CHAPTER XII

THE SONG OF THE LAST GREAT WAR WITH THE DRAGON—AN UNEXPECTED BANDIT—HOW AHMET, CHIEF OF THE MATI, WENT BY NIGHT TO VALONA—THE RAISING OF SCANDERBEG’s FLAG—AN ALBANIAN LOVE SONG.

They made places for us, laid another handful of dry twigs on the fire, and rolled fresh cigarettes. The Lumi Shala was rising higher than they had ever known it to do, they said, and the Drin was overflowing in the Merdite country. And learning that we were from Scutari, they asked us what we knew of the Tirana government, of which they had heard. Was it true that the Land of the Eagle was free?

Leaving discussion of politics to Perolli, we sat cross-legged, looking into the straight lines of rain that covered the mouth of the cave like a curtain. Faintly through them we could see a blueness of mountains and a greenness of fields beyond the narrow rust-red ledge of the trail. Time passed, with a murmur of talk and a crunching of leaves, until Rexh touched my elbow.

“Here is a man, Mrs. Lane, who knows the end of one of those songs. He does not know it all, but he can sing about the eating, after the war was ended. He will sing it for you, if you want him to.”

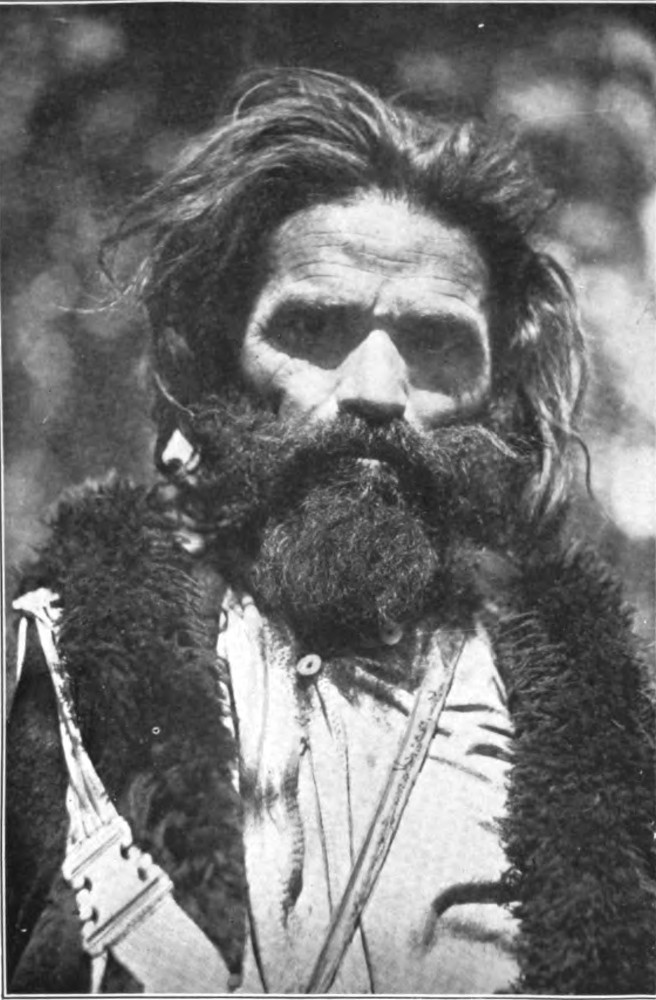

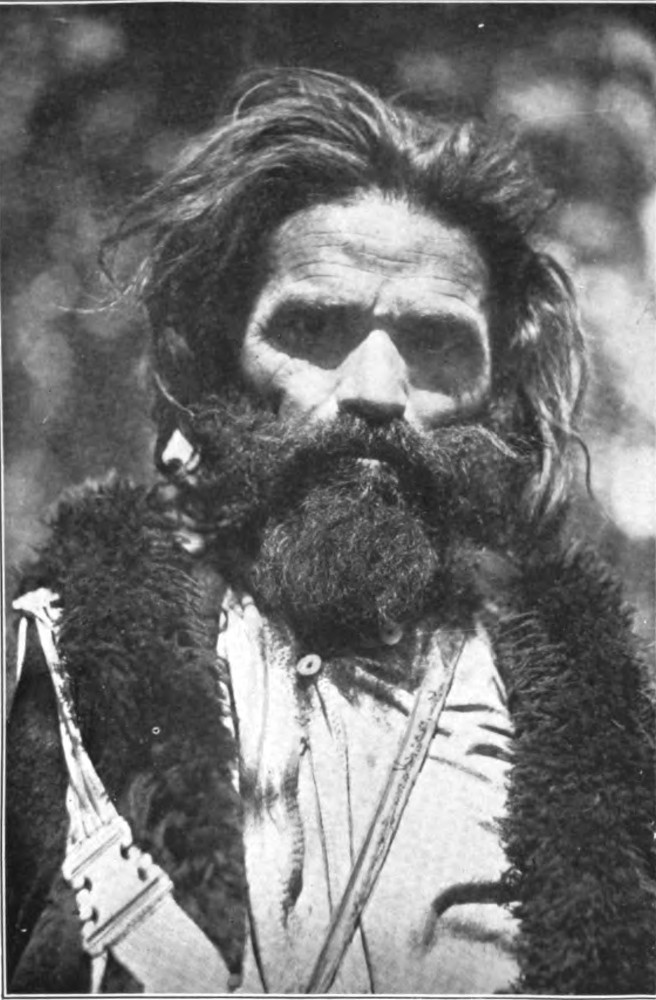

He was a grimy man, barefooted, ragged, and incredibly whiskered. But he carried besides his rifle on his back an old beautifully made musical instrument somewhat resembling a mandolin, with a long neck ending in a carved ram’s head. It was strung with fine wire, and he handled it proudly; the wire, he said, had come from Scutari. In his father’s day it had been strung with horsehair and played with a bow, but at the time of his own marriage he had sent to Scutari for the wire, and he now played it with a finger nail. Fresh cigarettes were rolled and adjusted in holders, knees were crossed comfortably, and the song began.

It was only a fragment—the last song of all the songs about that great war of the dragon and the drangojt above the Dukaghini mountains. The strangely pitched twang of the wire accompanied the words, chanted in a wild rhythm to the rain-filled valley of the Lumi Shala:

“The ora of Shala came from the deathless forest,

From the wood that is always green beyond the Mali Nicaj.

The ora of Shala saw the war in the air above the forest,

She saw the war in the air above the crashing peaks,

She saw the blood of the dragon spilled on the rocks.

Ho lo! Ho la! The head of the dragon falls!

Ho lo! Ho la! Two heads of the dragon are dead!

Ho lo! Ho la! Three heads of the dragon fall on the rocks!

The men of the earth are saved!

The ora of Shala screamed the word that the earth was saved.

Three times the ora of Shala screamed,

And her scream was heard on the Mali Nicaj,

Her voice was heard on the Chafa Morines,

And the Lumi Shala ran through the valley of Shala.

Three times the ora of Shala called,

And the ora of all the mountains came to her call,

They came like sparks from a fire to the ora of Shala.

‘Oh, my sisters, this is the word from the battle.

The dragon is dead and the world is saved!

The brave drangojt have saved the world.

The mountains stand without moving forevermore,

And the waters go back to their places,

For the brave drangojt have saved the world.

We will make a feasting for the saviors of the world.

My sister, go to the field for grain,

Cut it and thresh it and grind it,

Make bread and bake it well.

My sister, go to the mountains among the flocks,

Find a sheep with a lamb beside her,

Ask the sheep to give you her milk,

For we make a feast for the brave drangojt.

My sister, go to the tree that is hollow,

To the tree where the honey is made,

And ask the bees for their yellow honey.

My sister, here is a knife that is sharp;

Strike true, strike deep, strike quickly,

And bake the meat in a heated pit.’

The first ora came with bread on her head,

The second ora came with a sack of milk,

A milk sack made from the skin of trees.

The third ora came with her hands full of honey.

The fourth ora came with two roasted animals,

Large roasted animals, hot and brown.

Now we can go to our brave drangojt.

The hair of the ora was unbound,

And their heads were crowned with flowers,

And the beauty of the world was their garment.

The ora of Shala came first to the Mali Riges,

The ora of Shala came to the camp of the drangojt.

‘I hope we find you well, heroes of the earth,

Long may you live, the courage of the world.’

Then rose and spoke Lleshi of Lleshi,

Chief of the tribe of the Merdite drangojt.

‘Welcome to you from wherever you come.

Where have you been hiding your beauty?’

‘I am the sister of the ora of the Merdite,

She who is guarding the Mali Mundelles.

I am the ora of Shala.

Long live the heroes who have killed the dragon,

Long live the warriors who have saved the world.’

Then on the grass they sat for the feasting.

All the ora turned back their sleeves,

Making ready to serve the heroes.

The first ora broke the round loaf of bread,

The second ora brought the hot roasted meat,

The third ora brought the bowl of yellow honey,

The fourth ora poured the milk from the sack.

All the ora brought good water from the spring,

And the drangojt drank from the cup of their hands.

When the feasting was ended they left that place,

They washed their hands in flowing water,

They lay by a fire on a carpet of leaves,

And they spoke of many things pleasant to hear.

They spoke till the star of the dawn came out

Above the peaks of the Mali Mundelles.

The star of the daylight came out,

For the power of the dragon was broken.

This was the feast of the Merdite drangojt

After the last great war with the dragon.”

The player ran his finger down the wire in a final weird whine, and the instrument lay silent on his knees. “That is all I know of that one,” he said. “But if the American zonyas would like to hear other songs, I can sing them, for I am a bandit.”

I cannot describe the shock we felt at those simple words. “Jam comitadj.” Yes, he had said them. Or had he?

“Comitadj?” said I, noticing a strange stiffness in my lower jaw. “Nuk comitadj?”

“Po,” said he, quite calmly. And the modesty which reveals too great pride touched his voice as he added, “I have been a bandit for many years.”

Automatically my eyes sought Frances’s. Hers were widely open, and expressed only a shock as great as mine. We both turned a fascinated gaze upon the bandit, who had laid aside his musical instrument and rested a fond hand on his rifle. “For many years,” he repeated.

“Do you like it?” said I, weakly. “Do you like—banditing?”

I had read of bandits in the Balkans, and I had heard of them, and I had even thought how self-possessed and cool I would be if I encountered one of them. “Certainly,” I would say, with dignity. “Take my money if you like; it is very little; you are welcome. But there will be no use whatever in your holding me for ransom, because——” I suppose everyone falls into these absurdities of imagined and impossible conversations. The lure of them is their offer of escape from reality. Certainly I had never believed that a real, living bandit would step out of that fantastic realm and be a solid figure in the daylight. I, I in a bandit’s cave! Such things didn’t happen; they were only in books. So I said, meekly, timidly, quite inadequately, “Do you like—banditing?”

THE BANDIT WHOM WE MET IN THE CAVE ABOVE THE LUMI SHALA AND WHO SANG US THE SONG OF DURGAT PASHA

A letter just received from Albania brings the news that he has cut his beard, hung his rifle on the wall (when disarming the mountaineers the Albanian government made an exception in his case), and is now running, with considerable success, a sawmill in the Mati.

Yes, he said, he liked it very much. He became even poetic about it. I admit I took no notes of what he said. But I recall Rexh’s voice repeating lyrical words about life on the mountains, camp fires and stars, freedom and fighting—the only life for a man, he declared. Once he had stopped being a bandit and gone back to the life of houses, but he was glad when the time came to be a bandit again.

I had not thought that being a bandit was a seasonal occupation, and I begged an explanation of these mysterious words. It developed that they referred to wars unknown and unrecorded save in the songs of the mountaineers, and we became so involved in references cryptic to me, but clear to the listening Albanians, that at last I was obliged to beg him to begin at the beginning and tell the straight story of his life. This he did, with the modest reluctance of a hero surrounded by admirers.

“I was not a rich man,” he began, “but as our saying is, ‘The smallest hair has its own shadow.’ There were sheep in my house, and it was a house of two rooms, and the fields repaid our labor. The tobacco box in my sash was never empty, and there was bread in the baking pan. There was a son in the cradle and another by the fire, and life was as smooth as the Lumi Shala in summer, until the coming of Durgat Pasha.

“After that came the treason of Essad Pasha, and, having then neither house, nor sheep, nor sons, nor tobacco, but only my rifle——”

We must interrupt, to bring him back to Durgat Pasha, and he was astonished that more than that name was needed to make us understand. Had we never heard the songs of Durgat Pasha? Durgat Pasha, who in 1912 came from the Sultan of Turkey to subdue the Sons of the Eagle? Durgat Pasha, who burned and killed, from the Mali Malines to the Malit Shkodra? He bent over the instrument on his knees, twanged three wild notes from it, and sang:

“Seven Powers had called a council,

Seven Powers met and said,

‘Shqiperia is no more in our hands,

All Shqiperia is not in our hands.’

Then rose Durgat Pasha and took his gun.

‘Leave this to me for three years.

O Sultan, I go for three years.

When I return the Shqiptars are yours.’

Durgat Pasha came past the white lake,

Durgat Pasha to the Mali Malines,

Durgat Pasha to the Mali Shoshit,

Durgat Pasha and five thousand soldiers.

He sends word to Hasjakupit,

‘You shall send your rifle to me.

Thirty Turkish pounds have I paid for my rifle,

Thirty pounds for my own rifle,

But I leave houses and lands and go with my rifle.

Thirty houses I leave behind me.’

These were the words of Hasjakupit.

‘Thirty houses I leave behind me,

And into Montenegro I go.

I go to King Nichola of Montenegro;

He will give me meat and bread.’

Durgat Pasha on the top of the mountain,

Durgat Pasha with Shala around him,

Durgat Pasha had no bread or water,

Durgat Pasha’s rifles had nothing to eat.

And the fighting men of Shala were all around him,

The fighting of Shala was terrible.

Durgat Pasha went out of his way to Puka.

Puka and Iballa greeted him.

When he came to Bashchellek

All of Scutari came to greet him.

The people of Scutari were frightened.

Durgat Pasha was going to die,

And Scutari rubbed his face with a sack,

Scutari gave him food and drink.

Then rose Salo Kali of Scutari.

‘My rifles I cannot give,

I have made besa with one hundred men;

Our rifles are not for Durgat Pasha.’

‘Leave the besa, Salo Kali,

Take your hammer and shoe the horses.

That is your business, Salo Kali.

What have you to do with rifles?’

‘I have made besa with one hundred men;

Our rifles are not for Durgat Pasha.’

Durgat Pasha rubbed his forehead.

‘I have never seen this kind of people,

I never saw a nation like Shala or Shoshi.

What can be done with the Shqiptars?’

These were the words of Durgat Pasha.

“That is the song of Durgat Pasha,” said the bandit. “When I came home from the fighting, the men of Durgat Pasha had burned my house, and my wife and my sons were dead. It was then I gave besa to myself never to hang my rifle on the wall and never to cut my beard until all Albania was free. And I went to fight the Serbs at Chafa Bullit. That was good fighting. All day we fought, and at night we lay by the camp fires and the women gave us bread and meat. All day long, while we were fighting, the women were on the trails bringing us bread and meat. Then we were tired and slept, and the air was good, not like the air in houses. And in the morning, when the stars were pale, we raised the war cry and killed more Serbs. It was a good life.

“It was at this time that the chiefs of Kossova came secretly by night through the Serbian lines to the house of Ahmet Bey Mati, and I was called by Ahmet to take them to Valona. He said that a word would be spoken in Valona to make Albania free. I said to Ahmet: ‘The Montenegrins hold Scutari and the seacoast even to San Giovanni, the European Powers are in Durazzo, the Serbs have Kossova and the Dibra, the Greeks are in the south. What is talk of freedom? This is not a time to talk; it is a time to fight.’ Ahmet said, ‘Before the war cry, the council of chiefs.’ Ahmet is chief of the Mati, head of the family that has ruled the Mati since the days of Scanderbeg. He was a boy of sixteen, newly come from the court of Sultan Abdul Hamid; he did not wear the clothes of the Malisori, and the chiefs of the Mati laced his opangi before every battle, because he did not know how to lace opangi. Yet it must be said that it was his coming that saved the Mati from the Serbs. He came quickly, killing seven horses between Monastir and Borelli, and he told the chiefs what to do, and they saved the Mati. It was hot fighting. For five months he had been fighting and sleeping on the rocks. His chiefs loved him.

“I said, ‘I am killing Serbs, and have no wish to go to Valona.’ Ahmet said: ‘When my father died, my older brother sent me from my country to the Turks. I do not know the trails. The chiefs of Kossova are my guests, and they do not know the trails. We must go to Valona through Elbassan, where the Serbs are. There is a meeting of all the chiefs of Albania in Valona. If we are killed by the Serbs, there will be no chiefs of the Malisori at that meeting. There will be only Toshks—men of the plains.’ I said: ‘To-night the moon will be dark. We must start as soon as we can see the small stars.’

“In three nights we were at the house of Asif Pasha in Elbassan. No, nothing disturbed us on the way, except that we were obliged to kill with our hands the dogs that sometimes came upon us from the villages. The Serbs were everywhere, and we could not use our guns. When we came to the house of Asif Pasha, the chiefs of Kossova with Ahmet slept in one room, and I sat with Asif Pasha by the fire in another room. Elbassan was held by many hundred Serbian soldiers. At midnight five officers with thirty soldiers came to the door. They came in, and would not take coffee. They stood, and said: ‘Who are the twelve men who sleep to-night in this house? Do not lie, for we know that they are here.’

“Asif Pasha said, ‘This is one of them.’ I said, ‘I will tell you who they are, but I beg you not to let them know that I have told. I am only a servant, and they are great chiefs. They are byraktors of five villages of the Mati, three villages of the Merdite, and three villages of Shala and Shoshi. They have come to Elbassan to talk with the Serbs. They have come secretly, hiding from the other chiefs. I do not know why. I beg you not to tell them that I have told, for they are tired and dirty, and they are sleeping while the women clean their clothes so that they will be clean to-morrow when they go to speak to your chiefs.’

“The officers sat down then, and one of them wrote. He wrote the names of the chiefs as I gave them to him, and he wrote what I said, that the Malisori were tired of fighting, and had little ammunition, and did not like their chiefs that made them fight. While he wrote, Asif Pasha gave them rakejia, and more and more rakejia, but no coffee. When the Serbs had become foolish I went to the other room where the chiefs were listening with their rifles in their hands, and I took them all by a way I knew, out of Elbassan.

“So we came to Valona, to the house of Ismail Kemal Bey Vlora, the same who had been Grand Vizier of Abdul Hamid. He had come on an Austrian warship to Durazzo, and there they had tried to kill him, and he had come secretly, as we had come, to Valona. Valona was the only free village in Albania then, except our mountain villages. There was a council in his house. Chiefs of all the tribes from Kossova to Janina were there, and when the council was ended Ismail Kemal Bey brought the flag of Scanderbeg, which had always been hidden in his house, and with a rope he made it run to the top of a pole on his house. It was the red flag with the two-headed black eagle on it. I stood in the street and saw it go to the top of the pole. The chiefs were on the balcony, and Ismail Kemal Bey wept. Many men had tears on their cheeks. In the streets they cried, ‘Rroft Shqiperia!’ and embraced one another. They said that the spirit of Scanderbeg lived, and that Albania was free. But I said, ‘The time has not come when I can hang my gun on the wall or cut my beard.’

“The next night I started secretly back through the Serbian lines with Ahmet and the chiefs of Kossova, to come to our own mountains and kill the Serbs. We had been twenty-two days in Valona, and for those twenty-two days I had not been a comitadj. I was glad to be one again.”

For the moment the fortunes of war were with the drangojt; the heavier clouds had been driven away, and a pale sunshine fell on Shoshi, which looked like a water-color picture in a gray frame. Our side of the valley was in shadow, but the rain had ceased and we should have been going on. I was held by a still unsatisfied curiosity about that bandit.

“I thought bandits were highwaymen,” I murmured, and, unwilling to ask interpreters to put the question that was in my mind, I laid the burden on my own lame knowledge of their language. “You kill Serbs?” I asked. “How do you get money?”

The whiskered face seemed to smile broadly at this boldness. “I get it on the trails,” he said.

“From Albanians?”

“I get it where I can,” he answered, indifferently. “The Austrians had money, and there were many Austrians in Albania. This rifle came into the mountains on an Austrian officer. I gave his clothes to a naked man of Dibra who was fighting the Serbs there. I got four Italian capes and trousers in one day, on the road north of Scutari, and there was money on their bodies, too. As to Albanians—there was a rich Albanian once, whom I met riding out from Ipek. Why should a man of Albanian blood ride in the eyes of the Serbs with gold in his pocket, while true Albanians are dying of cold and hunger? I took from him everything he had, and left him on the trail as naked as he came to the cradle. I said to him, ‘You are the Sultan, and I am the Grand Vizier. In your name I will give these things to your people, and they will be grateful.’”

We laughed hastily.

“But it is time to cut your beard and hang your rifle on the wall,” Perolli suggested. “There is a free Albanian government now.”

“But not a free Albania,” said the bandit. “The government forgets that, and sits in council with the Powers that sold us to Italy and gave us to Serbia. Have you forgotten Kossova and a million of your brothers who are slaves to the Serbs?”

“I am of Ipek,” Perolli answered him. “Nevertheless, I am first a Shqiptar and second a man of Kossova. And I remember our proverb that says, ‘Better an egg to-day than a chicken next year.’”

“We have also a saying, ‘Better the nightingale once than the blackbird every day,’” replied the bandit.

“Let it be. ‘Every sheep hangs by her own leg,’” Perolli retorted, rising.

The honors were with him. For the moment, the bandit could think of no proverb which would be a weapon, and could only reply to our courteous farewells by wishing us smooth trails.

“The good man of yesterday becomes a burden to-day and a danger to-morrow,” said Perolli, as we went slowly along the ledge of trail. “Why is it that our minds do not change as rapidly as the world changes around us? These mountain men will cling to their rifles, though the time is past when killing will solve our problems. Stupidity! But sometimes I think the whole world is stupid.”

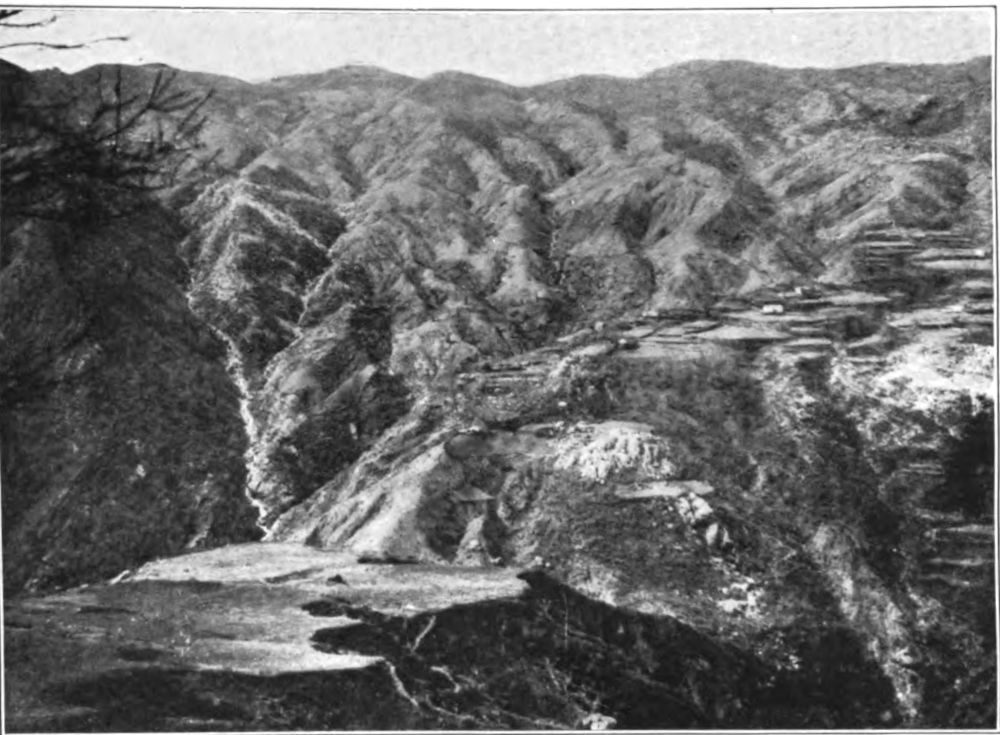

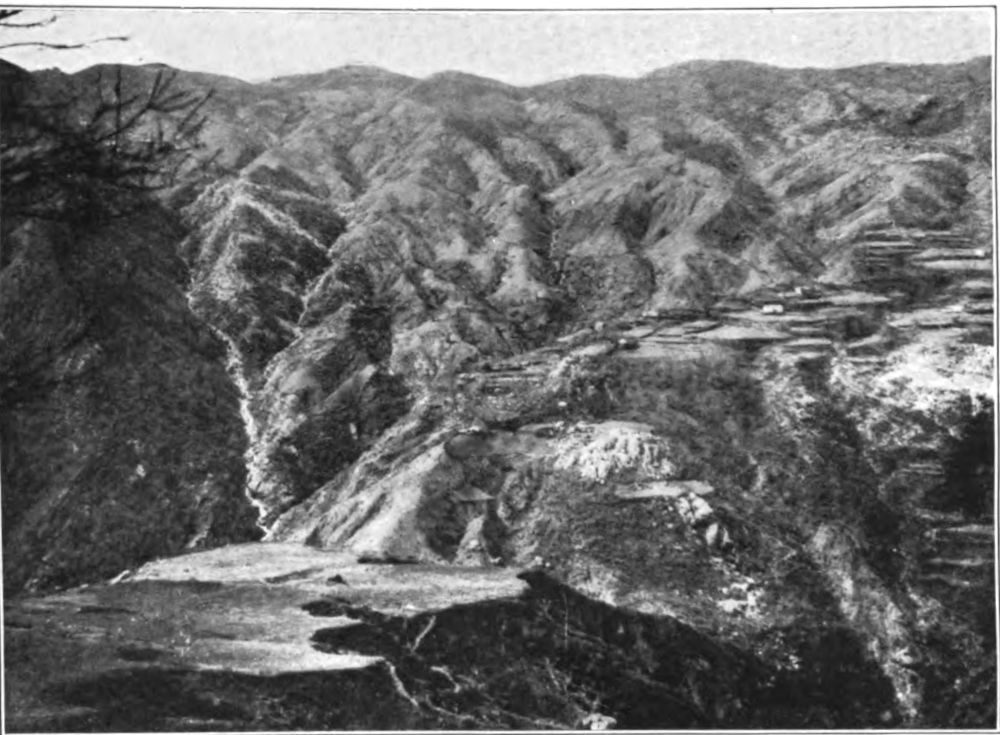

We agreed with little assenting sounds, our minds too much occupied with the difficulty of the way to spend energy on words. We were absorbed in the narrow, slippery trail running rust red along a cliff that wept iron. Only when we paused for breath did we see the beautiful valley of the Lumi Shala beneath us. The rain was falling gently now, a wavering veil of gray chiffon over the mountains that ran a scale of paling blues to the white peaks in the west. Below them little fields were green, burgeoning woods were faintly rainbow misted with colors of new leaves, and there was a foam of plum blossom and a sudden rosy note from a solitary peach tree.

We looked in silence. And when we resumed our toiling way, Perolli began to sing. It was a song with springtime in it, a song like the valley of the Lumi Shala, an Albanian song of strangely pitched half notes and indescribable transitions, breaking at intervals into the burbling melody of a bird’s throat. We listened entranced; we begged him to sing it again.

THE SHALA VALLEYS

“It is called ‘The Mountain Song,’” he said. “But it isn’t one of the songs of the trails; it is a song of the large villages of Kossova. I think it isn’t more than fifty or sixty years old, because it is a love song. Love songs are new in Albania, and you find them only in the villages.” And he sang:

“How beautiful is the month of May

When we go with the flocks to the mountains!

On the mountains we heard the voice of the wind.

Do you remember how happy we were?

“In the month of May, through the blossoming trees,

The sound of song is abroad on the mountains.

The song of the nightingale, ge re ge re ge re.

Do you remember how happy we were?

“I would I had died in that month of May

When you leaned on my breast and kissed me, saying,

‘I do not wish to live without you.’

Do you remember how happy we were?

“I wish again for the month of May

That again we might be on the mountains,

That again we might hear the mountain voices.

Have you forgotten those days of beauty?”

Again and again he sang it, while we tried to follow with our voices those unwritten notes that express so much more clearly than any words the beauty and fleetingness of spring. And when, unexpectedly, we came upon five young men drawn up in a line to greet us, we could not believe that the way had been so short and that we had come to the village of Shala.

It was indeed Shala, and in a moment we were being welcomed by the padre and escorted up a stone stairway into his rooms above the church.

These were better rooms than Padre Marjan’s; the windows were not broken and the walls were solid. But they were bitterly cold, and this priest was not our Father Marjan. He was older, squarer, more sturdy, his hair was iron gray, and his presence was commanding—so commanding that it was a bit chilly. He led us formally into a large, bare room, where there were a long table and four hand-made chairs; he gave us each a chair and himself remained standing, talking with grave formality, in Albanian, to Perolli. Little pools of water spread around our feet, as though we were umbrellas.

We sat there half an hour, an hour, an hour and a half. There was no fire; the room had the feeling of a room that has never had a fire in it. We suggested to Perolli that he take us into the kitchen to get warm, but he silenced us with a glance; indeed, it was obvious that we were in the hospitable hands of the priest and that it would be an unforgivable affront to make such a suggestion to him.

We were so cold from the first, holding ourselves so tight to prevent our shivering from becoming uncontrollable, that I do not know when the real chills began. It was Alex’s gray-blue lips and cheeks that first alarmed me. I said to Perolli that he must get us warmed. He said that before long we would have something to eat, and that would warm us.

Then I saw Alex’s cheeks turn to a hot, burning red, and I said: “Perolli! You’ve got to get Alex a chance to get into dry clothes. Can’t you see she’s ill?”

“Are you ill?” said Perolli, and, “Oh no, no, not at all!” said Alex, her teeth chattering together. “I would like to lie down, if I could, but it’s all right.”

Another half hour went by, lengthening into an hour. Alex seemed still more ill to me, though I could not see her very well; she grew very, very large before my eyes and then very small and far away. My head ached, and just as I thought I was warm at last, I would be disappointed again by a chill that made me clench my teeth and grip my chair. But when I saw Alex’s head fall forward as though she were faint, I could stand it no longer. I got up.

“Perolli,” I said, “tell our host we’ve got to get Alex dry and warm. If you don’t I’ll undress her and rub her right here!”

I would have said more, but I couldn’t. A pain like a knife stabbed through my lungs, and before I could catch my breath stabbed neatly again. It’s the kind of pain you can’t describe; if you’ve felt it you know it, and if you haven’t, you can’t. I recognized it; it had struck me years before and laid me in a hospital for six weeks. Pneumonia!

There’s a kind of clan morality that controls us. It has nothing to do with the moralities of religions or races or states; it is a group affair, and the groups seem roughly to be made by common occupations. Soldiers must conceal, and deny, their natural fear of death. Labor-union men must let their children starve before they “scab.” Farmers must not let their stock break through fences, or let a bit of unused land become a nursery for weeds. Employers—and one sees this, now, everywhere in Europe—must not pay higher wages than other employers, however easy and more efficient it may be to do so. Women who are married, or expect to marry, must not let a man’s fancy wander from the woman who claims him. Doctors must let a patient die rather than take the case from another doctor. And women like Alex and Frances and me—for whom there is no generic term, except the meaningless “modern women”—must never, so long as they can keep on their feet, admit that they are ill.

How Alex felt I don’t know; for myself, I was in a blue panic. I have never wanted anything so much as I wanted to collapse right there, in sheer terror. Pneumonia, in Shala, a hundred and fifty miles from a doctor, from medicines, from even a bed. Pneumonia, among the Albanians, whose only medical knowledge of it was that it came from drinking rain water!

Perolli had been surprised by my exclamation. “Why didn’t you say you were uncomfortable?” he said to Alex. “If I’d had any idea——”

“I’m all right,” said Alex, getting the words out quickly and shutting her teeth hard.

“Well, what are you fussing about, then?” said Perolli to me, anxiously. “I’d take you girls to a fire if I could, but, you see, they’re cooking in the kitchen, and naturally the padre doesn’t want to take his guests there. We’ve been here three hours now; dinner ought to be ready before long, and you’ll be all right as soon as you’ve had something to eat.”

That pain stabbed through my lungs again, taking all my breath and engaging all my self-control, and I wilted. I wasn’t the good sport Alex was.

“I know I’m abominably rude,” I said, “but I’m too tired. I want to lie down. Ask the padre if there isn’t somewhere we can lie down till dinner.”

It was too bad. Guests shouldn’t behave like that. There was another room, and it had a mattress on the floor, but there was no candle; a bit of blazing wood must be brought from the kitchen to light me into it; our bags must be fetched; the household was quite upset. I apologized and apologized, but at last I was able to tear off my sopping stockings, pull some of our blankets over me, and lie down in the darkness. I was falling into a kind of stupor. I could not get off my soaking garments, but it did not matter, fever kept me even too warm in them, and in a moment I—as the old-time novelists say—knew no more. During that moment I felt some one crawling on the mattress beside me, put out a hand, and touched Alex’s blazing cheek.

We were awakened and brought out to dinner. It did not seem real. I remember it like a delirium. There was hot soup, but each mouthful seemed a cannon ball to get through a closing throat, and there were corn bread and goat’s-milk cheese; the padre stood at the head of the table through the meal, holding the torch. He did not eat with us, Perolli said, because we were using all the dishes he had. It transpired, too, that there was but the one mattress in the house. The padre’s niece slept on it; he himself slept on the floor with a blanket. The niece was a sweet, round-cheeked little girl of about fourteen, quite the German Fräulein; she had been educated in Vienna and Munich, and seemed most desperately lonely in Shala, hungry for companionship and talk of the things she knew; but since the war and the wreck of central Europe she must stay in Shala. I saw a tragedy there. But I saw it very dimly through the mist of pain and fever.

Alex and I took the mattress, with the simple, direct selfishness of miserable animals; it was very narrow, but we lay head to foot on it and managed. Frances, Perolli, and Rexh slept in blankets beside us on the floor. All night long Alex moaned in her sleep, and I could not tell the difference between reality and delirium; only the knives in my lungs brought me out of the mists now and then to hear the ceaseless pouring sound of rain and feel the damp chill of the room.

In the gray morning Alex and I sat up and looked at each other.

“How do you feel?” said I.

“Fine,” said she. “Have you a fever?”

“Fever? Not a bit,” said I. “But I’ve been thinking. It’s the tenth, and I absolutely must be in Paris by the twentieth. It’s most important—a business matter. So I don’t think I’d better go on with you into the Merdite country. I think I’d better go back to Scutari and catch the boat from Durazzo next Tuesday.”

“But you can’t make it out of these mountains alone!” said she. “It’s a hundred and fifty miles and you don’t know the trails or the language.”

“Oh yes, I can!” I said. “Don’t talk nonsense, Alex dear.”

“Well, you know what it is. It is up to you,” said she. (How I love women for the way they love you and yet leave you free!) “Only, if you did have a fever, you realize it would be dangerous to try to make it, in this weather.”

“If I had a fever, it strikes me it would be equally dangerous to stay here,” I replied. “And I must be in Paris, on the job, by the twentieth.”

“Well, if it’s the job——” said she, and called Perolli.

Perolli was deep in politics, and paused only a moment to say that if he had any authority over me he would not listen for a moment to such a mad notion; but I told him he hadn’t and asked him to get me a guide. He said he did not know the men here, but would do his best, and by the time I was dressed he brought the guide, a slim, too-handsome youth who spoke Italian and swore to get me to Scutari in two days.

Frances said that if I would insist on going, I must take Rexh with me; and I said I would not dream of it, I would not think of letting that twelve-year-old give up the trip into the farther mountains. All along the way he had thought of little else, and half his sentences had begun, “When we get into the Merdite country——” We argued about it, Frances patient and I surprised to find how bad tempered I could be. The packs must be rearranged, and I kept putting my hand down on things that were not there; everything moved with incredible slowness, and eternities passed before I cut short the interminable formalities of farewell and plunged out into the cool, delightful rain.