CHAPTER 8

WAR AND POSTWAR

WORLD WAR II

In the latter years of the 1930s, one of the better customers for Texas oil was the island nation of Japan, which had been engaged in a vicious if one-sided war with China since the summer of 1937. The U.S. eventually stopped selling to the empire-minded country, but when Nazi Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, Texas oilmen at first envisioned an increased flow of their product to England and other European countries suddenly at war with Germany. Soon, however, the U.S. would have a critical need of its own for oil.

When radio stations broadcast the first bulletin that the U.S. Naval base at Pearl Harbor had been attacked by the Japanese on December 7, 1941, many Texans not only had never heard of the Hawaiian facility, home of the nation's Pacific Fleet, most had no idea where Pearl Harbor even was.

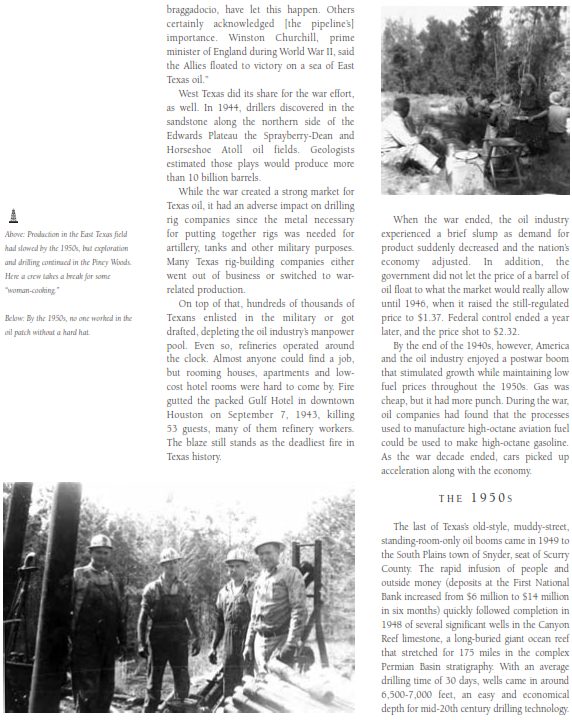

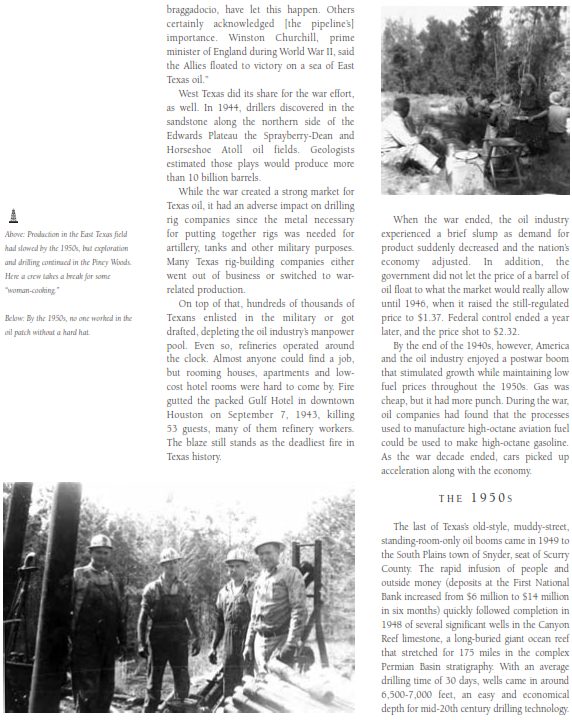

The Texas oil industry quickly became a key component of the war effort. For the most part, competitiveness and even the quest for increased profit went on hold for the greater good. As quickly as possible, oil companies with refineries in Port Arthur, the Houston area and West Texas refitted and expanded their plants to produce high-octane fuel needed for aircraft and butadiene needed for the synthetic production of rubber tires. The big companies pooled their patents and once closely guarded proprietary information to hasten the development of improved refining techniques. By 1942 the government had begun rationing gasoline and instituted a war-time 35 mile an hour speed limit. (Rationing did not happen because gasoline was in short supply; the problem was rubber. The measure was intended to conserve that critical product by decreasing wear on tires.) Assuming a motorist had rationing stamps to use, the cost per gallon remained affordable with the price of a barrel of West Texas Intermediate crude frozen at 92 cents for the duration of the war by the Petroleum Administration for War. Oil companies chafed at so much federal regulation, but most understood the expanded bureaucracy as a temporary necessary evil.

At the beginning of the worldwide conflict, 90 percent of Texas oil reached the East Coast by sea from the Houston-Beaumont area. But in January 1942, wolf packs of German U-boats began attacking oil tankers in U.S. waters, sinking 62 ships in the Gulf of Mexico and sending another 171 vessels to the bottom along the East Coast between Florida and New York.

With tankers being torpedoed within sight of the Texas coast, the German war machine succeeded for a time in impeding the flow of oil to the Allies. Spiraling maritime insurance costs did the rest as shipping companies looked to their bottom line and found it more prudent to keep vessels in port until the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard could clear American waters.

A partial, but significant solution would be an enormous inland pipeline, an engineering feat considered one of the most successful cooperative efforts between industry and the federal government ever achieved.

On August 3, 1942, the big oil companies-working under federal authority-began construction of a 24-inch underground pipeline that would extend from Longview in the heart of the East Texas field to southern Illinois and from there to Phoenixville, Pennsylvania. Some 15,000 men worked day and night on the project. Completed a year later at a pace that averaged nine miles a day, the 1,254-mile pipeline carried more than 300,000 gallons of oil a day from Texas to the Northeast. A second pipeline, this one 20 inches in diameter, paralleled its bigger brother.

Dubbed the Big Inch and Little Big Inch, by war's end the two petroleum lines had pushed more than 350 billion barrels of crude and refined products to the East Coast. Texas oil surging through the world's longest pipelines played a significant role in the Allied victory that came in 1945.

"One wonders why so little is said about this monumental accomplishment," an editorial writer for the Longview ]ournal pondered in 2014. "It is a shame that we Texans, who are known for our