitting a little apart, soberly ate his piece of corn bread, for not even in the next village had the messenger been able to find eggs or goat’s meat.

When this second course was removed, fresh water was again brought to wash our hands, while the table was removed to a little distance. Then I saw why it was courteous to leave food, for all the villagers who had come in to see us gathered around this second table. And when they had finished and all had washed their hands—it was now past three in the morning—the table was again moved, and the family ate, men and women together, chatting and daintily dipping into the common dish.

“Do you think, Perolli,” said Frances, “that we could go to bed now?” And she looked enviously at Alex, who sat stony eyed, upright, and fast asleep.

“Oh, surely!” said Perolli. “They’ll understand that you’re tired.” And he explained this to our hosts, who nodded, smiling. So Cheremi and Rexh spread our blankets more smoothly on the floor, and we lay down in a row, our heads on our saddlebags, and pulled another blanket over us.

For a time the others sat by the fire and talked; one roasted coffee over the coals in a long-handled pan, and then ground it in a cylinder of brass. The warm brown smell of it and the sound of grinding kept coming through my daze of fatigue. Then one by one they lay down, covering their heads with blankets; the fire died to a fading glow of coals; there was no sound except the incessant tinkling of the goats’ bells and the crunching and tearing of the dried oak branches which they munched.

“My first night in a native Albanian house,” I thought, and the next instant, it seemed to me, I started awake. The room was full of movement and talk. It was still dark, but in the farther corner a gray, slanting block of light came through the open door; smoke curled and twisted in it. The fire was blazing; near it a man knelt, making coffee. All around him men stood, twisting tighter their long colored sashes; the rifles on their backs stood upward at every angle. Then I saw the goats and sheep going one by one through the block of gray light; a boy followed them, rifle on back and staff in hand, and I realized that it was morning.

I looked at my wrist watch, whose radium dial shone in the darkness. Half past five. The man who was making coffee smiled at me. “Long may you live!” said he, warmly, offering me the tiny cup with one hand, the other on his heart. As in a nightmare I struggled to reach it, and made my stiff lips say, “And to you long life!”

Perolli sat up quickly, wide awake as an aroused animal. “Good morning!” said he, happily. “Time to get up!”

Rain was still sluicing down from a gray sky; every rock in the interminable ranges of mountain peaks seemed to be the source of a foaming stream. Frances, Alex, and I, with our toilet cases in our hands, made our way along the side of a cliff to a waterfall, knelt on the dripping rocks beside it, and washed and brushed our teeth. The woman who accompanied us watched us with interest, and exclaimed, while we showed her the tooth-paste tubes, the tooth brushes in their cases, the cakes of soap, the jars of cold cream, the strange machine-made Turkish toweling, and the white combs. Even to ourselves they seemed exotic luxuries. How many curious things we have invented for the care of our bodies, since the days when we lived as the mountain Albanians still live.

“And at that,” I said, enviously, “I wish I had her complexion!” The woman stood by the waterfall, as graceful as a cat, strong limbed, clear eyed, fine skinned, and her bare feet in the cold water were joys to the eye, slim, beautifully formed, arched, with almond nails and a rose-marble color. True, her face and hands were grimy with wood smoke, and ours, when we looked at one another, set us off into exhausting laughter.

“My house is clean,” said the woman as she watched us scrubbing and scrubbing again. “There are no lice in it.”

“Now I wonder where she got that idea?” said Alex. “I thought they thought lice were healthy.”

Frances asked questions in Albanian. Yes, this house had kept for a time a refugee child on his way from the American house in Scutari to the lands of his tribe, and he had insisted on washing his bed and his clothes; he had hated lice with an astonishing hatred; he said they were small devils who would grow to be large devils, and the woman did not think this was true, but she had washed all the beds, also all the house, and now it was like an American house and had no lice.

“But that isn’t what she meant. She meant that she doesn’t see why we are washing,” said Alex, lifting her dripping face above a pool and rubbing it with one hand. It isn’t easy to wash in a waterfall, with no place to lay the soap.

“We do this every morning,” Frances explained in Albanian. “It is American custom.” The woman looked as though she thought it rather foolish, still, if it were the custom——

“Also,” said Frances, “every morning we wash the children and the babies, all over, from head to foot.”

“Yes?” said the woman, indifferently. “Here babies stay in their cradles. Children go into the water when they are old enough to swim. Then only in the summer, when it is not cold.”

Frances gave it up. We came back from the waterfall, on a path that was like a terrace of heaven overlooking all the world of mountains and valleys and swirling clouds. We were already wet to the skin with rain, but that did not matter, for we had before us the day’s walking in it, and our indifference to wet clothes and feet was already quite Albanian. And the morning, and the mountain air, and the water-gushing range after range of mountains, seemed to us glorious. We thought that it would be fun to herd goats among these peaks and to live forever in a stone house with a fire on the floor and a pan of corn bread baking in the coals. No dusting, for there was no furniture; no making of beds, for there were no beds; no curtains to keep fresh, for there were no windows; no trouble with clothes, for centuries saw no change in fashions; no work except hand weaving and embroidery and the washing of linen in a brook. No haste, no worry, no struggle to invent new needs that one must struggle to satisfy. All that simplicity and leisure our ancestors traded for a rug on the floor, a trinket-covered dressing table, for knives and forks and kitchen ranges, fountain pens and high white collars and fashion books. It seemed to us, on that morning, a trade in which we had been cheated.

And even now I wonder, sometimes, about the value of the centuries that have given us civilization.

We had no doubt at all about their worthlessness that morning, when we set out again—after a cup of Turkish coffee, each—to walk another twenty miles over the Albanian mountains, through the Wood of the Ora and the tribal lands of Plani and over the Chafa Bosheit to the next village.