POSTSCRIPT

IN WHICH IS RELATED WHAT MAY BE FOUND BEHIND THE CURTAIN OF SILENCE WHICH HIDES ALBANIA, ALSO HOW THE MEN OF DIBRA CAME WITH THEIR RIFLES TO TIRANA, AND HOW AHMET, THE HAWK, CHIEF OF THE MATI AND PRESENT PRIME MINISTER OF ALBANIA, SAVED THE BALKAN EQUILIBRIUM.

For me, there has been a sequel to this tale of my first adventures in the Albanian mountains. And if I have transmitted, through the little clickings of my typewriter, something of the interest and charm those adventures had for me, perhaps there will be interest in the few additional things I have learned about the Albanians.

Just a year from the day on which I parted with the byraktor of Shoshi, I came with a friend, Annette Marquis, down the Adriatic on a Lloyd-Triestino boat to Durazzo. As always, a flock of little boats came out to meet the steamer. Dingy, unpainted, rowed by villainous-looking, swarthy men in rags, they seemed indeed the emissaries of a nation of brigands. The nice girl from Boston, who was traveling from Venice to Athens chaperoned by two aunts, looked at us with horrified eyes.

“You aren’t really going into Albania—all alone?” she gasped. “Why—won’t you be killed?” The shipload of passengers crowded the rail to watch us descend the swaying ladder, and gazed as the safe crowd watches the lion tamer, divided between admiration for daring and contempt for such senseless waste of courage. The weight of this mass opinion swayed even my friend, who said, nervously, as we went bobbing across waves of green water: “I wish I hadn’t listened to you in Budapest. I wish I’d brought the gun they told us to bring.”

“Nonsense!” I said, firmly—and would have believed no fortune teller who had told me I was lying—“we’ll be safer in Albania than in New York.” And with irrational, vicarious pride I pointed out to her the many masts of sunken ships around us—remains of Austrian and Italian cruisers impartially sunk by Albanians during the Great War.

As the boat came nearer to the yellow walls of Durazzo I gazed with complacency on the ruins of the palace of the Prince of Wied, the German king forced on Albania by the European Powers just before the Powers themselves leaped at one another’s throats. In 1914 the Albanians rose and drove him out with their rifles; his palace is a ruin now, and the palace grounds are a public park. But all Durazzo is built upon ruins, for it was an ancient city when the Romans built the towers and walls that still surround it, and there are still cafés on the sites of the cafés where Cicero sat with parchment and stylus, writing home to Rome for money to pay his way back—because, as he admitted with some chagrin, he had wasted all his substance in that merry and wicked city. Even for Cicero Durazzo had, in addition to its living charms, the flavor of antiquity, for the Roman city was built on the ruins of the older Albanian seaport.

A year earlier there had been no automobiles in Albania, but now, to our surprise, we found a valiant small Ford waiting at the pier, and engaged it at once to take us to Tirana, forty miles away. Our baggage was a problem until the chauffeur of a government truck, addressing us in French, volunteered on his own responsibility to take it to the capital for us. “Pay? Mais, non!” said he, hurt. “You are Americans, and the stranger in Albania is our guest.”

The road from Durazzo to Tirana crossed the low mountains that, from Trieste to Valona, make the endless monotonous eastern wall of the Adriatic. When you come over the crest of them you see lying before you the green low central valley and the farther blue peaks of the lands of the hidden tribes. And everything accustomed, everything commonplace, everything that reflects ourselves to us, is left behind. Gray water buffalo, flat-nosed, curly-horned, monstrous beasts that seem risen from depths of primeval slime, plod down the road drawing high, narrow wagons of wickerwork on huge wooden wheels. Shaggy, small donkeys carry picturesque folk down the winding road to Shijak, the village by the river where the bridge begins and ends in willow groves.

Beyond Shijak the road goes over the last low hill, and twenty miles of plain lie before it, most sparsely dotted with the great white houses of the beys of central Albania. Against the eastern sky the towering mountains, with their eternal smoke of clouds, catch the last rays of the sun and make magic with it. For an hour the colors shift and change, plum purple, orange gold, mauve and violet and sea green, until at last only a pale gold moon and a silvery star shine in a lemon-yellow sky. And the seven white minarets of Tirana lift above the green of trees.

Dusk was on the plain, and lights were glimmering through little houses here and there, when we came to Tirana. No, the lights do not glimmer through windows; these houses of peasants on the great estates have no windows, as they have no chimneys. The light of the evening fire, built on the earthen floor, shines through walls woven of willow withes, and the smoke seeps through thatched roofs.

Before us twinkled the street lamps of Tirana. These are literally lamps, filled every day with kerosene and set on their poles, to be lighted with a match after the evening call to prayer from the minarets. Our little car passed between low, ghostly white walls, and stopped before the gendarmerie. An officer came out, lifted one of the street lamps from its pole and held it over the car door, the better to see us.

“Long may you live, zonyas!” said he, and, after he had glanced at our passports: “All honor to you. Go on a smooth trail!” And the words rekindled an old hearth fire in my heart. After a year of the bleakness of Europe, I was at home again.

Three days later rifles were crackling, machine guns were ripping out their staccato shots, and we were under fire in the streets of Tirana. It was the rebellion of March, 1922—a strange affair, which I am about to relate. But before it can be understood, Albania itself must be understood, for that crisis and its outcome are incomprehensible, incredible, without their background.

It would be useless, even though it were not dishonest, to claim that I see Albania with impartial eyes. But this should be said: if I feel a fondness for the little country which perhaps obscures clear judgment, that fondness was created by knowing Albania. I came into it, as I have said, rather prejudiced against it than otherwise. I did not intend to stop there; I was persuaded to stay two weeks; and I have twice returned to Albania and will go there again.

Yes, I have become a special pleader for Albania. But I know the country, I speak the language, I have traveled along the northwestern frontier from Lake Scutari to the Dibra, I have spent months with the people of tribes never before visited by a foreigner. And I have yet to read in any American publication a reference to Albania which is accurate. When a writer so well informed as Mr. Lathrop Stoddard refers to Albania as a “land of rugged mountains and equally rugged mountaineers which raises nothing but trouble,” and thinks that its importance in the Balkan problem is due to Italy’s exaggeration of Valona’s military importance; when all American consuls in Europe warn travelers not to go to Albania, a land of brigands; when Albania appears in the newspapers only as a joke or as the scene of another lawless revolution—the few Americans who know Albania do become special pleaders.

There are good reasons for these misconceptions of Albania. For six centuries the Albanians were one of the buried Christian minorities of the Turkish Empire in Europe. Their great men who rose to places of power in the Near East were not known to the outside world as Albanians. Ismail Kemal Bey, Grand Vizier of Turkey, who raised the flag of Albanian independence in 1912; Mehmet Ali, who led the struggle for Egyptian independence in 1811 and founded the dynasty of the Khedives of Egypt; Crispi, the great Italian statesman—these are a few of the Albanians who, having lost their own country, have fought under other banners. When the Albanians of Sicily rose behind Garibaldi and fought for a free and united Italy, they were thought to be Italians. When the Albanians of Epirus fought for the freedom of Greece, they were thought to be Greek. When they fight for the freedom of Turkey, they are thought to be Turks. And—this is of greater importance—when the Albanians rose to fight for the freedom of Albania, they fought behind a curtain of impenetrable silence.

They were surrounded by a battle line. The Slavs were north and east; the Greeks were south; the Italians were west. Albania was cut off from the outside world in 1910; for thirteen years she has been cut off from the world. No telegraph or telephone lines ran from Albania to Europe; no mail got through without censorship, no traveler without passport visé from enemies. Letters for Europe must still go by messenger through Jugo-Slavia, or by Italian steamer to Italian ports. During May and June, 1922, while I was in Tirana, Albania’s communication with Europe was completely closed by the Italians, in retaliation for Albania’s protest against the establishing of Italian post offices in Albanian cities.

Behind this veil of silence, the truth about Albania lies hidden. Only one newspaper correspondent, to my knowledge, has visited Albania in recent years—Mr. Maurer of the Chicago Post. Mr. Kenneth Roberts of the Saturday Evening Post lay for ten days ill in Tirana, left with all haste for Montenegro, and later wrote of Albania—entertainingly. News of Albania bears the date lines of Belgrade, Rome, Athens. Since 1910 it has been as accurate as news of France bearing a Berlin date line. This is only human, for few of us are accurately just to our enemies, and the Hungarian, Austrian, Serbian, Italian, and Greek soldiers who have campaigned in Albania have returned to describe the country as hell with variations. The one European who has spoken to me of the Albanians without horror is a doctor in Budapest. He had worked in Serbia during the war, and there had encountered a terribly wounded Albanian still alive on a battlefield. The doctor bent over him to examine his wounds, and the Albanian bit off the doctor’s little finger.

“I cannot think of that man without admiration,” said the doctor, looking thoughtfully at his mutilated hand. “I can’t blame him for this; I had not spoken to him, and he thought I was an enemy. He was a splendid fellow—stood the most frightful agony without a murmur, and kept his spirit like a lion. I did what I could for him—had no hope of saving him—and that night, wounded as he was, he got away. I hope he reached home alive. Some day I’m going to see Albania.”

I spoke of Albanians as a Christian minority in the old Turkish Empire. One of the most frequent errors about Albania is the belief that it is Mohammedan; this report has been used for political propaganda. The Albanians became Christians before the Roman conquest, and were Christians when they were subjugated by Turkey. They remained Christian without exception until after the death of George Kastriotes—known in European history by his Turkish name of Iskander Bey Scanderbeg—who successfully revolted against Turkey and maintained Albanian independence for twenty-five years, defeating the Turks in thirteen great battles and innumerable small ones. After his death in 1467 some of the chiefs of the central mountain tribes, exhausted by a quarter century of war and confronting fresh Turkish armies, purchased their actual independence by a verbal submission and became nominally Mohammedan. When the Bechtaski sect—which may roughly be said to bear the relation to Islam that the Methodist bears to the Church of Rome—rose in Turkey, it found its most fertile ground among these Mohammedan Albanians. The northern mountain tribes have always remained Roman Catholic, and southern Albania Greek Catholic.

None of these creeds, however, have affected national unity—Albania is the only Balkan country in which religion and nationality are not synonymous—and all of them are rooted shallowly above the old religion of Albanians, which is the formless belief in a Great Unknown from which sprang the gods and mythology of ancient Greece. In southern Albania you will still hear the people taking oath per kete djelle eghe per kete hene (by the power of the sun and the moon). You will still hear them calling upon Zeus—Zaa or Zee, the Voice—and upon Athena—E Thana, The Intelligence. In the north, the Catholic mountaineer greets the rising sun with the sign of the cross, and hears in his forests the voices of the ora. This vague religion is unconscious. The Albanian himself does not recognize it, but it is the resisting subsoil which has prevented acknowledged religions from taking deep root. Families of all religions freely intermarry; Mohammedan women are unveiled, or Catholic women veiled, according to the fashion of their town; in the mountains neither are veiled. In Guri-Bardhe, a village of the Mati known as being fanatically Mohammedan, the women were quite willing to pose for photographs, and Limoni, the chief, was defying the local hodji by demanding a modern school; the hodji taught the children nothing worth while, he said. In the spring religious festivals—the two Easters and the fast of Ramazan—all Albanians in Tirana took part, and Mohammedan fezzes were thick in the midnight processions carrying Easter candles.

There has never been friction along the frontiers of the three religions. All Albanians united to resist the Romanizing and Germanizing influence of Catholicism, the attempt of Shiek ul Islam to cripple the Albanian language by a Turkish alphabet (a revolution was fought, and won, for the Latin alphabet in 1910), and the Hellenizing propaganda of certain Orthodox Churchmen.

But there is a real division in Albania. It lies between the Toshks, or southerners, and the Ghegs, who are the mountaineers. Men who have held their mountain fastnesses and maintained their independence for six centuries within the Turkish Empire look with distrust and contempt on the Toshks whose valleys have been flooded by every wave of invaders. The Toshks, who are the educated men of Albania, and the travelers, are equally contemptuous of the Ghegs, ignorant men unable to read or write. Nor do the Toshks admit that they cannot fight as well as the Ghegs. It was the Toshks in Sicily who fought with Garibaldi, the Toshks of Egypt who fought with Mehmet Ali; the Albanian soldiers in Russia and Rumania and Turkey are Toshk; the 50,000 Albanians in the United States are Toshk, and fought well with the Americans in France. Hundreds of them have returned to spread American ideas through the south; there are Toshk villages in which American English is spoken by nearly every child. Men from these villagers led the forces that drove the Italians from Valona in 1920. Indeed, say the Toshks, they can fight as well as Ghegs. But it is not fighting that Albania needs.

One of the errors about Albania, to which I fear my descriptions may contribute is the belief that the country is entirely mountainous. This is true of the northern part, adjoining Montenegro. Farther south the ranges are like the partitions in a house; steep, high, almost impassable, they surround valleys and plateaus of rich level land, much of it irrigated. The climate of the valleys is semitropical; rice, cotton, tobacco, citrus fruits, figs, and pomegranates flourish. The southern plains, before the war, exported fine horses in considerable numbers. Properly developed, Albania would be a rich agricultural country, even without the fertile valleys of Kossova and Epirus.

The mineral resources of Albania are unknown. During the Austrian occupation, a survey was made, looking toward the development of copper mines during the war; the results of the survey have vanished into the archives of the Austrian War Department. However, even the untrained eye perceives that there are copper and lead in the mountains. English mining engineers have told me that there are probably also silver and gold. I have seen veins of coal projecting on mountain sides; the mountaineers chip it off with hatchets or pry it loose with levers, and use it as fuel to a small extent. There are millions of feet of pine, oak, birch, and beech timber; unlimited water power. There are oil fields near Valona; producing oil wells were sunk, and later destroyed, by the Italians. Valona’s military importance is not the only reason that Albanians are not left in peace.

There is also the political background. For twenty centuries the Albanians have been a beleaguered remnant of the first Aryan race in Europe. By character, temperament, and choice they belong with the peoples of the west, not with their Slav neighbors in the Balkans. But they have had no friends, either in west or east; their whole history has been a struggle for existence.

A TOSHK

In his native costume of southern Albania.

They were never entirely subjugated by Rome; they were not destroyed or assimilated by the Slavs who have been pushing them southward for sixteen hundred years; they never ceased their resistance to Turkey. Since 169 B.C., when the Romans drove them into the mountains, they have been fighting for a free Albania, and giving the Balkans no peace.

They fight with rifles and with diplomacy. They have had no friends, but they profit by the quarrels of their enemies. Wherever there was a weak place in Asia Minor or Central Europe, there the Albanians have tried to strike a blow for Albania. The opportunity of their hero, Scanderbeg, came in the fifteenth century, when the Sultan of Turkey was killed on the battlefield he had won in Kossova. Scanderbeg, whose childhood and youth had been spent in the Sultan’s court, was left second in command of the Sultan’s victorious forces. He profited by the confusion attending the Sultan’s death to get an order giving him command of the fortress of Kruja, built by his father on a mountain overlooking Tirana. The song says that he killed seven horses in reaching Kruja, leaving his escort far behind in the Mati mountains. When he reached the fortress, he at once proclaimed Albanian freedom, and maintained it for twenty-five years of warfare, during which he built citadels and roads and established laws which still exist. After his death, his people waited four hundred years for another chance to strike. Then the Young Turk movement rose. Albanians seized upon it, precipitated the revolution at Uskub in Kossova, and were the deciding factor in terrifying the Sultan and winning the Constitution which promised to respect the languages and laws of subject peoples in Turkey. When these promises were broken, when Montenegro and Serbia invaded Albania, the chiefs raised the flag of Scanderbeg and wrote their own Constitution of Lushnija. The Six Powers, in an effort to maintain the Balkan equilibrium, gave Albania a German king. As soon as the Powers were engaged in the Great War, Albania drove him out. During the war she impartially fought both sides whenever they invaded Albanian territory. When the war ended, when Jugo-Slavia replaced Austria as Italy’s rival on the Adriatic, and England and France quarreled, Albania played a shrewd game at Versailles and Geneva and became officially an independent republic.

Still blockaded after ten years of war and blockade, still fighting invaders in the Mati and the Dibra, she became an independent republic. Her people, from Hoti and Gruda to Corfu, from the Merdite to the Adriatic, were refugees. Her flocks had been killed, her villages burned, her orchards hacked down, her irrigation systems destroyed. She had a provisional government, hardly strong enough to hold itself together. She could not have a permanent government until her boundaries were fixed by the League of Nations.

She had great natural wealth and no debts, but she had no currency of her own, no banks, no credit system. She had hides, wool, and olive oil to export, but all her frontiers were closed by enemies. She had minerals, forests, water power, oil, harbors, but no machines of any kind, no trained men, no commercial organization. She had the strongest men, the bravest fighters, the most indomitable national spirit in Europe, but few of her people could read or write. Certainly more than half the population was ill from malnutrition and malaria, and she had probably the highest infantile mortality rate in Europe.

This was the new Albania which must somehow maintain itself. And if the curtain of silence behind which this Balkan drama is played were a stone wall shutting out her neighbors, the situation would not be so difficult. But Italy—promised southern Albania by the secret Treaty of London in 1915 which induced her to join the Allies against Germany, and cheated of her payment—has authority from the League of Nations to occupy Albania again if the Albanians fail to maintain a stable government. Serbia is still intriguing to push farther south and west the boundary lines not yet entirely fixed by the League of Nations.

There were other difficulties. Because the Toshks are the Albanians who can read and write, the weak provisional government was Toshk. Around the fires in their mountain houses, the Ghegs were saying that only cowardly Toshks would allow free Albania to bow to a League of Nations—a League of the very Powers who were her enemies. The Ghegs, they said, were no such shameful trucklers. And every fire had its refugee guests who had fled from burning villages, leaving terror and death behind them. These refugees cried to their brother Ghegs for vengeance. Did the Ghegs call themselves men and Albanians? they demanded. “Our teeth in the throats of the Serbs!” the Ghegs replied.

Meanwhile in Tirana the Toshks were talking softly of patience, and of more patience, of waiting month after month for a commission and yet another commission from the League of Nations. The Toshks—with that threat of Italian invasion over them—were demanding peace, peace at any cost. Albania must wait for the League of Nations to fix the boundaries, must acquiesce in any boundaries fixed, must be quiet, must wait.

While they waited, the people starved. Prices in Albania are higher than in the United States—higher in dollars. The homespun garments have worn out; there is nothing to replace them. Fields have been devastated, and no men left alive to till them. Flocks have disappeared, horses and mules are gone. And as the boundaries have been fixed, mile by mile upon a map, Dibra and Mati have lost their market cities, Dukaghini and Merdite have lost their grazing lands, the tribes of Hoti and Gruda and Castrati have been cut in two. Still, the Albanian government spoke of peace, demanded peace, and—determined to have peace—set about disarming the Ghegs in the very face of their enemies.

This was the Albania into whose capital I blithely rode, in the rattling little Ford, on that spring night of 1922. I pass over all the minor political disputes, the ambitions of selfish men, the mistakes of foolish ones, the bitter rivalry between Elbassan, to the south, Scutari, to the north, and Tirana, in the center, for the honor and profit of being Albania’s capital. Tirana was, tentatively, the capital; made so because it was everywhere conceded to be the least progressive, the most hopelessly Mohammedan, the most dangerously un-Albanian city in the country. The government had made Tirana the capital for the same reason that the teacher puts the worst boy of the class in the front seat. But this was no solace to Scutari or Elbassan.

Tirana, the white, low town, drowsed in the sun; water rippled in the gutters of the winding, walled streets; donkeys laden with cedar boughs, the brooms of Tirana, carefully picked their footing on the uneven cobbles; women with gayly painted cradles on their backs trudged behind the donkeys. Men in rags of their homespun white garments and Scanderbeg jackets and colored sashes sat all day on the low walls around the mosques. The fez makers, amid their piles of raw wool and mixing bowls and heating irons, were talking politics, and so were the men in the street of the coppersmiths, which is musical from day to sunset with the sound of little hammers beating glowing sheets of metal. At noon the hodjis droned their long prayers to Allah from the minarets. At sunset their voices wailed again, above the sound of clattering hoofs and tinkling bells as the flocks came home to the courtyards. Then the sunset left a yellow sky behind the dark blue mountains. The air was so still that the bells of a mule train, winding down to Tirana on the far-off foothill trails, chimed with the sound of running water in the gutters beside the courtyards’ mud-brick walls. And the Cabinet Ministers of Albania came out to walk.

They walked in a row, sedately, hands behind their backs, and after them marched their escort, a single row of soldiers. They walked down from Government House, the square two-storied building behind a half-ruined wall; they walked past the Tirana Vocational School and, turning in front of the painted mosque, by the two Cypresses of the Dead, they went past the block of little shops that is Main Street, past the cemetery filled with toppling turbaned stones, past the large white barracks where soldiers sang of Lec i Madhe, and out on the Durazzo road. Then they came slowly back, and slowly went out again. With them on this same way walked all the men of Tirana, for this is the custom at the sunset hour. And we walked, too, saying at intervals: “Long may you live! Long may you live!”

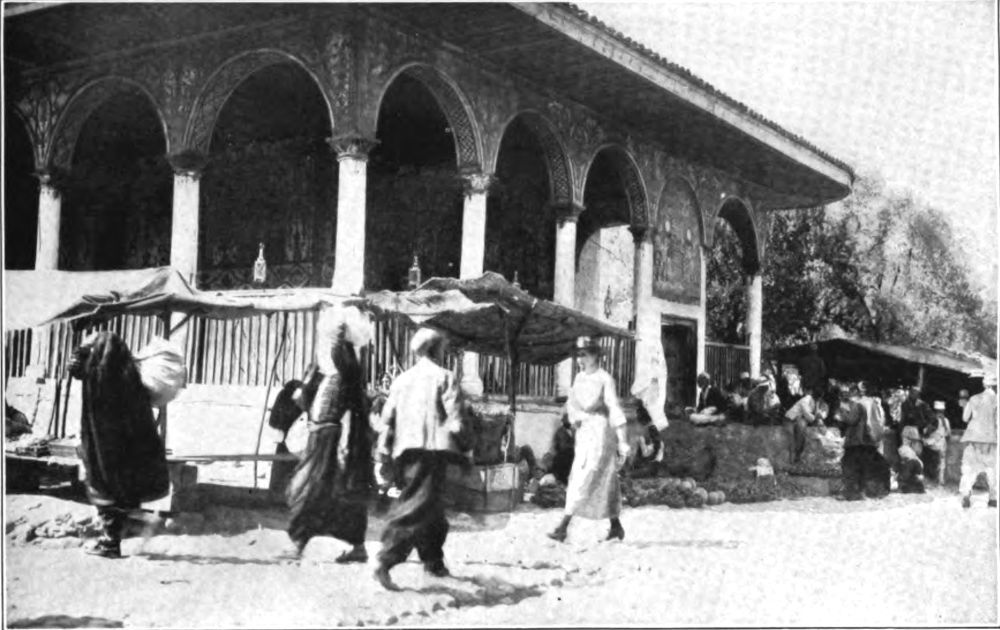

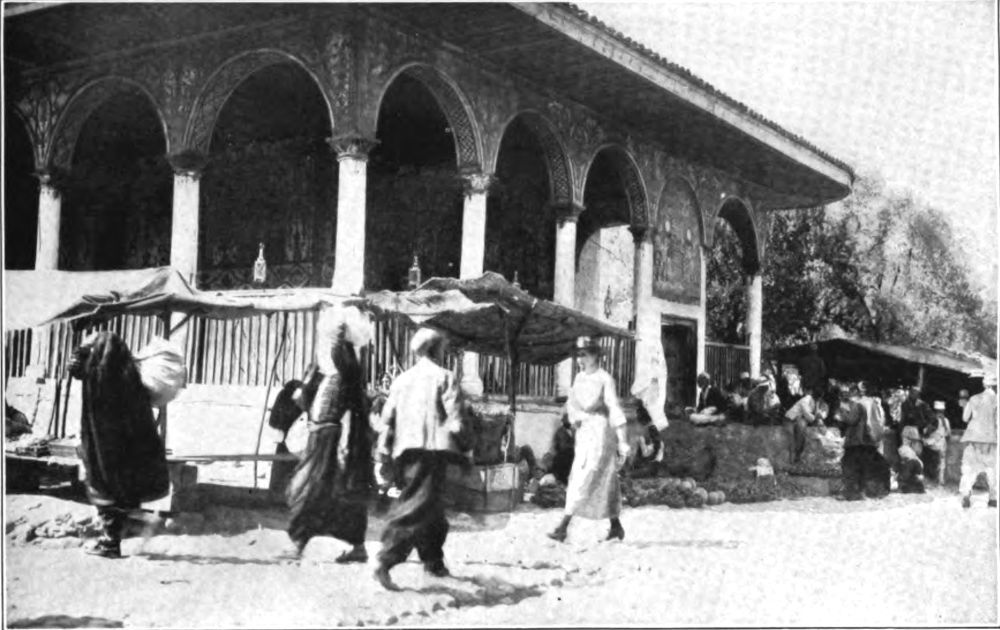

THE PAINTED MOSQUE IN TIRANA, AND THE LOW WALL ON WHICH, ALL DAY LONG, MEN SIT AND DISCUSS POLITICS

It was on the second evening of our walking that, counting Their Excellencies as they came toward us, I said: “Where is the other one? Who is he?” For we had met them all except the Minister of the Interior, and suddenly I realized that he was unknown to us. And Rrok Perolli, who, strangely, was no longer with the government, nor talking much of politics, but living quietly upon an inherited income in Tirana, replied, “He is Ahmet Bey Mati.”

The name awakened a thin, faint echo in my mind, an echo mixed with a remembered sound of rain. But, “Long may you live!” I said to Their Excellencies, and for a moment we stood talking in French.

“The disarming is going well in the mountains, Your Excellency?”

“Very well, very well. No trouble at all. Tout est tranquil, madame.”

I did not believe this, knowing that to a Gheg his rifle was his honor, and either dearer than life. But there is a convention which exempts the words of statesmen from measurement by the Decalogue.

“Then we can soon be starting for the mountains?”

“Certainly, certainly, madame. As soon as we can find proper guides and horses for you.”

We thanked them and, refusing a coffee, walked slowly on in the summer evening. Nothing could have been more tranquil than the low white town, with its cobbled winding streets, its stream murmuring beneath a stone bridge, its minarets, its plane trees. The crowds went slowly up and down, sauntering past the mosque’s naïvely pictured walls, past the white-arcaded street of little shops whose owners sat crosslegged among their goods, past the cemetery of toppling turbaned gravestones, past the lighted windows of the cafés where men were singing the strange Albanian melodies. It is a town to be happy in, Tirana.

But the water rippling in the gutters stirred uneasiness in my mind, a vague uneasy effort, out of which came a name. “Ahmet Bey Mati! What have I heard about him, Rexh?”

“I don’t know all you can have heard about him, Mrs. Lane. But you remember the comitadj, in the cave above the Lumi Shala on the trail from Thethis? The one that sang us the songs? He told you first about Ahmet Bey and how they went to Valona.”

“Oh, Rexh, sure enough! Doesn’t it seem a long time ago? And how you have grown, and how much you have learned, since then!”

For the little boy who trudged beside the donkey through that moonlit night on the plains of Scutari was gone. The red fez, the flannelette pajamas, were memories. It was a youth with a quick smile and earnest eyes who walked beside me in Tirana, a student in the Vocational School, learned in baseball and college yells and geometry, modest still, and thinking more than he spoke, but no longer a child. It was Frances—now in France—who had got Rexh into the American school, handicapped though he was with lack of schooling and with his Gheg tongue, and he had worked hard to justify her commendation.

“I do my best, Mrs. Lane. At first I was very stupid, for I could not understand the Toshk boys, and I could not understand the teachers when they asked me questions, and I was two years behind with the books. But now they speak English, and I have learned Toshk. So I am happy, and my report card is very good. I would like to show you my next one. Now that you have come, I have some one to show it to. It is a joke on me, because, though you said you would come back, I did not think you ever would. And aren’t you happy to find the school really here?”

For we had talked a great deal about the school, a year before when it was only a plan and a hope. Of all the work done by American children in Europe, this school is most beautiful to me. It was not much the Junior Red Cross did in Albania—only a few months of Frances Hardy’s house for refugee children in Scutari, only a little medical work that stopped too soon—but it did build the Vocational School, and Albania will never forget it. Half of the country’s little income goes for the 1,100 schools started since 1912, but none of them can be equipped or staffed like the Vocational School. It opened in July, with sixty boys to learn English. For there are no technical books written in Albanian, and Albanian was the only language the boys knew. Three months later they were speaking, reading, and writing English, and the first school year began. In March, when we came to Tirana, they were the finest upstanding lot of youngsters that ever made a teacher proud, and our arrival was celebrated by an evening’s entertainment, for which the boys extemporised little plays in English, political parodies so witty that they brought tears of mirth to the eyes. I do not think the record of those boys is equaled anywhere, and to find Rexh among them was the happy ending to the story.

“And now Ahmet Bey is Minister of the Interior! Who is chief of the Mati, then?”

“His mother is chief when he is away, Mrs. Lane.”

“Is he a good Minister of the Interior?”

“He works very hard. I think he did not have much schooling. He came from the court of Abdul Hamid when he was sixteen—you remember the comitadj told you—and he has been fighting ever since. He came to Tirana last December when there was the strike.”

“No, Rexh! A strike? In Tirana?”

“It is a long story, Mrs. Lane. If you would have a coffee with me, I would tell it all.”

We left the others wandering down the Durazzo road and back, and sat at a little table beneath a plane tree by the white arches of the café. A waiter brought us cups of Turkish coffee, and while the crowd went slowly past us and bursts of Albanian song came through the open windows and a great yellow moon rose behind the white minaret, Rexh told the tale of the first strike in Albanian history.

“It was at the time of the Merdite trouble. I do not know what you have heard of the Republic of the Merdite; it was a Serbian plan to get the Merdite country. The people were starving, and the Serbs promised them corn, and I think there was money for the Merdite chiefs, because some of them signed a paper that said there was a Republic of the Merdite and the Serbs sent that paper to Europe. Then other chiefs fought these chiefs that signed it, and the Serbs came in, and Ahmet Bey Mati was sent with our soldiers to fight the Serbs. It is five days to the Merdite, when the trails are good.

“You know, Mrs. Lane, Albania has no king. We have four regents, that we call quarter-kings. We laugh when we say it. ‘There goes a quarter-king,’ we say. There are the Ministers elected by Parliament, and their chief, the Prime Minister; they are the real kings. They do things, and then afterward the quarter-kings have to say, ‘Yes, that is what we would have done.’

“While Ahmet Bey was gone to the Merdite with all our soldiers, there were only three quarter-kings in Tirana. One was gone to Geneva; he was a good one. One that was here was a good one. One was a friend of Castoldi, the Italian. No good Albanian, Mrs. Lane, is a friend of Italy. And the last quarter-king, he was from Dibra, and wanted to fight the Serbs.

“And while there were no soldiers here, secretly at midnight thirty men with rifles came into Tirana, and went to the house of Pandeli Evangeli, the Prime Minister. They went in over the walls and through the windows. They pointed their rifles at Pandeli and said, ‘Resign.’ So he resigned. Then he called for a horse and went home to Valona.

“In the morning there was no Prime Minister. And Parliament was not in session. Do you understand, Mrs. Lane?”

I understood. Thus easily—if surmise could be believed—Italy had captured the Albanian government. Two of the three quarter-kings controlled the situation, and one of them was a Gheg. If he were given his head, Italy had only to await the outbreak of violence between the chiefs who wanted war on Serbia and those who were clamoring for peace, and then march in with her authority from the League of Nations to bring law and order into lawless Albania. “What happened, Rexh?”

“But you have guessed it. The one good quarter-king could do nothing, and resigned. The other two made a government to fight Serbia. Hassan Prishtini of Kossova was the new Prime Minister. Then all Albania was like a nest of hornets stirred with a stick. The men of Parliament went riding from their villages to Elbassan, and Prishtini sent word to Elbassan to kill them. Then all the men of Korcha went with rifles to Elbassan to fight for Parliament. Troops with machine guns were coming from Scutari to fight Prishtini. And, Mrs. Lane, there was an Italian gunboat at Durazzo. Everywhere all men, Toshks and Ghegs, were saying, what could they do to save the Constitution? But no one knew how to do it.

“Hassan Prishtini said, ‘The Constitution does not make Albania free; we will make Albania really free. Albanians are not cowards and will not be ruled by cowards,’ Hassan Prishtini said. ‘We have nothing to do with Leagues of Nations that have sold us. We will fight the Serbs and make Kossova free; we will take back our lands of Hoti and Gruda and Castrati. The Italians do not dare touch us. We drove them once from Valona; we can do it twice.’ That was what Hassan Prishtini said.

“‘I think this will be a good year for pears,’ said the bear. ‘Why?’ said the other bear. And the first bear replied, ‘Because I like them.’

“I forgot, Mrs. Lane, that people do not talk that way in English. I forgot I was not talking in Albanian. In English you would say it: Hassan Prishtini thought that he could do what he wanted to do because he wanted to do it. But that is not thinking.

“That very first morning, there was the strike. The two men that can make the telephone work, and the man that clicks the telegraph, and the chauffeur of the government automobile, and the cook and the coffee maker of Government House, and the guard at the door, and all the secretaries of all the Ministers—they all went to the Café International, and had a meeting. Then they walked from the café to Government House and back, singing the song of free Albania. After that they did nothing. They sat and drank coffee. I do not know if you have ever seen a strike, but that is what it is. They did not do anything, and there was no telephone, no telegraph, no messenger, no coffee, nothing at all, for the new government.

“And Hassan Prishtini could not do anything. The new government sat in Government House. Everybody else sat in the cafés. Elbassan did not fight Parliament, because it could not get Tirana on the telephone. Hassan Prishtini’s men in the mountains did not march anywhere, because no orders came. All Albania thought something terrible was happening in Tirana, and wasn’t it funny? Because nothing at all was happening.

“On the third day, Ahmet Bey came with twelve hundred fighting men of the Mati—Catholics, from northern Mati. They came in, and they did not do anything. But there were no other fighting men in Tirana. So Hassan Prishtini resigned, and when the Parliament came to Tirana it made a new government, and Ahmet Bey Mati was Minister of the Interior. And that was the end of the strike. There are songs about it, Mrs. Lane, if you want me to get them for you.”

It seemed to me the most remarkable tale of a political crisis that I had ever heard, and for some time I considered it in silence, getting the full delightful flavor of it. The moon and the minaret were a Japanese print against the turquoise sky, and somewhere a mandolin tinkled and a voice sang the “Mountain Song”:

“How beautiful is the month of May,

When we go with the flocks to the mountains!”

Then a discrepancy in Rexh’s story struck me. “If the Merdite is five days from Tirana, and Ahmet was fighting the Serbs there, how did he come to Tirana in three days? How did he know there was trouble in Tirana?”

“Ahmet is a Gheg, Mrs. Lane. A Gheg always expects trouble. When he went into the mountains he left behind him men he could trust, hidden in the woods by the telephone wires. There is a small round black thing that can hear on a telephone wire—I do not know what you call it. It is small, and has a wire that goes over the telephone wire; you put it to your ear. Ahmet had got some of those from Vienna, and some little mirrors, for the men he left behind him. In the morning after Pandeli resigned, word went over the telephone to Elbassan to kill the Parliament, and to some of Hassan Prishtini’s men to stay on the trails to the Merdite and not let Ahmet get back to Tirana. Ahmet’s men heard this, and with the little mirrors in the sunshine they telegraphed it to the mountains, and other men telephoned it with their voices to Ahmet. So he came secretly around Prishtini’s men, and came walking day and night to Tirana. He left his men in the Merdite to hold the Serbs, and took the twelve hundred fresh men from the Catholic part of the Mati.”

“Ahmet is Mohammedan?”

“Yes, Mrs. Lane. His family has been Mohammedan since Scanderbeg died.”

“In the morning I shall go to see Ahmet. He must be a remarkable man.”

Rexh considered this statement. “He is a good man, yes. We have a saying in the mountains, Mrs. Lane. ‘Ask a thousand men, then follow your own advice.’ I think that is what Ahmet does.”

I had interviewed, without exceptional enthusiasm, each member of the Albanian Cabinet save Ahmet, the Hawk, chief of the Mati. But I am not, in general, enthusiastic about the Ministers or members of Parliament that I have met in any country. In democratic countries their profession gives their minds a remarkable agility, like that of the elephant on the rolling ball. The muscular development of the elephant a-pilin’ teak in the slushy mushy creek has more interest for me. This is a matter of personal taste. However, I am about to become so enthusiastic about Ahmet Bey Mati that it seems well to mention that my enthusiasms are few, and not excited either by statesmen or soldiers. Perhaps six scientists and business men are my heroes. Why, then, after three minutes of talk with Ahmet Bey Mati, did I add to that short list this mountain chief of semisavage tribes, who certainly knew nothing either of science or of modern business?

Government House in Tirana is an old residence, hurriedly converted into offices. It stands at the end of a street, in a courtyard surrounded by a high mud-brick wall rather badly broken at intervals. A mountain man with a rifle sits at the big gate. Another guard, even more gorgeous in white wool, scarlet jacket, and gold embroidery, stands on the wooden porch. Inside, the bare wooden floors, partitions, and stairways suggest a Middle Western American barn. Parliament Hall is furnished with school desks for the members, and a red-covered dais for the President, with the Scanderbeg flag above it, are bright colors against whitewashed walls. The offices are nondescript with overstuffed Italian furniture and fine Albanian rugs. Cigarettes are on the desks, coffee is served to callers, and my feminine experience of interviews was that facts must be fought for against a barrage of French compliments.

We had been in Tirana two days and could not put a finger on any fact to account for the distinct uneasiness we felt. We were tormented by a wholly irrational feeling that, somehow, somewhere, something was wrong. Everything we could see appeared to be all right, everyone assured us that everything was all right. I went into Ahmet Bey’s office prepared to exchange the elaborate forms of mountain courtesy and to look at Ahmet, no more.

The office was bare. No overstuffed furniture, no rugs. Bare floor, bare walls, an unpainted wooden table, and Ahmet. He was keen, self-controlled, hard willed. That was the first impression. The second was that he was the best-dressed man, in a European sense, that I had seen for a long time. He was dressed like the successful American business man who gives carte blanche to a very good tailor and forgets clothes. He rose, said, “Tu njet jeta” (“I am glad you have come”), and while he said it he looked at me as a scientist looks at a microscope slide. Then he offered me a chair, sat down, and added, “Can I be of service to you, madame?”

The shock was such that my mind blinked. Then I said that I wished to visit Mati and the Merdite, and had come to the Ministry of the Interior to arrange for the trip. Ahmet offered me a cigarette, and lighted it, and my mind waked to alertness, for I saw that he was making time in which to choose his reply. There was something wrong; our feeling was right! I would trip him into giving me a clew.

Our eyes met as I thanked him for the cigarette, and I saw that he saw that I knew he had been hesitating. Idiot that I was, to betray it, I thought. And he said, “This is a difficult time in Albania, madame. I cannot tell you whether you can go to the mountains or not. I cannot discuss our difficulties with you to-day. In ten days’ time they will be ended. I must ask you to wait ten days, perhaps less, certainly no more. Then if you can come to see me again, I will tell you anything you want to know. If it is possible for you to go into the mountains, of course you will go as guest of the Albanian government.”

Everything had been said. He accompanied me to the door, said: “Long may you live! Go on a smooth trail!” and held the door open, simultaneously for me to go out and for the next caller to come in. The door shut. And I said, “That is one of the few great men I have met.”

All that day, at intervals, I recalled that interview and marveled. How had that man come from his background? From the leisurely, evasive, allusive talks of the mountains, from the intricate subtleties of Abdul Hamid’s court, where had he got that incisiveness, that direct, driving force? It was genius, I said; nothing less. I went about asking, “Is Ahmet Bey a patriot?” For if he were not, certainly he was one of the most dangerous men in Albania.

I was told that he was a nephew of Essad Pasha, who sold Albania to Serbia for the title of its king, and was assassinated by Albanians in Paris. I was told that Ahmet had sold timber rights in the Mati to Italians, but had later revoked the sale. I was told that he was a very rich man, and that he held the forty thousand fighting men of the Mati in his hand. I was told that the Serbs, in one of their 1921 raids, had burned the Great House in the Mati, the house in which his family had lived for five centuries. Nothing else, apparently, was known about him.

Walking that night at sunset time with all Tirana, we were surprised to observe that the soldiers lounging around the fires in the courtyard of their barracks were not the same soldiers who had been there the night before. These were new men, recruits, and—by the pattern of their trousers—men from the plains of the south. Raw peasant youths, they looked. None of them carried rifles on their backs, and the few rifles we saw were held awkwardly, as by unpracticed hands. Of course there is a constant flow of recruits through Tirana, for as the government disarms the mountaineers it endeavors to build up a trained citizen army, on the Swiss plan. But we guessed, by the absence of the seasoned soldiers, that there was battle, or danger of battle, somewhere else in Albania.

Incredible, as we walked homeward under the white moon, that on this spring night men could be killing one another. Incredible, in this magic of moon and rippling water and a little owl calling love notes from the dark cypress, that anywhere there was anything but peace. The tall carved wooden gate of our courtyard was romantic in the shadow of Government House; our little house was picturesque with black shadows on white plaster; there was glamour everywhere.

“What’s that? Is that a mouse?” said Annette, through the darkness in which we lay awake, watching the moonlight on the walls and breathing the sweet spring air. We listened. Nothing. “I thought I heard something—a sort of little crackling sound.”

“Listen,” I said, half an hour later. “What is that throbbing?”

Curiosity’s nagging at last got us from our beds. Kimono clad and in slippers we went out into our courtyard. The throbbing came from an engine; the engine that feeds the dynamo of Government House. Every window blazed electric light. We looked at them in amazement; we looked at our wrist watches under the moon. Ten o’clock. And we started when the shadow of the wall beside us moved and spoke. “Long may you live, zonyas! It will be very good if you go into your house.”

“Por hene asht shum i mire” (“But the moonlight is very good, too”), I objected, and saw the moonlight glint on a rifle barrel. “Why is Government House lighted? And why are you in our courtyard?”

“There are orders,” the man replied. “Ahmet Bey Mati has spoken. The American zonyas will go into their house.”

He would say nothing more, and there seemed indeed nothing else to do, so we went. The sound that lifted us from our pillows once more was one that I shall not forget, nor willingly hear again. It came through the night like a supernatural thing of hate and fury and irresistible power. We did not know what it was; we had no power to wonder what it was; we heard it with an agony of fear, involuntary, uncontrollable as the pain of a stripped nerve. I remember now that instant and eternity of time, and cannot bear the memory. I had not known that even in nightmare one could drop into such abysses of the human spirit. Then Tirana seemed to explode like a bunch of giant firecrackers, and with such relief as I cannot describe I cried: “Rifles! They’re taking Tirana!” And we tumbled out of our beds and grasped wildly in the darkness for our clothes.

Rifles are human possessions; rifles are solid things that at worst can only kill. The sound of the rifles, multiplied a thousand times by echoing courtyard walls, muffled and enabled us to bear that other sound, still faintly heard through the uproar. “It’s only their war cry,” we babbled to each other. “It’s the mountain men fighting. That’s all it is.” Coherence came back to our minds. “It’s the Dibra,” I said. “Dibra and the refugee Kossova men, come to take the government away from the Toshks.” And we ran out into the courtyard.

The rest of that night was anticlimax. Bafflement. Weary and chilly, we came back to our house at three o’clock. We had explored the courtyard, finding only that the shadows were full of silent, waiting men. They spoke little; they said, in reply to our questions, that they did not know what was happening. We had ventured out of the courtyard into Tirana, that low white town that, to the eye, seemed sleeping in the moonlight, and to the ear was bedlam. Bullets were whizzing, scattering white plaster, smashing tiles. But mosques and minarets, arcaded streets, arched stone bridge, rippling water, were peaceful in the moonlight. No human being seemed to be abroad, save us two, who wandered like forsaken ghosts through the incredible clamor.

The windows of the Vocational School were alight, the American flag was over the gate. We found the Americans making ready a midnight luncheon in the kitchen, whose windows were barricaded against bullets. Great Scott! they said, why hadn’t we stayed in bed? Have some baked beans? We ate the beans and explained that we wanted to know what was happening. Who knew what was happening, in Albania? said they, yawning. Better go home to bed; time enough to find out in the morning what was happening. So, weary and chilly, we went home to bed. The rifles were still crackling like madly popping corn, tiles were still crashing from roofs and plaster from walls, but the war cries were still. We slept fitfully.

A tapping on our window sill roused us again. The moonlight was gone from our wall, the open window was a square of paler darkness in the darkness. “I beg your pardon, I sincerely beg your pardon,” said a voice in French. “This is most unconventional, I know. But if you will pardon the lateness of the hour, may I ask you to permit us to call?” It was the voice of His Excellency Spiro Koleka, Minister of Public Works.

He came in, accompanied by the secretary of the Prime Minister. We sat up in our beds, coats around our shoulders, and told them where to find chairs and cigarettes. They said that if we did not mind they would not light the lamp. We asked what had occurred.

“Rien, rien du tout, mesdames,” said the Minister of Public Works. “Tout est tranquil.”

“The ancient Greeks had a saying,” began the secretary, gave us that saying in Greek, and continued to speak for some time, not uninterestingly, of Greek and other philosophers. The social tone of that early morning call was impeccable. Good breeding required that we maintain it. We sat exasperated in the dark, saying to ourselves that we would gladly murder these two uncommunicative men. But we felt that to ask them to leave the shelter of our house would be murder, in cold fact. In the wan daylight of six o’clock they thanked us for our hospitality, and went.

Tirana was peaceful in the morning sunlight. Donkeys laden with cedar boughs picked their footing on the uneven cobbles; women with gayly painted cradles on their backs trudged behind the donkeys. Ducks were swimming in the brimming gutters. Rrok Perolli stood in the doorway of the Hotel Europa, enjoying the spring air.

Elez Jusuf, chief of the Dibra, with five hundred men, had fought his way into Tirana, he said. The Albanian government had—well, had gone to Elbassan. Elez Jusuf was intrenched in the quarter beyond the mosque, a maze of houses and walled yards entered by only two streets. For reasons unknown, he had not walked on into Government House.

“Ahmet has gone to Elbassan?” The dismay of my voice surprised me.

No, he was still in Tirana. He was legally, in fact, the government; by law, when a Minister was out of town his duties fell to one of the Ministers remaining. Ahmet was the only one left, except the necessarily idle Minister of Public Works. But what could he do? Elez Jusuf was in the capital, with five hundred fighting men of the Dibra. Ahmet had less than two hundred men, raw recruits from the peasant village of the south. And more information came now from the open door of reticence. Two days before, Byram Gjuri, an Albanian Gheg chief of tribes in Montenegro, who had been supplied with arms from D’Annunzio in Fiume, had marched on Scutari. Scutari had sent him word that it would fight, and had frantically appealed to Tirana for help. That was where the regular troops of Tirana had gone. The telephone line to Scutari was cut. There had been an attack from the Dibra on Elbassan; the fighting men of Elbassan had beaten it off, but they were staying in Elbassan through this trouble.

On the face of it, the thing was organized—organized, and supplied with arms and money from outside Albania. Obviously, the capital was lost. The government had fled. The telephone lines were cut. Albania had been broken into its diverse tribes again, disintegrated into particles held together only by a common spirit which could no longer express itself coherently. After all the years of fighting and blockade, all the desperate triumphs of diplomacy in Versailles and Geneva, here was chaos again, and fresh invaders.

This tragedy was behind the curtain of silence that isolates Albania from the world. It went on in darkness, unknown. It meant another war in the Balkans, the kindler of wars in Europe. All along a thousand miles of new frontier and ancient hatred any outbreak in the Balkans would spread. Italy would cross the Adriatic again; what would Jugo-Slavia say to that? Serbia would come down in force from the north; would Croatia, Bosnia, Dalmatia, Montenegro, not seize the opportunity to strike at Serbia, the hated new master? Could Jugo-Slavia turn her back on Hungary, in safety? All the Balkans and Central Europe are tinder to any spark, to-day. As they were in 1914.

But at that moment I was caring for Albania, for the Albanians who had sheltered me by their fires and divided with me their corn bread and goat’s-milk cheese. It was insupportable to me that war was going again like a flame over those mountain villages, that the last of their men must fight again on the edge of precipices, and the last of their women and children die on the trails. There was desperation in the hope, the irrational faith, which I placed in Ahmet, the Hawk, chief of the Mati. “Ahmet will do something,” I said.

“How can he? The Dibra men are in Tirana, and he has no soldiers.”

“He will do something,” I said, “because he must.”

“‘I think this will be a good year for pears,’ said the bear. ‘Why?’ said the other bear. And the first bear replied, ‘Because I like them.’”

“And who knows,” said I with violence, “that it isn’t a good year for pears?”

Thus we talked in the cafés, drinking coffee and looking out through white arches at the plane trees and the donkeys patiently trudging by. There was nothing else to do. Elez Jusuf was in Tirana, behind enigmatic walls. Why did he not come out? We did not know. Ahmet was alone in Government House. The sunshine was warm on white Tirana, the water rippled in the gutters, the plane trees unfolded their tiny leaves. The men of Tirana, that lukewarm, Mohammedan, un-Albanian city, did nothing. They waited to see what would happen. We all waited. The morning went by.

The morning went very slowly by, and at noon an automobile came roaring and shaking down the cobbled street. It brought Harry Charles Augustus Eyres, British minister to Albania. We lunched with him at the Red Cross house. Lean, dry, humorous eyed, gray haired, wholly the Englishman, he talked of the psychology of Eastern peoples. He had been forty years a diplomat in the Near East, and knew his subject. I was perhaps wrong in connecting his official presence in Albania with the Anglo-Persian Oil Company’s negotiations for the Valona oil fields. He lived in Durazzo, and had that morning received a telephone message—not from Ahmet—advising him of the situation in Tirana.

“I must go and see my old friend Elez,” he said. It was his only reference to the immediate situation. “Elez is a fine old chap, you know. Patriotic Albanian. He had five thousand Dibra men ready to go into Serbia last year. Bit of a job I had, too, persuading him that it wasn’t done, really.”

After luncheon he departed, to see his old friend Elez. Later he was seen riding to Government House. At dinner he said that negotiations were opened. One inferred that this little matter was practically settled.

“Queer thing, you know, this tale of Elez Jusuf’s,” he further remarked. Elez Jusuf, it appeared, said that he was astounded to find himself in the position of a rebel against the Albanian government. With the mildest intentions, he had been coming down to Tirana to speak with that government. Parliament had been elected when the Serbs were holding all of Dibra; the Dibra representatives had been elected by refugees, and Parliament had recently unseated them on the ground that they were not properly elected. This left Dibra without representation in the council of chiefs, said Elez. Surely it was proper that the chief of the Dibra should come to Tirana to speak for Dibra to the government. He traveled with an armed escort, of course, as a chief should. On the trail he met his friends Zija Dibra and Mustapha Kruja, with their escorts. They came on together. An hour from Tirana, on the previous evening, they had met a body of government soldiers, sixty in number. These soldiers had treacherously fired upon him. His men had naturally returned the fire. The captain of the soldiers was killed, the second in command, Sied Bey, fell down a cliff when his horse was shot beneath him, and Elez Jusuf, very much surprised and perturbed, came on to Tirana. He said he did not know what else to do. Just before reaching Tirana, he had met a machine gun or two, and had taken them along with him, after some incidental fighting. Why was the government attacking him with machine guns? he demanded. He was not moving against the government, with five hundred men. When the Dibra moved, it put five thousand fighting men on the trails.

“A queer tale,” said Mr. Eyres. “I don’t know what to make of it. On my life, I believe the old fellow’s sincere.”

The Albanians, he said, were a surprising people. Take Ahmet, now. That afternoon Ahmet had said to him, “You recall the words of Aristides?” Mr. Eyres, supposing the reference was to some Albanian unknown to him, had inquired, “Who is Aristides?” And, by Jove! the chap meant the Greek! Fancy an Albanian knowing about Aristides!

We slept upon these meager developments. Elez Jusuf was still in Tirana; Ahmet still in Government House. The dynamo ran all night.

Next morning, more news in the cafés. Ahmet was demanding that Elez Jusuf give up his arms and surrender himself, Mustapha Kruja, and Zija Dibra for trial. Elez Jusuf replied that it was an insult to suggest that any Dibra man gave up his rifle while he lived. If Mati thought it could bring that shame upon the Dibra, the rifles of Dibra would finish the talking. Mustapha Kruja had disappeared in the night; his men were left leaderless with Elez behind the barricades. Zija Dibra was still there. Mustapha Kruja and Zija Dibra were in the pay of Italy; Elez Jusuf had been misled, tricked, by them. This was the talk in the cafés.

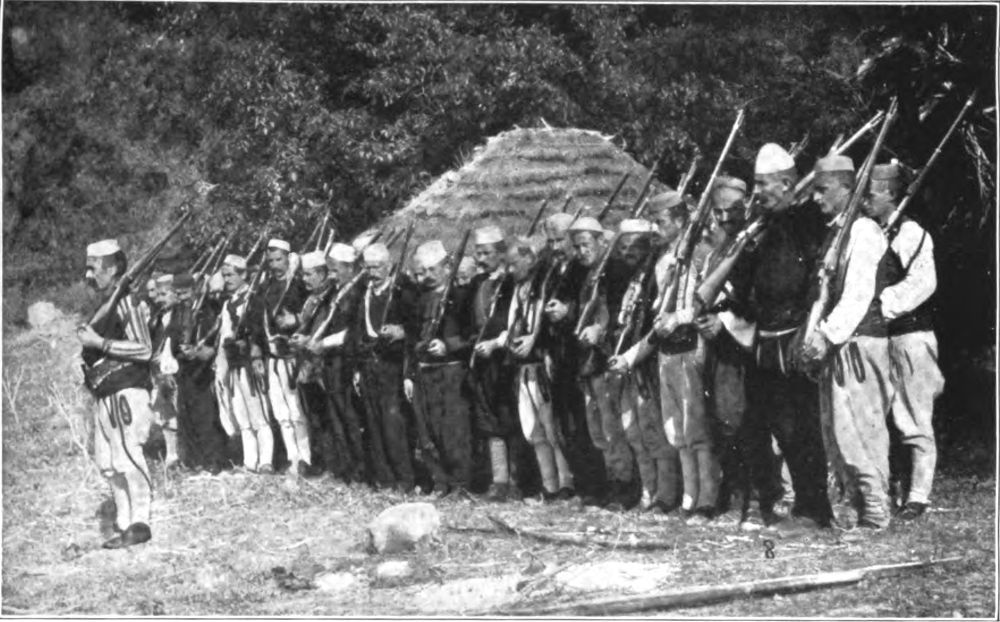

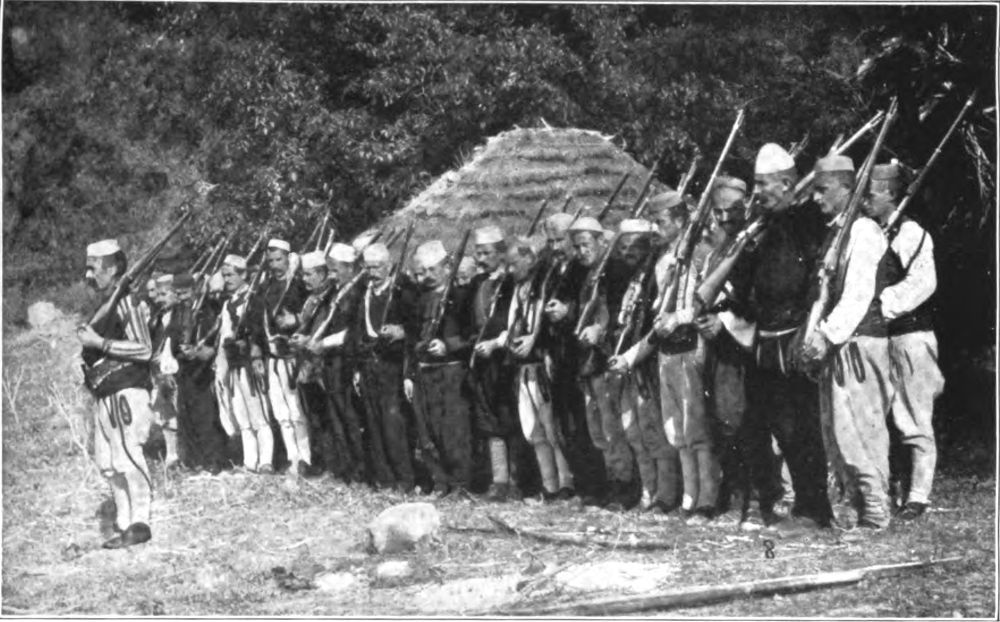

THE FIGHTING MEN FROM THE MOUNTAINS WHO CAME INTO TIRANA TO DEFEND THE GOVERNMENT WHILE ELEZ JUSUF WAS IN TIRANA

In this group are men from seven tribes, distinguishable by the pattern of their trousers.

Nearly noon, and talk stopping in the cafés. Shops closing, quietly, one by one. A tightening, an apprehension, in the air. New faces, new costumes, in the streets. Slowly, slowly, little by little, Tirana was filling with tall, keen-eyed, weather-bitten men. Men in the tight white trousers and rawhide opangi of the northern Tirana mountains. Men in the fuller white trousers and embroidered socks of the central mountains. Men in the very full brown trousers and curve-toed moccasins of more southern tribes. Mountain men, all of them. They sat on the low walls around the mosques, talking. They lounged on the curbstones, they sauntered on the streets. More and more of them. Impossible to estimate how many. A thin little trickle going steadily in and out of Government House. And it was strange how a sense of Government House, a sense of the one man alone behind those broken walls, grew upon Tirana. It was as though Government House were a huge, mysterious, living thing. Men walking in the streets glanced at it furtively, as if it might be watching them. Groups stood and stared at it. There it was, quite still. Still, like a crouching animal. What would it do?

Three o’clock, and suddenly the answer. A gust of rifle shots, a growl of machine guns, and the storm was on us. The streets were swept clean of people in one quick scurry; windows barred, doors bolted. And we were running through a swarm of bullets that sang like mosquitoes. Running, we cried to each other, “Tricked the British Empire, by Jove!” For the very sound of the guns said that this was grim earnest, this was the end. Ahmet had gained time enough to bring in the mountain men. Now he was fighting.

At seven o’clock the next morning he was still fighting. Fifteen hours, without a break, and Elez Jusuf was still alive and still in Tirana. When the firing died in the bright morning we went picking our way through wreckage of mud-brick walls, around bloody cobbles, past plaster houses ripped to tatters by bullets. In the heart of the wreckage Elez Jusuf was still holding out.

At ten o’clock a drum beat in the street before the mosque where the dead men lay, and a crowd listened to the singsong of the government crier of news. He cried that at twelve o’clock Ahmet Bey would burn the quarter that sheltered Elez Jusuf. Citizens whose homes were there had two hours to take out their movable property. Passports to enter and leave the quarter, obtainable at the post office. Machine guns surround the quarter. Listen well! At twelve o’clock the machine guns will start and the quarter will burn. After twelve o’clock no man leaves it alive. By order of Ahmet Bey Mati.

It is impossible to describe the feeling that day in Tirana. It was as though a giant hand closed upon the heart, slowly, inexorably. Death. At twelve o’clock the machine guns will start and the quarter will burn. No man will leave it alive. Five hundred men. And this was true. It was not a dream nor a tale in a book. It was reality. We asked, “Will Ahmet do it?” as one struggles to awaken from nightmare. We were always answered, quietly, “Yes.” Men were not speaking much, that day; they simply said, “Yes.”

The procession began. Women bowed under loads of things, blankets, rugs, chairs, a frying pan, a child’s toy. Children going before them lugging the spinning-wheel, the hand loom. Smaller children stumbling and holding on to skirts. Veiled women, sobbing behind the veils, walking pigeon toed and pitifully on high heels, in hampering trousers, carrying boxes too heavy, so that they must stop to rest. One little donkey, going back and forth, back and forth, bringing out trunks and bedsteads and house doors. And for some time a frantic woman, veiled, hysterical, clung to us, clung to our skirts on hands and knees, talking a language we could not understand, pleading, begging as if for her life, holding up five fingers, measuring five distances from the ground. Maddening, our inability to understand her. Why the five fingers? Five what? How could we do what she wanted? A stranger who spoke French at last translated her words for us. She was a Turkish woman, her husband was in Constantinople; her five children—little, little children—were in the quarter. She had been visiting a friend when Elez Jusuf came in. For two days she had not been able to get back to the children, and now she saw that other people were bringing out things, and the soldiers would not let her in to get her children. We took her to the post office and got her the permit to pass the soldiers. That was that.

At eleven o’clock we met a teacher in the Vocational School. He said: “I have come out for a minute, between classes. It—— I wanted to get away from the boys. We have three grandsons of Elez Jusuf, you know.” We had not known, and, knowing, what could one say? The teacher seemed to feel that speaking about it would make it easier to go back to them. “We couldn’t keep the news out. All these boys know Albanian politics so well. Damn it! the finest boys God ever made.” There were tears in his eyes and his words were not profane. “Not one of them missed one recitation since this thing started. We moved the desks and barricaded the windows; classes going right on. Boys said to me this morning, they can’t fight for Albania, but they can study for her. Breaks you all up, somehow,” he said, apologetically, and blew his nose. “Damn it!” he said again. “I—— That young boy from the Dibra got up to answer a question just now, and forgot the question. I said, ‘Never mind.’ I was going to pass it over. He said: ‘No, please ask it again, sir. I won’t be much longer in class.’ I thought he was going to break down, on that, but he answered the question. Answered it right. Goes straight on, with his head up. Their father’s in that hell hole, too. The boy’ll have to go back and be chief of the Dibra.”

It was impossible to say anything. We shook his hand and he went back to the class. Mr. Eyres and his secretary went back and forth, from Elez to Ahmet, from Ahmet to Elez, hastening, followed by the eyes of us all. Their faces were not encouraging.

Ten minutes to twelve. The last machine gun chuckling over the cobbles. Six minutes to twelve. Files of men, with oil cans, going through the streets. Four minutes to twelve, and the streets emptied save for the last frantic stragglers coming with last armfuls of things. Three minutes to twelve—and the drum beating! The open space before the mosque was a mass of bodies, a suffocation of held breaths. Listen well, people of Tirana! Elez Jusuf asks for time. A council is talking. At two o’clock the machine guns will start, and the quarter will burn. At two o’clock. By order of Ahmet Bey Mati.

It would seem that the pressure of that giant hand would ease, but it continued to tighten slowly, minute by minute. It continued to tighten, even when at four minutes to two o’clock the crier called that the council was still talking. Four o’clock, the third, last order. At six minutes to four o’clock men were going with lighted torches; the oil had been spread and wooden sprayers had thrown it over the roofs. At five minutes to four o’clock the roar of an automobile in the streets, and Elez Jusuf appeared, riding to Government House in the English car, Mr. Eyres beside him. Tirana followed them to the gate in a wave of men, a wave that slowed, eddied before the gate, and stopped. It seemed that time stopped with it.

Out of the gate a rider, lashing a galloping horse. Clatter of spark-scattering hoofs on the cobbles, swish of the whip, and a swirl of wind following. Four o’clock, and the ripping sound of one machine gun, stopped abruptly. No more.

Ten minutes after four o’clock, and Elez Jusuf and Mr. Eyres riding out of the gate. Elez Jusuf sat straight and proudly; a fine old mountaineer in his Scanderbeg jacket and silver chains, overlooking the crowd as though it were not there. Only a glimpse of black Scanderbeg jacket, silver chains, gray hair, profile of firm lines, and Elez Jusuf had made entrance and exit.

Immediately after the automobile, while the gate of Government House still fascinated, two riders came through it. They were Austrian engineers, in khaki riding clothes and puttees. They rode pack mules, and camping outfit complete with tent was roped to the wooden saddles. We knew them slightly, and stopped them as they came leisurely by, to ask what they knew.

Nothing, they said. Ahmet had sent for them that morning—they were engineers employed by the government—and had asked them to make ready to go out toward Dibra, to investigate and report on the possibility of lighting Tirana with electricity from a waterfall twenty miles away. They had been ready at one o’clock, and Ahmet had sent asking them to wait, ready, in the courtyard of Government House until he gave them the word to start. Word had that moment come, and they were starting.

They stirred the smallest of interest as they rode on through Tirana. Tirana was relaxing, as a tired man sighs. Men sat on the curbs, on the low walls, on the ground. There was a crowd in the cafés, but no singing, and little talking. The sunset hour was beginning, but no one walked.

In the whitewashed dining room of the Vocational School we sat drinking tea. Mr. Eyres disclaimed the tiredness of his eyes. It had been most interesting, he said. An interview he would not forget, that between old Elez and Ahmet. “A strong man, Ahmet. Perhaps a little young, just twenty-six, they tell me. Well, time will remedy that.” Elez had been persuaded to go to Government House to meet and talk with Ahmet. “Really a remarkable man, old Elez. He’d never before seen an automobile, you know. Walked right up to it, sat in it, as though he had ridden in one all his life; never turned a hair, coming or going. Must have been a bit of a strain, after all he’d gone through.” He said to Ahmet that he had talked with his men. They would not give up their rifles. If it were required that they give up their rifles, Elez would go back to his men and they would die fighting. Ahmet said, “Mustapha Kruja will be hanged when we find him. Zija Dibra must leave Albania forever. Give me a besa of peace and go back to the Dibra with your rifles.”

Elez was silent a moment, and then gave the besa. The Dibra, he said, would be loyal to the Constitutional Government of Albania as long as he lived, and as long as his son’s sons ruled the Dibra. He saluted, Ahmet saluted; the official interview was ended. And the messenger left to countermand the orders given. “Something rather dramatic about these chaps, really. Done just like that. No palavering, no signing of papers. Not necessary, and Ahmet knows it. Elez would be cut into bits before he’d break a besa. They’re admirable, in their way, these men.”

Elez, turning to go, had turned back to speak again to Ahmet. The Dibra and the Mati had long been enemies, he said. There had been no friendship between them since the days of Scanderbeg. Was this not a time to forget that old enmity? In their mountains, Dibra had not understood the Tirana government. During those three days in Tirana, Elez said, he had learned many new things. He believed now that Ahmet Mati was fighting for Albania. Would Ahmet join him in a besa of peace between Mati and Dibra?

This had been entirely unexpected, Mr. Eyres said. However, Ahmet did not turn a hair. He and Elez made the besa of peace, and then Elez added another thing. “I have heard,” he said to Ahmet, “that you intend to disarm the men of Dibra. You have not expected to do that without fighting. Now I, Elez Jusuf, chief of the Dibra, say this: The Serbs hold our city of Dibra. The Serbs are on the lands of my people. Twice in this year the Serbs have come to kill our men and burn our villages. Only our rifles stand between us and the Serbs. But you are the chief of Albania and you are a wise chief. When you think it is time to come to the Dibra to take away the rifles of the Dibra, I will give you every rifle. There will be no trouble. I say this, on the honor of Dibra.”

Even this, to Mr. Eyres’s deeper astonishment, did not cause Ahmet to turn that hair. He said merely, “That is well.” The interview was ended. On the way back to his men, Elez suggested to Mr. Eyres that he leave his son as hostage to insure that he had spoken the truth. If he broke the besa, he said, in a matter-of-fact manner, Mr. Eyres might kill his son. Misunderstanding Mr. Eyres’s reaction to this offer, he added that his son would be glad to make his life a forfeit for the honor of Dibra. “But what on earth would I do with the chap?” said Mr. Eyres to us. “Bless my soul, I know old Elez will keep his word! Well, rather! I told the old man to jolly well take his son along with him. By the way, the young Elez has two lads of his own here in this school. Asked me to give them greeting from him, said he was sorry he couldn’t stop to see them. Elez’s riding out on the Dibra trail by this time, I expect.”

The young secretary of the absent Prime Minister came at that moment to confirm this conjecture. The crisis was over. Albania, we said, was saved once more. If the uprising had been—who could say?—an Italian plot, Italy was checkmated again. There would be no new outbreak in the Balkans this time, and that precarious balance in all European politics, the Balkan equilibrium, was unchanged. We were saying this, and I was thinking of the two Austrian engineers riding behind the retreating Dibra men on their quest for electric lights for Tirana, when the second blow fell upon us.

The Red Cross mail car, gone that morning to meet the Italian steamer at Durazzo, returned with the news that Hamid Bey Toptani, brother of Essad Pasha, had taken Durazzo. He was an hour from Tirana, coming on the Durazzo road, with at least six hundred armed men. How many more were hidden in the hills when the automobile passed, no one could guess. Under the American flag, the car had gone and come through the lines, and no secret had been made of the fact that Tirana would be attacked that night.

There is a point at which human nerves cease to report emotion. For three days and nights we had felt all that we are capable of feeling. We heard this news blankly, understanding it, thinking about it, and hardly caring. There was no resilience left in us with which to care. It was like beginning again a story we had once read.

“Where did Hamid Bey Toptani get his arms?” I asked. For the Toptani family are not mountaineers, nor chiefs of mountaineers. The peasants on the great estates of the plains do not carry rifles.

“There is an Italian gunboat in the harbor of Durazzo, and another at San Giovanni,” said the American who had gone with the mail.

“It does look like a well-organized plan,” we said. Scutari attacked, Elbassan attacked, Durazzo taken, Tirana attacked from the west and from the east. A plot, in which only one small thing had gone wrong. Had old Elez Jusuf, tricked by his two friends into involving the Dibra, come too early to Tirana? Had Mustapha Kruja and Zija Dibra intended to bring the Dibra men from the east when Hamid Bey Toptani came from the west? Was it because the plan miscarried that they had urged Elez Jusuf to sit intrenched in Tirana, while they hoped that Toptani would come in time to help them take Government House? Or had the Dibra men come on time, and Toptani purposely delayed, to leave the hard fighting in Tirana to the Dibra men?

Futile questions, for we could not know the answers. And our thoughts settled upon Ahmet, three days and nights without sleep or rest, the one man who was the government, sitting alone in Government House with the checkerboard of this situation before him. How well he had moved the pieces! Bringing in the British minister, to give him time to bring in his fighting men. Settled, in his mind, that to-day must remove Elez Jusuf, though he burned half Tirana to do it. And sending out, ten minutes behind Elez, those two engineers to plan electric lights for the capital! To plan electric lights for the city that—surely he knew it—Hamid Bey Toptani would attack that night. Ahmet, the Hawk, chief of the Mati, come from the court of Abdul Hamid when sixteen years old, to fight the Serbs in the mountains. The chiefs of the Mati must lace his opangi before every battle, because he did not know how to lace opangi. But the chiefs of the Mati loved him.

Two horses went cantering past the windows of the Red Cross dining room, and because the clatter of horse’s hoofs is rare in Tirana they must be bringing news. From the gateway of the courtyard we watched them—a rider in the Mati costume, leading a lean, eager bay horse. They went through the gate to Government House. In a moment they reappeared, Ahmet Bey Mati riding the bay. He still wore the clothes in which I had seen him; rumpled a little, they spoke of the sleepless nights, and his face was white with fatigue. On his head an astrakan fez; over his shoulder the strap that held a rifle; around his waist the cartridge belt, and a belt holding silver-hilted revolver and knives. A strange figure, in tailored business suit, riding the lean bay through the streets of Tirana. Behind him, coming with the long swinging walk of the mountaineers, perhaps sixty Mati men.

“Long may you live, zonya!” said he, touching the astrakan fez in salute.

“Long may you live, Ahmet Mati!”

They rode past the pictured mosque, down the street of little shops and cafés, closed now, past the cemetery with its toppling turbaned gravestones. At the barracks they stopped. For a moment Ahmet spoke with the chiefs who gathered around his horse. Then he rode on, out on the road to Durazzo, and behind him went his hundreds upon hundreds of fighting men. It was the sunset hour; the mountains and the sky were beautiful, and the little owl was beginning to call from the Cypress of the Dead. The prayers of the hodjis rose to Allah from the tops of the white minarets.

The moon was late that night, and mountains and plains were covered with darkness when the rifles began to crackle on the hills. Little flames of rifle fire ran along the tops of the hills like flickering lightning. It was as though the hills were crackling with electricity.

We stood in the courtyard of our house, watching them. Government House was dark; the engine was no longer running. The little owl called from the Cypress of the Dead. Sied Bey came through the gate and said to us in French that he feared there would be trouble again in Tirana that night; might the women and children of his family stay in the Red Cross house? There was his old mother, who was ill; his sister, and many children of his brothers and his cousins, little children. They had come in that day from his estate, where the fighting was. Did we think the Red Cross would give them shelter till morning, under the American flag?

They came behind him, through the darkness, and we said we would take them to the Vocational School. Sied Bey could not leave his post at Government House. There were the two veiled women, and nine women servants carrying rolls of bedding, and so many little girls in voluminous trousers, with chains of gold coins on foreheads and necks, and so many very small boys in Turkish trousers and Scanderbeg jackets, that we never counted them. We got them all into the Red Cross dining room, where there was space for them to sleep on the floor, and we offered them cigarettes and coffee. Within the dining room the sound of the rifle fire was no louder than the soft crackling of burning wood.