CHAPTER I

ALONG SHORE

THE surface of the ocean is unruffled. Only the heaving of its great body suggests the power beneath. But when it confronts the desert cliffs, backed by the world-weight of the Andes, the force which has been gathering all the way from Australia, so mighty that it can be compared to nothing but itself, snarls into uncontrolled fury, rebellious, but acknowledging the limit of its power.

The “Peaceful Ocean” lies next to a land of geological unrest; the coast rising, subterranean torment breaking out in earthquakes, hurling cliffs into the sea. Even the busy modern port of Callao partakes of the mystery of this elemental land. The white ships anchored in the clear water of its harbor gradually turn dull brown. Might it be the crater of an extinct volcano?

No wonder the people on such a shore build bamboo cages plastered with refuse and mud to live in, temporary for them as the present stage is transient in the history of the land on which they live. Their object-lessons are warring natural forces. No wonder they are brutal, slinging cattle on board steamers by the horns, casting a stone between the eyes of a bullock to make him turn around. Even their little children play at bull-fights with horns of defunct cattle. The soil of this “sea-gnawn” shore affords not one necessity for human existence, not even a drop of water. There are no real harbors, only niches in the jagged coast. But few lighthouses indicate danger, and the desert is chilled by winds from the Antarctic pole.

Far out, a low cloud is skimming the surface of the gray water, advancing in waves of blackness. From one end a shower falls; at the other, a column rises from the water to meet the on-rushing mass, “a great oval, rolling forwards over the sea.” It comes nearer and nearer, till the shore shimmers as through heat waves. The quiet is complete except for the noise of millions of laboring wings.

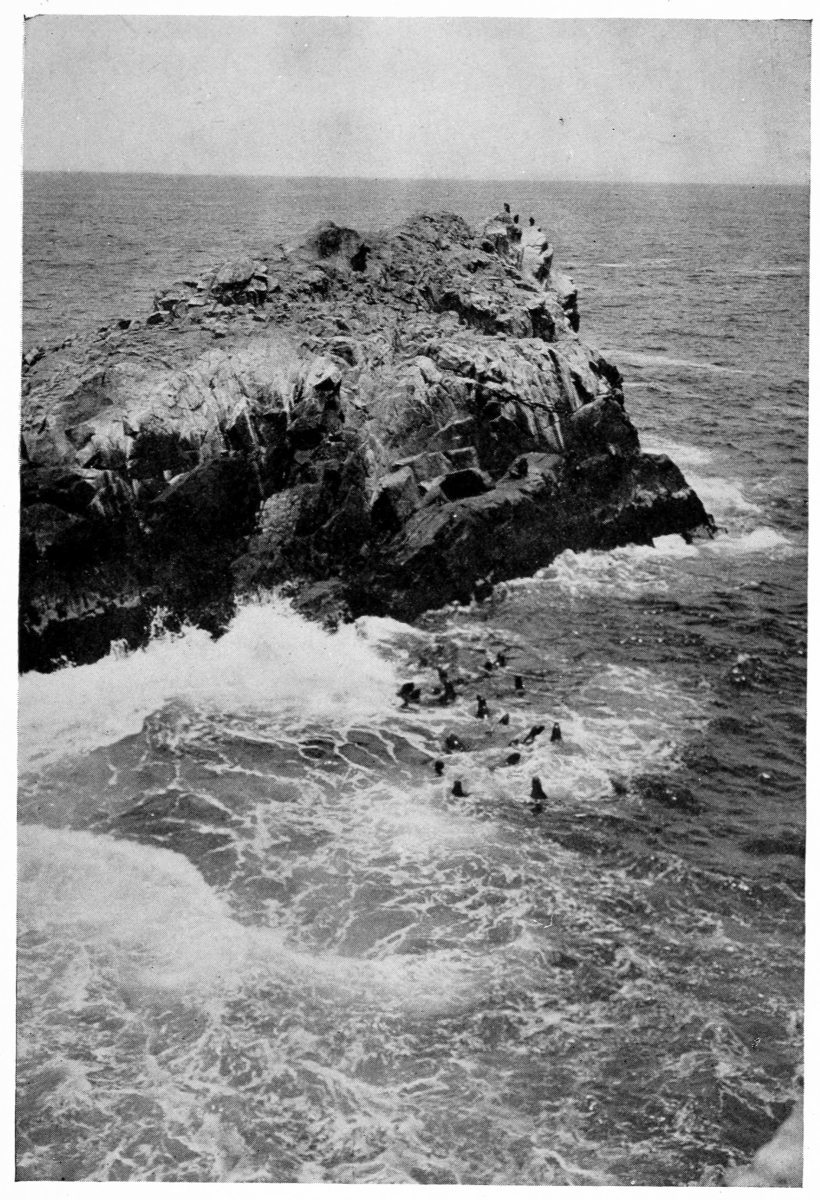

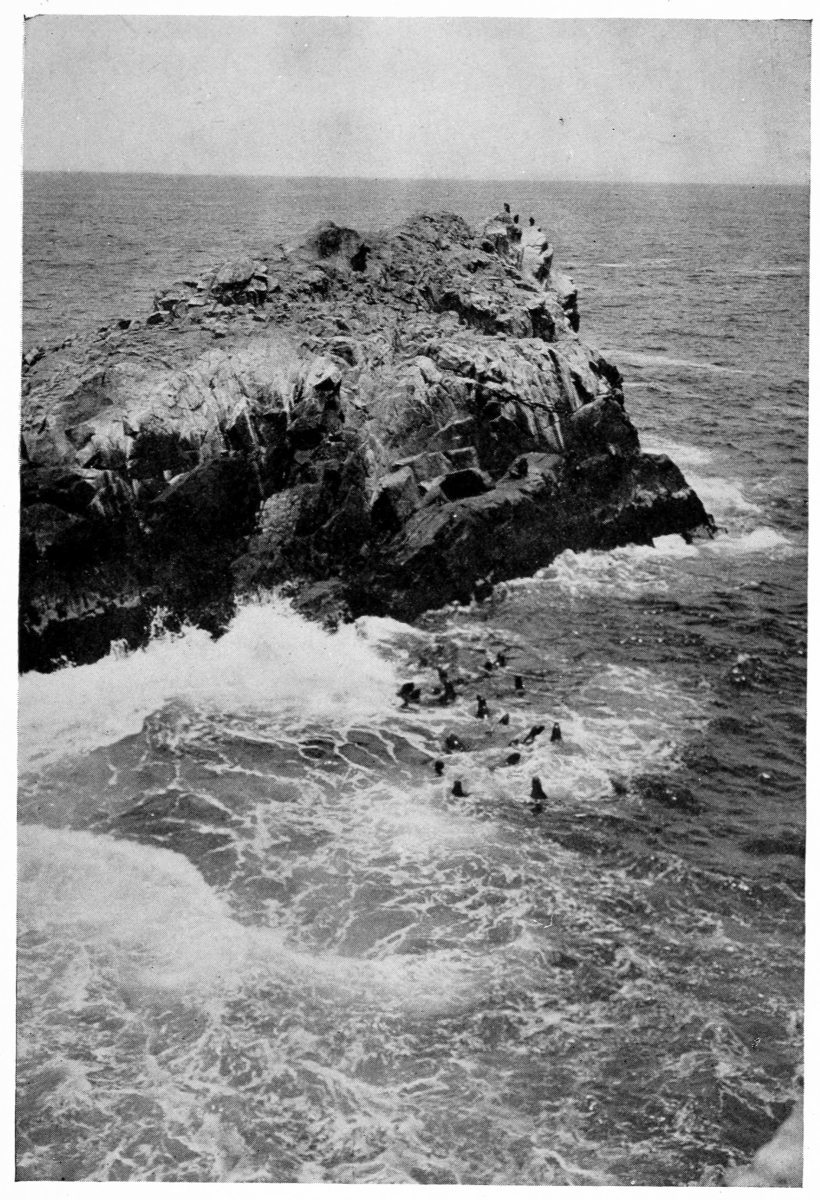

SEALS OF THE PALOMINOS ISLANDS.

A cloud of birds! Now they fall to the water with close-clapped wings, hundreds at a time, each a tiny splashing fountain. Their hunger is insatiable, but not because food is lacking, for the swarms of pilchards beneath the waves are vaster than the armies of birds which pursue them. Ancient Indian races enriched their irrigated fields with these little fish. A curious, tawny jewel is found upon this shore, known as “fishes’ eyes.” Might they be fossilized eyes of those fertilizer-fishes?

The appearance of this coast could not have been different in antediluvian days, with the screeching birds and the mammoth terrapin off-shore, those associates of the dodo.

The birds fly out at sunrise and spend the day in fishing, resting upon the waves when they are tired, and at sunset return to their giant stone islands for the night. Alone, the call of a sea-bird would be lost in the fury of the meeting of cliff and sea. But as a mass of white gulls can assume blackness by mere quantity, so their mingled voices can take on an overwhelming poignancy of sound. Louder than the crash of breakers, louder than the barking and snorting of the bald, fat seals loping over them in droves, surges the great cry of the birds, as, in a shower of wild calls diverse as themselves, they settle upon the rocks: pelicans, cormorants, mollyhawks, gannets, sea-mews, gulls, osprey, occasional tropical flamingoes lost among ice-birds and stormy petrels, wild ducks, Inca terns, and the weird, amphibious “bird-child,” which tries to stand erect, fluttering its cartilaginous wings, braced by its indistinguishable tail. All the birds of the ocean gather here, from sandpeeps to albatrosses, a surfeit of life to accentuate the barrenness of the shore. They are multiplying every year their already limitless myriads, useless to man as the savages of the interior, without commercial value now of any kind, yet not annihilated on that account. It is said that all are souls of sailors lost at sea. In each stormy petrel a lost apprentice lives again, in each pelican a boatswain, in each mollyhawk a chief officer, in each albatross a sturdy old captain.

One is tempted to write of the romance of the sea-birds of Peru, if romance has in it any of the fascination of waste on a large scale, for like barrenness, waste must be on a large scale to be picturesque. Where is the impertinence of it so overwhelming as in nature—her spendthrift production of unused powers, and the daring of her destruction?

A German scientist, investigating the guano interests, reported eleven million birds on one of the Chincha Islands, for these are the guano birds, and these wild, craggy islands the Guano Islands, a jewel-casket of Peru, which now abandoned, emptied of its contents, stands wide open, staring vacant in the sunlight, that its owners may not forget its former fullness.

Under the stimulus of pure guano a plant will spring to mammoth dimensions, lavishing blossoms and fruit. Ancient races, even the foreign Incas, realized its magical endowments and made laws governing its use. But land enriched by guano into immense fertility lapses after a while, barer than before.

A few sailing ships, hoping to glean poor remnants of this accumulation of the centuries, still huddle as close as possible to the black rocks, which, because of the quantity of that very fertilizer which has distinguished them, are made repellent to life of any kind. In this laboratory of the strongest fertilizer, there is not the slightest trace of vegetation—Peru in paradox.

The sunset blazes through the fissures and shoots shafts of opalescent light under the great stone bridges toward the mountainside of the candelabrum, veiled in a hazy shimmer. Defiantly gorgeous it is, all but the young moon which nestles among rushing scarlet and black clouds.

A giant candelabrum, at least four hundred feet long, is hollowed deep in the rock of the sheer volcanic headland above the sea. Its trenches do not fill with drifting sand, though the natives of Pisco make periodic pilgrimages across the bay, just to be sure. Some think it is a sign of royalty, a flaunt of the Incas, or the boundary-mark of a conquered kingdom. Some say it was a warning made by the Spaniards after Pisco was sacked by English freebooters in the seventeenth century, for though now over a mile inland, it was then a coast town. Such is the equilibrium of the Peruvian coast! Others call it “the three crosses,” the life-penance many years ago of a Franciscan friar named Guatemala.

But a symbol does not for mere inquiry give up the secret of its hidden mystery. Doubtless the origin and purpose of the Candelabrum of Pisco will never be known.

A few small, square, purple shadows mark a town, put down at random in the desert beside the sea. Some houses are made of the ribs and jaws of whales. A conspicuous white building, a little removed, is for sufferers with bubonic plague. Crosses surmount hummocks round about the town. People are making pilgrimages to and fro. And over all, white-headed vultures are wheeling. They spread their wings and cry in the silence.

Dust covers the little city, clustering about a market-place of sand. A fountain without water mutely occupies its center. Lamp-posts without lamps surround it, and the mud houses are without windows. The cathedral towers have no bells. Strange plaster figures are sculptured upon the façade, and infants with hands put on backwards hold up the portico. Beyond the door with a two-inch keyhole are Virgins in pink silk and gold tinsel, saints with rows of parallel ribs, angels with gauze wings, towering altars of gingerbread work, artificial flowers, and silver-paper fringe.

Glossy-haired women, their black mantas (head-shawls) thrown back, drag stiff skirts through the dirty sand. Half-naked children gnaw at the inside of long bean-pods. Mangy dogs with dusty skin and a sparse sprinkling of yellow hair slink into the shadows. Black goats and their attenuated kids search about in the sand for something to eat. Men and women file out of black interiors, carrying gourds full of brilliant edibles. Meal braizes over a low fire on the sand; a woman crouching over it whips the flame with the end of her long hair. From time to time, to make a brighter blaze, she picks up pieces of wood with her strong toes. Near by struts a blue-eyed bird. It is a huerequeque, the household scavenger. Bits of cloth hang about his tall knees. The woman explains that they are trousers intended to keep him warm. She is sorry I could not have come a few days later, for she is about to make him some new ones for summer, of lighter quality, with lace edges.

The market is held in the bed of a “river,” no less dry than the surrounding desert. Old women behind piles of tropical fruits, guayabas, pacays, ciruelas, gossip to a whir of small mandolins. Heavy-browed men in flapping sombreros drink thick liquids and purchase pats of red and yellow picante (a highly seasoned dish). Groups of pack-horses with silver bridles are tied round about the market.

But surprises are lurking in these coast towns. Behind heavy, unexpected doors, the single affluent family of the town receives in a peacock-blue salon. There is a lady in brown, with trimmings of blue velvet and cotton lace, and a perpendicular yellow hat. Another is in purple velvet, with swan’s-down hat and photograph brooch of her sister. A third, wearing green velvet, a salmon colored hat with red roses, and holding a pink silk handkerchief embroidered in lavender, sits purring beside her red-faced German fiancé. The carpet is red, the furniture covered with brown brocade; there are statues of carved alabaster with gilt edges and pink cuspidors. Gold mirrors, chromos of Venetian court life, and pasteboard calendars of bygone years hang upon the walls. The Spanish tiles of long ago are painted over.

Farther up the street a door may open upon a wilderness of vicuña rugs as tawny as a lion and softer than moleskin. Shawls of tan-colored wool, silkier than Liberty fabrics, lie about. One is not surprised that vicuña wool was reserved for royal use in Inca days, nor that blankets of it were sent by the conquerors as offerings to Philip II. There are little foot-warmers made of vicuña fur and chinchilla skins, wiry penguin skins and a deafening noise of singing birds in cages. A black-eyed girl with hair like tarred rope stands making cazuela (a thick soup) and paring guavas. She claps her hands, and many doves fly in to peck the crumbs from her lips.