THE

COVER-UP

Edwin Giltay

GENERAL

the

forbidden

book!

The non-fiction tell-all that exposes

a sinister Dutch espionage affair

ONCE BANNED IN HOLLAND

NOW RELEASED IN ENGLISH

1

The Cover-Up General

The Cover-up General

The Cov

The

er

Cov -up Gener

er

a

-up Gener l

a

E

dwin Gi

dwin lt

Gi ay

lt

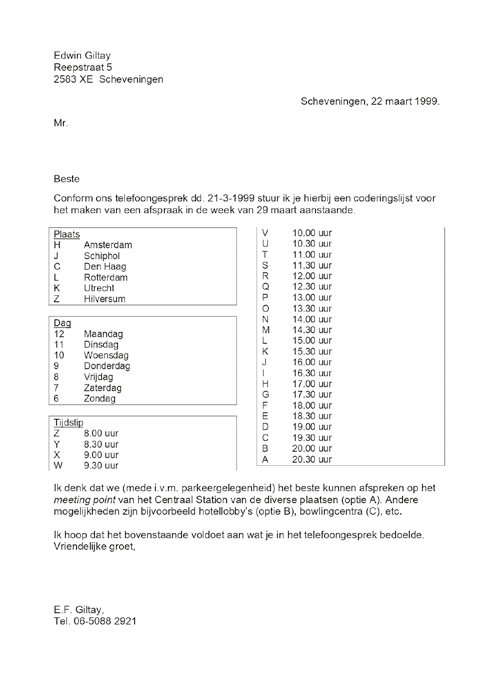

The pdf of The Cover-up General is licensed under Creative Commons

by-nc-nd 4.0. This allows readers freely to download and distribute the pdf in its original form.

Copyright

Edwin Giltay,

edwingiltay@gmail.com

Copyright Epilogue

Hans Laroes

Copyright of

John Melskens,

Author’s portrait

instagram.com/johnmelskens

Photo on front page

stock photo, not the camera roll in this book

Cover design & layout

Edwin Giltay

Editor (Dutch)

Mark Baker

Editor (English)

Michael Wynne, wynnemi@tcd.ie

Translator of

Milan Petrović,

Bosnian synopsis

milance.petrovic@gmail.com

Translator of

Dr. vet. med. Mareike Kraatz,

German synopsis

Mareike.Kraatz@gmail.com

Translator of

Yurri Shynkarenko,

Russian synopsis

shynkarenkoyuriy@gmail.com

Genre

Non-fiction thriller

Original Dutch title

De doofpotgeneraal

More information

thecoverupgeneral.com

Book’s Lifecycle

1st Dutch edition

Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2014

Dissemination ban

District Court The Hague, Netherlands, 2015

Book ban lifted

Court of Appeal The Hague, 2016

2nd Dutch revised ed.

Groningen, Netherlands, 2016

3rd Dutch revised ed.

The Hague, 2022

English translation

The Hague, 2024

In memory of my late grandfather Frans Erkelens,

Colonel, court martial member

Contents

Introduction ........................................................................... 10

Part One

1.

Character ....................................................................... 14

2. Defence women .............................................................. 19

Map of deployments ...................................................... 30

3. Recruitment ................................................................... 31

4. Intrusion ........................................................................ 37

5. Warnings ........................................................................ 41

6. Antecedents ................................................................... 45

7.

Escalation ...................................................................... 54

8. Reports .......................................................................... 69

9. Reconstruction ............................................................... 80

10. Unmasking .................................................................... 104

Organigram ................................................................ 108

11. Integrity ........................................................................ 111

12. Excellency ..................................................................... 132

Part Two

13. Feedback ....................................................................... 136

14. Photo rolls ..................................................................... 142

15. Warning letter ............................................................... 144

16. Book ban ....................................................................... 153

17. Media ............................................................................ 164

18. Court of Appeal.............................................................. 167

19. Appeal judgement .......................................................... 176

20. Press freedom ............................................................... 182

Part Three

21. Parliament .................................................................... 188

22. Rebuttal ........................................................................ 201

Epilogue by Hans Laroes ....................................................... 205

Recommendations ................................................................ 208

Abbreviations ........................................................................ 215

Notes .................................................................................... 216

Illustrations ......................................................................... 252

Synopsis .............................................................................. 256

Synopsis in Bosnian ..................................................... 260

Synopsis in Dutch ....................................................... 264

Synopsis in German ..................................................... 269

Synopsis in Russian ...................................................... 274

Index of persons .................................................................... 279

Introduction

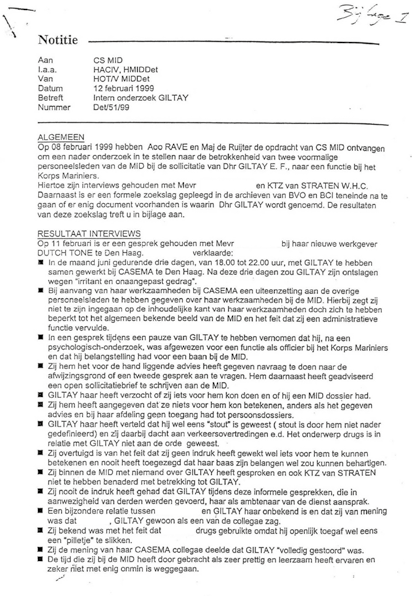

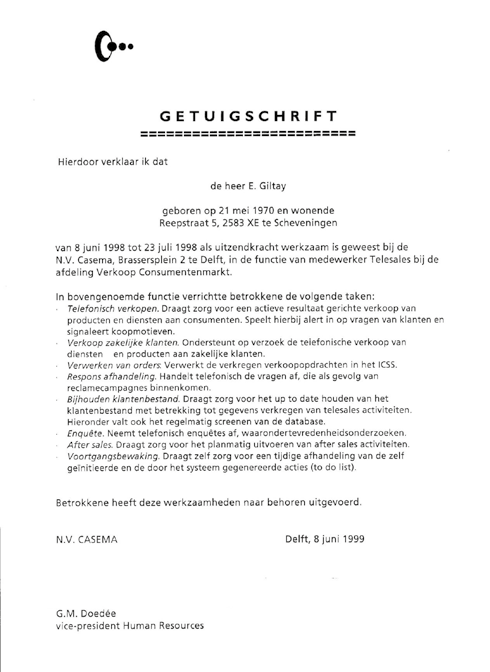

In 1998 I worked at cable television provider Casema in Delft

as a help-desk employee. While employed there I became un-

wittingly involved in government intrigue: a power struggle

within Dutch military intelligence was fought out on the company

floor. The Cover-up General reports on this and follows the ongoing

developments in this unsettling affair.

This spy thriller is an autobiography describing my experi-

ences with secret services. I also explain the background to what

happened to me. In doing so, however, I did not want to make this

affair any bigger or more political than it is. While it is true that

domestic and foreign media repeatedly call The Cover-up General a

‘Srebrenica book,’ this designation gives a somewhat distorted pic-

ture. It describes an affair that takes place in the Dutch lowlands

and focuses only in part on the withholding of an infamous photo-

graphic film of the fall of Srebrenica.

While no details of the actual story are invented, some people

have been given a different name to protect their privacy. For ex-

ample, the names of unsuspecting citizens working at Casema,

who encountered a genuine spies’ battle being fought over their

heads, have been anonymized.

The text has been updated. Following the first Dutch edition,

chapters have been added explaining new developments. In addi-

tion, when the second edition went out of print I rewrote a number

of passages for reasons of improved clarity. In the third Dutch edi-

tion — of which you are now reading the English translation — some

paragraphs on side issues have been deleted and others added. Thus,

I have put to paper what it was like to be targeted by the State of the

Netherlands. Although emptying this goblet of poison was painful

at the time, it is liberating to give it a place now (pages 99–103).

10

The Cover-Up General

As a citizen, it is not easy to defend oneself against a state appa-

ratus. However, support from politicians, journalists and academ-

ics makes it more burdensome to disrupt a citizen’s life without

repercussions. To gather this support the editors of this book

worked diligently. And with success — even before publication, this

book received the blessing of prominent figures.

The reader may not have failed to notice the many endorse-

ments in this book. These are broadly presented here less for

the sake of aggrandizement than out of a consideration for, as it

were, a shielding legitimacy: as the author of a spy exposé, it is —

unfortunately — necessary for me to have a ring of protection.

On page 216 one will find the notes section containing references to correspondence, reports, parliamentary and legal doc-

uments, newspaper articles, etc. In addition, there are two Word

files that form the basis of this book: the first is a document with

painstaking notes prepared when I applied to join the armed forc-

es in 1998. When ultimately confronted with military intelligence

machinations at Casema, I subsequently recorded my observations

in a journal that likewise details the plot twists in this saga.

I did not rush the writing of The Cover-up General. Many friends

and associates assisted in bringing this sensitive affair into the

limelight, in a diligent and responsible manner.

Thus, I thank Dutch journalists Mark Baker and Arnoud van

Soest for their editorial help, as well as news photographer John

Melskens for the author’s portrait taken at the Dutch Ministry of

Defence in The Hague. This international edition of The Cover-up

General would not have seen the light of day without the editorial

help of Irish philosopher Michael Wynne. He has spent many late

nights correcting my English on his laptop — thank you, Mike!

The synopsis of this book can be found on page 257, followed

by synopses in Serbo-Croat-Bosnian, Dutch, German and Russian.

I would like to thank the freelance translators of the summaries

for their conscientious work: Milan Petrović (English to Bosnian),

Mareike Kraatz (English to German) and Yurri Shynkarenko (Eng-

lish to Russian).

In addition, I am grateful to Tom Mikkers, Metje Blaak, Harry

Introduction

11

van Bommel, Jeroen Stam and Christ Klep for their advice. Val-

uable support also came from Bosnia veterans Colonel Charlef

Brantz and Derk Zwaan, Balkan activists Caspar ten Dam, Jolies

Heij, Dzevad Kurić and Jehanne van Woerkom, Srebrenica lawyers

Marco Gerritsen and Simon van der Sluijs, as well as my late Uncle

Frans Erkelens Jr. and his impresario Ian Knoop.

I am also indebted to my lawyer Jurian van Groenendaal. After

this book became the subject of lawsuits in 2015, he prevented it

from being covered up forever.

Related news videos and background articles can be found on

the website thecoverupgeneral.com.

— Edwin Giltay,

The Hague, Netherlands, 2024

12

The Cover-Up General

Part

P One

art

1997 –

199 2

7 – 0

2 14

0

‘Every person remembers some moment in their life where they

witnessed some injustice, big or small, and looked away because the

consequences of intervening seemed too intimidating. But there’s

a limit to the amount of incivility and inequality and

inhumanity that each individual can tolerate.’

— Edward Snowden

CHAPTER ONE |

CHAPTER 1

Character

December 1997, I spot a recruitment advertisement for an

officer’s position in the Dutch Marine Corps, the elite corps

of the Royal Netherlands Navy. Armed marines are depict-

ed, above the slogan, ‘The Navy, not that bad an idea’. The athletic

challenge of this combat unit is appealing. Just like my grandfather

Frans Erkelens, I aspire to serve my country as a military officer.

Several months later, on 3 April 1998, I attend an information

meeting at Amsterdam’s Naval Barracks.1 Lieutenant Commander

Hamaken explains at the barracks what the job entails. He does

not forget to add that a soldier risks giving his life for his coun-

try — a dramatic turn of phrase, yet he chuckles at his own re-

marks. Nevertheless, he emphasises we should keep this in mind

before applying.

The question whether I would be willing to lay down my life for

my country, takes me by surprise. At 27 years old I have not con-

templated this yet. So far, I have been working mainly as a Dutch

technical writer, not a profession in which you put yourself in jeop-

ardy. I take notes during the lecture, something I am used to, so I

can refresh my memory later on.

When Lieutenant Commander Hamaken notices this, he stops

laughing. His tone turns serious and referring to the peacekeeping

operations in the former Yugoslavia, he tells us that in extreme cas-

es a soldier on duty can die.

‘Have you taken all that down accurately, Mister Giltay?’ The of-

ficer addresses me firmly. ‘Yes,’ I reply calmly; ‘I am writing it down

as I consider what you are saying to be important.’ It certainly is,

judging by my grandfather’s experiences. As a prisoner of war, he

was tortured; in vain the Japanese army tried to break him. He had

14

The Cover-Up General

been deployed as a forced labourer in the construction of the Bur-

ma Railway, 2 a war crime claiming the lives of nearly three thou-

sand Dutch soldiers.

Back home, I reflect profoundly on the ultimate consequence

of being sent on a military mission. On the Ministry of Defence’s

website, I read that the armed forces are tasked with defending our

freedom and democracy, as well as advancing the international

rule of law. Justice is not a given, as evidenced by the world war ter-

rors my family had to endure, and which Queen Wilhelmina also

outlined in a personal letter of condolence to Grandpa in 1947.3 The deployment of the Dutch Armed Forces appeals to me. I decide

to apply in order to undertake these duties, whatever the conse-

quences may be.

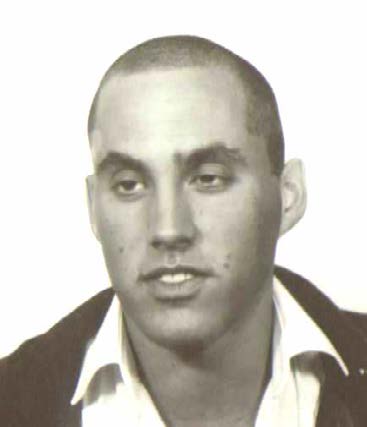

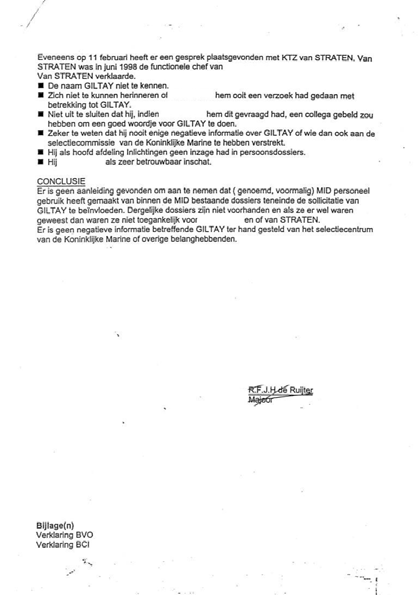

I fill in an application form, which comes

with several attachments. As requested, I en-

close a passport photograph. I also need to

sign up front to swear allegiance to the Queen,

obey the laws and submit myself to military

discipline. And I have not even been admitted

to the ranks. Still, I sign the allegiance, so help

me God Almighty.4

Passport photo

Meanwhile, I have taken up a new temp job.

On 8 June, I will commence at cable operator

Casema, which offers cable tv, telephone and

internet services. 5 As a telephone helpdesk

assistant in the Telesales department, I speak

with potential customers interested in inter-

net access, and arrange appointments in case

technicians are required to make house calls.

The department is located on the fifth floor

of Casema headquarters on the outskirts of the

historic town of Delft. I work from Monday to

Friday, from six to ten pm. The atmosphere is

pleasant, I get along well with everyone, and

the pay allows me to make ends meet. Evening

Chapter One | Character

15

hours pay overtime, so I receive a 30-hour salary for a 20-hour job.

It’s perfect for me — I can work out all afternoon.

On 11 June, I check in at the Amsterdam Navy Barracks for the

psychological assessment of my suitability as an aspiring marine

officer.6 Ms P. Strijbosch explains to me that only information I provide myself will be used. She also guarantees that it will be

treated confidentially. That sounds fair and square, but during the

interview it becomes clear she herself does not adhere to this no-

tion. She raises a few questions indicating that she has knowledge

of my personal antecedents. This is rather surprising, as I have not

yet given permission to be screened by Military Intelligence. Yet

despite my dismay, I keep quiet about it.

Among other things, Strijbosch asks about my current job. I tell

her I started working as a helpdesk assistant in Casema’s internet

department, much to my delight. It strikes me that the military

psychologist is taking notes most decisively, even jotting down

information on the company. To ease tensions, I jest: ‘Would you

perhaps like to come and work at my place?’ Strijbosch smiles and

goes on taking notes.

In the afternoon, I am called in for the results. A colleague of

Strijbosch, Mr P. van der Pol, accompanies me to a room. He comes

right to the point. He thinks I am unfit to become a marine officer

because — and here is the zinger — my character is supposedly ‘too

strong’. Marine Corps drill instructors would be ‘unable to break

me’. He thinks my character is ‘too well developed’ and my broad

work and life experience is commendable.

Not only does the recruitment psychologist put a remarkably

positive spin on me being rejected, but he also surprises me by

bringing up a private matter. Although I did not disclose my sex-

ual orientation, he tells me that while training Marine Corps of-

ficers, the Navy has had bad experiences with ‘guys like me’. The

psychologist explains that in the Marines, homosexuals are not

considered to be one of the boys. As a result, virtually no gay can-

didates reach the end of the training course. Although Van der Pol

knows one gay man who indeed finished the training course, he

16

The Cover-Up General

felt compelled to leave eventually, having been isolated for a year.

Obviously, homosexuality cannot be used as a reason for re-

jecting recruits. However, that does not remove the problem of

gays not being accepted by the Corps. The psychologist lets on he

is not happy with the selection procedure either. He has raised

objections regularly, but his superiors never budged: ‘Nothing

ever changes.’

But how does the director of Recruitment & Selection view this?

Van der Pol replies that the latter barely knows what is going on.

The psychologist does not think highly of the servicemen working

at the naval barracks. ‘Softies’ they are, posted here because they

are unfit to sail.

Being rejected on the grounds that ‘my character is too strong’,

seems a feeble excuse to me. An elite force refusing recruits

deemed too strong for warrant officers to handle, is, I think, simply

ridiculous. As I tell Van der Pol I will be lodging a formal complaint

on the matter, sure enough he appears to appreciate my decision.

Without my asking, he gives me a piece of advice: the military is

wary of negative publicity — such is to be avoided. Therefore, I

should express myself thoughtfully. Van der Pol points out that I

am intelligent yet modest. I do not impose myself and put group

interests first. These specifics go down well with the Corps.

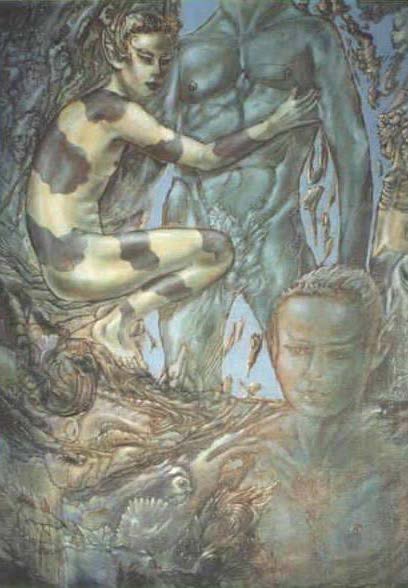

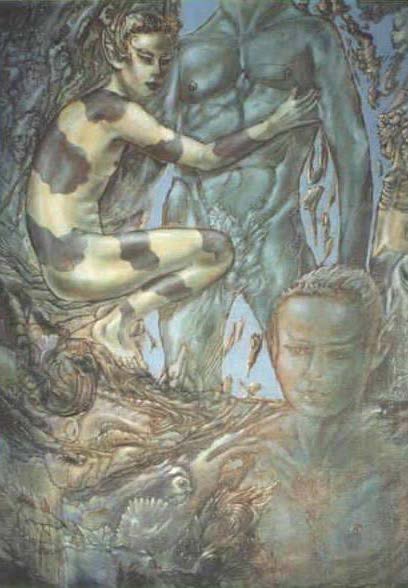

The next day, I visit my maternal Uncle Frans Erkelens Jr. in his stu-

dio in The Hague. Frans is a celebrated painter. 7 Princess Irene, for instance, is an admirer of his, 8 and Queen Mother Juliana opened

an exhibition of his work in Amsterdam’s Nieuwe Kerk (‘New

Church’) in 1981.9 My uncle would immerse himself in a subject for

a while to create a series of paintings about it. Over the years, he

drew inspiration from varied themes such as the Battle of Arnhem,

the Great Pyramid of Giza and its Sphinx, as well as the Javanese

goddess-queen of the South Sea.

Once I explain I was rejected by the Netherlands Marine Corps

on the grounds of my character being too strong to be broken,

Frans starts laughing. In his opinion, I should be happy with the

assessment. Had I not applied to prove my manhood? If anything,

Chapter One | Character

17

is being considered ‘too strong’ not a generous acknowledgement

in this particular area?

In jest, he adds that the Armed Forces apparently realise that

with my tough appearance they are facing too great a challenge.

In essence, I am thought to be no match for ranking officers. His

reasoning: perhaps I have been discussed secretly, by generals

who reckoned they were not in my league. Much to their dismay,

of course.

My uncle’s absurd appraisal of the situation makes me laugh.

Then again, it does not alleviate my disappointment. I regard it my

calling to follow in my grandfather’s footsteps. According to my

family, I resemble him a lot. Yet, as Frans Erkelens Sr. died before I

was born, I only know of him through stories and photographs. Ac-

tually, I know very little about my grandfather. He was a member

of the Dutch East Indies court martial, 10 and climbed to the rank

of colonel,11 though he never did talk about his job all that much.

When I relate that I want to serve my country like Grandpa,

Frans gets serious again. He tells me that as a conscript he received

preferential treatment — having been employed as a writer in Naval

Intelligence, thanks to the reputation of his dad: my grandfather.

My uncle also points out we are descendants of Toontje Poland,

a hero of the colonial Java War. The Dutch vanquished Islamic

warrior-prince Diponegoro in 1830, after luring him into bogus ne-

gotiations. Poland’s ‘acts of excellent bravery’ were rewarded with

the Military Order of William 12 — the highest military honour the

Kingdom can bestow. During the war, two-hundred thousand Mus-

lims were slaughtered.

Jokingly, Frans advises I convey to the Defence Ministry that I

wish to continue a proud family tradition. ‘Maybe then they will

employ you. Although they might then offer you a completely dif-

ferent job.’

18

The Cover-Up General

CHAPTER TWO |

CHAPTER 2

Defence women

Meanwhile, I enjoy working at Casema’s Telesales depart-

ment. The evening workload is light and the office cul-

ture informal. I have young colleagues and as the work is

fairly simple, there is room to chat with each other in between calls.

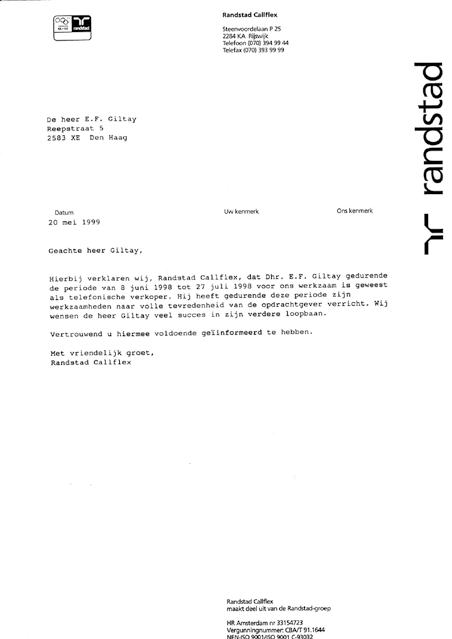

Besides my temp agency Randstad Callflex, there is a second

agency that dispatches flex workers in our department. That com-

petitor is called Teleprofs and is cheaper.

On 3 July, our manager Anna at Casema offers me permanent

employment, as this is cheaper for the company than me working

through the temp agency. I appreciate this kind offer, yet I decline,

as my ambitions do not lie with Casema.

Meanwhile, two new women have joined Telesales, both tem-

porary workers from Teleprofs. My colleague Julia knows of my

interest in the Armed Forces and informs me about the peculiar

background of one of them. She looks me straight in the eye as she

tells me that this flex worker’s name is Monica and this woman is

also employed by the Military Intelligence Service. I cannot believe

my ears. Yet Julia surely pronounces the name of this secret service

very precisely.

The background of our new colleague is surprising. Why would

someone from an intelligence agency come and work for us? My as-

tonishment increases when Julia adds that Monica, who is rostered

during daytime hours, is eager to meet me. She would have already

inquired about me.

Teleprofs’ second new temp is a taciturn woman, estimated to

be nearly fifty. She is to work in our department for five weeks,

Monday through Friday from five to ten pm. When I see her at first,

Chapter Two | Defence Women

19

she tries to ignore me. I introduce myself and hold out my hand,

but to my surprise, she refuses to accept it. When I clarify it would

be nice to know her as we work in the same department, the wom-

an looks unpleasantly surprised by this information. With obvious

reluctance, she eventually shakes my hand and mentions only her

first name: Ina.

She looks like the motherly type. Cautiously, I ask her whether

her husband doesn’t mind her not being home in the evenings. To

that she snarls: ‘He thinks of that in a completely different way.’

Later, when chatting with a colleague at work, Ina tells how she

loves gardening and has a huge garden in Egmond aan den Hoef.

Having never heard of her hometown, I ask her where it is. It turns

out to be a village all the way near Alkmaar. Isn’t it a nuisance hav-

ing to commute to Delft every day for just several hours of work?

With a stutter, Ina says she is staying the nights in The Hague for

her job. Where might that be? At her aunt’s, she stammers.

Ina is not very approachable. For instance, she refuses my help

when she is at odds with her computer. Moreover, to create dis-

tance, she stresses to me her seniority. Out of respect for her sen-

iority, I am more than willing to address her as ‘Mrs’, but since she

won’t say her surname, it becomes difficult to address her in a cor-

rect manner. I try a few times saying ‘Mrs Ina’, but I cease doing so

since everyone simply calls her by her first name.

By the way, there is something odd about that first name. When

Ina is addressed by colleagues on the work floor, it strikes me that

she does not always respond. After this has happened a few times,

I ask her if Ina is indeed her real name. She is startled by my ques-

tion. She answers ‘Yes’, while stuttering violently.

Later, my colleague Angela asks me if it is true that I applied for

a job in the Navy. When I confirm this, she tells me that she heard

from Ina that her husband also works there. Both new temps there-

fore turn out to be Defence women, which is remarkable.

Once I have a moment alone with Ina, I ask her what her hus-

band does for a living. After all, I am curious about her mysterious

background. I may have put my question to Ina somewhat out of

the ordinary, by the way. Maybe it is my intuition. Or is it clumsy

20

The Cover-Up General

once I ask her what her husband does ‘at the MoD in The Hague’?

She is shocked by my words. Instead of replying, she asks with

an apprehensive look how I figured out her husband’s profession.

That is a surprising response because it confirms that her husband

works at the Ministry of Defence (MoD) in The Hague, where main-

ly senior staff officers are based. Hereupon I decide to increase the

tension a little by remarking dryly that I have connections.

I have to laugh a little at Ina’s reaction, but soon I notice that she

is shocked more than I had anticipated. I then try to calm her down

by explaining that she herself had revealed her husband’s occupa-

tion to Angela. Still, I fail to calm her down: she is too horrified.

On another evening, Ina is talking to Angela about the opening

phrase she uses on the phone. I hear Ina state vigorously that she

only uses her maiden name at Casema.

Her uptight conduct never ceases to amaze me. I cannot hold

back and ask her why she does not use the name of her military

husband. Ina is startled once more by my directness and declines

to answer. She forbids me from mentioning her husband’s profes-

sion; I am supposed to keep her military relationship a secret.

When we pick up the phone at Telesales, we always mention

Casema’s name first and then our own. When I hear Ina answer the

phone at a certain point, however, she makes a mistake. She seems

to have daydreamed, forgetting for a moment that she is in a busi-

ness environment. She only mentions her name. To my surprise,

she doesn’t say ‘Ina’, nor does she use her maiden name. Instead,

sweetly she introduces herself as ‘Mrs Van Baal’.

She is hugely embarrassed that she has divulged her identity.

‘Oh, how silly of me!’ she says aloud. She then apologises through

her headset to her unsuspecting internet customer. Ina actually ex-

cuses herself so profusely for her slip of the tongue that it almost

seems as if she has committed a true mortal sin by revealing her

real name and thus her husband’s surname.

‘Mrs Van Baal’ does not notice me observing her and laughs for

a moment at her own stupidity. Then she tries to recover. In an

exalted tone of voice, she mentions the name Ina. For the sake of

completeness, she adds that she works at Casema, before finally

Chapter Two | Defence Women

21

listening to her internet customer on the other end of the line.

Her slip of the tongue makes me realise that strange things take

place on this work floor. My intuition tells me I should remem-

ber the name Van Baal well. Although I try to focus on my work,

Ina draws more and more attention to herself with her peculiar

behaviour.

Yet things are about to turn even stranger. When I turn up at

the office on Wednesday 8 July — the day before I was called off due

to overstaffing — supervisor Marlies strikes up a conversation. She

is the informal supervisor of Telesales in Anna’s absence, and she

says she is worried about what happened the previous day.

To make copies in the hallway, she had left her staff badge at her

workplace. However, on returning with the printouts, her badge

was gone.

Marlies is stunned. Hardly able to believe it, she suspects Ina

stole it. After all, Angela and Ina were the only two who had re-

mained in the department. Angela could not have been the one

because she has known her for so long. And so, the suspicion nat-

urally falls on Ina.

A staff pass is issued at Casema only to regular employees.

Temporary workers like Ina and me can therefore only enter or

leave the secure premises when accompanied by a colleague with

a badge.

Marlies says that her stolen card contained a consumption

credit of just pennies for the snack machine in the hallway. How-

ever, she cannot imagine Ina stole her badge simply to relish a free

snack. You wouldn’t expect that from a middle-aged woman, right?

Apart from Ina, I also get to know our new temp Monica. She greets

me warmly when I appear at the department at a quarter to six.

Monica is an attractive blonde woman. She bears a striking re-

semblance to Czech tennis star Martina Navrátilová. Monica wears

dark-brown leather trousers, lending her a butch look. Even though

she had already finished work at five o’clock in the afternoon, she

continued for an hour longer on her own initiative. This in order to

meet me, as she lets me know right away.

22

The Cover-Up General

I do find it amusing that Monica, busily moving her hands while

talking, shows such interest in me. Julia had not been kidding then,

when she mentioned that Monica was eager to meet me. I react

joyfully. Monica’s initiative is in sharp contrast to the way Ina tries

to ignore me.

Monica says she has already heard a lot about me and works at

the ‘M… I… D… ’. ‘She pauses briefly after each letter as if giving up

a riddle. I ask Monica whether she likes working at the Military In-

telligence Service (Dutch: mid), to which she expresses her appre-

ciation for the fact that I know what those three letters stand for.

Immediately, she starts complaining about the workload and

stress at the mid. To my surprise, she is in no way reluctant to criti-

cise her employer openly. Also, she tells me that there is a lot going

on at the mid about an infamous ‘photo roll of Srebrenica’, a sub-

ject about which I only vaguely remember hearing something in

the media.

Monica explains that her boss has given her an entire week’s

leave from her full-time job at the mid, in order to work at Casema

during the daytime. As I then point out that I only work in the eve-

nings, she nods affirmatively and says she has already adjusted her

hours. From next week, she will be in the office from six to ten pm;

that will give us the same working hours.

When I got to meet Ina, I surprised her when I mentioned that

we happened to work in the same department. Monica is equally

surprised. She wants to hear from me why I am not working at the

neighbouring Internet Helpdesk.

Reflecting on this, I think back to the interview at the Amster-

dam Naval Barracks. When I answered that I was a helpdesk assis-

tant — my job title according to Randstad Callflex — this was written

down remarkably accurately. Could this be the reason for the con-

fusion of the two Armed Forces women? Might the professed con-

fidentiality of the psychological interview have been breached? I

find this hard to believe, but do not rule it out.

When I ask Monica why she believes I work at the Internet

Helpdesk, she replies that she finds that more fitting for me. We

met just a few minutes ago — I remark that she certainly assesses

Chapter Two | Defence Women

23

me very quickly. To this, Monica says with a broad smile that she

has had a good impression of me for quite some time.

On another evening, I see Monica again at Casema as she is about

to go home. Again, she complains in her rather loud voice about

the Military Intelligence Service and the photographic film of the

Srebrenica tragedy. This time it strikes me that a colleague who’s

sitting behind Monica is listening in attentively. It’s Ina, the oth-

er Defence woman. Looking past Monica, I see Ina’s jaw drop in

amazement at everything she is saying. Monica doesn’t notice this

and tells me that I really shouldn’t believe that the photo roll failed

to develop. It is just stored in the archives of the mid. She also

says, ‘You can understand yourself why the photos have not been

released.’

I barely know what she is talking about, but find it exciting that

someone from an intelligence agency is informing us of real state

secrets. I tell Monica I don’t know. She then reveals in the presence

of colleagues that the photos are damaging to the military.

Later that evening, Angela asks Ina what again is Monica’s re-

markable profession. Ina appears to have forgotten that, although

she listened open-mouthed when Monica talked about the mid. In

a weak voice, she remarks: ‘Ah yes, what was that again?’

In a quasi-accusatory tone, I shout: ‘She’s a spy!’ It’s just a gag,

but Ina flinches violently. When I then look her straight in the eye,

for a moment it appears she feels like she’s been exposed. This sur-

prises me since I was merely joking about Monica’s ‘infiltration’

into our firm, not Ina’s.

I find it hard to believe. Why would military spies infiltrate an

office department in Holland where subscriptions for cable inter-

net are sold?

The jittery way Ina reacts makes me curious about what she is

up to. At some point, I get the inkling to ‘sneak up’ on Ina. I decide

to do this when I need to hand her a sign-up sheet anyway.

While Ina is sitting at her desk, I first walk to the window behind

her with the form and a cup of tea. Ina turns around suspiciously.

However, when she sees that I am just staring out the window, she

24

The Cover-Up General

is once again put at ease. She continues what she is doing. Half a

minute later, I leave the tea on the windowsill and tiptoe over to

Ina. I breathe softly. Cautiously, I look over her right shoulder.

To my utter amazement, I see Ina taking notes on her Telesales

colleagues. In a lined school notebook, she has written down her

observations after each name. The notes are elaborate: on each col-

league she filled one to several paragraphs. Her rounded handwrit-

ing is easy to read. Moreover, the structure of the notes makes it

easy to comprehend them quickly. Ina uses pens with two colours.

Some words she has underlined with a ruler.

First, my eye catches what she wrote down after my underlined

name: she complains about my impertinent questions. One can

read also that Monica laments about the Srebrenica photo roll.

As Ina flips back a page of her notebook, I stumble upon a writ-

ten confession. Hastily, I read that Ina stole Marlies’ access card

while making copies in the hallway.

I am dumbfounded. What this is all about is beyond me.

I cannot read along for long as Ina suddenly senses that I am

standing behind her. She rocks violently and bounces up from her

chair. Quickly she hides her notebook beneath the other papers on

her desk. I ask her if she has a secret to hide, but she does not an-

swer. Her face turns red.

I still wish to give Ina the registration form, but she’s unwilling

to take it. Even when I add that it is a form from one of her clients,

she refuses to accept it. Ina seems utterly confused. With a sigh, I

put it down on her desk in the hope that she will later realise what

Casema hired her for — to enrol internet customers.

Ina’s confusion gives way to anger. Again, she issues a ban. Be-

sides my being required to keep her military relationship secret,

I am now no longer allowed to walk towards her without her first

seeing me approach her. Apparently, I am to give her space secretly

to describe everyone in her little notebook.

On 13 July, I take a day off. The next evening, I sit together with

Monica and Ina at one joint desk. In between phone calls from cus-

tomers, Monica complains that many things happen at the Military

Chapter Two | Defence Women

25

Intelligence Service that are completely irregular. No one at the mid trusts anyone anymore.

As Monica is grumbling about the mid, she seems unaware that

there is another Defence woman in the group. Actually, she tells

her colleagues that she feels at ease with us. And that it is a relief

for her that she can finally be herself amongst us after her daytime

work at intelligence. For instance, she takes the liberty of calling

her girlfriend and flattering her with sweet words.

She feels so at ease that she proposes to talk about first love ex-

periences. From female colleagues, she likes to know what their

‘first time’ was like. Ina feels uncomfortable with this intimate sub-

ject; her body language indicates that she does not want to expose

herself. For a moment, I consider helping Ina out. However, as Ina

sometimes snarls at me, I don’t interfere.

Despite her obvious reservations, Ina recounts her love story.

In doing so, she soon ends up with her husband, whom she lov-

ingly calls ‘my Ad’ thereby casually disclosing the first name of her

military spouse — something she does not seem to realise. On the

contrary, she breathes a sigh of relief that having recounted meet-

ing Ad, she is done answering Monica’s question.

Monica, who talks enthusiastically about the girlfriends she

used to sneak kisses with in her school’s bike shed, does not ask

about my first intimate experience. Rather, she talks to me about

other topics. One evening, for instance, she tells of two befriend-

ed MoD colleagues who started talking to the press. In the radio

programme Argos, they anonymously criticised the mid’s handling

of the photographic film of the fall of Srebrenica. At the mid, says

Monica to me, there was a lot of buzz today about these embarrass-

ing revelations. According to her, Military Intelligence would not

know how to deal with the truth.

It disappoints Monica that I don’t know Argos. She explains that

this current affairs programme is broadcast by vpro on Radio 1.

In addition, she says that with my background, I should take more

interest in the upheaval over the photo roll. This remark makes me

suspect that she sees in me a sounding board for her secret service

work. I let her know that, like her, I am an advocate of openness.

26

The Cover-Up General

Without my asking, Monica explains why the photo roll is be-

ing withheld. According to her, the reason is rather trivial, but in

the Armed Forces, some would definitely want to prevent the pho-

tos from being published. There is fear of publication in a popular

opinion magazine like Panorama or Nieuwe Revu.

And then Monica tells me she attended a secret MoD meeting

on the photo roll. There, someone had insisted that the Dutch sol-

diers involved in the fall of Srebrenica should be protected from

publication. It was necessary to prevent the boys in the photos

from being recognised by their relatives and friends. It would be

unpleasant for them should the photos be published in the tabloid

press. At the tennis club or at the pub they might be confronted

with their role in the Srebrenica tragedy.

I ask who brought this up, but Monica is not allowed to say. She

only wants to reveal that it concerns a man who was invited to this

intelligence meeting even though he did not belong to the mid.

Monica’s comments regarding the upheaval arouse my curiosity.

Apparently, it has been arranged with the mid that the Dutch gov-

ernment could be deceived about the photo roll.

Later, I follow Monica’s advice and research the fall of Srebren-

ica and the infamous photo roll. Thus, I learn that during the Bos-

nian war, the United Nations (un) had designated the town as an

enclave for Bosnian Muslims, called Bosniaks. Dutchbat, a Dutch

un army battalion, had to protect the enclave. Nevertheless, the

town was captured by Bosnian Serb forces on 11 July 1995. The

Dutch offered hardly any resistance to the advancing Serbs.

After the takeover, the Serbs killed more than eight thousand

Bosniak men and boys. Officers responsible for their protection in

the enclave included the Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Neth-

erlands Army, General Hans Couzy, and his deputy General Ad

van Baal.

I ask the vpro for a copy of the Argos broadcast of Friday 10 July

1998, which deals with the withheld photographic film of lieuten-

ant Ron Rutten. The programme features General Couzy; Van Baal

does not get to speak.

Argos’ editors explain that the photo roll contains pictures of

Chapter Two | Defence Women

27

murdered Bosniak men, pictures that could serve as evidence for

the war crimes committed by Bosnian Serb servicemen in Srebren-

ica. But let Argos speak for itself:

The photos were taken two days after the fall of the enclave by

three Dutch un officers: two lieutenants and one adjutant. They

had gone to investigate near a stream and found nine corpses

there. Lieutenant Eelco Koster was one of the three: ‘I got my-

self to stand among these to demonstrate and say: listen, the un

has been here and we have proof of people being killed here.

And with this evidence, we thus want to show the world what

happened in the enclave in these days.’

The three even risked their lives, Koster told tv programme

Nova last April [April 1997]. Because immediately after they had

taken the photos, they were discovered and shot at by Serbian

soldiers. Still, they did manage to escape to the Dutch base and

bring the roll to safety. Once back in the Netherlands in late

July [1995], the roll was ruined while being developed in a Navy

photo lab.

The cover-up of this photographic film for which Dutch officers

risked their lives, raises questions: how does the misappropriation

of such evidence of war crimes relate to the Armed Forces’ duty to

promote the international rule of law? The roll proves that prior to

the genocide, Dutchbat was aware that the Serbs were killing Bos-

niaks in Srebrenica. Does the Dutch army perhaps prefer not to be

confronted with this reality?

Argos offers an explanation as to why the mid covered up the

photos. The radio programme says it spoke to a senior serviceman

closely involved in the Srebrenica operation. To ensure his ano-

nymity, the interview with him had been re-enacted.

In the recreated interview, the senior serviceman reveals that

there were also other photos on the roll:

Look, there are a lot of stories that have not been told. … [about]

things one shouldn’t have done, that are not in one’s mandate.

28

The Cover-Up General

For example, that one thus helped the Serbs to bring displaced

persons [the Bosniaks] to the bus or out of the compound [the

Dutchbat barracks in the Srebrenica enclave]. Look, you can

say: so at least then I am certain that these people are not beaten

and robbed or whatever. But the reverse is also true, of course,

because you can also say: listen guys, we are not participating

in this. And what those Serbs do, that’s their own responsibility.

On Casema’s work floor, Monica explains that fear of publication

is actually the only reason why the photos are being withheld. Ac-

cording to her, other issues would not play a role.

Monica sighs that she wants to leave the mid because it makes

her ‘totally crazy’. For the first time in all her years working at the

mid, she took this side job. Although civil servants are not allowed

to have a second job, Monica says she and her girlfriend can make

good use of the extra income. After all, she has no savings because

she spends a lot on parties and buying leather trousers.

She also tells of her own accord how she ended up at Casema.

She seems to be trying to convince her new colleagues that she

joined us in a normal way, as if it were not unusual for someone in

the intelligence sector openly to hold a second job.

Monica reveals that she was shopping in the street Noordeinde

in the city centre of The Hague. To her surprise, she saw a vacancy

announced at the employment agency Teleprofs already outside.

She decided to apply immediately. Perhaps Monica had taken

her cv with her when she went shopping that day, because she was

able to join us right away.

Apparently, this Teleprofs branch in The Hague believes it is

tasked with giving jobs in Dutch businesses to intelligence officers.

During MoD working hours, mind you. Defence woman Ina, who

lives in the North Holland countryside, is employed through the

same agency. The travel distance between her home in Egmond

aan den Hoef and Delft is almost 100 kilometres (60 miles) while

Teleprofs does not reimburse travel expenses. It doesn’t seem to

bother Ina. On the contrary, I see her beaming when she remarks

that, just like Monica, she has also managed to start working for us.

Chapter Two | Defence Women

29

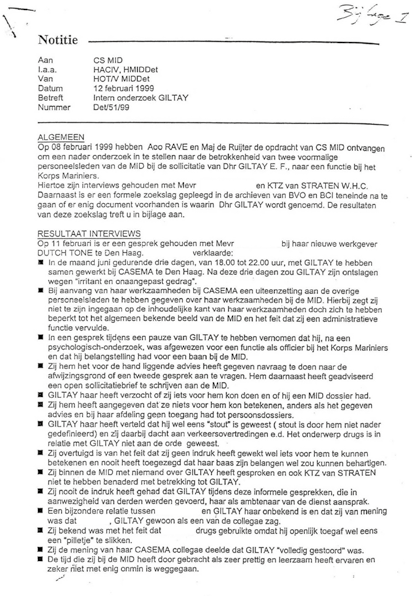

Alkmaar

• Egmond aan den Hoef

North Sea

Amsterdam

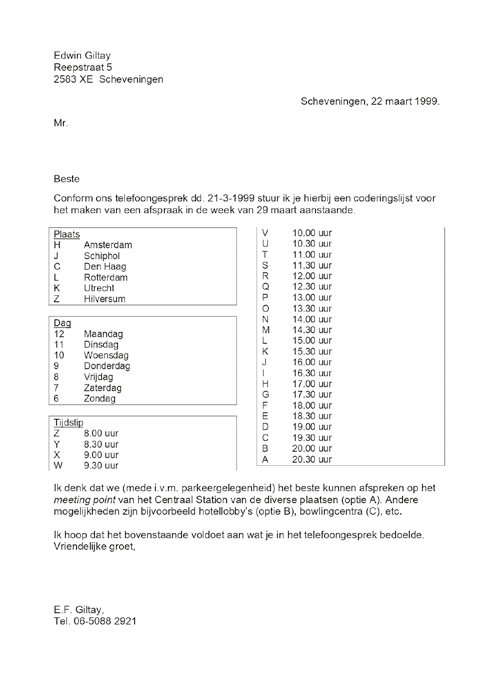

Ina of Egmond aan den Hoef reports to

Teleprofs in The Hague and gets a part-time

job at Casema in Delft 100 kilometres from

home. For her job, she stays in The Hague.

MID

•

Monica works full-time

Teleprofs • The Hague

for the MID in The Hague and

gets time off to work as well for

Teleprofs at Casema in Delft.

• Casema

Delft

Map of deployments

The pride with which the two Defence women talk about their

‘deployment’ to Delft tickles my funny bone. But when I welcome

my new colleagues enthusiastically, this is not appreciated. My

joke that there is certainly room for more ‘spies’ at Telesales is not

understood. Monica and Ina are thrilled by their missions and I

should not ridicule them. Their deployment is a serious matter.

30

The Cover-Up General

CHAPTER THREE |

CHAPTER 3

Recruitment

Encouraged by Monica’s candour, at Telesales I start talking

about my Navy application. Monica responds immediately

— she invites me to talk about it further in the pantry of our

office floor during our break.

Face to face, Monica talks endlessly about her job at the MoD.

The break runs late and she asks me to bring my application papers

the following day.

That next evening, we again take a break at eight o’clock. When

Monica and I get up to go to the pantry, I invite Ina to join us and

drink coffee together. She declines the offer, however, preferring to

stay at her desk.

During the two interviews, Monica explains that she has worked

in the Military Intelligence Service for more than seven years. She

holds an important position and her immediate superior is a Ma-

rine Corps Colonel. To clarify that this is a high rank, she needless-

ly explains that this position in the military hierarchy is directly

below that of general. She does have a new boss now, but basically

still works for her colonel. She has been close friends with him for

years, unlike her new boss with whom she does not get along.

Next, Monica indicates that her intelligence service needs en-

thusiastic people like me to balance out her ‘flawed’ colleagues.

According to her, my sparkling personality would have a positive

effect on the atmosphere at the mid. To emphasise her arguments,

Monica refers to our brief conversations about the Srebrenica pho-

to roll. Hadn’t I told her to be an advocate of openness? Well then!

As far as she is concerned, I have the right mindset to join the mid.

I cannot suppress a smile as I have to get used to her praise.

However, my talkative colleague does not leave any room for my

Chapter Three | Recruitment

31

doubts. Monica believes in me, that’s clear. When she inquires

about my work experience, I barely have time to talk about my ca-

reer before she interrupts me. Without having told her much, she

concludes that — like her — I am way too advanced for the simple

work at Casema. She points to my broad work and life experience.

I have to laugh at her flattering words. When I applied for ma-

rine officer, this was also pointed out. Where at the time it was an

excuse for rejection, now it suddenly makes me fit for an intelli-

gence job. All a bit confusing.

Monica is unstoppable. She praises my analytical and writing

skills, as well as my command of English (as a Dutch speaker). Add

to that my interest in international politics and diplomacy, and you

have an assortment of qualities which the mid can put to good use.

According to Monica, I am ideally suited to produce intelligence

reports for the deployment of military personnel.

She cites the peacekeeping operations in the former Yugoslavia

as an example. For such operations, Personnel of the Armed Forc-

es who are to be deployed have to be informed about the situation

they will encounter before their departure. Mapping conflict par-

ties, describing the local security situation: Monica is convinced I

would be good at such tasks.

Monica cannot stop talking about the need for information on

the warring factions, only to complain about the atmosphere at the

mid, which has been ruined by intrigue. Almost everyone is leav-

ing the mid; numerous vacancies cannot be filled. So, analysts are

in high demand, a position for which she considers me suitable.

Monica keeps talking and before I know it, she urges me to write

a cover letter to the mid. The request overwhelms me. How do I go

about this? Can I use her name in the letter? Yes, I can. Monica —

articulating her full name carefully — instructs me to write that,

as an employee of the mid during her temp job in the corporate

sector, she pointed out to me the many vacancies at the mid. The

letter must be addressed to the MoD in The Hague.

Monica promises me that she will arrange with her colonel for

me to work as an analyst at the mid. It pleases her that I have no

holiday plans or other commitments this summer. She expresses

32

The Cover-Up General

the hope of welcoming me as an mid colleague in the near future.

In the letter, I need to beef up my work experience and skills

considerably. Above all, don’t be so humble, Monica adds in her

loud voice. Hence, she instructs me to mention that I have writ-

ten theses on every conceivable topic I happen to be interested in.

The mid doesn’t check everything after all. When she came to work

there, she didn’t know that; but over the years she has experienced

it to be so.

I am surprised that Monica has no problem with the truth being

violated. Whether the chances of exposure are high or not does not

matter. It troubles me that Monica thinks so lightly about falsifying

facts, as if this were normal in intelligence circles.

Monica fails in recruiting me for her secret service because I

have no desire to work in a toxic place. The trap of mistrust and

deceit that Monica keeps bringing up when she talks about the mid

does not attract me at all. Besides, I have other ambitions than sit-

ting in an office making analyses all day. I am not a nerd. I feel good

about myself and I am more attracted to physical occupations: I am

up for a physical, military challenge.

When I tell Monica I was rejected by the Navy because my char-

acter was deemed too strong to be broken by the drill sergeants,

she responds with immediate disdain. ‘Ridiculous!’ she exclaims.

She is convinced there are other reasons behind it.

For a moment, I consider informing her about the gay discrimi-

nation in the Marine Corps. But I don’t feel compelled to lament in

the company pantry that the military presumes I am gay. Although

the tough vibe of a position in the Corps appeals to me, my sexual

orientation plays no role in this career ambition. Putting my love

life on the table? Such a private matter should be far from a topic of

conversation of this kind.

Monica asks if I have ever been ‘naughty’. I don’t quite under-

stand what she means by that, but she wants to know if I’ve been in

prison or addicted to heroin, for example. ‘No,’ is the answer. I have

never been in trouble with the police or judiciary. I don’t smoke,

rarely drink and don’t use drugs. Unlike Monica, who lights up cig-

arette after cigarette, I don’t have anything to do with addictions.

Chapter Three | Recruitment

33

However, an incident from years ago does come to mind. Police

detectives then asked questions about a crime I had nothing to do

with. Just as I am talking about it, a colleague from the Internet

Helpdesk walks into the pantry to get something. His expression

shows his surprise at our topic of conversation and makes one

realise that it is inappropriate in business to inquire about such

matters. Promptly, Monica suggests that she herself carry out a

background check on me.

I consent to that. At the interview at the naval barracks, I was

already surprised by suggestive questions indicating that the in-

telligence community had passed on information about me to the

selection-psychologists. That violates the Wet Veiligheidsonderzoeken

(‘Security Investigations Act’) and the professional code for psycholo-

gists. I hope the Military Intelligence Service can now clarify this.

‘Can you accurately write down your official name, first names,

date and place of birth?’ Monica says she needs the exact per-

sonal details to check my antecedents — so I must not make a

spelling mistake.

The MoD asked for precisely the same data before. I had to fill

them in on an appendix to the application form because they were

needed for an ‘unspecified official administrative purpose’ as the

Navy cryptically called it. And, I also needed to have that attach-

ment checked at City Hall — for ‘legalisation’.

I now understand what the exact personal details were needed

for: the security screening, which, by the way, was not allowed by

law just yet.

First, the vetting process had to be completed. Then I had to

give written approval to the Head of the mid, General Jo Vande-

weijer, before the secret service was allowed to screen me. For that

matter, the Royal Navy would not be given access to the anteced-

ents. Upon completion of the security screening, the mid would

only pass on whether the ‘Statement of No Objection’ had been is-

sued, Navy spokesman Hamaken explained a few months earlier.

Suddenly, we are disturbed. It is Wednesday evening, July 15 — the

digital clock on the kitchen counter reads 8.08 pm — when I hear

34

The Cover-Up General

a clang. The pantry door is rudely slammed shut. A few seconds

later, we are startled again. Bright flashes of light reflect on the

windows.

I straighten my back and look around to find out who is photo-

graphing us. To my left is a large window. Are the flashbulbs per-

haps coming from outside? This seems odd as the flashes are bright

and we are not at street level, but on the fifth floor. On the right is

the slammed door to the corridor, with a small window next to it. I

do not, however, see a photographer.

Amazed, I remark: ‘It looks like we are being photographed.’

But Monica is so absorbed in her recruitment task that she man-

ages not to be distracted. At the dining table, I write the requested

personal details on a copy of a letter I wrote to the MoD inquiring

what is the matter with my naval job application. 13 While reading it aloud, Monica’s mind seems to wander as soon as I utter the name

of my grandfather, whom I want to emulate. I ask her if she per-

haps knows my uncle. After all, he bears the same name and enjoys

some fame in The Hague as a painter.

Monica does not respond to this and takes the letter. She prom-

ises to collect my personal file from the mid next week.

She thinks I should not be so naive and adapt to what is custom-

ary within the military. That my application to the Marine Corps

turned out so odd, wouldn’t say much about marines. Then she

talks about her boss at the mid. Her Marine colonel — whose name

she is not allowed to mention — has been in constant conflict with

mid top brass in the past. He is one of the few who has the guts

repeatedly to criticise the leadership.

Monica goes on to say that her Marine colonel knows about my

application to the Corps. My jaw drops when she tells me that the

man is doing his best for me to join the Armed Forces.

It is strange that Monica has been given a week off to work in

our department. The thought that she has been sent out to recruit

me for an intelligence job is bizarre. That’s quite a cumbersome

recruitment method! Other employers who want to offer you a job

will send you a letter. Or they call.

Despite my reservations, I refrain from commenting to Monica.

Chapter Three | Recruitment

35

I have insufficient understanding of the spy profession and am flat-

tered by the attention she gives me. And that a colonel of the Ma-

rines is committed to me, I am eager to believe.

36

The Cover-Up General

CHAPTER FOUR |

CHAPTER 4

Intrusion

After our conversation, Monica and I return to the depart-

ment. Ina has isolated herself and is the sole person sit-

ting at a separate desk island. Around half past nine in the

evening, Ina excuses herself as she needs to make a private phone

call. This is unnecessary since other colleagues habitually make

brief calls home. However, I have not heard Ina make a personal

call before; curiously, I listen in.

Although she conducts her conversation in a loud voice, she has

to repeat some sentences. Does she have a bad mobile connection?

Nervously, she reports that everything is going well and then an-

nounces in a cracked voice that the video-recorder can be started.

Which tv programme she absolutely does not want to miss, she

does not say.

Once finished, she takes off her headset. She stands up and ex-

cuses herself a second time, as she needs to go to the toilet. This is

rather ludicrous, considering no one bothers with such unneces-

sary courtesies. Monica responds laconically: ‘Yes, if you have to

then you have to.’

Ina leaves three colleagues in the department. Monica and An-

gela sit opposite me facing the corridor. And then: light flashes

again. Amazed, Angela notes that an unknown man is photograph-

ing us from the hallway. I turn my office swivel chair around but

see an empty corridor. He appears to have already disappeared.

Monica, who, like Angela, did see him, is terribly shocked. She

turns white and trembles visibly when I ask her if she knows who

the man is. ‘No, I don’t know,’ Monica says, stuttering.

The next moment, Ina returns. In an extremely tense and

wooden manner, she walks to her desk. Asked by Angela about

Chapter Four | Intrusion

37

the photographer she denies with the utmost vigour that she saw

anything at all. For that, Ina says she was at the lavatory for quite a

while. Next, she lashes out at Angela. She snarls that she does not

accept ‘being harassed with such impertinent questions.’ Angela is

shaken by these words and humbly apologises.

Meanwhile, worried colleagues from the Internet Helpdesk

come rushing into our department: do we perhaps know who the

photographer is? None of us claims to know him.

Suddenly Monica wanders off. I consider going after her to calm

her down. However, I cannot leave — through my headset I am talk-

ing to a client. This woman doesn’t like the fact that I just asked a

colleague a question and demands my attention.

When Monica returns after a few minutes, she has tears in her

eyes. She tidies up her things and leaves early without addressing

anyone. She remains absent for the rest of the week.

The next evening, Nathan, an Internet

Helpdesk colleague, tells us that the

photo incident has been reported to the

Delft police. He believes we are dealing

with a case of corporate espionage.

The stranger, Nathan reveals, en-

tered the headquarters without setting

Casema office

off the alarm. He then walked past

Telesales and across the floor of the In-

ternet Helpdesk with an impressively

large camera. Here, he dazzled helpdesk

colleagues with his flashes.

A colleague of Nathan’s had the pres-

ence of mind to go after the photogra-

pher and get into the elevator with him.

He had also asked the stranger what he

was doing. The intruder sufficed with a

short answer: ‘This just had to be done.’

Nathan says the photographer once

again managed to bypass the alarm on

38

The Cover-Up General

leaving the premises. He therefore wonders how the man got a

staff pass.

An accomplice waited for him in a car outside. The Casema

colleague pursuing the photographer read the registration num-

ber before the car sped away. Finally, colleagues from the Internet

Helpdesk saw the getaway car from the fifth floor turn onto the A13

highway, in the direction of The Hague.

The police had already tried to trace the Dutch car registration

number, but it does not appear to be registered anywhere. We all

find this strange. Apparently, we are not dealing with ordinary bur-

glars here.

Nathan has no idea what the photographing spy was looking

for on our office floor. After all, there are no confidential company

documents on the fifth floor. Also, he wants to know who the wom-

an is that he saw coming from the toilet. He did not yet know Ina

and found her attitude suspicious when he spoke to her, especially

as she was signalling to the photographer the second she left the

toilet. Nathan therefore suspects her of involvement in the indus-

trial espionage.

Lisa, the boss of our manager Anna, also wants to speak to me.

She takes the time to talk to all employees who were present during

the incident. Lisa confirms that the police have been called in be-

cause of the espionage. The Casema management is worried.

Face to face, Lisa explains that the intruder wanted to photo-

graph Monica. She finds it incredibly strange that this mid officer

has started working with us and that she talks openly about her

intelligence work. But she doesn’t trust Ina either.

Lisa heard from a colleague that I applied to the Marine Corps.

I tell her I was turned down as my character was said to be too

strong to be broken. She doesn’t understand that, to which I reply

that I don’t understand it either and that I spoke to Monica about it

during the break. She works at the Ministry of Defence (MoD), after

all. Lisa nods understandingly and sighs as she searches in vain for

clues to explain the break-in.

Later, another colleague also starts a conversation with me.

Mark, a thoughtful Surinamese, is new to Telesales. He says he is

Chapter Four | Intrusion

39

worried. He was not scheduled on the evening of the intrusion and

asks what happened. I relate, but also ask him some questions.

Walking to the tram stop with Julia after work, I ask her opinion

regarding Monica’s moaning about the photo roll. Although Julia

was the first to divulge Monica’s double life, she now no longer

dares to talk about it. She says it is a dangerous subject.

By now, the events are starting to worry me too: simply because it

is so bizarre that Monica has been sent to us, I have joked at times

about spies. But those were harmless gags. Real espionage is a sub-

ject far beyond my normal experience.

I do not realise exactly all that I have witnessed. Take the note-

book that Ina was writing in. Although I cursorily read in it how she

stole a badge, this memory has since faded. All the bizarre events

are piling up too fast for comfort.

When Ina noticed me standing behind her, she hurriedly put

away her notebook and turned red. While I realise she felt she had

been caught, I don’t attach too much importance to it. She can bare-

ly use a computer; she struggles to find her feet in the department.

Therefore, it seems endearing to me that she secretly keeps a kind

of diary in which she writes down her experiences in her new job.

It has not yet dawned on me that with my glance at Ina’s note-

book, not only is a Defence woman revealing her true role, she

is exposing potentially the Defence organisation itself. Although

Monica complains that the MoD is resisting openness about Sre-

brenica, it does not enter my mind to suspect Ina of playing a role

in this. When you think of a spy, you think of James Bond and not a

mummy who is fond of gardening. Should I have accused her of in-

filtration and military observation? And that in the Telesales depart-

ment of Casema? Who comes up with something that ridiculous?

Even more than the espionage break-in, my application pro-

cess is occupying my thoughts. First, I am turned down because

my character is allegedly unbreakable, then I am offered a job in a

secret service, and now my antecedents are being exposed as there

might be something wrong with them. It feels ominous.

40

The Cover-Up General

CHAPTER FIVE |

CHAPTER 5

Warnings

On Friday evening, 17 July, I strike up a conversation with

Ina when I am briefly alone with her in the department. I

tell her I suspect the Navy rejected me because of a gay af-

fair. Quite to my surprise, Ina responds with empathy. Lovingly, she

talks about her relationship: she confirms that she knows from her

husband that homosexuality is indeed a very sensitive subject there.

But then she is startled. Apparently, she realises she has again

disclosed that her husband works in the military. She clams up

again. Still, I tell her that I have talked to Monica a lot about the

mid and that she is going to look into my personal dossier.

Ina starts trembling. While I previously encountered a sore

point when I linked her husband to the MoD in The Hague, this

time she gets rather tense as soon as her husband surfaces in a

conversation about the mid.

I feel pity when I see Ina, who could have been my mother given

her age, trembling with fear. ‘There will be trouble over this,’ she

stammers, referring to Monica’s plan to check my antecedents. I

decide to leave the subject that is driving her to despair, and con-

centrate further on work.

Monday, 20 July, I am called off by Casema and drop by Uncle

Frans’ painting studio. Last week I was surprised that Monica did

not answer the question whether she knows him. So, I ask him if

her name rings a bell.

My uncle does not have to think long. He remembers Moni-

ca vividly. He had been incredibly annoyed with her. Bluntly, he

calls her a ‘brutal dyke!’ In his anger, he adds that she comes from

Scheveningen and is a vulgar woman with no manners.

Chapter Five | Warnings

41

A few years ago, she had taken some painting lessons in his

studio. She had no talent and no interest in painting either. In-

stead, Monica kept bothering him during group classes with prob-

ing questions. She wanted to know all about his contacts with the

Egyptian embassy.

Frans spent many years immersing himself in Jewish mysticism.

He also became interested in the culture that had shaped this an-

cient people and he created a series of oil paintings inspired by the

Great Pyramid and the Sphinx. Exhibitions and trips to the Land of

the Nile resulted as a matter of course in him befriending several

Egyptians, including the Minister of Transport and Tourism. 14

I tell my uncle that Monica has been working in the Military

Intelligence Service for more than seven years. He is relieved as

it confirms the suspicion she aroused in him when she was taking

lessons from him. He was dead right after all: Monica is a spy.

I also tell him about the other Defence

woman at Casema; however, he has, unfortu-

nately, never heard of Ina. About military in-

telligence and how they operate there, he can

speak volumes, though. During his time of ser-

vice in the Naval Intelligence Service (marid),

he frequently encountered vice cases. Usually,

it involved forbidden sexual contact between

Frans in the Navy

servicemen, issues that were then quite often

covered up. A name was then quickly changed

in the dossier.

Uncle Frans explicitly warns against the

dirty games played in military intelligence.

Instead, he prefers to talk about the paintings

he made during his service. For instance, one

day he had painted a portrait of Jan van Dulm,

then Head of the marid. 15 The painting was

received with praise, after which Frans was

allowed to paint the most senior officers.16 It

did not stop there. The admirals also had their

wives come by for a faithful portrait.

42

The Cover-Up General

Once home, I realise that while Monica is looking into my ante-

cedents today, I have also found out more about her. At least now

one can understand why she refused to respond to the question

whether she knows my uncle. Her earlier misbehaviour at Uncle

Frans’ studio she prefers to keep to herself.

With the new information, I can better place Monica’s intelli-

gence work. Her painting lessons in order to explore his diplomat-

ic contacts, and her work at Casema to recruit me for the position

of military analyst, point in the same direction. The penny drops:

Monica fulfils intelligence assignments by the score.

On Tuesday 21 July, I am once again called off by Casema. Telesales

has been facing overstaffing since two Defence women started

working who have a preference for my working hours.

Wednesday evening, I arrive back in Delft, where Anna informs me

that she has terminated the contract with my temp agency. This is

surprising as Randstad did not communicate anything about this.

Anna also does not explain further why she dissolved the contract.

She does however suggest I work another two hours, because

otherwise I would have cycled from The Hague to Delft for nothing.

I accept the offer and walk over to supervisor Marlies. The events

do not leave her unmoved — with tears in her eyes, she tells me the

departure has nothing to do with me. On the contrary, Casema is

very pleased with me. She has no idea why I have to leave and says

she is overwhelmed by it.

I grab a chair at Ina and Monica’s desk island. Ina, however, pro-

tests vehemently. She shouts that I have been fired. She forbids me

to sit down because I would no longer have anything to do in the

department.

Ina’s mention of ‘firing’ startles me. This is not a question of

getting fired, nor has Casema used this word. Ina’s audacity upsets

me; she only has a summer job and should not interfere with my

every move. I sit down opposite her.

One can only guess at the reason for my departure and I suspect

it has to do with Ina’s intrigues. Could it be her revenge for last

Chapter Five | Warnings

43

Friday when she was terrified while talking about her husband and

the mid?

I no longer care about being prohibited from mentioning the

profession of Ina’s husband. I bluntly state that three of us have

something to do with the Armed Forces: isn’t it a coincidence that

Monica works in Defence, Ina’s husband too, while I applied there?

Monica jumps up fiercely. She turns her head to Ina, who is sit-

ting next to her, and looks at her with a wary eye. So, apparently,

Monica did not know that besides her, another Defence woman

was deployed with us.

The revelation causes Ina to erupt in anger. She snarls about the

concurrence: ‘It’s not at all coincidental!’ She refrains from further

explanation.

When I ask Monica between a few phone calls about the intelli-

gence file relating to my Navy application, she says aloud that she

cannot say anything about it. Well, apparently she can after all. Be-

cause moments later, she whispers that she wants to speak to me in

private afterwards, in the hallway in front of the lifts.

44

The Cover-Up General

CHAPTER SIX |

CHAPTER 6

Antecedents

At eight o’clock in the evening, I clear out my desk drawer.

Anna stays with me and tells me she is dissatisfied with my

temp agency. One temp from Randstad Callflex reported

sick on the first day; the others are on holiday. Anna explains that

of the four Randstad temps, I am the only one doing his job. As a re-

sult, it was decided to continue using only the services of Teleprofs.

I say goodbye to Anna and my colleagues in a perfectly friendly

and civil way. Only Ina demurs: she refuses to wish me well and

indeed faces me with a hostile look.

I leave the department and walk to the hallway in front of the

lifts. I wait there for Monica, who explains that she is not actually

allowed to say anything about my personal file. On her own ini-

tiative, however, she does shed some light. My antecedents were

indeed the stumbling block. Although, according to the law, my

past should not have been raised at all, she nonetheless says that a

‘clean record’ is required when applying for such a job.

I am perplexed. First my character is too strong and now sud-

denly I am confronted with the opposite: my character or integri-

ty would seem to be too feeble to serve my country as an officer.

Nonetheless, I am of use to the state government as an analyst at

the mid, a highly sensitive position in which I would undoubted-

ly come into contact with state secrets. How is it possible that the

Armed Forces should approach me in such a contradictory man-

ner? And does it demonstrate integrity that the MoD examined my

past in violation of the Dutch Security Investigations Act?

Monica’s emphasis on my antecedents forces me to think back

to phases in my life that I thought I had left behind. I am not with-

out faults and have committed indiscretions at times.

Chapter Six | Antecedents

45

For example, when I worked as an escort for a while in the past,

I agreed to take part in a very controversial project of the bvd, the

Domestic Security Service of the Netherlands. It involved giving

sexual pleasure to high-ranking foreign guests.

One of the project’s organisers approached me for this in the

summer of 1992. The man, who was a friend of mine, told of the

reluctance to use the existing escort agencies in The Hague for the

diplomats. Instead, the bvd wanted to contract its own girls and

boys of a higher level. For this, I was approached. Explicitly, the