CHAPTER III

DESERT PERSPECTIVE

THERE was once a mine of gold in Peru. Later it became a copper mine, and now they sell the water that collects in the bottom.

I

THE Incas found a rainless desert intersected by fruitful valleys as to-day, each independent, with its own gods, its own king, its own manners and customs, even its own diseases! Each valley chieftain lived upon a platform among the fields, but his villagers lived in the desert, not to encroach upon land capable of cultivation. These Yuncas excelled in the arts of weaving, fashioning metals, and in making pottery.

In the name of the Sun the Incas descended from regions of snow to conquer the desert-dweller, with lofty disregard of the fact that the benign source of all blessings among the high table-lands was the scourge of the lowlands, where water-gods were worshipped. These religious wars changed the face of the country. Valleys were connected by a great highway. Sun temples and convents for the Virgins of the Sun supplanted the shrine of each valley’s chief god. Only one remained inviolate on the whole coast, that of the awful, intangible Pachacamac, who, being a fish-god in his great red temple by the sea, was not an idol, but the Invisible, Unknown, Omnipotent God, who had existed before either the sea or the sun; Pachacamac, he who formed the world out of nothing, the Creator whose image they dared not conceive. His name was mentioned with shrugging of shoulders and lifting up of hands, and he was served with fasting. Unlike Sun-ritual, his cult was a personal one, the inner worship of a people who paid tribute to golden fishes. The Maker of all Things had been conceived by those ancient peoples who, Balboa says, came from the north on a fleet of rafts, when the mountains had the climate of the valleys, and the whole actual coast was under the ocean.

The aura of the Unknown God invested the fish-idol, and the temple was held in such awe that it was not only spared by the Incas, but they even made pilgrimages to the shrine. Shy in the thought of offending the Maker of the World, Inca Yupanqui allowed his golden seaside temple to remain, but erected a temple to the Sun a little above its level. To honor the conqueror, the priests of Pachacamac “appointed a solemn fishing of many thousand Indians, who went to sea in their vessels of reeds.”

Though the fish-idols were ejected, and a convent for the Virgins of the Sun was founded, worship of Pachacamac went on as before. The Incas joined in it, identifying him with Uiracocha of the mountains, but they extorted Sun adoration as well, a fair barter of faith.

Then the priests of the Sun made an idol of Pachacamac, and so it presided until, drenched with sacrificial blood, it was chopped to pieces by Hernando Pizarro and twenty soldiers in January, 1533. A terrible earthquake followed, which Pizarro called the devil’s rage, and triumphant he planted a cross above the looted temple. Pizarro gave the golden nails to his pilot, as a reward for his entire venture. But much of the temple’s treasure is said to be concealed underground, undiscovered to this day.

The temple pile glows against the blue sea in the midst of shimmering sand. Pachacamac lies in its magnificent ruin surrounded by acres of skeletons. For more than two thousand years it was the most famous burial place of the coast. Even mummies were brought from great distances to lie in the sacred ground.

Layers upon layers of succeeding generations have all yielded their excavated secrets, each throwing light on others. Time and treasure-seekers have laid bare the most recent. Histories of great peoples told by their graves!

I stood upon the summit of the broad mound, the temple to Inti, the Sun, built by the Incas above that of Pachacamac, the fish-god. Its crumbling walls, with traces of their brilliant coloring, ended abruptly in mid-air. The headless skeletons of forty-six young girls had recently been found upon the terrace where I stood, the braided cords hanging loosely about their skeleton necks.

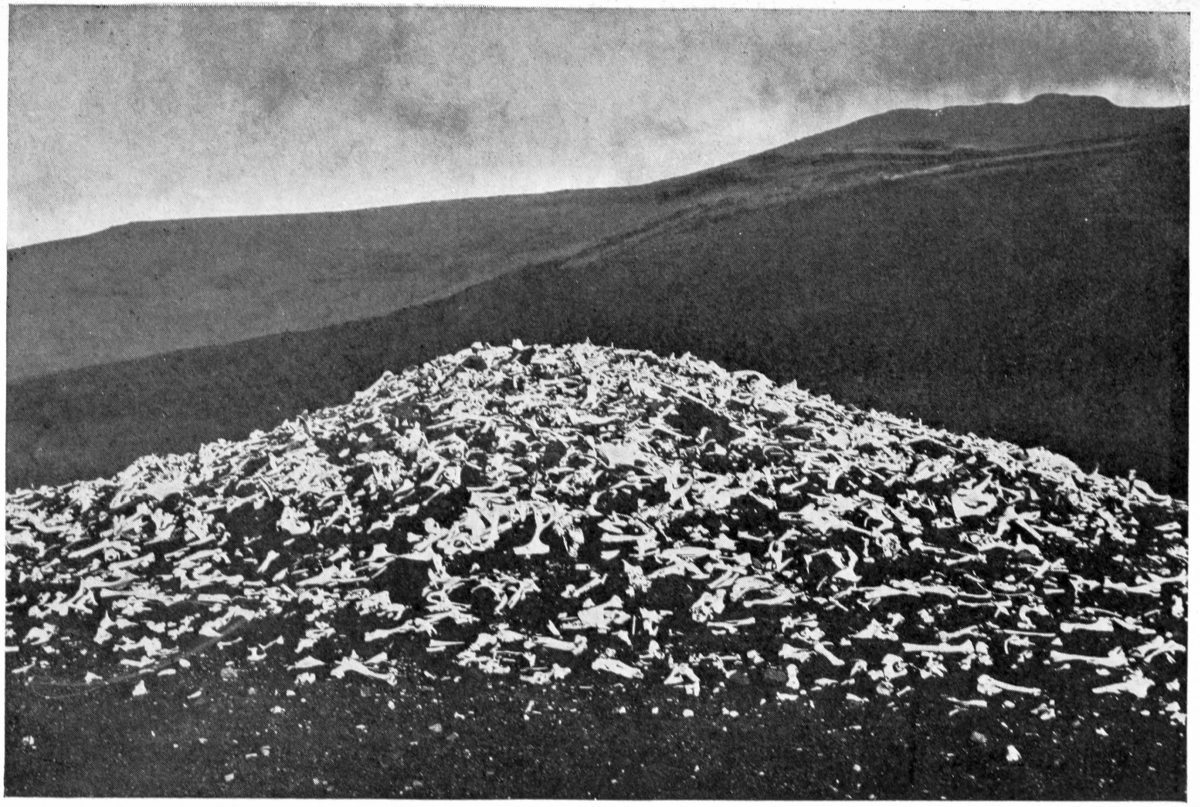

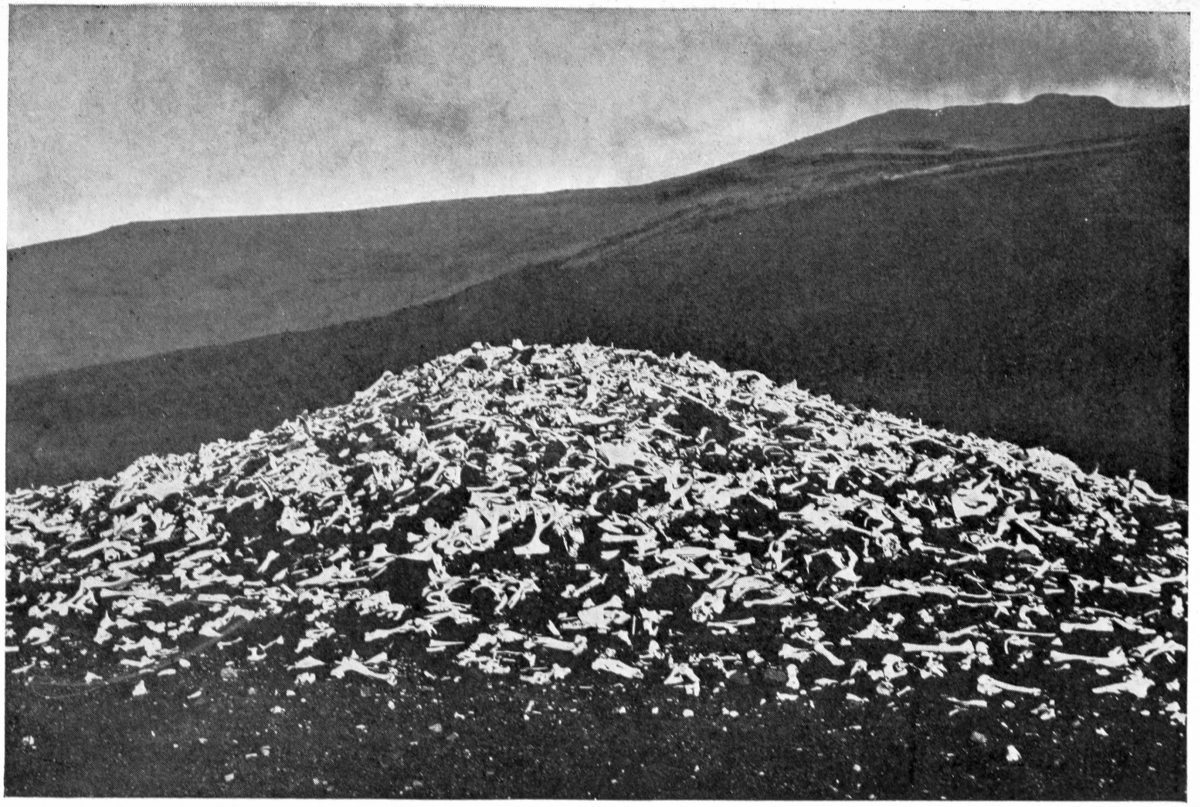

PAMPA DE LOS HUESOS—THE FIELD OF BONES.

Far below stretched the vast field of the dead. I looked out over a desert of round white skulls, with eye-cavities staring at the sun—Sun-worship continued in death. Little flurries of dust rose here and there, as men with shovels turned over the sand, hoping for treasure. Gallinazos, hideous vultures of the desert, paced up and down. Below the convent of the Virgins of the Sun, whose niches only remain, was a small blue lagoon under palm trees. On its reed-edges a white heron tilted about—a curious, gnarled creature, giving an impression of majestic grace.

Between me and the sand-hills rolling up to the Andes lay the silent courts, the great, roofless houses of the city of the dead caving in over its streets of sand. The desert-river separated this sepulchral spot from the valley of Lurin, where cotton-fields and yellowish expanses of sugar-cane were divided by willow hedgerows, with glimpses of water beneath tall mud gateways. The breeze was as sweet as heliotrope hedges could make it and filled with tinkling bird notes.

On the other side was the whole reach of the sparkling Pacific, with its far-off sound of breakers. There is a tradition that the two rocky islands are a goddess, Cavillaca, who cast herself and her child into the sea a thousand years ago. But scientists assure us that the islands were torn away by an earthquake since Spanish occupation. The Incas, they say, had a temple on the islands, then a promontory.

He has not beheld the quintessence of all human suffering who has not seen the face of a hunchback child-mummy. Upon such bodies, doubled up and tied securely into the smallest possible space, whose varnished skin is stretched over their unbending bones, even the tattoo marks still show in designs of their owners’ choosing. They are clothed in finely-woven garments, with sandals, pouches, shell and bead ornaments, embroidered bands, and hair not yet unbraided. Sometimes brilliant eyes stare from empty sockets in the withered mummy-faces, eyes of prehistoric cuttlefish, a symbol of fish worship. In some of the skulls are dents made by blunted points of stone weapons.

One mummy sits in the attitude of a toper about to drink, with a monkey on his shoulder—for pets of the dead man accompanied him on his journey, his dog or parrot sometimes mummified at his feet. The men have their slings and fish nets, the women their spindles, needles of cactus thorns, and every implement of household use, the children their earthenware dolls. All have their little gods and talismans. There are pots of provisions, too, with lids to keep out the thin finger of time, jugs of chicha (a beverage distilled from maize), and ears of corn in nets from which they have never been removed since they were put in by hands turned to dust a thousand years ago.

From the grave of an apparently great official with his treasure-jars, was taken only the mummy of a puma, yellow feathers on its head, a gold plate in its mouth, gold and silver bangles on its legs. It had a necklace of emeralds from the north, and its tail was full of golden feathers from the mystic jungle beyond the mountains.

Recently X-rays have been applied to mummy-bundles, which show other skeletons within as well as the one who had died, skeletons of those who, when those winding-sheets were adjusted, were still alive. Gruesome sacrifice!

Pachacamac has furnished museums all over the world and is still one of the most inexhaustible of mummy supplies.

My horse descended carefully to this field of the dead. He picked his way across stepping-stones on which pilgrims approached the lower court of the temple where their year of penance before entering was to be spent. A step, and there was the sound of crunching human bones. Sand filled the skull cavities. They shattered like fragile glass as the horse’s hoofs clattered across them toward the ruined city. The sand was pulverized bones. Bits of cloth and pottery attracted the collector’s eye, or a deformed or trephined skull.

The city walls are twenty feet thick. Their ends and their beginnings are lost in sand. Marks of fire show here and there, and traces of forgotten industries. Flights of stairs lead down from the tops of walls, over which was the only entrance. The roofs were made of reeds to let through necessary air and light; none were needed against rain.

Swallows, “dovelets of Santa Rosa,” flew over from the green valley of Lurin. Bats and little owls, always in pairs, inhabited the ruins, and lizards basked in the blinding light and enjoyed the quiet. Under the cactus lying loose upon the ground there is sometimes a small black spider whose bite takes months to cure. Its inhabitants emphasize still further the uninhabitability of this scorching desert.

II

ONE other center of power confronted the Incas in the coast valleys, the city of Chanchan, belonging to the Chimus.

In the kingdom of the Grand Chimu, Si, the Moon, was worshipped. It appeared both by day and by night, which the sun was not able to do. The Moon raised the tides; did such power not demand sacrifice? On special occasions the Chimus offered to it small children wrapped in brilliant cloths.

The ocean was the medium through which their Moon-god chose to demonstrate its power. As it nourished them with its fish, scattered by the fish-god Pachacamac through its waves, they strewed white meal upon its surface as a form of worship; incidentally to attract a large catch of fish. Ni, the Ocean, symbolized water, the greatest need of a desert land. It was also their only means of communication between the desert valleys, as they plied up and down upon the “silent highway” to collect tribute. Their boats were made of reeds tied together, and they sat upon them as on “horseback, cutting the waves of the sea, and rowing with small reeds on either side,” as Father Acosta explains. Sometimes they had square sails of grass. One may see these boats of bulrushes upon the shore, for they are still in use, their long, curved beaks leaning against each other like stacks of mammoths’ tusks.

The water cult of the Chimu included worship of fountains, flowing streams, and of their goddess, “She of the Emerald Skirts.” The worst criminal was a water thief, he who turned the stream aside from his neighbor’s field; and the Grand Chimu was overcome at last only because the Inca was able to cut off his water supply. Mild Tupac Inca Yupanqui, who ruled the mountains as the Grand Chimu controlled the coast, preferred victory without bloodshed, since his were religious wars to spread the worship of the Sun.

Sun-worshippers and Moon-worshippers, living side by side, struggled in mortal conflict, but the Sun-worshippers prevailed; and when, after a few generations, the Spaniards, eager for bloodshed, came to conquer the Sun-worshippers in the name of Christianity, the great city of the worshippers of Moon and Sea was gone. They could glut their desire only on hidden treasure in sepulchral mounds.

Mochica, the language of the Chimus, was so difficult that no grown person could learn it. Here and there it was spoken as late as the seventeenth century, and to-day near Eten, “where the sun halted at his rising,” there are elements of it left in a curious dialect, spoken by a little community of Indians whom no one can understand. They braid Panama hats of finest straw. Their huts are almost without furniture, they wear no shoes, and dress always in mourning; but they wear flowers in their hair.

An Augustinian prior, Calancha, collected traditions of Chanchan, that great city of the Chimus which covered twenty square miles. He tells of the processions to the Moon temple, when the Grand Chimu, wearing the jeweled diadem, in robes of feather-mosaic as fine as warp and woof, was carried in his litter by courtiers, surrounded by musicians, minstrels, priests, and warriors with lances and long waving plumes.

The mounds scattered in fragments through the desert were terraced pyramids in those days, the walls upholding them brilliantly painted and richly embossed. Traces can still be seen of their paintings of wild birds and animals, and step-patterns like the pyramids themselves. Vines of the passion-flower drooped their fruit over the garden walls upon the terraces, for water ran to the very top. Even the avenues of trees had individual nourishment from the distant mountains through a lofty aqueduct, the most amazing accomplishment of an amazing people. In the labyrinth below worked the designers, dyers, potters, weavers, and the gold-and silver-smiths, expressing the florid taste of the Chimus.

These sea-worshippers, fish-worshippers, made fish-gods of gold. In Chanchan their small fish-god has been found, worth three million dollars. With it were gold bowls, little figures of fish, lizards, serpents, and birds, neck and arm bands, scepters and diadems, and emeralds from the north. The larger fish-god is yet to be discovered. Manuscripts describe conscientious attempts to unearth it.

The race has vanished; vast Chanchan is gone. We are not even sure what this great people called themselves. Their gold and silver ornaments have long ago been melted into European coin. Traditions of their wealth and magnificence came only through their conquerors, who themselves had no written language. Were we to believe only Inca tradition, all the Yuncas of the coast were savages, given up to unnatural sin. Fortunately there are vestiges of their pyramids and labyrinthine interiors of their temples and palaces, bits of their pottery, and patterns of their cotton fabrics. There are, too, fragments of their marvelous irrigation system, a dumb reminder to Peru that present needs were once supplied by the intelligence and industry of an Indian civilization.

A bush with many-colored clusters of flowers joined together like a bunch of grapes grows not far from the site of Chanchan. It is said that each flower has a different shape as well as a different color. The name of the bush is the “Flower of Paradise.”