CHAPTER 7

THE BLACK GIANT

Tall pine forests shade much of the eastern third of Texas and, for generations, farming and the timber industry fueled the economy across much of the red-dirt part of the state. While most East Texas families managed to get by growing cotton and corn, some men accumulated vast wealth in the cutting and milling of timber.

One man who grew rich converting pine trees into lumber was Captain John Martin Thompson, a Georgian with Cherokee blood who came to Texas in 1844 from what is now Oklahoma. Settling in Rusk County, he prospered. Near the end of his long life, rather than trust the division of his sizable estate to a sheaf of legal papers constituting his last will and testament, Thompson decided to divide his assets among his 12 children. Gathering his brood, the old Southerner offered them a choice: Gold or land.

"The boys decided they would take the gold dollars," a grandson of Thompson recalled.

But hoping to be helpful and earn her father's approbation, Thompson's daughter, the youngest child by his first marriage, reacted differently than her brothers and half-brothers.

"Oh, Papa," she said, "just give me the land for my part."

Lou Della Thompson, who indeed got a portion of her father's Rusk County acreage, later married William R. Crim and they made a modest living farming her land. In addition to their crops, they raised four children-three boys and a girl. The oldest was J. Malcolm Crim. Everyone called him Malcolm.

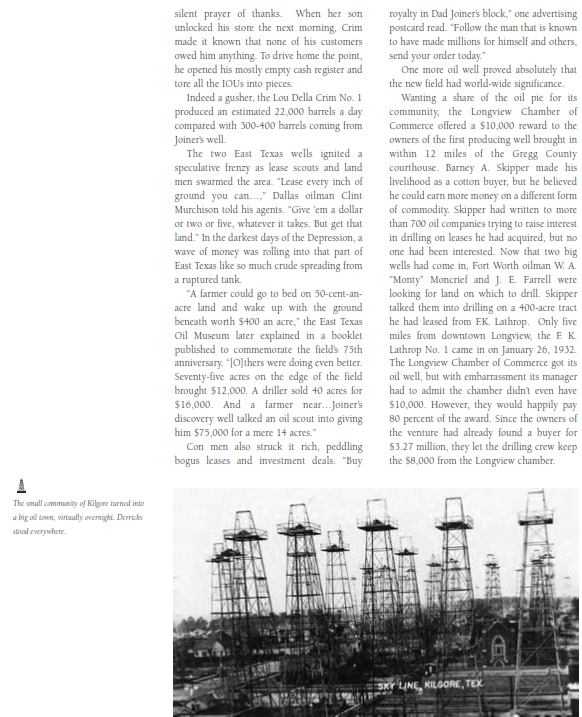

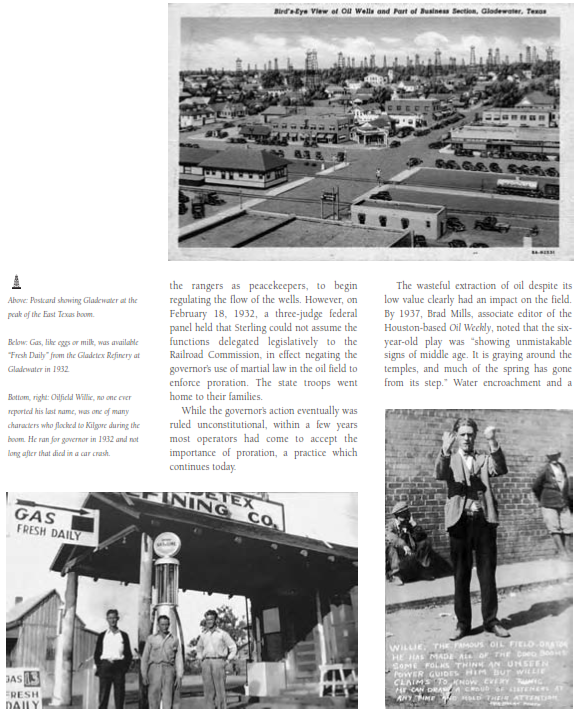

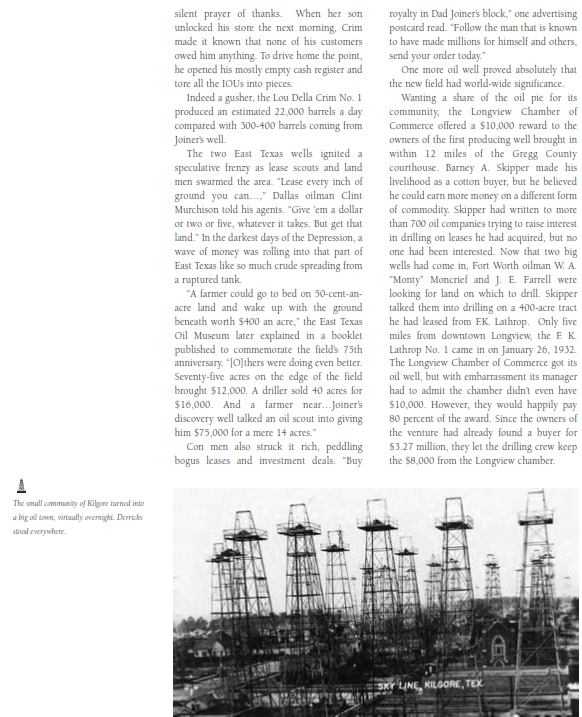

By the 1920s, having migrated to nearby Gregg County, Malcolm Crim owned and operated a general store in the small town of Kilgore. Soon after the Great Depression came on, Crim found himself struggling to stay in business. Most of his customers could only offer him IOUs for food and other necessities and Crim, a devoutly religious man like his long-widowed mother, took the unsecured notes even as he watched his own finances shrinking.

Maybe folklore, maybe true, the often-told story is that one day a Gypsy fortune teller came through town. For 50 cents, not an inconsequential sum back then, she offered to reveal a customer's future. Crim took her up on it. The woman did seem to know a lot about Crim's past and present, but it was his tomorrow that Crim had ponied up half a dollar to learn about and the traveling woman did not disappoint. She told him she saw his land covered in black oil.

Another sort of gypsy, a mostly self-educated, quasi con man named Columbus Marion "Dad' Joiner gets credit for being the first person to envision a rich oilfield in East Texas. He could quote the Bible or Shakespeare with equal authority and had learned that not all theater has to take place on the stage.

Alabama-born, Joiner had spent much of his life in Tennessee and Oklahoma. Having moved to Dallas, Joiner rented a low-cost office in the Gulf States Building and supported himself acquiring and peddling oil leases. He and his ilk were known as "lease hounds." By 1927 he didn't have much to show for his 67 years but he had no shortage of charm, particularly in dealing with the ladies- especially widows and spinsters. "Every woman has a special place on her neck," he supposedly bragged to someone, "and when I touch it, they start writing me a check. I may be the only man on earth who knows how to locate the spot."

While not a compulsively honest man, Joiner does seem to have honestly believed what he liked to call "an ocean of oil" lay undiscovered beneath the farm and timber land of East Texas. No matter the earlier oil plays in Nacogdoches, Corsicana or Mexia-all in East Texas-Joiner may have been just about the only wildcatter to believe a significant amount of oil could be found in that part of the state. Over the years, various tests in Northeast Texas had failed to produce any oil. The big oil companies now looked to West Texas as oil country, disdaining the other half of the state except for along the upper coast. With national prohibition in full sway, about the only useful liquid emanating from East Texas came in glass jars from moonshiners.