CHAPTER XIV

A NIGHT BY THE BYRAKTOR’S FIRE—THE BYRAKTOR CALLS A COUNCIL—REXH TO THE RESCUE—THE BYRAKTOR’S GENDARME TEARS A PONCHO—MOONLIGHT ON THE SCUTARI PLAIN.

Then his grandmother made three beds, on three sides of the fire. She brought a two-inch-thick mat of woven straw and laid it on the floor; over it she spread a handsome blanket of goats’ hair dyed in stripes of magenta and purple; under one end of the mat she put a triangular piece of wood to serve as pillow, and when I lay down she tucked other blankets over me. Rexh and the Shala man had the other mats, and all the byraktor’s family went to their own places, leaving the big room and the dying fire to us three guests.

At four in the morning the house was astir. Out of the darkness yawning men came to stir the slumbering fire; the byraktor appeared without his turban, a weird figure with his shaven, skin-white head and long black scalplock, and began to make the morning coffee; the sheep and goats were driven out into the rain by the ragged shepherdesses. I sat up and put on my opangi, and the sleepy Rexh, still streaked with red dye from his fez, rolled out of his blankets.

“To-day,” I said, “we get to Scutari.” For the pains in my lungs had returned and I had lain all night half waking, haunted by fever visions and voices.

“Yes, yes,” said the Shala man. “I swear it! To-day we get to Scutari!” But the byraktor looked at him, saying nothing, a quizzical look in his dark eyes, and leisurely went on with his coffee making.

“Rexh,” I said at five o’clock, “why don’t they start?”

“I don’t know, Mrs. Lane,” he replied, earnestly. “They will not tell.” He sat listening to every casual word, and thinking deeply. A dozen times I had suggested that we should be starting.

“Tell the byraktor we must go!” I said at six o’clock, impatient in the doorway. For a long time all the world had been a clear gray, shadowed only by the falling rain. “I pay a hundred kronen for his mule only because it gets me to Scutari to-night.”

Rexh announced this firmly to the byraktor; the byraktor, listening attentively, assented with a shake of his head.

At seven o’clock I walked madly up and down the small stone porch. The byraktor’s gendarme had arrived; he stood washing his face in a stone basin filled with rain water; at every splash in it he raised his head and solemnly crossed himself and made the sign of the cross toward the dawn. Inside the house, the byraktor was deep in conversation with his grandmother.

“They are talking politics, Mrs. Lane,” Rexh reported. “I do not yet quite understand, but I think that you will not get to Scutari to-day.”

“Rexh,” I said, “listen to me. I shall get to Scutari to-day. In ten minutes by my watch I shall start to walk to Scutari, without the mule. I have waited long enough. Tell that to the byraktor.”

The byraktor came to the door and looked at me kindly. He had put on his turban; he was a figure of rather awe-inspiring dignity. “Slowly slowly, little by little,” said he, indulgently, and went back into the house.

When eight minutes had passed his grandmother came out—I was now walking restlessly up and down the soaked, corn-stalk-strewn yard—and led out of the lower part of the house the mule. The mule was the very smallest donkey I have ever seen, the most bedraggled, the most violently antagonistic to all the world. The woman tied him to the wicker fence and brought out a measure of corn. “Slowly, slowly,” said she to me, triumphantly. “One cannot start until the mule has eaten.” Then she went back to her talk with her grandson, the byraktor.

A moment later I interrupted them by the most courteous of farewells. I blessed them and their house and their past and their future, their families, their tribe, their hospitality, and their mule, and then I left. The Shala man followed me, protesting; Rexh trudged beside me, saying nothing, but very disapproving.

“You cannot do such a thing to the byraktor of Shoshi!” said the Shala man.

“I have done it to the byraktor of Shoshi,” said I, violently, gasping on the trail. I kept my knees stiff with sheer rage, but on the first terrace above the byraktor’s house not even that could keep me going, and I sat down in a heap on the trail to rest.

The sun had not yet cleared the top of the stupendous sweep of striped rock that soared above the chasm; it could hardly do so before noon. The cañon was filled with silver light; the rain itself seemed silver; the rose and blue and white of that great cliff glowed softly through it, and the greens of the little fields below were soft as mist. I sat looking at this, and insensibly realizing why time was so little to these people, and how unimportant, really, all our little hastes are.

Then, coming leisurely across the green, like little toys on a carpet, appeared the byraktor, his gendarme, and the minute mule. In half an hour they reached us, calm and unperturbed. The donkey bore a wooden saddle quite as large as himself; they placed me on this and leisurely began to climb.

“To-night,” said I, firmly, “I shall be in Scutari.”

Rexh translated this to the byraktor, but the byraktor said nothing.

We proceeded slowly over the mountains. This was wilder going than I had yet seen, and again the simplicity of these people was borne in upon me. Coming to places that, to any European understanding, would be absolutely impassable, the byraktor’s action was simple and direct. He wrapped around his wrist the steel chain that held the mule by the neck, and easily, without haste, he went on. The mule came, too; it could not do otherwise, and when it would have fallen the steel chain and the gendarme’s firm grip on its tail kept it going until its feet got their grip again. I was, of course, on the mule’s back, and where it went I went, too.

The byraktor and the gendarme thought nothing of thus casually carrying between them a mule with me on its back, and very shortly—so adaptable is the human mind—I thought little of it myself. I recall sitting there, comfortable in that armchair of a saddle, taking my smoked glasses out of my pocket and polishing them; the sun was piercing through the clouds, and the glare on the snow above was blinding to my eyes. We were passing along a trail really too narrow for the mule; my knees grazed a cliff; a glance over my shoulder went straight down into depths where pine-tree tops looked like a lawn; at every second the mule’s tiny hoofs slipped and rocks showered downward, the chain tightened around the byraktor’s wrist and the muscles of his shoulders knotted as the mule’s weight bore on them. It crossed my mind, as I settled the smoked glasses on my nose, that two weeks earlier my heart would have stopped at very sight of that trail, and then, as it dipped downward and I heard the gendarme bracing his feet and felt the mule’s weight sag against the strength of that useful tail, I looked up and forgot everything else in the magnificence of shadow and sunshine on the snow-piled heights.

I do not mean that I am at all unusual in my attitude to danger. I’m not, and the prospect of sudden death scares me stiff, as it does everyone else. I mean that human beings are all chameleons. The stuff of humanity is always the same, it merely takes on different colors from its environment; in Albania there is not one of us who will not become Albanian. There are many morals to be drawn from this; you may apply the idea to education, or to your attitude toward immigrants or capitalists or criminals or even to your next-door neighbor; it would be useful also in considering international politics or religions that are not yours, or the actions of men in war, but I did not draw any morals, being immediately engaged in crossing the foot of the largest waterfall I had yet encountered.

It was so large that the men unsaddled the mule, stripped themselves, and wrapped their clothes in several bundles before attempting to cross it. Then they made a living chain of themselves; the byraktor, at its head, advanced to a water-worn bowlder in the center of the current, braced himself firmly, and became the pivot on which the chain moved. The end man carried over the clothes, bundle by bundle, wrapped in my poncho; then he carried me across—I was soaked in spray, but that did not matter. Then he put one arm around the donkey and supported it across, and then the saddle, and then he went back once more and took the protesting Rexh and brought him over. The water was above their waists; their white bodies slanted in the glassy current; three yards below them the water poured in a crystal mass over the edge of the pool, a second waterfall that struck in roaring foam fifty feet below.

The worst of the current was between me and the central rock where the byraktor was braced; several times the end man’s feet slipped there, notably when he crossed with the donkey, which I gave up for lost, but each time the chain of hands held firm.

Their bodies came blue from the icy water, but they put on only their cotton underdrawers, for they said we would next go through the snow, and they did not want to get their beautifully embroidered trousers wet; for the same reason they left their purple, gold-embroidered socks and rawhide opangi in the packs, and went on barefoot.

“Good! If we’re crossing the snow fields already, we’ll surely be in Scutari by to-night,” I said. But I was joyful too soon, for when we reached the first of the snow the party stopped. The byraktor sat down on a rock and lighted a cigarette; the gendarme, without a word, began to climb a tall cliff that overhung the trail. What did it mean? Rexh did not know, and I sat impatiently on the mule, which began nosing through the snow for some bite to eat.

Then overhead the high, keen telephone call rang out, answered by far, thin voices that sounded as though the crystal air itself had been tapped, far away, by a giant finger. Even while the voices called and answered in the sky, silent men began to appear, suddenly, without my having noticed their approach. It was startling to see a strange, turbaned head beside my elbow, to find that between two glances a dignified, half-naked man was sitting on the rock beside the byraktor.

Rexh came and led the mule to a little distance. The figure of the gendarme, against the sky, raised its rifle, and I put my hands over my ears just in time to dull the echo crash. “It is polite to go away for a little distance, Mrs. Lane,” said Rexh. “The byraktor has called a council of all chiefs of Shoshi.”

In half an hour twenty men surrounded the byraktor. They were all, like the byraktor and his gendarme, in cotton underdrawers, barefooted, and naked above the waist, many of them wearing on their heads only the tiny round white cap that covered their scalplocks. Each of them carried his rifle on a woven strap slung over his shoulder, and all had an arsenal in their sashes. They sat on small rocks, on the snow-filmed ground, in a group about the byraktor’s bowlder.

We were at the mouth of the highest pass. All around the little open space towered cliffs heavy with snow, only to the east the mountain ranges fell away, one beyond the other, to the just-suggested chasm of the Lumi Shala Valley, and beyond it they rose again, purple and blue and gray, to the foot of the great wave of snow that touched the sky—the wave that Alex and Frances and Perolli were climbing, if they had left Shala. A black cloud hanging over the pass they were to take told that they were traveling in a storm.

The council lasted half an hour, three quarters of an hour, an hour. It concerned grave matters; the earnestness of those intent bodies and keen faces said that. Meantime Rexh and I talked in low tones.

“I am not paying the byraktor a hundred kronen to sit here while he holds a council,” said I. “Do you think he intends to get me to Scutari to-night?”

“I do not think so, Mrs. Lane. But if you want to get there, it shall be done. We must consider many things.” Rexh used his fingers to check them off. “First, the byraktor must be thinking a great deal about the new Tirana government. You remember that he asked the Shala man about Rrok Perolli. Also he talked a long time with his mother’s mother, and that was about politics. Second, the byraktor holds a council. Therefore he is going to do something that concerns the tribe. The byraktor, you know, is the war chief; he is the one who leads the tribe to war. Shoshi is in blood with Shala, and Shala has sworn a besa with the Tirana government. We must think of all these things. Now I think that the byraktor is also in blood with some of the tribes along the Kiri River, between here and Scutari. I think that he has hired you the mule so that he can travel in safety with you through those tribes and get to Scutari, where he will inquire about the Tirana government and whether it intends to join Shala in war against Shoshi. That is what I think.”

I looked at that twelve-year-old lad in amazement and admiration. “Well, Rexh,” I said, humbly, “I must leave it to you to get me to Scutari to-night, somehow. You think the byraktor intends to stop along the way?”

“Yes, Mrs. Lane. Also I think that the Shala man does not want to reach Scutari to-night. He swears earnestly, but I think he is a serpent with a forked tongue.”

I sat there on the donkey, appalled. “But, Rexh, you know that I must get to Scutari to-night. Tell them I have said it. I am of the American tribe, and what Americans say they will do, they do. To-night I get to Scutari!”

“Yes, Mrs. Lane. But one must not tell all one thinks. We will say nothing. We will see.”

When the council was ended we went on leisurely through the pass, and down into valleys, and up again over other mountains. At two o’clock we left behind the last glimpse of the wall of snow to the east, the last sight of the interior mountains of northern Albania, the most beautiful mountain country in the world. At three o’clock we saw, glimmering on the far-western horizon, the silvery edge of Lake Scutari, and far to the right, deep between two ranges, the valley of the tribe of Pultit, and the white house of the bishop, the tiniest of specks to my eyes; but the Albanians saw it plainly, and distinguished it from any other.

At four o’clock we began the tremendous descent into the Kiri Valley and I was obliged to dismount. “The gendarme says he cannot hold the donkey by the tail here, Mrs. Lane. He is afraid the tail will break.”

And for two miles we swung downward bowlder by bowlder, exhausting travel to the arms and shoulders; but the mountain women came up that way with cradles on their backs. The mule made it by little leaps.

“Now the road is good,” said the Shala man, and, indeed, the two-foot path, no steeper anywhere than the steep trails on Tamalpais, seemed a boulevard to me. Only twenty miles more to Scutari! And I thought of getting off the clothes in which I had slept for three nights, and a shampoo shone before me like a bright star. Rexh had been borrowing trouble, I thought; there was still light on the western slopes and twenty miles was nothing to these people. And just as I was thinking this the byraktor halted.

“We will go this way, now,” he said, “to the village where we stay to-night.”

Why was it so necessary that I reach Scutari before I slept? I do not know. But the idea had become fixed, an obsession; I was irrational, for the moment a monomaniac. There was nothing I would not have sacrificed to satisfy that imperious desire.

“Tell the byraktor that I must get on to Scutari,” I said. “I am sick and must get quickly to a doctor. I cannot stay in any village to-night; I must be with my own people.”

“Yes, Mrs. Lane,” said Rexh, and, having talked for some time, he explained, “I have told him that you have had word from your father, who is the chief of your tribe, and that the word said you must go to Durazzo and take a boat to your own country.”

“Very well. What does he say?”

“He says that you stop in this village to-night. It is a good village, and you will be rested in the morning.”

“I will be in Scutari in the morning,” I said. “Tell him again that I must go to Scutari. If he cannot go himself, will he let me take the mule?”

“But he says the roads are dangerous and it will be dark.”

“Tell him I am American and there is no danger that stops an American.”

The byraktor looked at me, puzzled, but with a little humor in the depths of his dark eyes. He had put on his turban; below its white folds the silver chain dangled on his bare breast; above it the muzzle of his rifle caught a glint of the western sunlight.

“He says it is not a question of your safety; it is a question of his honor. I was right, Mrs. Lane; he says that he is in blood with the tribes through which one goes to Scutari. If he travels through them by night he will be killed, and in the darkness no one will know who has done it. He does not mind being killed, but to be killed by some one his tribe cannot know and kill afterward would be black dishonor to him. It is true, Mrs. Lane, and he is a great byraktor—the byraktor of five hundred houses.”

“But he need not go with me. You and the Shala man will go with me. I only want his mule. Is he afraid for his mule? I will give him a paper, and if I am killed and the mule is stolen he can get another mule from the Red Cross house in Scutari.”

I said this quite innocently, but the words taught me what blazing eyes are. One hears of them; one seldom sees them. But the byraktor’s eyes seemed actually to kindle into flame, and involuntarily I shrank back when he turned them on me.

“He does not think of the mule, Mrs. Lane. He thinks only of his honor. You must not say such things. He says you cannot go on without him; you are traveling under his protection, and it is his honor that is concerned if anything happens to you.”

I looked at the ring of utterly savage-looking men, half naked, with shaven heads and scalplocks, surrounding me in those wild mountains, and suddenly I struggled not to laugh. If a magic vision could have shown me then to my friends at home, how they would have prayed that I escape alive, while the real difficulty was that these savages wanted only too embarrassingly to protect me.

“But, Rexh, it is absurd. I did not ask for his protection; I simply hired his mule. Tell him that he has brought me so far safely, so far I have traveled under his protection. I thank him, I thank him deeply, I am most grateful with my whole heart, but now I will leave his protection and travel onward.” And to Rexh’s words, with my hand on my heart, I added in Albanian, “I thank you from my heart.”

The byraktor made a gesture, only a little gesture with his hand, but the violence of its fury I cannot describe. “You thank me! You have broken my honor!” he said, and even without Rexh’s murmured translation I would have felt the menace of the silence that followed.

“But,” I said, bewildered, “I am traveling with the Shala man. Isn’t the Shala man protection? Besides, tell him I don’t need protection. I am protected even here by the power of my own tribe.”

“The Shala man shall take you in, Mrs. Lane,” said Rexh. That too-handsome youth had hung back from the conversation, but Rexh’s stern eye brought him into it. And then there was such a battle of words that the very rocks joined it. The byraktor stood listening, bending down a little, intent; Rexh—short, pudgy Rexh in his flannelette pajamas—drove home with fist on chubby fist his earnest words, and the Shala man called Heaven and the cliffs to witness his clamor. The byraktor turned his eyes from Rexh to the Shala man, from the Shala man to Rexh, and thoughtfully stroked his chin. Around us the other men stood attentive.

Then the Shala man turned and, lifting me from the trail to which I had dismounted, swung me again into the saddle. He pounded the saddle with his fist and exclaimed violently, his face congested with dark blood.

“It is all right, Mrs. Lane,” said Rexh, grimly. “He will take you in. He has told the byraktor why he cannot take you to Scutari; it is because the gendarmes are looking for him to kill him. But he will take you in. After that the gendarmes can have him; he is of no use.”

Even my fixed idea was shaken by those astounding, calm words.

“But, Rexh,” I said, in horror, “I can’t kill a man, even to get to Scutari to-night. Do you think the gendarmes will really kill him if he takes me in?” But one glance at the violently miserable Shala man answered the question.

“Yes, Mrs. Lane,” said Rexh. “They will kill him by law, because he has killed some men. But, Mrs. Lane, he said he would take you to Scutari and he must take you to Scutari. The byraktor will tell you so.”

“Po, po,” said the byraktor, agreeing, and, “Po, po,” said the others; and looking at the Shala man, I had no doubt that if he faltered on the way Rexh’s tongue had barbs to drive him onward.

“But explain to the byraktor that it is not American custom—that I can’t take a man to be killed, Rexh. I’m sorry,” said I, for it did seem a pity to disappoint Rexh so, when he had so nicely arranged everything. I leaned from the saddle and spoke earnestly to the byraktor myself, Rexh’s murmured translation for his ears while I held his eyes: “I must get to Scutari to-night. It is necessary. But I do not want to risk any man’s life. I take my own life in my hands and go with it on the trail. No one else can carry it for me. That is American custom. It is American custom that I thank you now, and give back to you your protection, and go on alone. If it is not your custom, I am sorry, but by all American custom your honor is safe, and I am American, and Albanian law does not apply to me.”

“You speak with a tongue of great learning,” said the byraktor, but this time his manner was sympathetic. “However, my honor is my honor, and my protection goes with you all the way to your own tribe. I will go with you to Scutari.”

“But I don’t want the byraktor to be killed, either!” I wailed; and then the byraktor’s gendarme came forward. He was a low-browed, rascally-looking fellow, a man with bad eyes like those of an untrustworthy horse, and a charming smile. He was naked except for the wide scarlet sash around his loins and the tiny white cap over his scalplock.

“The honor of my byraktor is my honor,” he said. “My byraktor is a good byraktor and a great byraktor. He is byraktor of five hundred houses. If he is killed, all the valley mourns. If he is killed in the dark and we never know who killed him so that we can kill that man, that is black dishonor for all the tribe of Shoshi. I am only one man, and if I am killed it does not matter. I will go with you to Scutari.”

“Glory to your lips!” said the others. “Good! It is decided.”

“Well,” I thought, “all this is beautiful rhetoric, but no one will kill him while I am with him.” As for the danger in the darkness, I did not believe it for a moment. Who would shoot a person he could not see? So I said good-by to the byraktor—all our long and flowery speeches consumed another quarter of an hour, and the sunlight was climbing away over the mountains so rapidly that we could see it go—and I said good-by to all the others, and promised the frantic Shala man that indeed he should be paid what had been promised; I would send him the money by the gendarme, and I would send the mule and the hundred kronen to the byraktor—and then another difficulty arose. If I left the Shala man unprotected here, in the midst of the Shoshi men who had traveled amiably with him all that day—but he had never wandered beyond eyeshot of me—his life would be no safer than in the hands of the gendarmes of Scutari.

I actually felt despair when Rexh pointed this out. “Well, but he has to get back through the tribe of Shoshi somehow, anyway, hasn’t he? Why on earth did he ever start this idiotic trip?”

“He wanted the money, Mrs. Lane, and he cannot think ahead. He came through Shoshi only for a joke. If he can get away alive from these men he can go back through Pultit.”

“Well, ask the byraktor if he will give me this Shala man’s worthless life. Ask him not to let his men shoot him until after to-morrow night. Ask him if the Shala man may stay safely under the byraktor’s protection until the gendarme gets back with his money, and then go in peace.”

So this was arranged, and the Shala man, turning his beautiful eyes most languishingly to mine, fervently kissed my hands in Italian fashion; and again I said good-by to the byraktor, and at last, just as the last sunlight left the mountains, Rexh, the gendarme, the mule, and I continued our way toward Scutari.

We followed the winding trail along the banks of the Kiri River. Twilight was over the rushing waters and the cliffs; all along the way the trees were misty green with the youngest of new leaves, and the air was very pure and still. It was all peaceful and very beautiful, and, lulled into dreaminess, I leaned back in the wooden saddle, watching the first stars pricking through the sky. The only sounds were the little tinkling of the donkey’s steel-plated hoofs upon the rocks, and the pouring, rushing noise of the Kiri. Mile after mile we went, the narrow cañon opening fresh vistas before us at every turn of the trail around the cliffs, and the twilight grew grayer, the stars brighter.

But we were coming down the river, out of the mountains, and a sudden shaft of pale sunlight striking a green hill on the other bank surprised me by announcing that the sun had not yet set on the Scutari plain. It was like coming into a new day. I sat up.

“Tired, Rexh?”

“No, Mrs. Lane.”

“But you’ve been walking twelve hours! Sure you don’t want to ride?”

“No, thank you, Mrs. Lane. I am truly not tired.”

“I think I’ll walk awhile,” said I, sliding down from the saddle. Even then he would not ride, but it was good to stretch tired muscles again, and, hand in hand, Rexh and I ran for some time along the almost level, winding trail, splashing through the little streams that crossed it, until suddenly Rexh stopped.

“We must not leave the gendarme behind, Mrs. Lane. Some one will shoot him.”

“So they will!” said I. “Well, let’s wait for him.”

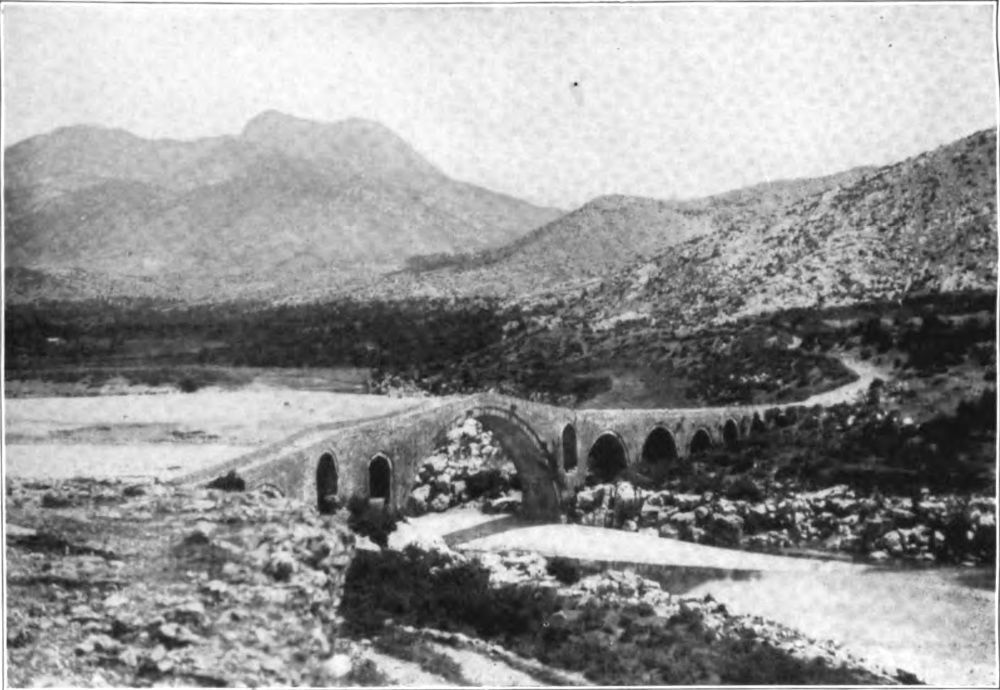

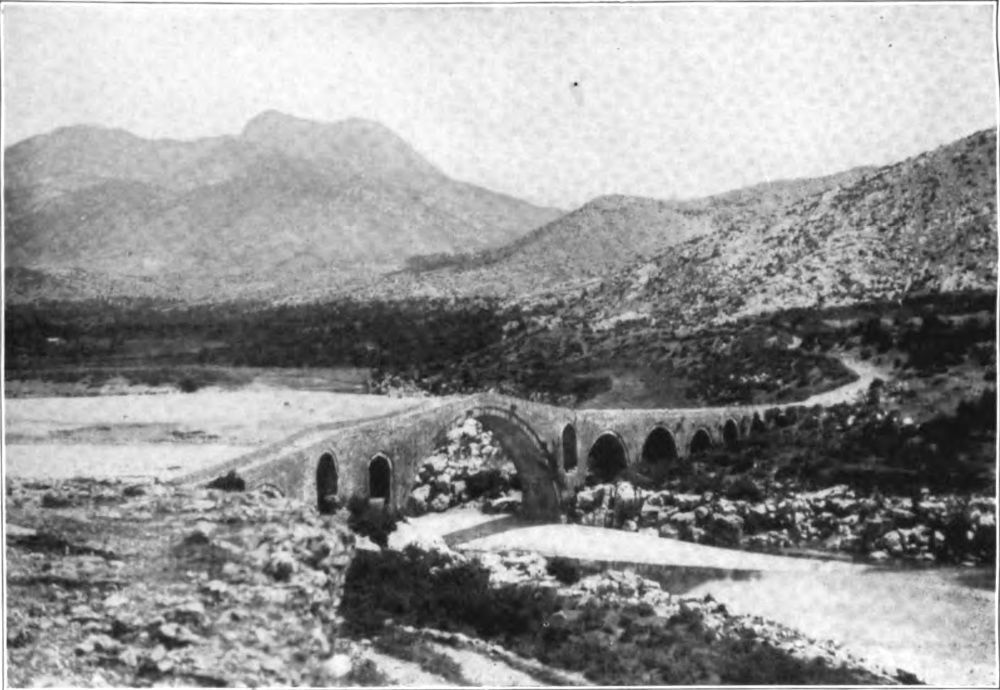

He overtook us, hurrying the mule with blows, and we fell in behind him, speculating now and then around which turn of the cliffs we would first see the Kiri bridge, that lovely succession of old stone arches, built long ago in the Italian style, and wondering what the girls in the Red Cross house would say when we so unexpectedly arrived.

The crash of the thing that happened was like an explosion—over before one had time to comprehend it. I happened to be looking toward the gendarme, a couple of yards ahead of me, walking at the donkey’s head; I had just taken my eyes from the creamy blue river and I saw him reach for his rifle. A misty rain was falling; he had thrown my poncho over his shoulders; the strap that held his rifle ran under it. His gesture was quick and desperate, some part of the rifle caught on a rent in the poncho and the heavy oilcloth ripped apart with a loud tearing sound. The broken, frantic, struggling movement was printed on my eyeballs, and then with headlong leaps I had reached him; we stood beside a bowlder that had blocked my view of the trail, and in front of us were two rifles, pointed straight at us.

There were two men behind the rifles, but I swear that I saw only the rifles. I flung out my hand and heard the most fluting feminine voice I have ever commanded crying, “Long life to you!” And then the rifles fired.

I have tried to give the effect of the thing as it happened; I may now say at once that I was not killed, though I shouldn’t have been at all surprised if I had next realized that I was dead. Instead, I saw two very haughty and displeased Albanians advancing up the trail. “And to you long life!” they said, stiffly, and turned their heads from the gendarme as they passed him. When they were quite gone I was startled to find myself in a heap on the trail, weeping aloud like a six-year-old. It’s odd how such things take you; I suppose it was the surprise of it.

THE KIRI BRIDGE

The gendarme did not seem unduly excited. He said he had killed the cousin of one of those men not long before, and had been a little afraid of meeting him on this road. He said they had lifted their rifles when they saw me, and the bullets had gone over our heads. He said that from now on, if I did not mind, he would wear my hat as a disguise, because there were more of that man’s relatives about. And would I mind walking beside him until we passed the Kiri bridge? He would then be out of the dangerous territory. As for my poncho, he was very sorry that he had torn it. I assured him that it did not matter.

I walked beside him all the way to the Kiri bridge, and then got on the wooden saddle again and leaned back and rested. There was still an hour of traveling across the Scutari plain.

The sunlight faded from the silvering western sky, the western mountains were low dark shapes blotting out the stars. Far away a light twinkled on the citadel of Scutari. For a long time it was the only light in a vast darkness, and then the moon rose slowly above the snow peaks of the eastern mountains. The sky was the pale blue of a turquoise, flooded with creamy light, the lake of Scutari was a silver glimmer, like quicksilver spilled far out on the plain. All around us the tall spikes of yucca blossoms stood vaguely creamy in the moonlight. We traveled over the silent land like silent ghosts, our shadows wavering uncertainly beside us.

The donkey walked with little, quick, indefatigable steps; the gendarme swung along easily, his rifle on his back; Rexh trudged beside me with his hand on the saddle. The soft earth let us pass without a sound.

“Tired, Rexh?”

“No, Mrs. Lane.”

“What is the matter?”

“I am thinking that you will go away to your own country and forget us. You say you will come back to Albania, but you never will. It is easy to forget when one is far away; the mind changes. A mind is like the water in a river. We will forget you, too. But I would like to keep this night, because it is a very beautiful night.”

“Yes, Rexh, so would I.”

The lights of Scutari were like scattered glow-worms among the trees. How strange it would be to come back into the twentieth century again! Scutari, Tirana, Salonica—Constantinople? No, not Constantinople. I would go back to Paris. It was not so much that I was tired of traveling as that I was filled with it. One must go across the centuries and back, across a great deal of the world and back, perhaps, to know all the strange things that are at home, all the romances and surprises in one’s own self.

The lights of Scutari were coming nearer. Scutari, Tirana, Durazzo, the Adriatic, Trieste, and Venice, and then Paris—perhaps ten days to Paris, the center of all Europe’s intrigues. For a weary instant I felt again the pressure of all those currents which bewilder, crush, and smother the struggling individual—movements of peoples, marching of armies, alliances of nations, the tides of poverty and disease, the tremendous impersonal economic conflicts. Silicia’s coal, Galicia’s oil, England’s unemployed millions, Ireland, Egypt, India—my mind slid away from them all. I was too pleasantly tired, too much under the spell of the Albanian moon—perhaps, now, a little too old—to care tremendously again for movements. They seemed at once too inevitable and too unpredictable to be concerned about.

The three of us were so small on that vast plain, the sweep of the moon-filled sky and the bulk of the blue-black mountains were too vast; simple as an Albanian, I thought of the world as made of little individuals like ourselves, each lonely, surrounded by the unknown, each a little world in himself. That little world was the real world. Externals did not matter. If each of us could only make our own little world clean and kind and peaceful——

“Tired, Mrs. Lane?” Rexh said, softly.

“No, Rexh. Just thinking.”

“Slowly, slowly, little by little,” said the byraktor’s gendarme.