CHAPTER XIII

THE BACKWARD TRAIL—THE MAN OF SHALA HAS A SENSE OF HUMOR—THE BYRAKTOR OF SHOSHI HEARS THAT THE EARTH IS ROUND.

We started down the bed of a waterfall, the guide and I; the bad going, the exhausting force of the current, my dizziness and breath-taking pains, made the first half mile a blur. When we came out on a cliff edge I sat down, and then for the first time I saw Rexh. He stood very gravely, watching me; the rain had melted the dye in his red fez and little streams of it ran down his round, serious face.

“It is much better for me to come with you, Mrs. Lane,” he said. “You do not know the language, and this Shala man he is a bad man.”

“But, Rexh, my dear!” I said. “No, no! You must go back to Miss Hardy and say that I say you cannot come.” He might never again have an opportunity to see that farther interior country; it was a trip to dream of for years and to remember always afterward. I had not asked him to give it up; I did not want him to. I was safe enough; all the tribal laws protected me; no one had any motive for injuring me, and the Shala man, however bad, knew that I had no money and that he would be well paid when he delivered me in Scutari.

“All that is true, Mrs. Lane. But I think it best for me to come with you,” said Rexh, inflexibly. And because I really had no strength for combating such determination, I got up and went on, the Shala man going before, with my pack protected by a poncho on his back, and Rexh following after.

We climbed up cliffs and lowered ourselves down them; we slipped and slid and jumped down more little waterfalls; we waded knee-deep streams and struggled over decomposed shale that clutched at our feet like sand; we came down a switchback trail to the banks of the Lumi Shala, and the Shala man carried me across it, on top of his pack. It was all like a nightmare, of which I remember clearly only my thirst. Though I was as wet as anything that lives in the sea, I could not get enough to drink, and every one of the millions of springs invited my drinking cup. Rexh, whose endless task was to fill it for me, protested. “In the rains, the water makes you sick,” he said. “It turns to knives inside you. You will be sick, Mrs. Lane.”

He was the funniest figure you can imagine, in a suit of striped American flannelette pajamas and the red fez that poured a dozen little wavering streams of dye over his forehead and down his cheeks.

If I were in France, I knew, the doctors would put me in a hot room with all the windows closed, and insist that I must not have much water. In America I would be given fresh air and water, and bathed to keep down the fever. Well, I was in Albania, and I reasoned that, if I was to have pneumonia, I might as well have it on the mountain trails as in a cold, wet house, and when I got to Scutari I could be as ill as I liked, with very little bother to anybody.

“If the water makes me sick, Rexh, and if I become gogoli, with a wild spirit of the mountains entered into me, you are not to mind,” I said. “You are to get me down to Scutari somehow; above all things, do not let me stay in a native house.”

“Yes, Mrs. Lane.” Then we began to climb up the next mountain, and, kneeling on a bowlder above me to help pull me up its side, Rexh said: “Your hand is like a hot coal, Mrs. Lane, and this is not such a very big bowlder. I think we must get a mooshk.”

“What is a mooshk?”

“He is what you ride on. I forget the English word—with long ears and very little feet.”

“A mule?”

“Yes, that is it. We must get a mule for you to ride.”

“Oh, do you think we can? Ask the Shala man if he knows where there is one.”

The Shala man, to my joy—but Rexh looked doubtful—said at once that there was one at the next house. So we went into it, and sat for some time by the fire, and were given coffee, our steaming clothes making the place like a Turkish bath. But there was no mule; the Shala man said we would find one at the next house. The houses were perhaps a quarter of a mile apart here, scattered along the mountain sides above the Lumi Shala, and the Shala man stopped at every one of them. There would be a delirium of struggling up slopes so steep that I could go, as it were, on all fours, without having to admit that my knees were limp, and then of staggering downward, and then an interval of smoke and fire and thick, sweet coffee, and then out into the water again. At last I began really to protest.

“I won’t go into this house,” I said, flatly. “We ought to make forty miles at least before we stop, if we’re to get to Scutari in three days. We have to keep going all the time. I’m not going to stop in any more houses.”

“Mrs. Lane, we have to,” said Rexh.

“But why? It’s nonsense! This man’s saying always that the mule is at the next house. These people know whether there’s a mule in the village or not. We needn’t stop in every house.”

“Yes, we do, Mrs. Lane. We are in Shoshi and this man will be killed if he does not take care. You do not look like a woman, Mrs. Lane. You look like a Montenegrin man, in those pants and that long gray coat. He has to stop in every house, so that the people will see he is traveling with a woman.”

“But, Rexh, I thought we were going through Pultit.”

“This is Shoshi, Mrs. Lane.”

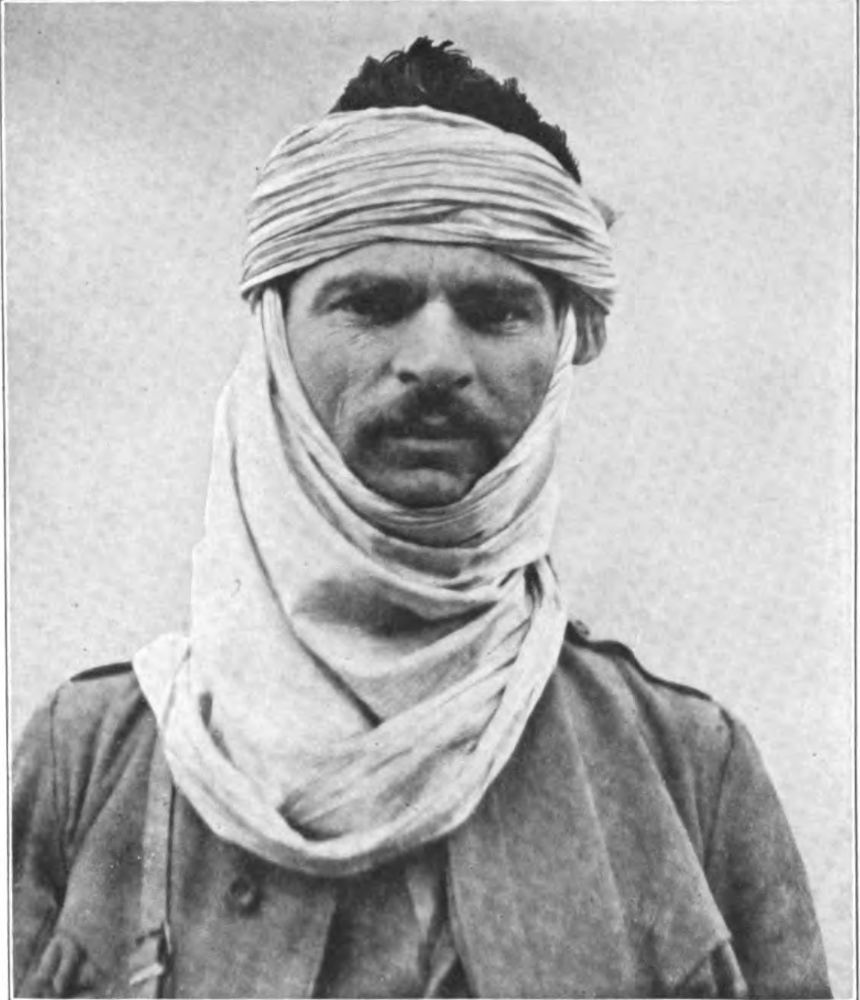

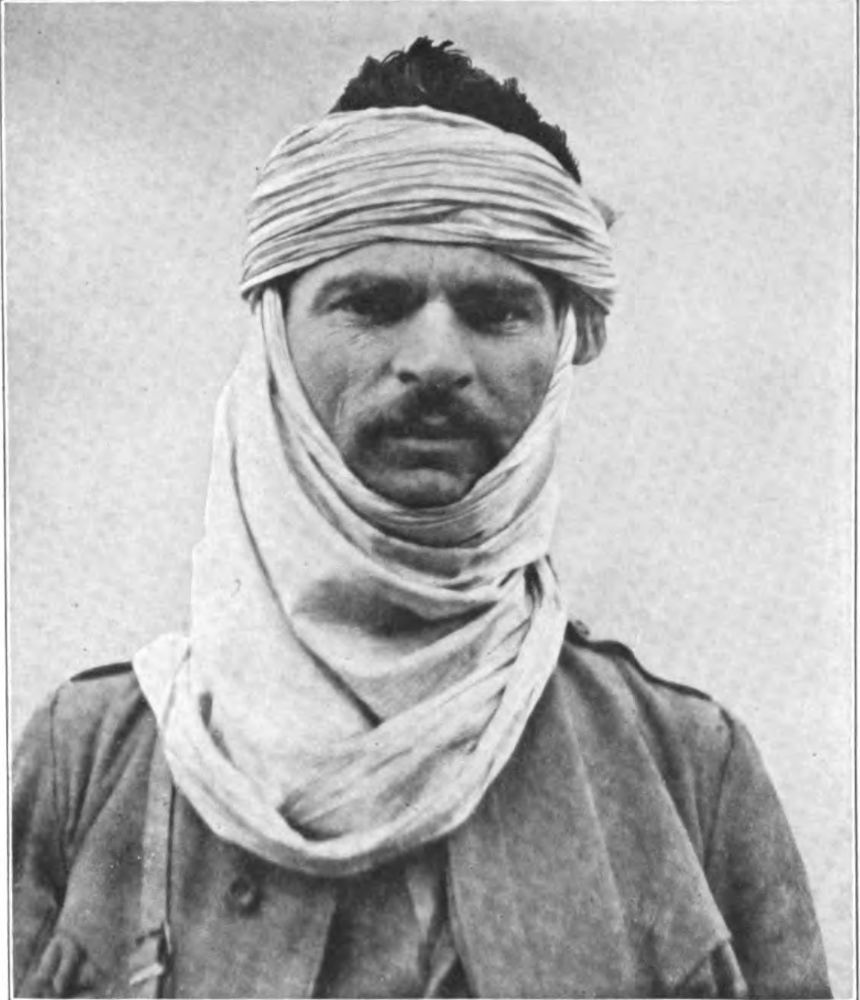

The Shala man, tall and young and very conscious that he was handsome, stood easily on the slope beside us, rain running over him as though he were a stone in a stream, his rifle held carefully protected from the wet by a fold of the poncho. He seemed entirely happy.

“What do you mean,” said I, furiously “by bringing me through Shoshi when you agreed to take me through Pultit?” And when Rexh, like a small image of an accusing judge, had translated, the Shala man looked like an artless child surprised in innocent mischief.

“He says he thought it would be fun. Because they can’t kill him while you’re here, and he likes to go into their houses and drink coffee,” said Rexh.

I sat for some moments on the streaming bowlder, wiping my streaming face now and then with my hand, and staring at that man with the peculiar sense of humor. So he thought it funny, did he, to bring me through a tribe whose rifles were oiled to kill him, and to sit at their firesides, perfectly safe in my protection? Fastened in my own little affairs like a turtle in his shell, I sat there, black with rage, thinking that I would like to murder him, myself. Then suddenly I put out my head and saw the wide world, and the spectacle of us three, dripping there on that immense and drenched landscape in the middle of Albania—the innocent Shala man who had been delightedly thumbing his nose at Shoshi’s warriors, the small, serious Rexh with a map of tiny red rivers over his face, and me, who looked like a Montenegrin man, all of us so intently solemn——

But the vision was disastrous, for laughter set the knives slashing through my lungs again, and I did not know how much of the rain on my face was tears before I was able to speak.

“Tell him I hope he enjoyed the joke, for it’s over,” I said. “You’re Mohammedan, Rexh, and safe; just call to the house and tell them who I am, and ask if they have a mule. And when they ask us in, tell them glory to their house, but I cannot stop; I have made a vow to get to Scutari.”

The Shala man was so downcast at passing one household he could not crow over, that my harshness would have relented under any other circumstances. But I was convinced that I was in for pneumonia, and every impulse in me concentrated in one obsession—to get to Scutari.

“After this, Rexh, you are managing this party,” I said.

“Yes, Mrs. Lane,” said he, toiling up the trail like a small pajama-clad gnome. And with all the sagacity and resource with which he manages his household of younger refugee children in Scutari, he took charge. The clearest picture that remains to me of that day is that of Rexh, his head tipped back and the staff in his left hand firmly planted, while with his right forefinger he sternly laid down the law to a thoroughly cowed Shala man.

THE SHALA GUIDE

Who took the author through Shoshi for a joke

It was Rexh who decreed that he carry the pack, while the Shala man carried me up the worst of the slopes; it was he who sent a man from one of the houses to climb the nearest mountain and call down the valley that we were searching for a mule; it was he who decided when we should stop to eat.

He and the Shala man ate cold meat and corn bread and goat’s-milk cheese, beside a fire on the earth floor of one of the houses, and it was there that a violent-looking man, with a scarred face, clothed in the merest fragments of rags, tried to terrify me into giving him an order on the Red Cross in Scutari for clothes. He was a guest in the house; he had been driven from his own village by the Serbs; his wife and all his children had been killed around him; and I think he was a little mad.

“Give me clothes!” said he, thrusting his horrible face almost against mine, one hand on the wooden-handled knife in his grimy sash. “You Americans have given clothes to others! Give them to me!”

“Tell him that all the American clothes are gone, all of them have been given away, and there are no more. And tell him that in any case I am not of the Red Cross and cannot give him an order. I am very, very sorry.”

“Write! Write me clothes on your pieces of paper!” the man snarled, and if Rexh had not sat so calmly beside me I would have thought he meant to strike me with the knife he drew. The incident was like the horror in a nightmare.

“Tell him I can write on paper,” I said, shrugging, “but the paper will not get him clothes.” So he sat down, muttering. I was glad when Rexh said we would go on, for I did not, like the Shala man, delight in receiving courtesy at the hands of these people who so gladly would have killed him.

We went on over the trails, driven by the unflagging Rexh. His quiet persistency really maddened the Shala man; it was like that of a fly. He drove the Shala man onward without a pause, up and down cliffs, over bridges of logs just missed by roaring cascades, through streams where currents made him stagger. Surely half the time Rexh demanded that the Shala man carry me; the rest of the time the two were pulling me upward, or letting me downward, by both hands, as though I were a bundle. And just as the light was failing we stood on the brink of the most magnificent cañon of which I have ever dreamed.

There were depths below depths of it, falling away from narrow green terrace to terrace, and far down, at the edge of a drop that looked as though it were a crack sheer to the center of the world, there was a stone house. From the other side of the chasm a tilted slab of rock rose up into the clouds—a stupendous great sweep like a wing of the Victory of Samothrace, and it was striped in jagged lines of green and gray and rose and white, hundreds of stripes, each as wide as the stone house down in the blue distance.

We knew it was a large house; we could hardly have seen it if it had been a small one; it looked as large as a match box.

“The byraktor of Shoshi lives there, Mrs. Lane, and I think we had better stay with him to-night,” said Rexh. “There is a priest, but he is four miles farther down the valley, and we would have to come back in the morning, for this is where the trail begins to cross the mountains to Scutari. Also, if there is a mule in Shoshi, the byraktor will know him.”

So we began dropping down to the house, the Shala man much pleased by the adventure of calling upon his enemies’ war chief. We went easily, for the way was a gigantic staircase of cliff and terraced green field. Each field had its little house of stone; the trails down the cliff were broadened and held up by walls of stone. True, the centers of the trails were running ankle deep in water and springs gushed from every wall, but the effect was of ease and order and fresh green things, and before we reached the house of the byraktor my head was clearer and my breath no longer stabbing pains.

How to account for it I do not know; I am sure that in happier conditions I should have had pneumonia. But the fact is that after nearly forty miles of incredibly difficult journeying over those mountains in twelve rain-drenched hours, I came to the byraktor’s fire weak, it is true, and trembling like a convalescent, but with fever gone and my lungs merely aching. I suggest the remedy for what it is worth.

The byraktor received us at his gateway, for his house was surrounded by a high fence, almost a stockade, of woven branches. He was a tall, keen, quick man; bright, dark eyes and aquiline nose and thin, flexible lips, framed by the white turban’s fold beneath his chin; a jacket of black sheep’s wool; one massive jeweled silver chain on his breast. His swift smile was warm and beautiful, but one had a sense of reservations behind it; he welcomed the audacious Shala man without a quiver, and ushered us up the stone steps to the second floor of his house.

There were several rooms, divided from the main large one by partitions of woven willow boughs, and from the large room a high, arched doorway in the stone wall led into farther regions. At least forty men and women and children—five generations—were around the fire on the floor. There was a little flurry of welcome and rearrangement, and in a moment we were in the center of the circle, sitting on thick mats of woven straw, while the byraktor made our coffee in the coals.

The women were beautifully dressed; I had not seen so much elegance of embroidery, of colored headkerchiefs, earrings, and chains of silver and gold coins. Their dark, beautifully modeled faces, large dark eyes, and heavy braids of black hair were set off by the profusion of rich color. Most of them were sitting on low stools, embroidering or working opangi, and the white-garbed men lounged at their feet, closer to the fire, resting on elbows and smoking.

There was the delicate negotiation about the mule. The byraktor owned one, but he did not want to take it to Scutari. I left that to Rexh; the byraktor listened to him as courteously as though the boy had been twenty years older, and Rexh bargained with him as with an equal. A hundred kronen, Rexh said, tentatively, at last, but even at that terrific price the byraktor did not seem eager to make the trip (for, of course, he himself would go where his mule went) and Rexh thought best to drop the question for a while.

“Where do you come from?” one of the youths asked me; and when I had replied, “In what direction from here is America?”

“California, the part of America from which I come,” I answered—and did not very greatly stretch the truth—“is directly through the earth, on the other side.”

Why they sat up in such excitement I did not know; I had expected surprise, but not such a volley of questions, not such a visible sensation. Rexh sat replying to them, earnestly explaining, making a gesture now and then; their eyes followed his hands, fascinated. His talk became a monologue; it went on and on; all work stopped, cigarettes burned to heedless fingers, the coffee bubbled unnoticed by the byraktor. Little Rexh, sitting erect in his pajama coat, the streaks of red dye now dried fantastically on his chubby face, held them all spellbound, while I begged him in vain to tell me what he was saying.

“It is nothing, Mrs. Lane,” he answered me, at last. “I am telling them about the map. I am telling them that the map is not flat, as it looks, but round, like a ball.”

He was telling them that the earth was round! And hearing my voice, they appealed to me in a bombardment of questions.

“Is the earth really round?”

“Yes.”

“You have seen it? You know that it is round?”

“Yes.”

“You have been around it, yourself?”

“Yes,” I said, mendaciously.

They sat back and considered this. Then they asked particulars. They could understand that the earth was curved, for they had seen that the mountains were not flat, so it would be possible for the earth to be curved. But were the seas curved also? Would water curve? I said that it would, that, indeed, it did.

Had I been upon the great spaces of water and seen that they were curved?

I had been upon the seas, I said, and they were curved. They did not look curved, because the earth was so large and the eye saw so little of it, but they were curved, for one could go quite around the earth on them.

They smoked over this for some time. The byraktor rescued his coffee pot, in deep abstraction. I did not expect them to believe what I had said. How could they? It must have appeared to them the wildest of fairy tales (although in all Albania there are no fairies, and therefore—I suppose that is the reason—there are no Albanian fairy tales). Men suffered much at the hands of our ancestors for telling them the monstrous idea that the flat earth is round. I wished I knew what thoughts were taking shape behind those dark Albanian eyes.

Then the byraktor looked up. “If the solid earth is round,” he said, “and if the water lies upon it in a curve, then this earth is moving very rapidly. For if the earth were standing still the water would fall off.”

My astonishment was profound. I felt myself a child beside that mind, and I thought that a man who could so wrestle with a new fact and evolve from it an even more amazing conclusion was no man for me to contend with in a little matter of hiring a mule and getting, somehow, to Scutari.

Presently large flocks of sheep and goats were driven through the room, past the fire, and into the darkness beyond the arched doorway. Rain-drenched shepherdesses, half clad in rags, followed them, and having, with much noise of tearing branches, given them their dried oak boughs to eat during the night, the shepherdesses returned and sat by the fire, addressing the byraktor in tones of accustomed equality.

There was a constant movement in the room—women coming and going, nursing their babies and tucking blankets more tightly over the cradles, undressing the smaller children, who played naked about the fire until they were taken, unprotesting, to their blankets in other rooms, and bringing casks of water, and making corn bread.

One could always amuse the women by asking them about ages; they guessed mine all the way from sixteen to forty, and there was one of them, a splendid, smiling woman, good natured and competent, whose age I guessed to be forty. She laughed aloud, showing all her white, perfect teeth, and said that she was seventy-two, and that the byraktor was her daughter’s son.

“You have been drinking the new water,” she said, wisely, though I had not mentioned the ache of my breathing. “You have the feeling of knives here,” and she touched her chest. “But do not worry; it is all right; it is only the water, and when the rain stops you will not feel them any more.” And she patted my shoulder comfortingly.

The question of the mule still hung unsettled. The byraktor seemed to be thinking deeply; he asked the Shala man many questions about Rrok Perolli. I caught the name and asked Rexh to listen, for I felt myself surrounded by web within web of intrigue, but Rexh said that the Shala man had nothing to tell, except that Perolli was in the mountains. I wondered whether to tell the byraktor that Shala had sworn a besa with the Tirana government, and then thought best not venture into mazes that I did not understand. But the byraktor was greatly interested on learning that I had been in Montenegro, and all that I knew about that part of Jugo-Slavia I told him; it was very little, but he seemed to see more than I did in the robbery of the Serbian Minister of Finance by Montenegrin bandits.

“The story was in the newspapers,” I told him. “Some day there will be newspapers in Albania, and schools in the mountains, and then you will learn about these things when they happen.”

“I have heard about the school in Thethis,” he answered. “Schools are very good, but what my people need is food and clothes. We are very poor. We have too little land. A school is of no use to a child who is hungry, for hunger has no brains with which to learn. I do not care for a school in Shoshi until all my people have enough bread. It is not right to give the well-fed child a school, too; he has already more than other children, and the school will only make him wiser and prouder than the poorer ones. Already the families with fewer children are stronger than those with many, and that is not right. I do not want a school; I want land for my people, for food comes from land, and after food comes the school. There is no hope for the mountain people while enemies hold our valleys. First the Romans, then the Turks, then the Austrians and Italians, and always, always the Serbs! And it may be that the Serbs will be too strong for us and that we shall all die fighting them.”

After that he went to the other side of the fire, beside his grandmother, and he sat for a long time talking to her. “Shkodra,” I heard, which is the Albanian name of Scutari, and “mooshk” and I knew he was talking of me and the mule I wanted to hire, but why it should be such a long and grave discussion I did not understand.

Then we had dinner, served on several little tables, that all might eat at the same time, and the men and women ate together, but only the youngest and most beautiful woman ate at the byraktor’s table, silent and respectful, dipping her long, aristocratic fingers diffidently in the dish. I thought she was his wife, but Rexh said no, she was his son’s bride, still in those six months when she must not speak until spoken to, nor sit unless asked, and the byraktor liked her very much and wished to make her feel at home, because she was lonely for her own tribe.

After we had all washed our hands for the second time, and the men had had an after-dinner smoke—I still turned my head from the proffered cigarettes—the byraktor said that he would himself escort me to-morrow on the road to Scutari. I should ride his mule, and it was arranged that we should start at four o’clock.