CHAPTER IV.

THE SOCIETY OF MARCELLA.

The council which was held in Rome in 382 with the intention of deciding the cases of various contending bishops in distant sees, especially in Antioch where two had been elected for the same seat—a council scarcely acknowledged even by those on whose behalf it was held, and not at all by those opposed to them—was chiefly remarkable, as we have said, from the appearance for the first time, as a marked and notable personage, of one of the most important, picturesque, and influential figures of his time—Jerome: a scholar insatiable in intellectual zeal, who had sought everywhere the best schools of the time and was learned in all their science: and at the same time a monk and ascetic fresh from the austerities of the desert and one of those struggles with the flesh and the imagination which formed the epic of the solitary. It was not unnatural that the régime of extreme abstinence combined with utter want of occupation, and the concentration of all thought upon one's self and one's moods and conditions of mind, should have awakened all the subtleties of the imagination, and filled the brooding spirit with dreams of every wild and extravagant kind; but it would not occur to us now to represent the stormy passage into a life dedicated to religion as filled with dancing nymphs and visions of the grossest sensual enjoyment—above all in the case of such a man as Jerome, whose chief temptations one would have felt to be of quite another kind. This however was the fashion of the time, and belonged more or less to the monkish ideal, which exaggerated the force of all these lower fleshly impulses by way of enhancing the virtue of him who successfully overcame them. The early fathers all scourged themselves till they were in danger of their lives, rolled themselves in the snow, lay on the cold earth, and lived on a handful of dried grain, perhaps on the grass and wild herbs to be found in the crevices of the rocks, in order to get the body into subjection: which might have been more easily done, we should have supposed, by putting other more wholesome subjects in the place of these visionary temptations, or filling the vacancy of the hours with hard work. But the dulness of an English clown or athlete, in whom muscular exercise extinguishes all visions, would not have been at all to the mind of a monkish neophyte, to whom the sharpest stings of penitence and agonies of self-humiliation were necessary, whether he had done anything to call them forth or not.

Jerome had gone through all these necessary sufferings without sparing himself a pang. His face pale with fasting, and his body so worn with penance and privation that it was almost dead, he had yet felt the fire of earthly passions burning in his soul after the truest orthodox model. "The sack with which I was covered," he says, "deformed my members; my skin and flesh were like those of an Ethiop. But in that vast solitude, burnt up by the blazing sun, all the delights of Rome appeared before my eyes. Scorpions and wild beasts were my companions, yet I seemed to hear the choruses of dancing girls."

Finding no succour anywhere, I flung myself at the feet of Jesus, bathing them with tears, drying them with the hair of my head. I passed day and night beating my breast, I banished myself even from my cell, as if it were conscious of all my evil thoughts; and, rigid against myself, wandered further into the desert, seeking some deeper cave, some wilder mountain, some riven rock which I could make the prison of this miserable flesh, the place of my prayers.

Sometimes he endeavoured to find refuge in his books, the precious parchments which he carried with him even in those unlikely regions: but here another temptation came in. "Unhappy that I am," he cries, "I fasted yet read Cicero. After spending nights of wakefulness and tears I found Plautus in my hands." To lay aside dramatist, orator, and poet, so well known and familiar, and plunge into the imperfectly known character of the Hebrew which he was learning, the uncomprehended mysteries and rude style of the prophets, was almost as terrible as to fling himself fasting on the cold earth and hear the bones rattle in the skin which barely held them together. Yet sometimes there were moments of deliverance: sometimes, when all the tears were shed, gazing up with dry exhausted eyes to the sky blazing with stars, "I felt myself transported to the midst of the angels, and full of confidence and joy, lifted up my voice and sang, 'Because of the savour of thy ointments we will run after thee.'" Thus both were reconciled, his imagination freed from temptation, and the poetry of the crabbed books, which were so different from Cicero, made suddenly clear to his troubled eyes.

This was however but a small part of the training of Jerome. From his desert, as his spirit calmed, he carried on a great correspondence, and many of his letters became at once a portion of the literature of his time. One in particular, an eloquent and oratorical appeal to one of his friends, the Epistle to Heliodorus, with its elaborate description of the evils of the world and impassioned call to the peace of the desert, went through the religious circles of the time with that wonderful speed and facility of circulation which it is so difficult to understand, and was read in Marcella's palace on the Aventine and learnt by heart by some fervent listeners, so precious were its elaborate sentences held to be. This letter boldly proclaimed as the highest principle of life the extraordinary step which Melania, as well as so many other self-devoted persons, had taken—and called every Christian to the desert, whatever duties or enjoyments might stand in the way. Perhaps such exhortations are less dangerous than they seem to be, for the noble ladies who read and admired and learned by heart these moving appeals do not seem to have been otherwise affected by them. Like the song of the Ancient Mariner, they have to be addressed to the predestined, who alone have ears to hear. Heliodorus, upon whom all that eloquence was poured at first hand, turned a deaf ear, and lived and died in peace among his own people, among the lagoons where Venice as yet was not, notwithstanding all his friend could say.

"What make you in your father's house, oh sluggish soldier?" cried that eager voice; "where are your ramparts and trenches, under what tent of skins have you passed the bitter winter? The trumpet of heaven sounds, and the great Leader comes upon the clouds to overcome the world. Let the little ones hang upon other necks; let your mother rend her hair and her garments; let your father stretch himself on the threshold to prevent you from passing: but arise, come thou! Are you not pledged to the sacrifice even of father and mother? If you believe in Christ, fight with me for His name and let the dead bury their dead." There were many who would dwell upon these entreaties as upon a noble song rousing the heart and charming the ear, but the balance of human nature is but rarely disturbed by any such appeal. Even in that early age we may in the greater number of cases permit it to move all hearers without any great fears for the issue.

Jerome, however, did not himself remain very long in his desert; he was invaded in his very cell by the echoes of polemical warfare drifting in from the world he had left: and was called upon to pronounce himself for one side or the other, while yet, according to his own account, unaware what it was all about. He left his retirement unwillingly after some three years, quoting Virgil as to the barbarity of the race which refused him the hospitality of a little sand, and plunged into the fight at Antioch between contending bishops and parties, the heresy of Apollinaris, and all the rage of religious polemics. It was probably his intimate acquaintance with all the questions so strongly contested in the East, and his power of giving information on points which the Western Council could only know at second hand, which led him to Rome on the eve of the Council already referred to, called by Pope Damasus, in 382. The primary object of this Council was to settle matters of ecclesiastical polity, and especially the actual question as to which of the competitors was lawful bishop of Antioch, besides other questions concerning other important sees. It was no small assumption on the part of the bishops of the West, an assumption supported in those days by no dogma as to the supremacy of the Bishop of Rome, to interfere in the affairs of the East to this extent. And it was at once crushed by the action of the Church in the East, which immediately held a council of its own at Constantinople, and authoritatively decided every practical question. Jerome was the friend of all those bishops whose causes would have been pleaded at Rome, had not their own section of the Church thus made short work with them: and this no doubt commended him to the special attention of Damasus, even after these practical questions were set aside, and the heresy of Apollinaris, which had been intended to be treated in the second place, was turned into the only subject before the house. Jerome was deeply learned on the subject of Apollinaris too. It was on account of this new heresy that his place in Egypt had become untenable. His knowledge could not but be of the utmost importance to the Western bishops, who were not as a rule scholars, nor given to the subtle reasoning of the East. He was very welcome therefore in Rome, especially after the illness of the great Ambrose had denuded that Council, shorn of so much of its prestige, of almost the only imposing name left to it. This was the opportunity of such a man as Jerome, in himself, as we have said, still not much different from the many young religious adventurers who scoured the world. He was already, however, a distinguished man of letters: he was known to Damasus, who had baptized him: he had learning enough to supplement the deficiencies of an entire Council, and for once these abilities were fully appreciated and found their right place. He had scarcely arrived in Rome when he was named Secretary of the Council—a temporary office which was afterwards prolonged and extended to that of Secretary to the Pope himself: thus the stranger became at once a functionary of the utmost importance in the proceedings of the See of Rome and in its development as a supreme power and authority in the Church.

There is something strangely familiar and quaint in the appearance, so perfectly known to ourselves, of the gathering of a religious congress, convocation, or general assembly, when every considerable house and hospitable family is moved to receive some distinguished clerical visitor—which thus took place in Rome in the end of the fourth century, while still all was classic in the aspect of the Eternal City, and the altars of the gods were still standing. The bishops and their trains arrived, making a little stir, sometimes even at the marble porticoes of great mansions where the master or mistress still professed a languid devotion to Jove or Mercury. Jerome, burnt brown by Egyptian suns, meagre and sinewy in his worn robe, with a humble brother or two in his train, accepted, after a little modest difficulty, the invitation or the allotment which led him to the Aventine, to the palace of Marcella, where he was already well known, and where, though his eyes were downcast with a becoming reserve at the sight of all the ladies, he yet felt it right to follow the example of the Apostle and industriously overcome his own bashfulness. It was not perhaps a quality very strong in his nature, and very soon his new and splendid habitation became to the ascetic a home more dear than any he had yet known.

It is curious to find how completely the principle of the association and friendship of a man and woman, failing closer ties, was adopted and recognised among these mystics and ascetics, without apparent fear of the comments of the world, or any of the self-consciousness which so often spoils such a relationship in ordinary society. Perhaps the gossips smiled even then upon the close alliance of Jerome with Paula, or Rufinus with Melania. There were calumnies abroad of the coarsest sort, as was inevitable; but neither monk nor lady seem to have been affected by them. It has constantly been so in the history of the Church, and it is interesting to collect such repeated testimony from the most unlikely quarter, to the advantage of this natural association. Women have had hard measure from Catholic doctors and saints. Their conventional position, so to speak, is that of the Seductress, always studying how to draw the thoughts of men away from higher things. The East and the West, though so much apart on other points, are at one in this. From the anguish of the fathers in the desert to the supposed difficulties of the humblest ordinary priest of modern times, the disturbing influence is always supposed to be that of the woman. Gruesome figure as he was for any such temptation, Antony of Egypt himself was driven to extremity by the mere thought of her: and it is she who figures as danger or as victim in every ultra-Protestant plaint over the condition of the priest (except in Ireland, wonderful island of contradictions! where priests and all men are more moved to fighting than to love). Yet notwithstanding there has been no founder of ecclesiastical institutions, no reformer, scarcely any saint, who has not been accompanied by the special friendship and affection of some woman. Jerome, who was so much the reverse, if we may venture to use these words, of a drawing-room hero, a man more used to vituperation than to gentleness of speech, often harsh as the desert from which he had come, was a notable example of this rule. From the time of his arrival on the Aventine to that of his death, his name was never dissociated from that of Paula, the pious lady par excellence of the group, the exquisite and delicate patrician who could scarcely plant her golden shoe firmly on the floor, but came tottering into Marcella's great house with a slave on either side to support her, in all the languid grace which was the highest fashion of the time. That such an example of conventional delicacy and luxury should have become the humble friend and secretary of Jerome, and that he, the pious solitary, acrid with opposition and controversy, should have found in this fine flower of society his life-long companion, both in labour and life, is more astonishing than words can say.

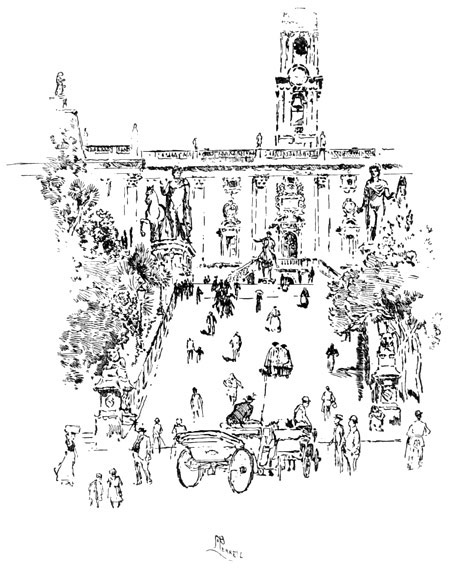

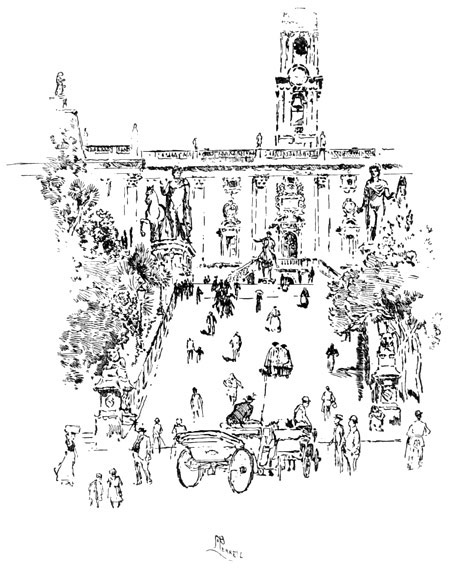

THE STEPS OF THE CAPITOL.

His arrival in Marcella's hospitable house, with its crowds of feminine visitors, was in every way a great event. It brought the ladies into the midst of all the ecclesiastical questions of the time: and one can imagine how they crowded round him when he returned from the sittings of the Council—perhaps in the stillness of the evening after the dangerous hour of sunset, when all Rome comes forth to breathe again—assembling upon the marble terrace, from which that magical scene was visible at their feet: the long withdrawing distance beyond the river, out of which some gleam might be apparent of the great church which already covered the tombs of the Apostles, and the white crest of the Capitol close at hand, and the lights of the town scattered dimly like glowworms among the wide openings and level lines of classical building which made the Rome of the time. The subjects discussed were not precisely those which the lighter conventional fancy, Boccaccio or Watteau, has associated with such groups, any more than the dark monk resembled the troubadour. But they were subjects which up to the present day have never lost their interest. The debates of the Council were chiefly taken up with an extremely abstruse heresy, concerning the humanity of our Lord, how far the nature of man existed in him in connection with the nature of God, and whether the Redeemer of mankind had taken upon himself a mere ethereal appearance of flesh, or an actual human body, tempted as we are and subject to all the influences which affect man. It is a question which has arisen again and again at various periods and in various manners, and the subtleties of such a controversy have proved of the profoundest interest to many minds. Jerome was not alone to report to those eager listeners the course of the debates, and to demolish over again the intricate arguments by which that assembly of divines wrought itself to fever heat. The great Bishop Epiphanius, the great heresy-hunter of his day—who had fathomed all the fallacious reasonings of all the schismatics, and could detect a theological error at the distance of a continent, in whatever garb it might shield itself—was the guest of Paula, and no doubt, along with his hostess, would often join these gatherings. The two doctors thus brought together would vie with each other in making the course of the controversy clear to the women, who hung upon their lips with keen apprehension of every phrase and the enthusiastic partisanship which inspires debate. There could be no better audience for the fine-drawn arguments which such a controversy demands. How strange to think that these hot discussions were going on, and the flower of the artificial society of Rome keenly occupied by such a question, while still the shadow of Jove lingered on the Capitol, and the Rome of the heathen emperors, the Rome of the great Republic, stood white and splendid, a shadow, yet a mighty one, upon the seven hills!

Before his arrival in Rome, Jerome had been but little known to the general world. His name had been heard in connection with some eloquent letters which had flown about from hand to hand among the finest circles; but his true force and character were better known in the East than in the West, and it was in part this Council which gave him his due place in the ranks of the Church. He was no priest to be promoted to bishoprics or established in high places. He had indeed been consecrated against his will by an enthusiastic prelate, eager to secure his great services to the Church; but, monk and ascetic as he was, he had no inclination towards the sacerdotal character, and had said but one mass, immediately after his ordination, and no more. It was not therefore as spiritual director in the ordinary sense of the words that he found his place in Marcella's house, but at first at least as a visitor merely and probably for the time of the Council alone. But the man of the desert would seem to have been charmed out of himself by the unaccustomed sweetness of that gentle life. He would indeed have been hard to please if he had not felt the attraction of such a retreat, not out of, but on the edge of, the great world, with its excitements and warfare within reach, the distant murmur of the crowd, the prospect of the great city with its lights and rumours, yet sacred quiet and delightful sympathy within. The little community had given up the luxuries of the age, but they could not have given up the refinements of gentle breeding, the high-born manners and grace, the charm of educated voices and cultivated minds. And there was even more than these attractions to gratify the scholar. Not an allusion could be made to the studies of which he was most proud, the rugged Hebrew which he had painfully mastered, or ornate Greek, but some quick intelligence there would take it up; and the poets and sages of their native tongue, the Cicero and Virgil from whom he could not wean himself even in the desert, were their own literature, their valued inheritance. And not in the most devoted community of monks could the great orator have found such undivided attention and interest in his work as among the ladies of the Aventine, or secretaries so eager and ready to help, so proud to be associated with it. He was at the same time within reach of Bishop Damasus, a man of many experiences, who seems to have loved him as a son, and who not only made him his secretary, but his private counsellor in many difficulties and dangers: and Jerome soon became the centre also of a little band of chosen friends, distinguished personages in Roman society connected in faith and in blood with the sisterhood, whom he speaks of as Daniel, Ananias, Azarias, and Misael, some of whom were his own old companions and schoolfellows, all deeply attached to him and proud of his friendship. No more delightful position could have been imagined for the repose and strengthening of a man who had endured many hardships, and who had yet before him much more to bear.

Jerome remained nearly three years in this happy retreat, and it was here that he executed the first portion of his great work, that first authoritative translation of the entire Canon of Scripture which still retains its place in the Church of Rome—the Vulgate, so named when the Latin of Jerome, which is by no means that of Cicero, was the language of the crowd. In every generation what is called the higher education of women is treated as a new and surprising thing by the age, as if it were the greatest novelty; but we doubt whether Girton itself could produce graduates as capable as Paula and Marcella of helping in this work, discussing the turning of a phrase or the meaning of an abstruse Hebrew word, and often holding their own opinion against that of the learned writer whose scribes they were so willing to be. This undertaking gave a double charm to the life, which went on with much variety and animation, with news from all quarters, with the constant excitement of a new charity established, a new community founded: and never without amusement either, much knowledge of the sayings and doings of society outside, visits from the finest persons, and a daily entertainment in the flutterings of young Blæsilla between the world and the convent, and her pretty ways, so true a woman of the world, yet all the same a predestined saint: and the doings of Fabiola, one day wholly absorbed in the foundation of her great hospital, the first in Rome, the next not so sure in her mind that love, even by means of a second divorce, might not win the day over devotion. Even Paula in these days was but half decided, and came, a dazzling vision in her jewels and her crown, to visit her friends, in all the pomp of autumnal beauty, among her daughters, of whom that serious little maiden Eustochium was the only one quite detached from the world. For was there not also going on under their eyes the gentle wooing of Pammachius and Paulina to make it apparent to the world that the ladies on the Aventine did not wholly discredit the ordinary ties of life, although they considered with St. Paul that the other was the better way? The lovers were as devout and as much given up to good works as any of them, yet, as even Jerome might pardon once in a way, preferred to the cloister the common happiness of life. These good works were the most wonderful part of all, for every member of the community was rich. Their fortunes were like the widow's cruse. One hears of great foundations like that of Fabiola's hospital and Melania's provision for the monks in Africa, for which everything was sacrificed; yet, next day, next year, renewed beneficences were forthcoming, and always a faithful intendant, a good steward, to continue the bountiful supplies. So wonderful indeed are these liberalities, and so extraordinary the details, that it is surprising to find that no learned German, or other savant, has, as yet, attempted to prove that the fierce and vivid Jerome never existed, that his letters were the work of half a dozen hands, and the subjects of his brilliant narrative altogether fictitious—Melania and Paula being but mythical repetitions of the same incident, wrapt in the colours of fable. This hypothesis might be made to seem very possible if it were not, perhaps, a little too late in the centuries for the operations of that high-handed criticism, and Jerome himself a very hard fact to encounter.

But the great wealth of these ladies remains one of the most singular circumstances in the story. When they sell and sacrifice everything it is clear it must only be their floating possessions, leaving untouched the capital, as we should say, or the estates, perhaps, more justly, the wealthy source from which the continued stream flowed. This gave a splendour and a largeness of living to the home on the Aventine. There was no need to send any petitioner away empty, charity being the rule of life, and no thought having as yet entered the most elevated mind that to give to the poor was inexpedient for them, and apt to establish a pauper class, dependent and willing to be so. These ladies filled with an even and open hand every wallet and every mouth. They received orphans, they provided for widows, they filled the poor quarters below the hill—where all the working people about the Marmorata clustered near the river bank, in the garrets and courtyards of the old houses—with asylums and places of refuge. The miserable and idle populace of which the historian speaks so contemptuously, the fellows who hung about the circuses, and had no name but the nicknames of coarsest slang, the Cabbage-feeders, the Sausage-eaters, &c., the Porringers and Gluttons, were, no doubt, left all the more free to follow their own foul devices; but the poor women, who though perhaps far from blameless suffer most in the debasement of the population, and the unhappy little swarms of children, profited by this universal balm of charity, and let us hope grew up to something a little better than their sires. For however paganism might linger among the higher class, the multitudes were all nominally Christian. It was to the tombs of the Apostles that they made their pilgrimages, rather than to the four hundred temples of the gods. "For all its gilding the Capitol looks dingy," says Jerome himself in one of his letters; "every temple in Rome is covered with soot and cobwebs, and the people pour past those half-ruined shrines to visit the tombs of the apostles."

The house of Marcella was in the condition we have attempted to describe when Jerome became its guest. It was in no way more rigid in its laws than at the beginning. The little ecclesia domestica, as he happily called it, seems to have been entirely without rule or conventual order. They sang psalms together (sometimes we are led to believe, in the original Hebrew learned for the purpose—but it must have been few who attained to this height), they read together, they held their little conferences on points of doctrine, with much consultation of learned texts; but there is no mention even of any regular religious service, much less of matins, and vespers, and nones and compline, and the other ritualistic divisions of a monastic day; for indeed no rule had been as yet invented for any cœnobites of the West. We do not hear even of a daily mass. Often there were desertions from the ranks, sometimes a young maiden withdrawing from the social enclosure, sometimes a young widow drawn back into the vortex of the fashionable world. But on the whole the record of the little domestic church, with its bodyguard of faithful friends and servitors outside, and Jerome, its pride and crown of glory, within, is one of serene and happy life, dignified by everything that was best in the antique world.

It was after the arrival of Jerome that the little tragedy of Blæsilla, the eldest daughter of Paula, occurred, rending their gentle hearts. "Our dear widow," as Jerome called her, had no idea of second marriage in her mind. The first, it would appear, had not been happy; and Blæsilla, fair and rich and young, had every mind to enjoy her freedom, her fine dresses, and all the pleasures of her youth. Safely lodged under her mother's wing, with those irreproachable friends 011 the Aventine about her, no gossip touched her gentle name. The community amused itself with her light-hearted ways. "Our widow loves to adorn herself. She is the whole day before her mirror," says Jerome, and there is no harsh tone in his voice. But in the midst of her gay and innocent life she fell ill of a fever, no unusual thing. It lingered, however, more than a month and took a dangerous form, so that the doctors began to despair. When things were at this point Blæsilla had a dream or vision, in her fever, in which the Saviour appeared to her and bade her arise as He had done to Lazarus. It was the crisis of the disease, and she immediately began to recover, with the deepest faith that she had been cured by a miracle. The butterfly was touched beyond measure by this divine interposition, as she believed, in her favour, and as soon as she was well, made up her mind to devote herself to God. "An extraordinary thing has happened," cries Jerome. "Blæsilla has put on a brown gown! What a scandal is this!" He launches forth thereupon into a diatribe upon the fashionable ladies, with faces of gypsum like idols, who dare not shed a tear lest they should spoil their painted cheeks, and who are the true scandal to Christianity: then narrates with growing tenderness the change that has taken place in the habits of the young penitent. She, whose innocent head was tortured with curls and plaits and crowned with the fashionable mitella, now finds a veil enough for her. She lies on the ground who found the softest cushions hard, and is up the first in the morning to sing Alleluia in her silvery voice.

The conversion rang through Rome all the more that Blæsilla was known to have had no inclination toward austerity of life. Her relations, half pagan and altogether worldly, were hot against the fanatic monk, who according to the usual belief tyrannised over the whole house in which he had been so kindly received, and the weak-minded mother who had lent herself to his machinations. The question fired Rome, and became a matter of discussion under every portico and wherever men or women assembled. Was it lawful, had it any warrant in law or history, this new folly of opposing marriage and representing celibacy as a happier and holier state? It was against every tradition of the race; it tore families in pieces, abstracted from society its most brilliant members, alienated the patrimony of families, interfered with succession and every natural law. In the turmoil raised by this event, a noisy public controversy arose. Two assailants presented themselves, one a priest, who had been for a time a monk, and one a layman, to maintain the popular canon, the superiority of marriage and the natural life of the world. These arguments had a great effect upon the public mind, naturally prone to take fright at any interference with its natural laws. They had very serious results at a later period both in the life of Paula and that of Jerome, and they seem to have threatened for a time serious injury to the newly established convents which Marcella's community had planted everywhere, and from which half-hearted sisters took this opportunity of separating themselves. It is amusing to find that, by a curious and furious twist of the usual argument, Jerome in his indignant and not always temperate defence describes these deserters as old and ugly, and unable to find husbands notwithstanding the most desperate efforts. It has been very common to allege this as a reason for the self-dedication of nuns: and it is always a handy missile to throw.

Jerome was not the man to let any such fine opening for a controversy pass. He burst forth upon his opponents, thundering from the heights of the Aventine, reducing the feeble writers who opposed him to powder. Helvidius, the layman above mentioned, had taken up the question—a question always offensive and injurious to natural sentiment and prejudice, exclusive even of religious feeling, a