derstood better. From it, the following reconstruction can be made:

As early as 3 April 1998, I attracted the attention of the Navy dur-

ing the information meeting. Lieutenant Commander Hamaken

became suspicious when I made notes about the occupational haz-

ards faced by military personnel.

He may not have realised sufficiently that candidates want to

prepare properly. For my part, I was unaware that note-taking is

sensitive in the Armed Forces. Still, I don’t think I did anything

wrong. The fact that a soldier is expected to carry out his mili-

tary duty in spite of danger to his life is a sacrifice that deserves

attention.

Lucas explains that my serious approach at the naval barracks

raised fears that I might be an undercover journalist. It was this sus-

picion that is at the root of a series of rather bungled actions on the

part of Dutch intelligence. Only after two Defence women became

involved in this story and I was eventually confronted with their

conflicting testimonies, I decided to write down my experiences.

Hamaken had given assurances that background checks would

not be conducted until after the selection process was complete.

80

The Cover-Up General

Instead, I was subjected to an investigation without the Head of the

mid having received the necessary authorization from me. Accord-

ing to Lucas, there was nothing about me in the mid archives at the

time. There were, on the other hand, notes in my bvd file which

would be passed to the MoD.

Lucas explains that, as a result, my past work as an escort led to

discussion at Recruitment & Selection. While the bvd escort pro-

ject had to remain secret and the mid was only allowed to evaluate

my antecedents during a security screening, scandal-sensitive sto-

ries took on a life of their own.

It was precisely because of my stature that I was approached

to work for the bvd as an escort. There was a lot of praise for my

clean and healthy appearance, which was in stark contrast to that

of many drug-using prostitutes. However, when I applied to the

Navy, they looked at my qualities in a completely different way. Be-

hind my back, I was judged on having been an escort, while the

bvd had been appreciative of it.

By contracting elite escorts to act as ‘hostesses’ and ‘hosts’ for

high-ranking foreign guests, the State of the Netherlands tore open

a Pandora’s box of ethical questions. However, this is not taken

into consideration. Instead of looking at their own conduct, intelli-

gence officers prefer to focus on the lives of others.

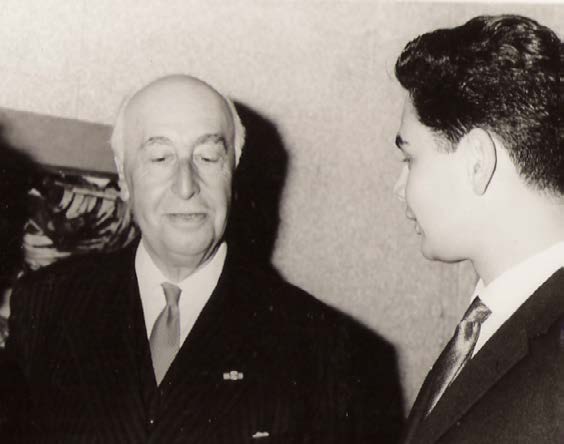

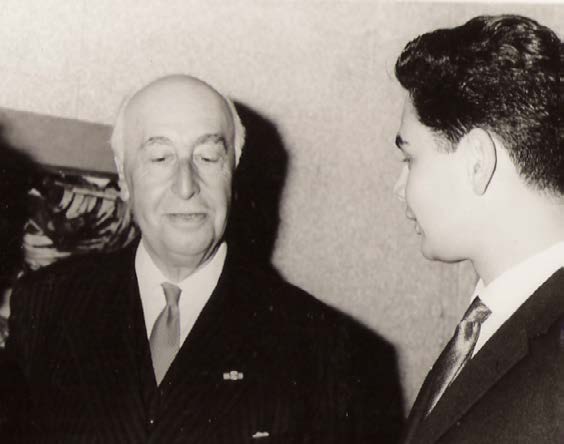

When I tell Uncle Frans about

this unsavoury interest in other peo-

ple’s private affairs, he starts talking

about his adolescence. In the 1950s,

he became friends with José Ruiz de

Arana y Bauer, the Duke of Baena y

de San Lucar la Mayor, who was the

Spanish Ambassador to the Nether-

lands.71 Several times a week, the

Duke of Baena & Frans

ambassador’s private driver would

pick him up from his parents’ home

to take him to the embassy for

dinner.

The duke supported Frans in his

Chapter Nine | Reconstruction

81

painting career and introduced him to the distinguished guests

at these dinners. It was in this way that my uncle came to know,

among others, Prince Bernhard: Queen Juliana’s husband. At the

time, he was the Inspector General of the Army and Navy.

After Frans started working for Naval Intelligence as a draftee,

he was questioned regularly about these embassy dinners. He also

had to relay all sorts of things when De Baena and he were invit-

ed to other embassies. ‘Without realising it, you’re already caught

up in it,’ he says of the espionage work he had to do, while still

under-aged.

Frans says that the marid wanted to know about the diplomats’

political views. Even Prince Bernhard, who according to Frans was

only chasing women, was denied privacy. The Royal Navy looked

for weaknesses and recorded his observations. For instance, the

secret service was intrigued as soon as he got to know about drug

use, because the dignitaries who committed these indiscretions

could be ‘nudged’ because of this.

In particular, they hoped to learn about diplomats’ inappropri-

ate sexual contacts. They were especially keen to hear about homo-

sexual encounters.

The rewards for his intelligence work were plentiful: a large

office room, luxury holidays in foreign cities, fancy hotels and

dinners — it seemed endless. Frans, known in the Navy as ‘the

handsome Dutch-Indonesian’ because of his mixed blood, enjoyed

all the privileges. Cognac and cigars! He couldn’t have had it any

better as a sailor.

However, Frans was annoyed by the constant questioning. He

particularly resented having to betray diplomats who could be

blackmailed over their conduct. Mind you, in the 1950s it was il-

legal for an adult male to have sex with a man under the age of 21.

Diplomats who slept with Frans were committing a sex crime.

At one point, when the marid asked him to have sex with a cer-

tain diplomat, he refused. In his perception, man-on-man love has

nothing at all to do with blemishes or immoral behaviour. In his

eyes, sex is about love. Why would you want to deceive men who

give themselves to you? Frans confides that he secretly protected

82

The Cover-Up General

several people from his superiors. He kept many sensitive matters

to himself.

De Baena eventually learned of his intelligence activities. There

was a great deal of consternation when the ambassador’s limou-

sine passed by the marid one day on its way to pick him up. In the

end, however, my uncle managed to cool everything down. Howev-

er, this meant covertly passing on information about the marid to

his Spanish friend.

When the marid offers him a permanent job at the end of his

military service, Frans turns it down — he finds spying and things

way too confusing. He enters the Royal Academy of Arts and

graduates cum laude in 1960. 72 He is only up for an assignment occasionally.

As for my own adolescence, in 1992 I was assured by the bvd’s

project organiser that there was an occasional need for erotic en-

tertainment late at night among our country’s distinguished guests.

By providing its own escort girls and boys, the bvd was able to fulfil

these wishes, according to the plan presented.

In the meantime, however, I have come to doubt whether the

bvd was really all that concerned about the foreign diplomats.

Does our country show its natural hospitality by providing girls

and boys for amorous pleasure? Was the government providing

prostitute students purely as a service? That the sexual encounters

were secretly paid for, organised and hence more or less set up by

the bvd should have given me pause for thought at the time.

Little did I know then that a ‘honey trap’ is a classic method

used by intelligence services worldwide. This involves a spy agency

seducing a foreign diplomat into having extramarital sex, which

is secretly photographed or filmed. After that, the diplomat is

confronted with the compromising pictures. Secret services have

learnt that sometimes it is not even necessary for their target to

be actually blackmailed. The fear of being blackmailed sometimes

already makes him comply.

I remember well how, in 1992, the intention was to find high

class escort boys and girls, in the interest of discretion. This ren-

dered existing escort agencies in The Hague of little use. Should

Chapter Nine | Reconstruction

83

‘common’ agencies be used, diplomats could potentially be black-

mailed by those. The genuine concern with which these fears

were expressed suggests that not only the escorts were misled at

the time. I suspect that the operation itself may also have been ar-

ranged under false pretences.

In retrospect, it is clear that the escort project would have been

difficult to arrange should it have been disclosed that the bvd in-

tended to use it — by secretly taking on the role of pimp — to black-

mail diplomats. If this had been brought to my attention at the

time, I would have distanced myself from the project at once.

By insisting on the importance of discretion towards diplomats,

the project seemed much safer. Organisers and escorts were able

to take part in this secret ‘security project’ with a clear conscience.

The work, as it was presented to me, appealed to me at the time.

It seemed to be quite an honour to be able to provide a pleasant

evening for high-ranking foreign guests on behalf of the govern-

ment. I would be well rewarded for the expenditure of my sexual

energy and my discretion. I was to be treated very respectfully for

the confidential services, or so I was led to believe.

At the time, I was focused on the pleasures of the business and

did not consider that sex could be used to blackmail escort clients.

That grim thought was too far from my mind.

In my naivety, I did not realise that secret services are cunning

enough to manoeuvre diplomats into compromising positions by

seducing them with hired escorts posing as hostesses (or hosts).

Nor did it occur to me that in this scenario the agents would be so

indifferent as not to inform the escorts of their shady intentions.

That girls and boys who get involved with the bvd, left or right, are

exposed to a world where violence and murder are not shunned:

no, I did not learn that at school.

Only years later did I find out that many prostitutes employed

by the kgb had been killed in the past. 73 The Navy told me honest-

ly that a soldier risks dying for his country, but when the bvd set

their sights on me as an escort, I was not told. Moreover, in 1992 I

knew little about the methods used by spy agencies to keep their

operations secret. So I missed the point that the whole discretion

84

The Cover-Up General

narrative was a perfect cover cunningly used to legitimise this highly controversial project.

Somewhat stupidly, I did not realise at the time that I was being

tricked with pretexts: what young adult would distrust his govern-

ment when it flatters him and appeals to his integrity and class?

Who would ever have thought that Dutch intelligence would violate

the very discretion that it professed to uphold? Who could have ex-

pected this betrayal?

My own escapades, no matter how trivial, were to be assessed

with the utmost prudence for security risks in a screening under

Dutch law. The mid had to keep scandal-sensitive matters to itself.

Nor is it its job to pass moral judgement. Only one thing mattered,

Lucas said: whether or not I could be blackmailed because of my

escort past.

In this context, I would like to refer to the mentality of Presi-

dent Sukarno of Indonesia. During a flight to Moscow, the head of

state was seduced by young Russian women who secretly worked

as prostitutes for the Soviet Union, Pravda writes.74 Sukarno then invited the women to his Moscow hotel room, where a grand orgy

ensued. However, two hidden cameras had been set up there and

were filming the festivities.

Afterwards the kgb showed Sukarno the porn film he had

starred in. The Russians assumed that, in any case, the Muslim

president would not want the footage to be released because it

would embarrass him. But this honey trap turned out different

than expected.

Instead, Sukarno said he was honoured by the film. He refused

to be pressured and asked the kgb for copies so that he could show

the film in cinemas in Indonesia. The statesman declared that the

Indonesian people would be very proud of him when they saw how

passionately he had made love to the lascivious Russian women.

The story goes that when Sukarno returned to Jakarta, he

showed the footage to his entire cabinet. In doing so, he exposed

the treachery of the Russians, proved that he could not be black-

mailed and set an example right away.

In the same way, I have proved that I cannot be blackmailed.

Chapter Nine | Reconstruction

85

After Monica told at Casema behind my back that I did not dare to

talk about my past, I took the presidential route and confided in

the national ombudsman. That I once decided to comply with the

far-reaching wishes of my country — is that something I should be

ashamed of?

If an official security screening had been carried out, which it

was not, there would have been no reason to withhold a Statement

of No Objection from me. If the mid had still been of the opinion

that I was a target for blackmail, I could have appealed to the Min-

ister of Defence. And in the event of a negative decision, there was

still the possibility of going to court. A judge might then have asked

why someone who was approached for a bvd project because of

his integrity, which should have eliminated the possibility of black-

mail, was rejected by the same government as open to blackmail.

One thing is clear at any rate: the assumption that I am gay met

with resistance from the Marine Corps. Lucas explains that this

elite corps rejects all gay candidates in the selection process

and keeps it secret because it violates the constitutional ban on

discrimination.

A senior Human Resources officer at the MoD, whom I met, also

explains this policy to me. When he declares his love for me, I warn

him and tell him that I have experienced untold hassles after apply-

ing for a job with his employer. In response, he says he has a mate

at the mid who handles integrity issues. He will sort it out — all I

have to do is provide my official personal details.

On the morning after 11 September 2001, the officer reports

to my home in The Hague before going to the Ministry for urgent

consultations that day, regarding the attacks in the United States.

Dressed in uniform, he enlightens me as to the illegal nature of the

personnel policy, which is used only by the Marine Corps. He also

says that Commander-in-Chief of the Army Ad van Baal is a per-

sonal friend of his, who is respected by his men because he always

stands up for them.

To sum up, two well-informed insiders independently reveal

that the Marine Corps does not allow gays to serve. In addition,

86

The Cover-Up General

both of them confirm explicitly that I was rejected due to fallacy.

Lucas says that senior MoD officials are aware of the discrimi-

natory policy: they were informed of this in secret in 2000, when

the Dutch Equal Treatment Commission investigated the overt ex-

clusion of women in the Marine Corps. 75 The Minister, it becomes

clear, appears to tolerate discrimination against women and ho-

mosexuals — on the understanding that women are openly dis-

criminated against and homosexuals are covertly discriminated

against.

One might wonder what these marines are so worried about.

Why do they classify men by sexual preference? Requiring every-

one to be of the same sexual orientation in the interest of cama-

raderie is unheard of. After all, the Corps’ right to exist as part of

the Armed Forces is to defend our freedom and the rule of law that

goes with it.

What becomes clear is that the selection psychologists have

been assigned an impossible task. After all, they had to twist and

turn to come up with an excuse for rejecting any homosexual can-

didate from joining this corps.

How is this to be resolved? Well, if the problem lies with the

Marine Corps not being able to deal with gay recruits, the obvious

explanation is that they cannot handle the candidate. This reason

for the rejection may be rather embarrassing for the elite corps,

but there is a grain of truth in it.

During the interview with psychologist Strijbosch, several

questions indicated that my past had been unearthed. This left me

feeling somewhat cornered. Despite this, I did not reveal anything

about my past, which should not have been poked into. In other

words, I didn’t break.

My character being ‘too strong’ was reason for the psychologist

Van der Pol to reject me. He then went on to speak about discrim-

ination against homosexuals within the Corps and his frustrations

with the application process. In his eyes, his military colleagues

were softies who could not hold their own. This assessment squares

with the suspicion expressed while taking notes during the infor-

mation meeting.

Chapter Nine | Reconstruction

87

That might have been the end of the story, except that it was this

strong character that the mid then recognised as an asset.

Lucas explains that my work experience and worldly lifestyle made

me sought after. Indeed, intelligence agencies have a preference

for personnel who can move easily in different environments.

The latter was confirmed years later by a friend from the night-

life scene. His background in the sex industry was well-received by

the intelligence branch of the MoD. He said he was undergoing espi-

onage training there, the secret location of which he also revealed.

My interest in international politics was also something that ap-

pealed to the mid at the time. Lucas reminds me that I once visited

the library of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to do research for a

paper on the nuclear arms race in the Middle East. 76 This was true; but I had not told him of it. The visit put me in the cross-hairs of the

bvd at the time, and they made a note of it.

Meanwhile, there was a severe shortage of analysts in the mid’s

Intelligence Department. This is clear from the report Nieuw Even-

wicht (‘New Balance’) of November 1998, in which the mid is ex-

amined. 77 Looking for background information on the mid, I was

surprised to be able to pick up a copy at the Defence Information

Centre in The Hague straight away.

The report paints a negative picture of the Intelligence Depart-

ment.78 This was the department where Monica worked and her

frustrations ran high.

Regarding the essential importance of the political-strategic

intelligence perspective, the Intelligence Department ought to

be the core of the overall mid intel turnout. … In practice, es-

pecially in the perception of employees, the department seems

to be isolated. Despite the importance of the Office of Strategic

Analysis, only 13 out of 21 analyst posts are filled. This leads to

severe frustration among staff, as it is seen as an expression of

a lack of attention and leadership on the part of the mid com-

mand. This is underlined by the turnover of managers and staff

in the department.

88

The Cover-Up General

In short, there is a clear need to increase the number of analysts in

the Intelligence Department. The MoD could have simply invited

me to come back for another visit. In a face-to-face meeting, they

could have explained to me that they would prefer to see me work-

ing as an analyst rather than as an officer.

In Delft, nevertheless, the mid resorted to ‘approaching’ me, as

secret services call it when they contact someone for recruitment.

And so it was that Monica started moonlighting at Casema during

mid working hours to persuade me to join the mid. However, Re-

cruitment & Selection was not informed. After all, it was a secret

assignment.

Meanwhile, Recruitment & Selection was stuck with yours truly.

I found to be unacceptable the way in which my application to join

the Navy was rejected. Indeed, by assuming that I would believe

the far-fetched reason for my being rejected — that is, that my char-

acter was too strong — the Navy seemed to underestimate me. As a

military man, I wanted to contribute to the defence of freedom and

democracy and also to prove my manhood for myself in the world.

The fact that the Marine Corps did not know how to deal with ho-

mosexuals was not my problem. As Recruitment & Selection had

made clear, the problem of adaptation lay with the Corps.

After pointing out to Recruitment & Selection that, regarding

the combat job, I refused to accept the cowardly assessment that

the drill sergeants would not be able to break me, they came up

with an excuse out of thin air. All of a sudden, they shifted the prob-

lem of adjustment onto me and accused me of being a drug user.

And this was while the mid went to great lengths secretly to recruit

me for the sensitive position of analyst.

It is obvious: the MoD had become entangled in its own lies. The

aforementioned report describes the chaos at the mid on page 57:

‘The allocation of tasks is […] unclear. Within the current mid, this

means asking the impossible with regards to internal coordination.’

Digging deeper, it turns out that it is not unusual to approach

potential intelligence officers in their own environment. In the late

1990s, Lucas explains, this happened more often. They were ap-

proached in the field by intelligence officers, for example, at their

Chapter Nine | Reconstruction

89

place of work or at an organisation of which they were a member.

This approach had the added benefit of observing potential em-

ployees in their natural surroundings. You could see what kind of

qualities or traits they possessed before they were invited to join

the bvd or mid.

One disadvantage: This way of recruiting is extremely cumber-

some. According to Lucas, the method had gotten out of hand on a

previous occasion. The infiltration into the office of another poten-

tial candidate caused such a stir that it confused the candidate and

he did not enter government service either.

After the out-of-control infiltration at Casema, this controver-

sial recruitment method was abandoned, Lucas said. Quite a few

candidates found the approach extremely intrusive. Using an un-

dercover agent was far too heavy a tool for its intended purpose.

The bvd describes Monica as a Scheveningen doppelgänger of

Martina Navrátilová, working in the Intelligence Department of

the mid. For years she carried out minor observation missions; she

was used to infiltrate organisations.

This information comes as no surprise. Years ago, she had tak-

en painting lessons from my uncle in order to ask him about his

diplomatic contacts. She infiltrated Casema just as easily — which

wasn’t vital to state security either.

It isn’t sensible to try and recruit someone when you behaved

improperly with one of his family members in the past, while on

an intelligence job as well. This may have been overlooked in the

preparations for Monica’s operation because Uncle Frans and I

have different surnames.

Far more interesting than Monica’s attempt to recruit me, is the

fact that Ina was sent to Casema at the same time. Ina’s infiltration

served a bigger purpose. It is true there was a severe shortage of

analysts in the Intelligence Department; however, my recruitment

was simply a pretext to get Monica to infiltrate a business environ-

ment and put her in a vulnerable position.

Lucas points out Monica was more or less being set up — I was

used as a prop for that purpose. That I was dragged in unwittingly,

90

The Cover-Up General

created a smokescreen. And the fact that Casema has nothing to do

with the MoD added to the confusion.

Over time, the mid received several complaints about the way

Monica was working, says Lucas. First, a little more background:

An undercover agent should have a new cover story at the ready

time and again. At the behest of his country, he must constant-

ly spin new lies to cover himself and deceive those around him.

These changing roles have clearly had an impact on Monica. She

tried various colleagues as a sounding board to vent her frustra-

tions. She seemed tired and fed up with all the intrigue. Maybe she

was overworked too. And so we experienced something very unu-

sual at Telesales: Monica complaining that her intelligence work

was driving her totally crazy.

Over time, she became less sharp. While Monica still kept her

assignment at my uncle’s studio to herself, at Casema she openly

dropped all pretences. Everyone was told that she worked at the

mid, and that photographic evidence of the Srebrenica tragedy was

being withheld there.

Lucas explains why it is so important that her employer should

have been able to have complete confidence in Monica: apart from

observation assignments, she also had tasks that involved getting

her hands on highly sensitive information. This included work-

ing as a liaison to the bestuursdriehoek (‘administrative triangle’) in

The Hague. This meant that as mid liaison officer she maintained

contact with this municipal advisory body, which consists of the

municipality, the police and the judiciary. In this capacity, she came

across documents from Mayor Deetman, Chief of Police Wiarda

and Chief Public Prosecutor Van Gend — the three leading figures

who later hindered the prosecution of Monica for defamation!

Monica secretly made copies of sensitive information from The

Hague triangle, Lucas said. This was possible because she had to

move them from one place to another.

According to Lucas, in the same way Monica had collected

highly sensitive documents, regarding the smuggling of hard drugs

from the Caribbean, by members of the Marine Corps.

The Public Prosecutor announced the arrest of two marines on

Chapter Nine | Reconstruction

91

this charge on 10 July 1998. They were in the very Coast Guard team

that was supposed to be fighting this particular crime in these wa-

ters. Two days earlier, their last caper, they had hidden 125 kilos of

Colombian coke in military duffel bags that were being transport-

ed by Orion aircraft from the Netherlands Antilles to the naval air

base at Valkenburg in the Netherlands. They were discovered by an

MoD mole who infiltrated the drug syndicate. The Public Prosecu-

tor’s Office also conducted observations and tapped phones.79

After the smuggling gang was busted, hard drugs became

scarce in the Netherlands. In the newspaper for the homeless in

The Hague, which I read occasionally, addicts complained about

their hopeless situation. With the drying up of the Antilles route, it

was difficult to acquire narcotics. In addition, the price of cocaine,

which was now only put on the market in small quantities by drug

mules, had risen considerably. This news from the lower depths of

society seems to indicate that marines who had received a Certif-

icate of No Objection from the mid were responsible for a signifi-

cant portion of the cocaine supply in the Netherlands.

Many more civil servants — from the top to the bottom — were

involved in the drug trade than has been revealed, Lucas explained.

Moreover, I am told that, in order to protect their interests, mp

Maarten van Traa, who was investigating the case, was killed de-

liberately in a car accident in 1997. His brakes had been tampered

with radiographically — they jammed just as he drove into a traffic

jam, according to my bvd contact.

(Years later, the former Head of the bvd, Arthur Docters van

Leeuwen, would write in his memoirs that he did not believe it was

an accident: ‘The police found nothing to suggest that his car had

been sabotaged, but I still have a bad feeling about it; it seemed too

coincidental to me.’ 80 )

Lucas says there were fears that Monica would leak the files she

had copied to the press. However, thanks to the fact that she was

under observation in Delft, it did not occur.

In tears, Monica had complained that her Marine colonel had

been sacked by the Head of the mid and that she wanted to leave

the MoD herself. Lucas has a different explanation: with Ina’s secret

92

The Cover-Up General

testimony of Monica’s violations of state secrets and the photos of

the latter’s infiltration, Monica and her rebellious superior would

have been put under pressure and forced to leave.

This way, opposition against the Srebrenica cover-up would

have been quashed. The bvd top official, who monitored this affair

so closely, revealed that he saw this as a kind of power grab within

Dutch intelligence.

Incidentally, Ina did not make it in the intelligence sector. Lucas

notes that her first undercover job, which caused so much unrest,

was also her last. Besides Monica and her Marine colonel, the op-

eration would have cost Ina her job as well.

The scandal not only affected Casema’s management and employ-

ees, but also claimed victims. Jasper’s stepfather, a kind and hard-

working man, lost his high position as a result. For Anna, being

confronted with a break-in by spies in the department she man-

aged, it was also an unpleasant experience.

Lucas reveals that during this confusing period, my phone was

tapped by the mid. After I left Casema, Jasper and I were on the

phone a lot, and we talked regularly about the situation there and

about this secret service. The content of these conversations would

have worried the mid. For example, on 4 September 1998, I told

Jasper that the recruitment operation at Casema was used in a

power struggle between generals. It appears the mid had no clue

as to how I knew that, since I had neglected to say in that particular

private conversation that it was only a suspicion that had spontane-

ously occurred to me at that moment.

Other calls also seem to have led to a certain amount of para-

noia at the mid. For example, mp Gerrit Valk called me in late Au-

gust 1998 to arrange a meeting after I had written to him on Uncle

Frans’ advice. Apparently, the mid was hugely shocked by this: Valk

specialises in military policy and was concerned with Srebrenica.

What the mid did not know at the time is that, while at the parlia-

ment building, subsequently I had a confidential conversation with

a member of Valk’s staff, about the situation in a museum in Leid-

en. This specific appointment had not been about the obscuring of

Chapter Nine | Reconstruction

93

sensitive photographs, but about the obscuring of artefacts. 81

I had never spoken to Lucas about my contact with Valk before.

The fact that he mentioned the mild panic this caused in military

circles, indicates that my phone was indeed being tapped. As far as

this phone call is concerned, Valk was also bugged. This is disturb-

ing, as his duties as an mp include oversight of the MoD, which in

turn should have no oversight of mps.

Lucas explains that over the course of many months, my phone

calls were processed into wiretap reports. Even long private con-

versations with friends about topics such as sports, dating and sex

appear to have been typed up word for word by audio editors. After

that, all the chatter is supposed to have been studied by analysts.

Instead of being concerned with state security, they appear to have

monitored meticulously the joyful lives of a few young men.

My garbage bags were also secretly taken and rifled through,

according to Lucas. From those, it is easy to deduce that I don’t

smoke, drink or take drugs. In addition, the gloved person sifting

through the smelly mess must have been able to tell from the pack-

aging that my beef burgers were from discounter Aldi.

If the mid had wanted to know my opinion regarding this spy-

ing affair, all they had to do was ask. It would have provided them

with more relevant information.

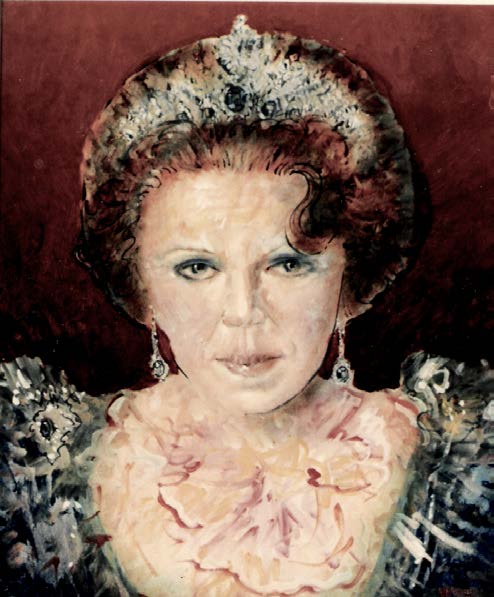

I am frank by nature. In Uncle Frans’ salon, I learnt the value

of people approaching each other with an open mind. From brick-

layer to princess, 82 from monk to call girl, from clown to general: the social status of the guests was of little importance, and their

work was not judged as good or bad. This live-and-let-live mentality

I adopted.

The mid had a hard time pigeonholing me, according to Lucas.

Defence intelligence was under the misapprehension that due to

my modest wages and social status, my network couldn’t possibly

be extensive. It puzzled them how I was able to get in touch with

the bvd and unravel the ins and outs of their operation. Add to this

a considerable amount of suspicion — not uncommon in the espio-

nage industry — and it is clear there has been a great deal of specu-

lation about my motives for wanting to join the Navy.

94

The Cover-Up General

One of the hypotheses focused on the smuggling of drugs by

marines. According to this crazy story, I applied to the Marine

Corps to infiltrate — mind you — on behalf of a rival drug gang on

the highly profitable trafficking route controlled by the Marines.

In talks with Lucas, we express our suspicion that this theory

originated from another tapped call misinterpreted by the mid. Be-

fore I hooked up with Jasper, I once dated a naughty Antillean. An

over-zealous analyst might have promptly linked me to his rogue

circle of friends, after which, on paper, I would have connections

with an Antillean gang.

Another theory is that I applied to the Marine Corps with the

audacious plan of exposing gay discrimination. The fact that I was

supported by a top gay rights lawyer after my rejection, supports

this story. But that is not true either. Call me naive, but prior to

my application, I did not expect to be discriminated against by the

Armed Forces.

The main purpose of my complaint to Ombudsman Oosting was

to clarify some confusing issues. But it made Monica jealous, says

Lucas. She reportedly felt snubbed in her ambition to become a

whistle-blower and lied during her interrogation.

Lucas points out that the mid had made a secret agreement

with Monica to support her if she discredited me. He insists that

mid Major De Ruyter conspired with Monica to make the false

statement.

In addition, Recruitment & Selection also made a false state-

ment to Oosting, Lucas confirms. Contrary to Permanent Secretary

Barth’s letter of 2 March 1999, Recruitment & Selection was said to

have been informed in advance of my background check, as be-

came clear to me immediately during the psychological interview.

If the National Ombudsman had done his job properly, he

would have exposed the lies. Unfortunately, he did not show his in-

vestigative prowess. Although, according to the bvd, the MoD was

asked why an mid officer was sent to Casema, the Ombudsman was

provided with the vague reply it was a state secret. As far as the

Ombudsman was concerned, that was the end of the matter.

A state secret is information which could endanger a country,

Chapter Nine | Reconstruction

95

should it end up in the wrong hands. Is the reason for Monica’s de-

ployment really a secret, the disclosure of which would jeopardise

the safety of us all?

That is not the case. If it had come to light that Monica had infil-

trated Casema to recruit me, the mid would have suffered a back-

lash over her bogus report.

A few weeks after I called in lawyer Gerard Spong, the Head

of the mid and his deputy both lost their jobs. According to Lu-

cas, Minister De Grave decided to dismiss them not only because

they withheld a report on right-wing extremist behaviour among

Dutchbat veterans. Reproduced here, is the aforementioned Word

document from the bvd top official and Lucas:

The mid withheld the report of [Ina] from the Minister of De-

fence. Only in July 1999 would it come into his possession.

Partly as a result of this report, on 13 July 1999, the Minister of

Defence held an in-depth interview with the Head of the mid,

General H.J. Vanderwijer, and mid Chief of Staff, Mr R. Wielin-

ga. Minister De Grave is furious with the mid command. The

discrimination against homosexuals, the forbidden infiltra-

tions, the withheld report, the revelations about the Srebrenica

photos, the tribal struggle within the mid, etc., convince him

that the mid needs to be reorganised more thoroughly than al-

ready planned.

The Minister of Defence strongly criticises the fact that the

investigation by the mid Chief of Staff was sent on his behalf,

on 2 March 1999, for which he [in casu, the Minister] could have

been prosecuted. After all, this investigation of [Monica] con-

tained pertinent lies, and the mid top brass was aware of this.

Minister De Grave deems it unacceptable that the mid com-

mand misled him and defended [Monica]. As a result, the Head

of the mid and his Chief of Staff decide to resign.

In the press, De Grave spoke only of the report on right-wing ex-

tremism, which was withheld. No mention was made of Ina’s re-

port. By not mentioning my name at all, the MoD was protecting

96

The Cover-Up General

my privacy, Lucas said. However, not having been consulted my-

self, I doubt whether my interests were taken into account.

It is no less surprising to learn that the Defence leadership has

given me a moniker. In their vernacular I am referred to as Guillo-

tine, instead of Giltay, in this case referring to the ‘severed heads’ of

the two mid executives.

No mean feat perhaps, but upon being informed of this by the

bvd, I do not jump with joy. The message is surreal, as I am not

vengeful and have not taken up the hatchet against the Defence Or-

ganisation. It is not me that caused the heads to roll; the Head of

the mid and his Chief of Staff fell on their own sword.

In principle, what I was concerned with was clarification: the

point of the whole affair seems to have been to set up Monica. She

was sent to recruit me, which was a trap. As a Dutch citizen, you

don’t expect to be confronted with such elaborate scheming.

Only now do I realise that my country has a lot to hide. The fact

that the intelligence apparatus has been so eager to use the dispro-

portionate means of infiltration in this affair says something about

its dogged determination to keep shameful matters under wraps.

A tribal war with antagonists baying for blood — I should never

have been part of that. On the contrary, from an ethical perspec-

tive, I should have been protected by the mid and bvd from se-

cret service machinations. Unsuspecting citizens like my Casema

managers and myself were put in a bizarre situation: we found our-

selves asking the authorities to clarify a genuine espionage scandal

unfolding in the Dutch lowlands. That is quite telling.

A typical whistle-blower is an employee who discloses miscon-

duct by their employer, thereby ‘betraying’ their own bosses. Be-

cause of this, whistle-blowers often struggle with their loyalties.

Although I witnessed a spy debacle, I do not fit the description

above: I never worked for the MoD and I have no complaints about

Casema. In that respect: my manager Lisa did her best to clear up

the espionage crimes that had terrified our office. She deserves

nothing but praise for this.

In my view, an operation intended to quash internal opposition

to the withholding of evidence of war crimes, should be described

Chapter Nine | Reconstruction

97

carefully and thoroughly — as this is in the public interest. This is

why I feel compelled to divulge the questionable actions of the peo-

ple involved. I have attempted to present this as objectively as pos-

sible in this exposé.

I have chosen to be discreet here and there. The fact that civ-

il servants were only too happy to tell their story did not stop me

from protecting them where necessary. On the advice of the bvd, I

have omitted some of the disclosures they themselves provided, in

the interest of my own safety and that of others.

My complaint to the National Ombudsman was looked into by

the State Attorney at law firm Pels Rijcken, Lucas reveals. This was

confirmed years later by a former employee, to whom I promised

anonymity.

However, the Armed Forces are said to have refused to disclose

the background to the case, much to Pels Rijcken’s dismay. While

I was briefed in detail by a senior intelligence officer in the Home

Office about what the MoD had been up to, the Armed Forces, so I

am told, did not dare share the case’s background with their lawyer.

After examining the documents submitted by the MoD, the

State Attorney advised to settle the case with me, so Lucas says. But

I was never approached with any proposal. The Ministry refused

to retract the false and murky statements the mid top brass made

about me. Despite an angry minister sacking the mid command,

the Ombudsman declared my complaint unfounded.

On Spong’s advice, I wanted to report the criminal offences. For

as long as possible, however, the police refused to file a report. The

bvd connects their reluctance to Monica’s former liaison job: she

knew too much. She had kept the copies of the documents collect-

ed from Mayor Deetman, Chief of Police Wiarda and Chief Prose-

cutor Van Gend, should the need arise to save her own skin. She

threatened to leak them to the media, thereby opening a can of

worms, Lucas said.

This explains why the police and judiciary in The Hague refused

to file a report and prosecute Monica.

The opposition I faced in this matter finally led me to appeal

to the Queen. Shortly after her intervention, Deetman formally

98

The Cover-Up General

admitted that his police force had bungled. But there was more going on.

Lucas reports that the National Police Internal Investigations

Department (Dutch: ‘Rijksrecherche’), the special police branch

that investigates government corruption and war crimes, conduct-

ed a criminal investigation into the affair. To this end, two police

investigators reportedly spoke to Mark and visited Casema to talk

to my former colleagues.

Lucas points out that, following investigations, the National

Police Internal Investigations Department was highly critical of

the conduct of the two Defence women at Casema. These find-

ings would in fact have cleared me completely of the phony MoD

accusations.

However, I was told the Internal Investigations Department

decided to close the case and keep it under wraps. The mid’s with-

holding of photographs of war crimes in Srebrenica was not ad-

dressed. Nor was my name cleared.

Lucas says that another miscarriage of justice at the time had

actually been put right. Police Chief René Lancee of Schiermon-

nikoog Island had been arrested by a special squad in 1996, after

his daughter had accused him of sexual abuse. Later, it turned out

that leading questioning by the National Police Internal Investiga-

tions Department had led her into giving a false statement. Accord-

ing to Docters van Leeuwen in his memoirs: Police and prosecutors

had ‘made mistake after mistake and made a mess of things’.83 As a

result, many officials and politicians were forced to resign. 84

According to Lucas, the reason for clearing Lancee’s name pub-

licly, and not mine, was partly due to his social status. They weren’t

keen on showing someone like me the same courtesy. The bvd top

official’s assessment: ‘The authorities consider your interests to be

secondary to those of the state.’

Character assassination is not uncommon. The MoD labelling me

‘mentally ill’ after having first deemed me suitable as a military

analyst, was not their only faux pas. The same thing happened to

intelligence analyst Fred Spijkers, who refused to keep a scandal

Chapter Nine | Reconstruction

99

about defective land mines under wraps. Maliciously, the Armed

Forces diagnosed him as paranoid and schizophrenic.85 Later on,

while at a branch of McDonald’s, the whistle-blower was under ac-

tual gunfire by five soldiers, stationed at the Soesterberg Air Base

next door. 86

Has the Dutch government ever considered the consequences

of this ‘human resources policy’? With such conduct, how does the

MoD intend to recruit sensible intelligence officers?

After the false mid report was issued, I came into contact with

partner secret service bvd. I kept them informed on this nationally

sensitive matter as best I could. Even if my role as an informant

was only of little consequence, I was pleased they took my testimo-

ny seriously. Also, I welcome that a lot of details of the scandal have

been exposed to me by a senior official of the bvd. That is a relief

and I am grateful to him and Lucas for their assistance.

However, the government’s refusal to clear my name, is most

unsatisfactory to me. Despite being useful as a witness for the bvd,

the State prefers to leave me to my own devices. They even choose

to commit character assassination by falsely claiming I am mental-

ly ill. Subsequently, they dismiss me as a witness to this affair. Ap-

parently, this is something I have to come to terms with. According

to the bvd chief, resistance is futile because the national interest is

at stake here.

Lucas points out the purpose of this so-called ‘diagnosis’: the

mid’s intention is to disqualify as implausible my testimony about

their intrigues. Thwarting my career — putting pressure on Casema

to dispose of me — seems to have fitted into this strategy as well.

These disruption measures were not limited to my professional

life. Among other things, I am able to prove that my boyfriend was

told to stop contacting me — he was given to understand I was un-

easy talking about my past.

Lucas explains that undermining careers and creating difficul-

ties in people’s private lives, are common intelligence tactics. This

string of measures is meant to thwart me: I must be crushed.

The realisation that my country turns its back on its own cit-

izens in such a callous way is quite a blow. It is a hell of a thing

100

The Cover-Up General

when the government interferes in their careers and private lives

and tells them that they have to put up with it in the national inter-

est. I find it tormenting that the State should assign me this fate.

Serving the interest of the government by remaining silent while

it is attempting to make your life impossible does not feel like a

noble cause.

The more I think about it, the clearer it becomes. The expec-

tation that I will allow myself to be broken inwardly and give up

ideals for an unspecified interest is misplaced. Sacrificing myself

for the sake of a cover-up goes against everything I stand for: the

pursuit of light and truth. My character was not only found strong,

it is strong. Give up? Never.

The reality, however, is murky. The pile of documents proving

that justice is on my side; an intervention by the Queen — they may

be trump cards, but they are difficult to play on this issue. Here, the

government operates clandestinely by not playing by the rules of

the game.

Outlawry is a medieval punishment that allows anything to be

done to a person, without him being protected by the rule of law.

Why is it that the Netherlands today is covertly imposing such a

punishment on its citizens? What kind of dystopia is this?

If a reader ever finds himself in the position of being thwart-

ed by his government, he will need time to come to terms with it.

He will be so disillusioned by the disruption measures that it will

become a necessity for him to fathom exactly what is going on.

He will wrestle with the question of what his country, which has

driven him into a corner, is actually doing. And if he survives the

attacks, both physically and mentally, he will need to find the right

tactics. In what way is he able to maintain himself somewhere de-

spite the opposition?

I experience this quest for answers — despite the unwavering

support of friends and family — as an individual process. Unravel-

ling the dark intrigues on my life’s path has led me to contemplate

them in silence. As a result, the disruption measures, however

grim, result in a solution-orientation in yours truly that I have

come to appreciate as invaluable. As Nietzsche noted about the

Chapter Nine | Reconstruction

101

‘war’ that constitutes our life lessons, ‘That which does not kill me

makes me stronger.’

I soon realise my position: a rather insignificant citizen facing

a supreme adversary. A counter-attack would be futile. For me

this is reason to dismiss feelings of anger as pointless and thus

neutralise them.

It is better to face the disruption measures in all their grim-

ness, without anger or self-pity — after all, I refuse to be disrupt-

ed. In my mind, however, I continue to search for truth. And my

role in the big picture quickly becomes clear: I am the louse in the

fur — too puny for a mastodon to properly defend itself against.

The more ferociously he tries to knock off the louse, the more he

hurts himself.

Of course, the battle that the Dutch State is fighting cannot be

won by one person. The Netherlands is too powerful for that. But

that is not important, as I have no ambition to force a minister to

resign or to overthrow the government. On the contrary, making a

modest contribution to citizens’ freedom — protecting the rule of

law: that is what I am all about.87

It is this task, in the face of sinister intelligence machinations,

that I take on with zeal. The fact that I’m able to dedicate myself

to my ideals — even if I won’t be wearing a beret — gives me a won-

drous satisfaction in this quagmire of deception.

Realising that the Armed Forces have entered an asymmetric

conflict naturally points to the only effective tactic for my task: my

pen can hold a mirror up to the State. Was it not Van der Pol, the

military psychologist, who pointed out that people within his or-

ganisation are vulnerable to words chosen carefully?

By mirroring them, the attacks can be evaded. Indeed, I am

convinced that the energy and momentum being used to try to

harm me will backfire on the State itself. Let’s look at this conflict

in a broader perspective than just on an individual level. What

unspoken national interest is at stake here, that my country feels

compelled to silence an unwanted witness? Whose credibility is re-

ally at risk here?

The Srebrenica tragedy plays a leading role in this affair. The

102

The Cover-Up General

fact that thousands of civilians, whom the Netherlands were sup-

posed to protect, have been shot dead has left us with a nationwide

trauma. In retrospect, the Dutch Army command should have or-

dered all Dutchbat soldiers — elite soldiers no less — to fight.

Why this unparalleled negligence? After the fall of the city,

Dutch soldiers helped to separate the Bosniak men from their

women. Why is everyone in the Netherlands being deceived about

the Srebrenica photographic film showing this assistance?

During working hours of her military job, Monica revealed at

Casema, after repeatedly introducing herself as an mid officer, that

the roll is simply withheld to protect Dutchbat veterans on the ten-

nis court or in the pub. Should the photos be published, it is after

all quite possible that they would be approached by friends in their

spare time about their role in the tragedy of Srebrenica.

The truth is disturbing: footage of an impending genocide has

been covered up so that veterans can have a pint of beer in the pub

without being disturbed. Their observations of a massacre seem

less important than the protection of their reputations, among

friends and acquaintances. The clarification of the genocide is ap-

parently not a priority for the MoD. No, their image, the good name

of the boys — that is what it is all about.

Needless to say, it is against our democratic rule of law for the

photo roll to be withheld. Nor is it in the national interest for this

deception not to be corrected after critical examination. So why is

the Dutch State still keeping the lid on the cover-up? Is the Royal

Netherlands Army perhaps too cowardly to face up to its own role

in the fall of Srebrenica — this national trauma? And does it resist

disclosure because its credibility is at stake?

Chapter Nine | Reconstruction

103

CHAPTER TEN |

CHAPTER 10

Unmasking

The question that remains is: who is behind this scandal?

Who was behind the office intrusion aimed at breaking the

intelligence opposition to the Srebrenica cover-up? Who

was steering Ina?

The answer may be found among those who have not come

to terms with the fact that most of the Dutchbat soldiers were

not ordered by their immediate superiors to fight to protect the

enclave.

On 18 April 2002, everything becomes a lot clearer to me as soon as

I set eyes on the daily Algemeen Dagblad. On the front page there is

a large colour photograph of a woman whom I know well. It’s Ina! I

wonder what the newspaper is reporting about her.88

Unlike Ina, I saw Monica occasionally. I ran into her at the pop-

ular Albert Cuyp Market and in the night-spots of Amsterdam.

Although I then try to ignore her, I can see her shaking with

fear. While I am comfortable in my skin and often shamelessly

happy, Monica is terrified. The uncomfortable situation makes me

realise that a spy in our small country is not able to go through life

in anonymity. She soon loses face.

In the newspaper picture, Ina has a facial expression I know

well. It reminds me of the fear I read in her trembling body and

face whenever her husband was mentioned. Well, the husband is

also pictured, with his hand resting on her shoulder.

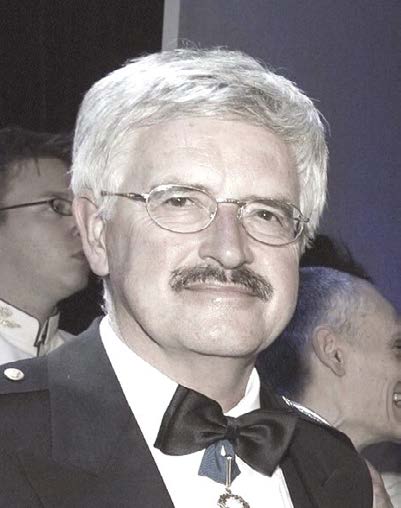

The caption reads: ‘General Van Baal, who has resigned yester-

day as Commander-in-Chief of the Army under intense political

pressure, went for an off-duty walk with his wife last night.’ I am

struck by the fact that Ina’s husband is none other than Ad van Baal,

104

The Cover-Up General

a protagonist in the Srebrenica tragedy — the second-in-command

of our army at the time.

A week earlier, the Netherlands Institute for War Documenta-

tion (niod) published the shocking investigative report Srebrenica:

a ‘safe’ area.89 In response, the Ministers Jan Pronk and Frank de Grave announced that they would be stepping down. 90 Finally, on

16 April, all ministers collectively resigned from their positions:

Prime Minister Wim Kok’s government fell.

The daily Het Financieele Dagblad comments on the collapse of the

cabinet: ‘Perhaps Kok can look everyone straight in the eye, but the

fact that it took the Netherlands seven years to come to terms with

Srebrenica morally and politically shows how difficult it is for the

Netherlands to face up to its own limitations and moral incapacity.’ 91

Press photographer Cor de Kock took the picture in the Alge-

meen Dagblad newspaper. When I call him years later, he tells me

that he found out Van Baal’s home address through his contacts

and had waited there in the hope that he would come out. But Van

Baal had already seen the paparazzo and stayed inside. Then De

Kock set a trap. He pretended to give up and drove off. But he did

not go very far. A little further on, he parked his car to stand with

his camera in a concealed position.

And so the couple went out after all. De Kock ambushed — an

ancient military tactic — the fallen general and photographed him

in the company of his horrified wife.92 As a result, the Van Baals are now on the front page of the Algemeen Dagblad.

Van Baal’s biography on the internet gives his wife’s full name.

Apparently, Ina combined a false first name with her real maiden

name during her undercover assignment.

The newspaper picture makes me think about Ina’s behaviour.

From my very first meeting with her, I knew something was wrong.

Now it turns out that my intuition was right.

As the spy intrigue had scared Casema, I call the cable compa-

ny. In a friendly conversation with Mr Hartogs, I tell him about the

newspaper photo.93

Earlier, the bvd had informed me about Ina’s identity. At the

time, though, I found it hard to believe that she was actually a

Chapter Ten | Unmasking

105

general’s wife. Surely it is beyond words for a general to use his

wife as a spy for his personal career interests. How can they be this

meshugge in the Dutch Army?

The publication of the photo confronts me with the truth and

removes the last doubts about the identity of my former colleague.

As the final pieces of the puzzle fall into place, I am getting closer

to the bottom of this cover-up scandal, in which sensitive photo-

graphs play a prominent role.

I have never been trained as an analyst. Perhaps not all of the

details are completely accurate, but these are my findings:

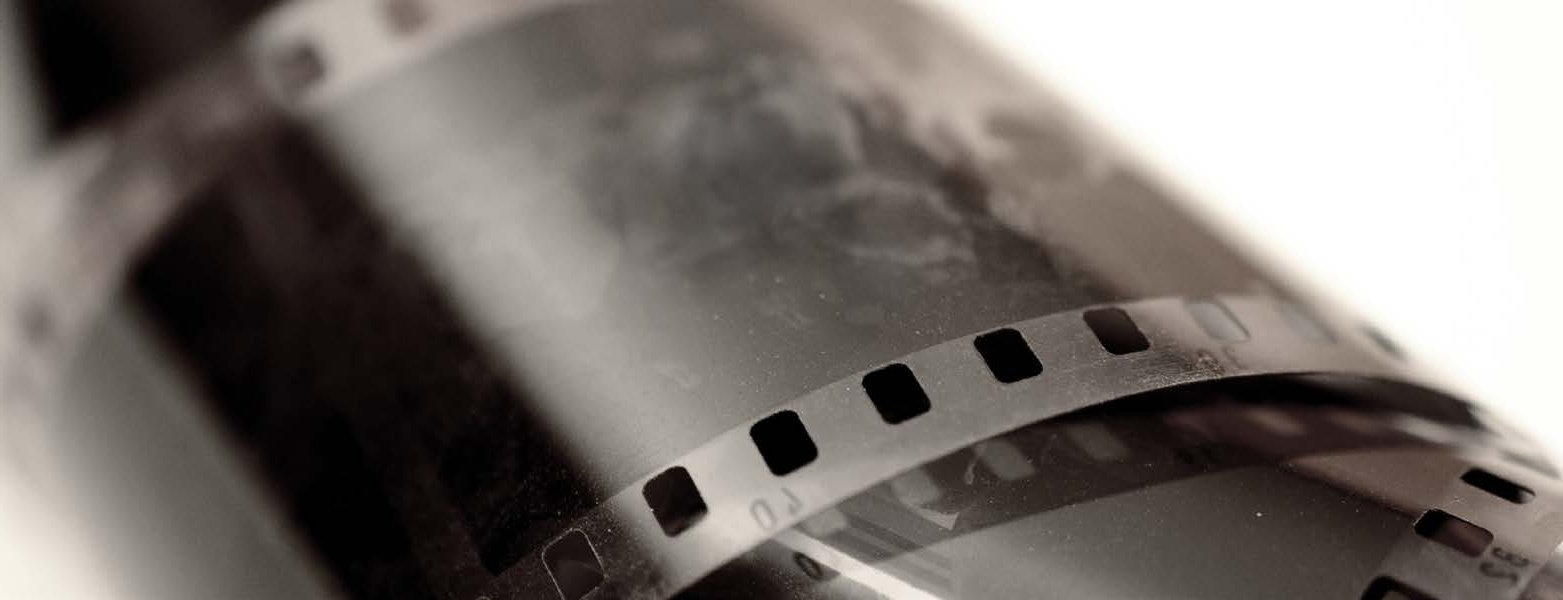

1. On 13 July 1995, three Dutchbat servicemen take photographs

of nine murdered Bosniaks in the fallen town of Srebrenica.

Lieutenant Koster stands among the bodies to show the world

the war crimes of the Bosnian Serbs. The three even risk their

lives, as they are shot at by Serbian soldiers immediately after

taking the photos. However, the Dutchmen manage to escape

and bring the photo roll to safety.

But the mid decides to cover up the footage. Indeed, the Sre-

brenica roll of film has a dark side.

The footage also shows Dutchbat soldiers aiding the Serbs

in the illegal deportation of the population. Also, they helped

to separate the men from their wives and children. The inten-

tion may have been to protect them from violence and robbery.

However, this can also be interpreted in another way, namely as

participation in acts of preparation for genocide.

Collaborating in deportation and separation can’t stand the

light of day. The Srebrenica photo roll is covered up for fear of

negative publicity.

2. On 15 July 1998, an intruder takes pictures of mid officer Monica

at a business premises in the Dutch polder. She is photographed

in the midst of her colleagues at Casema to prove that she has

infiltrated the company illegally. The flashes of light attract at-

tention: the intruder is chased by a worried helpdesk employee

but manages to escape.

106

The Cover-Up General

Monica and her intelligence boss — a Marine colonel — are

put under pressure with the photos and leave the mid. But then

the incident at Casema is covered up as there is a dark side to

this story as well.

Monica and her boss had been against the cover-up of the

Srebrenica photo roll. In doing so, they made an enemy of the

Army command, who set a trap for them. Monica was lured into

infiltrating Casema so that she could be secretly observed by

Ina. Of course, the latter’s infiltration is no less controversial

than Monica’s. For example, Ina helped the photographer by

stealing an access pass for him. His intrusion can’t stand the

light of day, and the ‘Casema photo roll’ is also hidden away.

3. On 17 April 2002, Cor de Kock photographs three-star General

Ad van Baal in civilian clothes in front of his residence. He is out

of a job: earlier that day, he was forced to resign as Commander-

in-Chief of the Army due to the controversy surrounding his

role in Srebrenica. Next to him is his wife — and I recognise her

as Ina: the mole in Casema.

Below the press photo is an article by crime reporter Bert Huisjes,

headlined ‘Wonder boy Van Baal turned cover-up general’.94 Huis-

jes writes: ‘What was wrong with Van Baal? A lot, and the Minister

knew it. … For example, in the months following the tragedy, he

investigated the functioning of Dutchbat, but did not inform the

Minister at the time, Voorhoeve. He also came up with the idea of

softening the sharp edges of the information from the Dutchbat

soldiers’ debriefing. All conversations were stamped ‘confidential’,

allowing the army to determine what could and, more importantly,

what could not be made public.’

The Algemeen Dagblad continues: ‘It turned out to be a pattern,

especially when a withheld statement that Dutchbat had signed in

July 1995 at the request of the Serbs also later surfaced. The Nether-

lands had committed itself to ensuring that the deportation of ref-

ugees was carried out correctly. The fax disappeared into a drawer

of Van Baal and only came out years later.’

Chapter Ten | Unmasking

107

Organigram | Casema workfloor

Telesales

108

The Cover-Up General

Defence workfloor

Military Intelligence

Key to infiltrations:

Military Intelligence

Van Baals & henchman

Investigation officer

(positions held in July 1998)

Chapter Ten | Unmasking

109

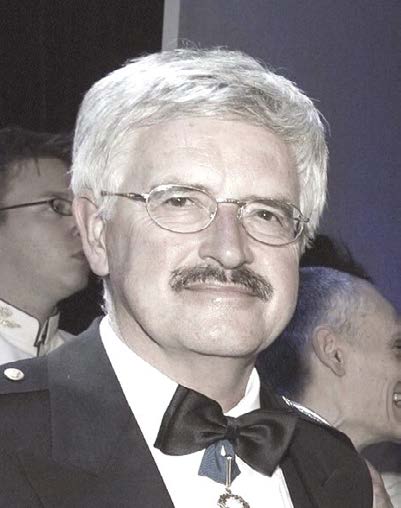

Outgoing Minister De Grave declares that

Van Baal ‘can no longer function properly in

the interests of the Royal Netherlands Army in

the light of the public discussion following the

niod report and the questions that have arisen

in the process about the functioning of the Ar-

my’s top command at the time, of which he was

Minister De Grave

a member as Deputy Commander-in-Chief.’ 95

De Grave also explains that he can no

longer take responsibility for the ongoing de-

ceit in his department. His reason for resign-

ing is that there is an unwillingness at the

Army command to keep Parliament properly

informed. 96

110

The Cover-Up General

CHAPTER ELEVEN |

CHAPTER 11

Integrity

Because he moved to Amsterdam, Gerard Spong transferred

my case to a colleague who had stayed behind in The Hague.

That brought me a new lawyer: Anousja Wladimiroff, who

works in the prestigious criminal law firm of her father, Mikhail

Wladimiroff.

Spong planned to file an Article 12 suit on my behalf, which

would allow me to appeal Chief Public Prosecutor Van Gend’s deci-

sion not to prosecute Monica. 97 However, Wladimiroff Jr. was less

willing to stand by me. It was only on 7 March 2001, after I had writ-

ten insisting on her professional assistance, that she finally com-

menced proceedings before the Court of Appeal in The Hague. 98

A year and a half later, on 13 November 2002, the court hearing

takes place.99 At the Palace of Justice I meet my lawyer for the first time — she refused to make any kind of appointment with me before the hearing. Monica is not summoned. Three judges sit across

from me in the courtroom. Members of the public have just been

asked to leave: the hearing is in closed session.

Wladimiroff presents an account that in no way does justice

to this intelligence scandal. She does not mention, for example,

that Chief Public Prosecutor Van Gend may have spared Monica

because, as a former liaison, she could put pressure on him with

sensitive documents. Wladimiroff also fails to mention that Moni-

ca disclosed state secrets at Casema by complaining that the Dutch

government is withholding photographs of Serbian war crimes.

Despite my explicit request, Wladimiroff Jr. refused to inves-

tigate the background of this case. Simply requesting the police

records on the unauthorised entry into Casema — which revealed

Chapter Eleven | Integrity

111

Monica’s double life as an mid officer and Casema employee — was

too much for my lawyer. 100 In her opinion, these matters were not

related to the Article 12 proceedings.101

On the other hand, my law firm is spending a great deal of time

and energy in providing assistance to Serbian war criminals. My

city of birth and residence, which is known as the ‘International

City of Peace and Justice’, is small. For example, Wladimiroff Sr.

assisted none other than Slobodan Milošević, the former Serbian

president indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the

Former Yugoslavia, on charges including genocide in Bosnia.102

As soon as Judge President De Vries gives me the floor, I declare

that the mid has thwarted me both at work and in my private life.

Here, I am not referring so much to the events at Casema, but main-

ly to more disturbing disruption measures that took place after 1998.

In the Court of Appeal, however, I am not elaborating on these

threats, because they can hardly be proven. Indeed, when the in-

telligence agencies target someone, they prefer to do so in a way

that makes it difficult for the person concerned to complain about

it. You will not receive any proof of the threat. No, it is my expe-

rience that secret services have a preference for shadowy, almost

incomprehensible machinations. I will describe one threat here:

Back in October 2000, a Frenchman contacted me over the in-

ternet. He worked as a concierge in a four-star hotel in Paris and

wanted to show me his city. The man also offered me accommoda-

tion and food. 103 But I had my doubts, especially when I saw a bbc

documentary on tv about the death of Princess Diana. The docu-

mentary explained that hotel concierges in Paris work for French

intelligence by default. After all, a concierge is simply a useful

source of information.

After I enquired, Lucas warned me about the plan by French

secret service agents to plant hard drugs in my rucksack during

the train journey. There would also be a border inspection of my

high-speed train, so I could be arrested on the spot for smuggling.

Lucas further explained to me that foreign intelligence agencies do

often solve problems for each other. In this case, it was a friendly

112

The Cover-Up General

service provided by French military intelligence, the General Di-

rectorate for External Security (dgse), at the request of their Dutch

counterparts who wanted to get rid of me.

I am immensely grateful to the top official of the bvd. With-

out his warning, I might have only seen Paris from behind bars.

It would certainly have extended my holiday, as drug smuggling in

France carries a prison sentence of up to thirty years.

The thought of spending my days in foreign captivity, entire-

ly innocent, is disturbing. I have seen drug smugglers eliminate

an unwanted witness in American television series. But that mil-

itary personnel in the Dutch MoD should come up with a plan to

have a Dutchman imprisoned outside the country’s borders, using

a friendly nation to do so, is almost beyond my imagination. Are

cover-ups shielded in our part of the world by making witnesses

stand trial for crimes they did not commit?

Former British secret agent Richard Tomlinson describes in

his memoirs how intelligence agencies thwart individuals.104 He reveals the way in which a secret service can very easily put a person under lock and key by planting drugs in their house and then

arresting them.

It is clear that the mid has already shown its dark side in this

affair. In addition, the dgse has been notorious for its ruthlessness

since its 1985 bombing of the Greenpeace activist ship Rainbow

Warrior, killing one Dutchman. 105 We can assume that the bvd’s

information was correct. I cancelled my trip.

When it comes to taking potentially compromising trips to Par-

is, Uncle Frans has some stories to tell. Of course, it was not for

nothing that he was treated to luxury holidays by the Naval Intel-

ligence Service during his military service. No, whenever he went

to Paris, he had to deliver something in person to a spy working

there. And refusal was out of the question, because then the jaunt

was cancelled.

My uncle tells me that, despite his doubts, he made the jour-

neys. Having to deliver secret packages abroad to people he did

not know was obviously not kosher. What was in these parcels that

couldn’t be sent by post?

Chapter Eleven | Integrity

113

Uncle Frans did not think much of it at the time, but he was

sent off as a tourist: his uniform stayed in the wardrobe. And he

was allowed to bring his future wife Norma with him. This set-up

shows cunning. Indeed, by disguising the shady military trips as

private holidays, the marid could claim ignorance should customs

officials discover a package.

Fortunately, my uncle, aunt and I have never been caught with

contraband we knew nothing about.

In the Court of Appeal, Attorney-General A.J.M. Kaptein speaks

after me. She is supposed to defend the Chief Public Prosecutor’s

decision to turn a blind eye to the fact that I was being antagonised

by the mid. Yet as soon as she talks about this, her voice cracks.

Immediately I see three judges turning their heads in amazement

at Kaptein, who acts out of character by showing that my story

moves her.

Judge De Vries also shows that he can empathise with me. Dur-

ing the hearing he tells me that I can bring a civil case against

Monica.

A month later, my complaint is rejected. I receive a copy of the

decision of the Court of Appeal by post:106 ‘The Court finds that,

in the present case, it is not possible to determine whether the de-

fendant’s statements were made with the intention of making them

public. For this reason, the offences of libel or slander cannot be

established.’

Lucas points out to me that mid Major De Ruyter, mid Chief of

Staff Wielinga and Permanent Secretary Barth committed forgery

with the mid report and Barth’s letter of 2 March 1999. This con-

cerns a crime more serious than defamation. Furthermore, unlike

slander, forgery is not an offence dependent on being reported by

an individual, which means that the Ministry of Justice can prose-

cute without me reporting it. However, it seems that no one in the

Public Prosecutor’s Office is taking this up.

After the verdict, Wladimiroff Jr. advises me by phone of the

costly possibility of filing a civil suit against Monica. However, al-

most four years have passed since the former mid officer lashed

114

The Cover-Up General

out during her interrogation, as the legal proceedings are moving

slowly in this case. So my decision is not to spend any more energy

on Monica.

After I recognised Ina in the front-cover picture of the Algemeen

Dagblad, it dawned on me that Van Baal was the mastermind be-

hind this cover-up affair. Would it not be brave to go after this gen-

eral? I toy with the idea. Yet I leave it at that, partly because he has

already stepped down under intense pressure. And partly because

the commitment of my lawyers is not satisfactory.

In addition to Gerard Spong, I also contacted the membership

service of the fnv trade union, which on 28 May 2001 referred

me to Ben Beelaard of the Valkenboslaan legal collective in The

Hague.107 I accurately described the situation for him.108 But for months no concrete steps were taken. Even the fnv denounced

the ‘long processing time’,109 after which Beelaard sent the dossier back to the union for further processing.110

The fact is that most of the key players have left the positions

they occupied during this affair. For example, the daily De Telegraaf

wrote on 27 April 2001 that three directors of Recruitment & Se-

lection in the Armed Forces had been removed from their posts

with immediate effect. The Director General, Colonel Knoop, his

deputy, Lieutenant Colonel Van Gassen, and the Head of the Selec-

tion Department, Lieutenant Colonel Luurs, had to leave. The rea-

son for this: their ‘failed management’. ‘In addition, the working

atmosphere between the managers was not optimal.’ 111 There were

‘a number of problems’, writes the daily nrc Handelsblad.112

Lucas tells me that in the directors’ letters of resignation, the

handling of my application was listed as a secondary reason for

dismissal. Obviously, there’s a lot wrong with the MoD’s selection

policy: you don’t just send three directors home.

In addition to Recruitment & Selection, the mid is also making

a break with the scandals of the past. In 2002, the secret service

is thoroughly reorganised and given a new name: Military Intelli-

gence and Security Service, abbreviated mivd.

With the dismissals and reorganisations at the MoD, I can

distance myself more from the abuses. However, my friends tell

Chapter Eleven | Integrity

115

me that this affair will never die down — it will always be topical.

After all, this scandal is intertwined with evidence of war crimes.

A new, distinctive coat of arms is designed for

the mid’s successor, the mivd. The secret ser-

vice proudly declares: ‘The armorial shield of

the Military Intelligence and Security Service

(mivd) has the Egyptian sphinx at its centre.

Here, the sphinx symbolises the knowledge

and wisdom of the mivd.’ 113

This explanation, however, shows a mis-

understanding of the ancient Egyptian world.

In fact, the sphinx served as a temple guard in

pharaonic Egypt. It did not possess the cov-

eted knowledge and wisdom that resided in

Armorial shield mivd

the temple behind it, but merely guarded it.

So the sphinx does not symbolise knowledge

and wisdom in any way, but symbolises — and

this is not insignificant for the mivd — the need

to be careful. After all, a military intelligence

and security service would be wise not to use

an armorial shield that can be easily cracked.

In the autumn of 2004, I happen to read in the newspaper that Van

Baal has been rehabilitated. Although he had been forced to resign

in April 2002, he had quietly returned a few months later. He sim-

ply went back to work for the MoD.

Van Baal is now working as the Inspector General of the Armed

Forces (igk).114 This opens up a new perspective because, as igk,

he is the highest trustee of the MoD. Within the Dutch Armed Forc-

es, the precise role he performs requires him to have the utmost

personal integrity. He is responsible for restoring trust in individu-

al cases where it has been damaged.

This is convenient. The fact that the Armed Forces have slan-

dered my character after first praising it raises the question of how

116

The Cover-Up General

much integrity the MoD actually has. By writing to the Inspector General, it is now up to Van Baal to lead by example. He can

demonstrate the character that makes one a three-star general in

the Armed Forces.

I am curious to know Inspector General Van Baal’s position on

the Defence crimes committed at his wife’s former workplace. How

much personal courage does this general have? How does he inter-

pret concepts such as incorruptibility and uprightness?

My recruitment as a military analyst was not exactly by the book

— indeed, I was undeniably disadvantaged. I offer Van Baal, in his