CHAPTER II

DESERT QUALITY

A CERTAIN herb lives for years underground in the desert; it feels no necessity for a leaf-existence. Yet if the parched roots are reached by water, they expand toward the sun in lovely bloom.

Up from the shore stretches the bare immensity of desert, ending in one tremulous horizon with the ocean, and with the wilderness of mountains against the pulsating sky at the other. It is the Land of Light. All sensation of color is lost in this great sensation of light, an ardent light “shining through things, not on them.” Even the clouds expire from excess of light. It reduces all colors to mere hot vibration. The translucent mountains swim in a sea of light, reflecting from it as from wide stretches of water. Though sensation of color is lost in light, their huge forms are distinct in the radiant atmosphere, but unreal as if half-veiled.—One attribute of mirage is absolute clearness of outline.—Insignificant details emerge, but they rouse admiration only because of the light investing them.

The whole wide desert culminates in illusion and mystery of distant outlines. Everything floats in it, as it sweeps over from the opalescent mountains. A cross in the midst of the shelly sand, “protruding through thin layers of mirage,” marks the spot where a greatly feared bandit was killed. Skulls are heaped beneath it, with matches and half-burned candles.

Water being denied, the desert is soaked with sun. It is the Land of Heat. No plant grows in the scorching soil, no animal can endure it. No bird, no insect flies through the burning atmosphere. Each object shimmers until it seems but the reflection of itself. Fire descends from the burnished sky and vibrates in the air and scalds the sand. Yet concentrating a tropical sun, this hot solitude lies between the cold ocean and the mountains, a region of ice.

This desert is the abode of weird phenomena. Sometimes a globe of fire springs to the size of the sun, illuminating the sky for a quarter of an hour; then it dissipates into an infinitude of stars, which wriggle off into bright little tails and disappear.

A slowly moving company, muffled to the eyes, with heads done up like Tuaregs of the Sahara, mincing across the desert on donkeys, suddenly see themselves swinging along over their own heads, as if magnified by a gigantic mirror in the sky. The clouds give back strange pictures of one’s self enlarged and surrounded by a halo or a circular iris, summoning a saint or revealing a fairy. This quality is inherent in Peru, making ordinary moments ornamental.

Near Casma is a hill called “Dreadful,” whose continuous sandslides when the heat is greatest give off a sound of mystery, suggesting heat, like the roar of a distant volcano.

No matter how much the political status of Peru may change from century to century, it remains always the lair of earthquakes. Mines of gold and silver, islands of guano, deserts of nitrate, may be in turn discovered, exploited, exhausted. Earthquakes destroy those who have been enriched as those who have lived beside them in want. Even now earthquakes are almost daily recurrent along the coast. In laying your ear to the ground you can hear subterranean rumblings. Only in the frequency of slight shocks do people feel secure; otherwise they know the underground world is hoarding strength for a fury of destruction. As a traveler of the old time expressed it: “The inhabitants are subject to being buried in the ruins of their own houses at any time.”

The Indians say that when God rises from His throne to review the human race, each step as He progresses is an earthquake. As soon as they feel the pressure of His foot upon the earth, they rush from their huts to show themselves to Him. When the rumbling becomes loud enough to be noticeable, dogs howl, beasts of burden stop and spread their legs to secure themselves from falling, people rush to doorways, and churches are emptied in an instant. Reddish mists steam from the sea, bad odors from the earth; distant thunder—complete wind-stillness. The clouds of sea-birds rise from the earth and fly high, watching an agony in which they have no part. Then a frightful crash, rocks are torn asunder, great masses fall off as islands into the sea, which is still. But soon it turns black, boiling with a smell of sulphur, and many dead fish float about.

Omnipresent, the earthquake is a mystery which no laws can govern, beyond man’s comprehension or control. One never gets accustomed to it. Horror at a first shock only increases with further experience. Earthquake is linked with freaks of nature; it lifts up a ridge across the bed of a stream; it alters the face of the earth so that lawsuits spring up over changed boundaries. It vitiates the soil. Blooming fields wither, crops are lost, and cattle die from eating the scorched grass. The fiery core of earth is nearer the cooled surface than we imagine. But here at least there are no “torments from heaven.” In Peru it is said that lightning is worse than earthquake, emanating as it does from God’s own realm.

Even the climate of the coast partakes of mystery. The clouds hurrying from the Atlantic have drenched a whole continent of jungle in tropical downpour, and before they reach the desert, their last drop of moisture has been wrested from them as snow—drained dry by the Andes. The tropical sun heats, and the Antarctic current bringing its icy winds, cools. Sometimes one predominates, sometimes the other. For the red-hot desert can also be cold! The low-hanging garuas, the ocean mists of half a year, chill the desert and cling to the base of the mountains, fading lighter and lighter up and away from the black rocks where white surf is breaking. Such are the facts of the case, but it has been thought that the original god, Con, was responsible, for once in anger he deprived this desert coast of rain.

The desert is majestically empty, a great “vision of nothing without perspective.” Yet its mere emptiness suggests breadth, backward and forward, up and down, both in time and space. An unheard silence lies between the empty horizons, perfect except for the “great, faint sound of breakers,” the tumble of an unused ocean of water, which destroys without moistening the desert shores.

It seems lifeless. Harmless and peaceful at least, it presents nothing to be destroyed by sun-blight. It remains, as it apparently always has been, the realm of death—though even death presupposes life before it. But disturb the desert, and a thousand forces spring into action, furiously attacking the intruder. The heat of the sun assumes a ghoulish love of destruction, and at night the stars look down upon a creature shivering with fever, reeking with wet in this desert place. Possessing all fruitful ingredients within and kindly elements without, the desert sleeps. It needs only one thing to burst into life.

A mysterious river springs forth full-grown. From what glacier or clear, icy fountain up on the frozen puna may it not have issued? And then, after a mysterious incubation, it returns to sparkle here in the light, and in the leaves and flowers which the dampened earth is ready to produce.

There are traditions that sometimes a vagrant shower escapes from the magnetism of the mountain-tops. The flowers waiting just beneath the surface spring up like bloom over the June earth. The water was a shower of bluebells! A fugitive vegetation greedily spreads, quickly as it disappears with the passing of the water. In some places cotton grows to the height of a horse’s head, a luxuriant crop, too unexpected for harvest. This brilliant life lasts a week, perhaps more, and then lapses. Where do the slumbering flowers conceal themselves? Where, indeed, does the pansy get its coloring matter?

The desert of Peru is varied: toward the south the coast is strewn with borax, white upon the cliffs; toward the north petroleum gushes from beneath it. Upon the red plains of Huacho are the salt lakes of Pampa Pelada, reflecting the sun in a thousand colors. “White dust-whirlpools dance on its white floor.” Its banks are scattered with the bones of animals which have come there for salt, and its perpendicular cliffs are haunted by flesh-eating birds. There, gnarled gray shrubs “loom as if carved out of clay.” Beyond, the desert is coated with nitrate; yet here it seems but pulverized bones, beneath acres of white skeletons bleached by a thousand years—gaunt testimony to its desertdom since prehistoric Indian races struggled to make it blossom.

In the Pampa of Islay the desert takes on a terra-cotta hue. Whirlwinds progress from hollow to hollow. Above the purple mountains, shading away from the red desert, bright blue peaks are snow-covered to set them off from the sky. Fog shadows drop darkness here and there over their barrenness. Even the mist has a poetry of contrast.

Across the plain a constant ocean wind sweeps fine white beach-sand along with waves of color, no less real because impalpable. Its pilgrimage of a thousand years toward the mountains is uninterrupted, for the wind blows always from the southwest. It causes the rippled waves of sand which it brings along to assume in traveling a crescent shape—the wandering médanos.

Sometimes larger dunes overtake smaller ones, which, so absorbed, become firmer in shape as they journey toward the mountains. Should two collide, they are shivered, then blend in a new crescent, usually to separate again.

Growing from a network of roots within the moving dune, the snowy heads of a small plant maintain themselves just above the sand as it drifts over the hard plateau.

The médanos are scattered as thickly as the crescent shadows of some vast eclipse, a labyrinth of nature. They are as mysterious as “mushrooms growing in rings, marsh-fires which cannot warm, or the shrinking of the sensitive plant.”

The sand drops constantly over the acute crest. From all about come soft sounds, an overwhelming minor music, almost inaudible. Were you in a forest, you might think it was the soughing of the wind through the branches or the shuffle of locusts devouring a tree.

These playthings of the wind have been called symbols of the Moon in the land of the Sun, since nothing in Inca days could dissociate itself from either; a crescent Moon humbled by the Sun’s anger, allowed to possess her former fullness but a day at a time, doomed to be obliterated over and over again.

The worth of anything consists in the fact that through it can be seen something more beautiful than itself, something to which it forms the setting. Words are mere points of departure. What limitless excursions can even one word suggest, into countries more wonderful than any created by a remote if consummate artist! And what an intimate happiness is found there, which no one else has felt nor could describe if he had!

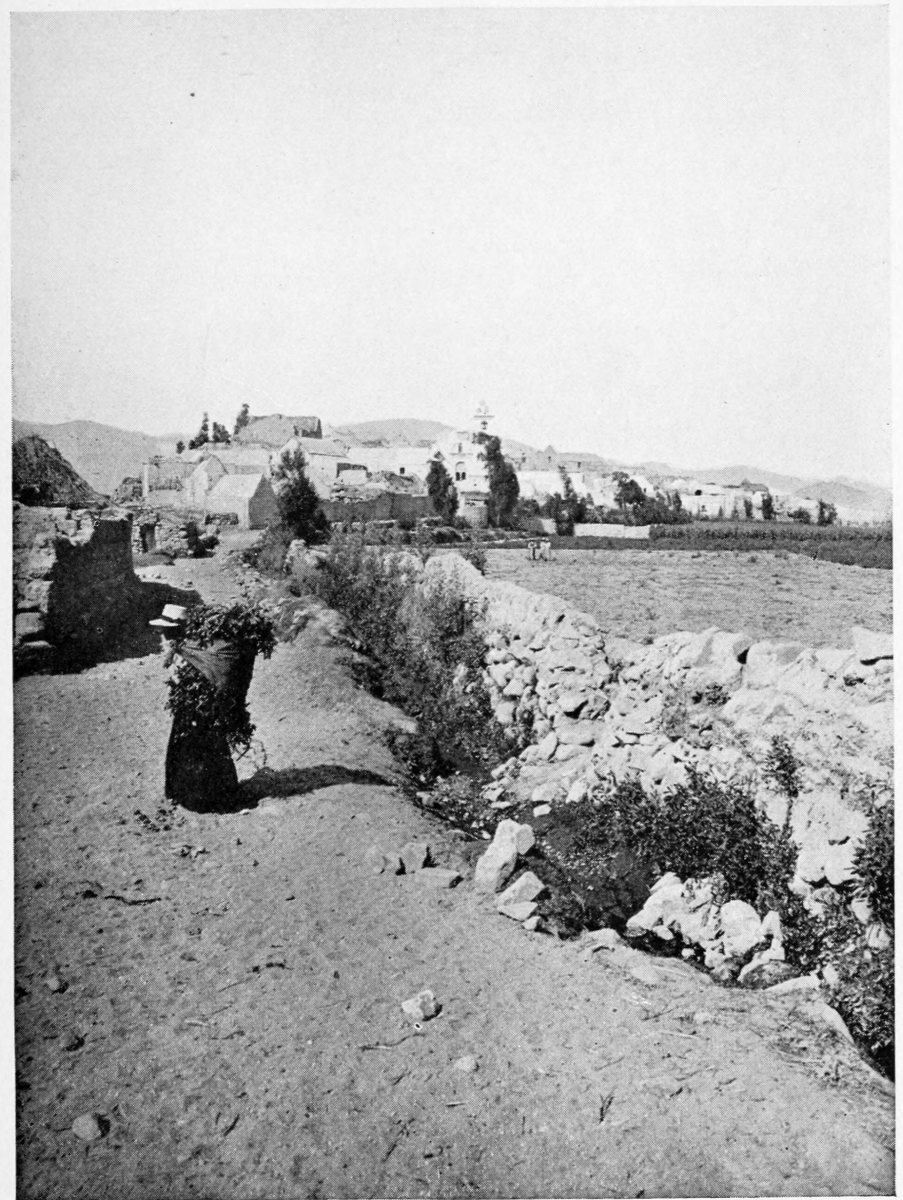

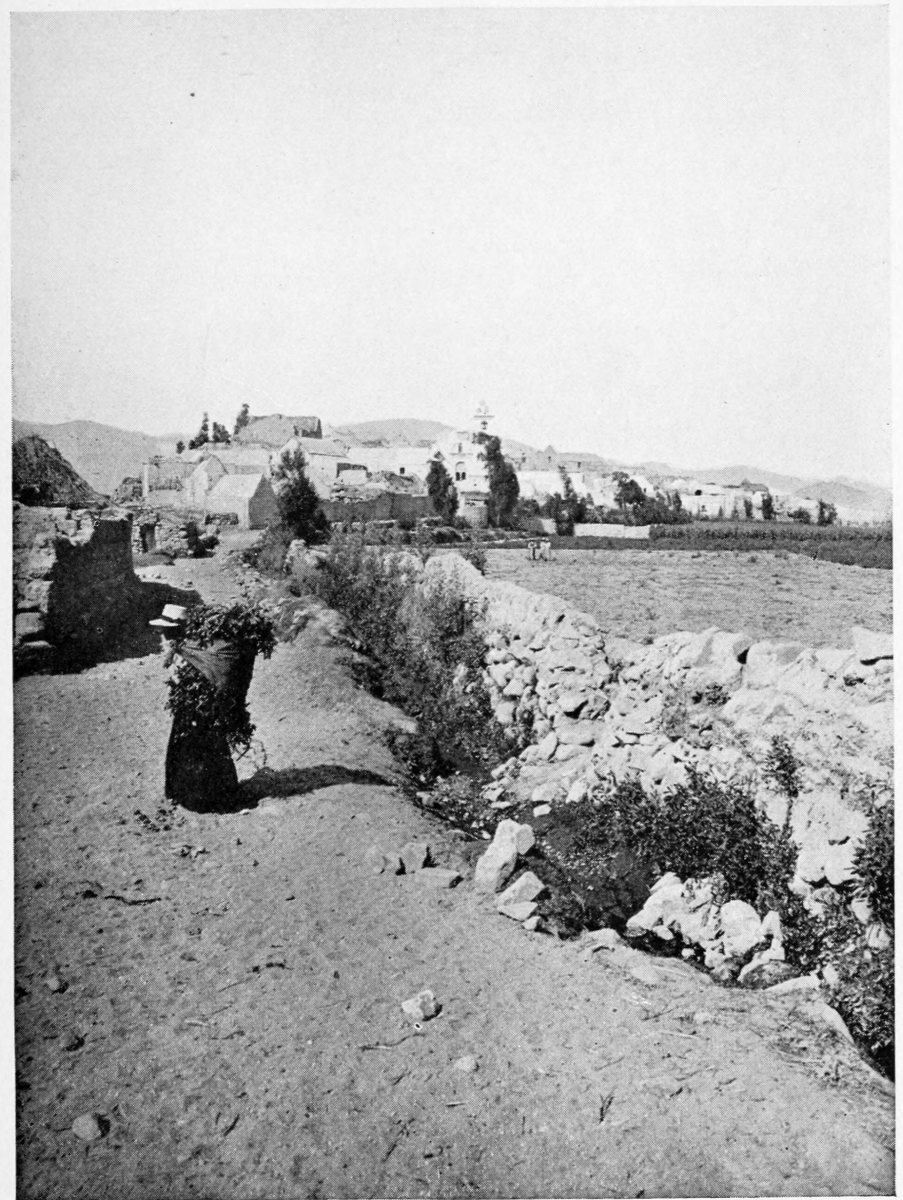

SACHACHA, A TYPICAL VILLAGE OF PERU.

Wherever rivers descend from the mountains, green garlands are slung across the desert. No wonder the river was a god to the desert-dweller, bringing with it meadows and gardens. Where only dust has been, acres of cotton, bright-green sugar-fields, and dark orchards lie between mud walls and willow-shaded lanes. Herds graze upon alfalfa steaming in the sun. The yellow plaster terraces and balconies of haciendas among their banana groves are shaded by cascades of glowing bougainvillea. But wherever water is, fever follows. Disease clings to the green spaces. Even sickness cannot abide in the desert alone.

Huge, pyramid-like mud structures spring crumbling from the soil whose modified form they seem to be, temples and palaces of former days, each with its legend. The ruins are inhabited by weird iguanas and “haunted by those birds of ill omen that only nest in ruins.” Mounds of treasure, too, linger along the desert, and fragments of the paved road of the Incas.

A gold bell was once buried in Tambo de Mora. Older people have heard it tolling on quiet nights. Some say it rings from the top of a hill, some, from beneath the ground. To be sure, bells were not known to ancient Peruvians, yet a company was properly financed to hunt for this bell of gold.

Submerged or enchanted cities exist on every hand. A mystic race of dwarfs live in the Andes. They guard a vault of buried treasure. An Indian who declared he had seen it became so terrified at the extent of the riches that he fled, not forgetting to mark his path. Yet frequently as he had followed the trail to the very spot, he could never again find the cavern of glittering jewels: it had sunk completely out of sight—“You can see for yourself, Señorita, that it has, if I take you there!”

Legends of prehistoric days take on the garb of myth, when giants came over the sea to Peru long before the memory of man. Wishing to provide themselves with water in the desert, they excavated enormously deep wells, still undeniable evidence of their dominion. Moreover, their bones of incredible size have been found. Garcilasso says a piece of one hollow tooth weighs more than half a pound. Their footprints have been traced as far as Patagonia. For their sin they were destroyed by a rain of fire.

Maui, too,—the Polynesian god who caught the sun with cords of cocoanut fiber, who lifted the sky and smoothed its arched surface with his stone adze, who made the earth habitable for man and then created him, and who now divides his time between fishing for islands with a hook which is called the Plume of Beauty, and resting in the form of a small day-fly upon the under side of a flower,—Maui, who belongs to the length and breadth of the Pacific, once visited Peru.

Upon this coast lived aborigines with flat noses, fishing from boats of inflated sealskins, and sleeping pell-mell in sealskin huts on heaps of seaweed, “tall, cannibalistic fishermen ... who used bone utensils, made primitive pottery, nets, and fabrics of osier.”

Here lived the contemporaries of the Incas, Yuncas they were called, “dwellers in the hot lowlands,” distinct from those of the highlands, with their hideous thoughts painted on earthenware jars, and their hazy conception of a single god, their pragmatic worship of him by means of anything which he had made for their support and comfort, and their sacrifice to him of his greatest gift, human beings.

Fancy is free to play along geologic or human history. Bones of mastodons as well as sea-bottom shells are found in the desert. Vanished races have embellished it in passing. Man has but added to the mystery of nature. Yet after such lapses of time the two are mingled indistinguishably.