CHAPTER V.

PAULA.

Paula was a woman of very different character from the passionate and austere Melania who preceded and resembled her in many details of her career. Full of tender and yet sprightly humour, of love and gentleness and human kindness, a true mother benign and gracious, yet with those individualities of lively intelligence, understanding, and sympathy which quicken that mild ideal and bring in all the elements of friendship and the social life—she was the most important of those visitors and associates who made the House on the Aventine the fashion, and filled it with all that was best in Rome. Though her pedigree seems a little delusive, her relationship to Æmilius Paulus resolving itself into a descent from his sister through her own mother, it is yet apparent that her claims of the highest birth and position were fully acknowledged, and that no Roman matron held a higher or more honourable place. She was rich as they all were, highly allied, the favourite of society, neglecting none of its laws, though always with a love of intellectual intercourse and a tendency to devotion. Which of these tendencies drew her first towards Marcella and her little society we cannot tell: but it is evident that both found satisfaction there, and were quickened by the strong impulse given by Jerome when he came out of the schools and out of the wilds, at once Scholar and Hermit, to this house of friendship, the Ecclesia Domestica of Rome. That all this rising tide of life, the books, the literary work, the ever-entertaining companionship, as well as the higher influence of a life of self-denial and renunciation, as understood in those days—should have at first added a charm even to that existence upon its border, the life in which every motive contradicted the new law, is very apparent. Many a great lady, deeply plunged in all the business of the world, has felt the same attraction, the intense pleasure of an escape from those gay commotions which in the light of the other life seem so insignificant and wearisome, the sensation of rest and tranquillity and something higher, purer, in the air—which yet perhaps at first gave a zest to the return into the world, in itself once more a relief from that higher tension and those deeper requirements. The process by which the attraction grew is very comprehensible also. Common pleasures and inane talk of society grow duller and duller in comparison with the conversation full of wonders and revelations which would keep every faculty in exercise, the mutual studies, the awe yet exhilaration of mutual prayers and psalms, the realisation of spiritual things. And no doubt the devout child's soul so early fixed, the little daughter who had thought of nothing from her cradle but the service of God, must have drawn the ever-tender, ever-sympathetic mother still nearer to the centre of all. The beautiful mother among her girls, one betrothed, one self-consecrated, one in all the gay emancipation of an early widowhood, affords the most charming picture among the graver women—women all so near to each other in nature,—mutually related, members of one community, linked by every bond of common association and tradition.

When Blæsilla on her recovery from her illness threw off her gaieties and finery, put on the brown gown, and adopted all the rules of the community, the life of Paula, trembling between two spheres, was shaken by a stronger impulse than ever before. But how difficult was any decision in her circumstances! She had her boy and girl at home as yet undeveloped—her only boy, dragged as much as might be to the other side, persuaded to think his mother a fanatic and his sisters fools. Paula did all she could to combine the two lives, indulging perhaps in an excess of austerities under the cloth of gold and jewels which, as symbols of her state and rank, she could not yet put off. The death of Blæsilla was the shock which shattered her life to pieces. Even the coarse reproaches of the streets show us with what anguish of mourning this first breach in her family overwhelmed her. "This is why she weeps for her child as no woman has ever wept before," the crowd cried, turning her sorrow into an accusation, as if she had thus acknowledged her own fault in leaving Blæsilla to privations she was not able to endure. Did the cruel censure perhaps awake an echo in her heart, ready as all hearts are in that moment of prostration to blame themselves for something neglected, something done amiss? At least it would remind Paula that she herself had never made completely this sacrifice which her child had made with such fatal effect. She was altogether overcome by her sorrow: her sobs and cries rent the hearts of her friends. She refused all food, and when exhausted by the paroxysms of violent grief fell into a lethargy of despair more alarming still. When every one else had tried their best to draw her from this excess of affliction, the ladies had recourse to Jerome in their extremity: for it was clear that Paula must be roused from this collapse of all courage and hope, or she must die.

Jerome did not refuse to answer the appeal: though helpless as even the most anxious affection is in face of this anguish of the mother which will not be comforted, he did what he could; he wrote to her from the house of their friends who shared yet could not still her sorrow, a letter full of grief and sympathy, in the forlorn hope of bringing her back to life. Such letters heaven knows are common enough. We have all written, and most of us have received them, and found in their tender arguments, in their assurances of final good and present fellow feeling, only fresh pangs and additional sickness of heart. Yet Jerome's letter was not of a common kind. No one could have touched the shrinking heart with a softer touch than this fierce controversialist, this fiery and remorseless champion: for he had yet a more effectual spell to move the mourner, in that he was himself a mourner, not much less deeply touched than she. "Who am I," he cries, "to forbid the tears of a mother who myself weep? This letter is written in tears. He is not the best consoler whom his own groans master, whose being is un-manned, whose broken words distil into tears. Yes, Paula, I call to witness Christ Jesus whom our Blæsilla now follows, and the angels who are now her companions, I, too, her father in the spirit, her foster-father in affection, could also say with you—Cursed be the day that I was born. Great waves of doubt surge over my soul as over yours. I, too, ask myself why so many old men live on, why the impious, the murderers, the sacrilegious, live and thrive before our eyes, while blooming youth and childhood without sin are cut off in their flower." It is not till after he has thus wept with her that he takes a severer tone. "You deny yourself food, not from desire of fasting, but of sorrow. If you believed your daughter to be alive, you would not thus mourn that she has migrated to a better world. Have you no fear lest the Saviour should say to you, 'Are you angry, Paula, that your daughter has become my daughter? Are you vexed at my decree, and do you with rebellious tears grudge me the possession of Blæsilla?' At the sound of your cries Jesus, all-clement, asks, 'Why do you weep? the damsel is not dead but sleepeth.' And when you stretch yourself despairing on the grave of your child, the angel who is there asks sternly, 'Why seek ye the living among the dead?'"

In conclusion Jerome adds a wonderful vow: "So long as breath animates my body, so long as I continue in life, I engage, declare and promise that Blæsilla's name shall be for ever on my tongue, that my labours shall be dedicated to her honour, and my talents devoted to her praise." It was the last word which the enthusiasm of tenderness could say: and no doubt the fervour and warmth of the promise, better kept than such promises usually are, gave a little comfort to the sorrowful soul.

When Paula came back to the charities and devotions of life after this terrible pause a bond of new friendship was formed between her and Jerome. They had wept together, they bore the reproach together, if perhaps their trembling hearts might feel there was any truth in it, of having possibly exposed the young creature they had lost to privations more than she could bear. But it is little likely that this modern refinement of feeling affected these devoted souls; for such privations were in their eyes the highest privileges of life, and in fasting man was promoted to eat the food of angels. At all events, the death of Blæsilla made a new bond between them, the bond of a mutual and most dear remembrance never to be forgotten.

This natural consequence of a common sorrow inflamed the popular rage against Jerome to the wildest fury. Paula's relations and connections, half of them, as in most cases in the higher ranks of society, still pagan—who now saw before them the almost certain alienation to charitable and religious purposes of Paula's wealth, pursued him with calumny and outrage, and did not hesitate to accuse the lady and the monk of a shameful relationship and every crime. To make things worse, Damasus, whose friend and secretary, almost his son, Jerome had been, died a few months after Blæsilla, depriving him at once of that high place to which the Pope's favour naturally elevated him. He complains of the difference which his close connection with Paula's family had made on the general opinion of him. "All, almost without exception, thought me worthy of the highest sacerdotal position; there was but one word for me in the world. By the mouth of the blessed Damasus it was I who spoke. Men called me holy, humble, eloquent." But all this had changed since the recent events in Paula's house. She on her side, wounded to the heart by the reproaches poured upon her, and the shameful slanders of which she was the object, and which had no doubt stung her into renewed life and energy, resolved upon a step stronger than that of joining the community, and announced her intention of leaving Rome, seeking a refuge in the holy city of Jerusalem, and shaking the dust of her native country, where she had been so vilified, from her feet. This resolution was put to Jerome's account as might have been expected, and when his patron's death left him without protection every enemy he had ever made, and no doubt they were many, was let loose. He whom courtiers had sought, whose hands had been kissed and his favour implored by all who sought anything from the Pope, was now greeted when he appeared in the streets by fierce cries of "Greek," "Impostor," "Monk," and his presence became a danger for the peaceful house in which he had found a refuge.

It is scarcely possible to be very sorry for Jerome. He had not minced his words; he had flung libels and satires about that must have stung and wounded many, and in such matters reprisals are inevitable. But Paula had done no harm. Even granting the case that Blæsilla's health had been ruined by fasting, the mother herself had gone through the same privations and exulted in them: and her only fault was to have followed and sympathised in, with enthusiasm, the new teaching and precepts of the divine life in the form which was most highly esteemed in her time. No cry from that silent woman comes into the old world, ringing with so many outcries, where the rude Roman crowd bellowed forth abuse, and the ladies on their silken couches whispered the scandal of Paula's liaison to each other, and the men scoffed and sneered over their banquets at the mere thought of such a friendship being innocent. Some one of their enemies ventured to speak or write publicly the vile accusation, and was instantly brought to book by Jerome, and publicly forswore the scandal he had spread. "But," as Jerome says, "a lie is hard to kill; the world loves to believe an evil story: it puts its faith in the lie, but not in the recantation." And the situation of affairs became such that he too saw no expedient possible but that of leaving Rome. He would seem to have been, or to have imagined himself, in danger of his life, and his presence was unquestionably a danger for his friends. A man of more patient temperament and quiet mind might have thought that Paula's resolution to go away was a reason for him to stay, and thus to bear the scandal and outrage alone, at least until she was safe out of its reach—giving no possible occasion for the adversary to blaspheme. But Jerome was evidently not disposed to any such self-abnegation, and indeed it is very likely that his position had become intolerable and that his only resource was departure. It was in the summer of 385, nearly three years after his arrival in Rome—in August, seven months after the death of Damasus, and not a year after that of Blæsilla, that he left "Babylon," as he called the tumultuous city, writing his farewell with tears of grief and wrath to the Lady Asella, now one of the eldest and most important members of the community, and thanking God that he was found worthy of the hatred of the world. We are apt to speak as if travelling were an invention of our time: but as a matter of fact facilities of travelling then existed little inferior to those we ourselves possessed thirty or forty years ago, and it was no strange or unusual journey from Ostia at the mouth of the Tiber, by the soft Mediterranean shores, past the vexed rocks of the Sirens in the blazing weather, to Cyprus that island of monasteries, and Antioch a vexed and heresy-tainted city yet full of friends and succour. Jerome had a cluster of faithful followers round him, and was escorted by a weeping crowd to the very point of his embarkation: but yet swept forth from Rome in a passion of indignation and distress.

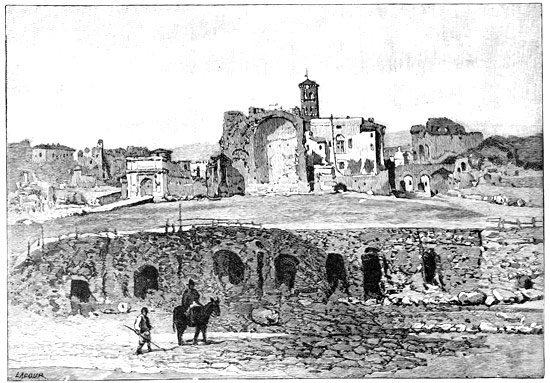

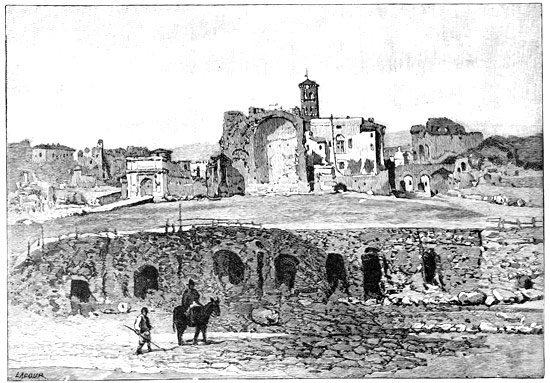

TEMPLE OF VENUS AND ROME FROM THE COLOSSEUM (1860).

To face page 72.

It was while waiting for the moment of departure in the ship that was to carry him far from his friends and the life he loved, that Jerome's letters to Asella were written. They were full of anger and sorrow, the utterance of a heart sore and wounded, of a man driven almost to despair. "I am said," he cries, "to be an infamous person, a deceiver full of guile, an impostor with all the arts of Satan at his fingers' ends.... These men have kissed my hands in public, and stung me in secret with a viper's tooth; they compassionate me with their lips and rejoice in their hearts. But the Lord saw them, and had them in derision, reserving them to appear with me, his unfortunate servant, at the last judgment. One of them ridicules my walk, and my laugh: another makes of my features a subject of accusation: to another the simplicity of my manners is the evil thing: and I have lived three years in the company of such men!" He continues his indignant self-defence as follows:

"I have lived surrounded by virgins, and to some of them I explained as best I could the divine books. With study came an increased knowledge of each other, and with that knowledge mutual confidence. Let them say if they have ever found anything in my conduct unbecoming a Christian. Have I not refused all presents, great or small? Gold has never sounded in my palm. Have they heard from my lips any doubtful word, or seen in my eyes a bold or hazardous look? Never, and no one dares say so. The only objection to me is that I am a man: and that objection only appeared when Paula announced her intention of going to Jerusalem. They believed my accuser when he lied: why do they not believe him when he retracts? He is the same man now as then. He imputed false crimes to me, now he declares me innocent. What a man confesses under torture is more likely to be true than that which he gives forth in a moment of gaiety: but people are more prone to believe such a lie than the truth.

"Of all the ladies in Rome Paula only, in her mourning and fasting, has touched my heart. Her songs were psalms, her conversations were of the Gospel, her delight was in purity, her life a long fast. But when I began to revere, respect, and venerate her, as her conspicuous virtue deserved, all my good qualities forsook me on the spot.

"Had Paula and Melania rushed to the baths, taken advantage of their wealth and position to join, perfumed and adorned, in one worship God and their wealth, their freedom and pleasure, they would have been known as great and saintly ladies; but now it is said they seek to be admired in sackcloth and ashes, and go down to hell laden with fasting and mortifications: as if they could not as well have been damned along with the rest, amid the applauses of the crowd. If it were Pagans and Jews who condemned them, they would have had the consolation of being hated by those who hated Christ, but these are Christians, or men known by that name.

"Lady Asella, I write these lines in haste, while the ship spreads its sails. I write them with sobs and tears, yet giving thanks to God to have been found worthy of the hatred of the world. Salute Paula and Eustochium, mine in Christ whether the world pleases or not, salute Albina your mother, Marcella your sister, Marcellina, Felicita: say to them that we shall meet again before the judgment seat of God, where the secrets of all hearts shall be revealed. Remember me, oh example of purity! and may thy prayers tranquillise before me the tumults of the sea!"

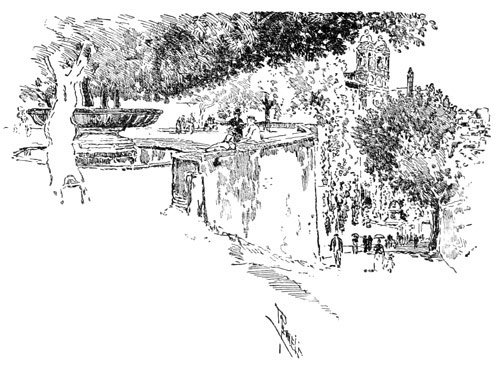

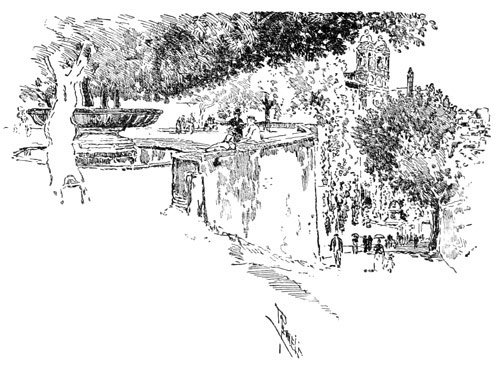

TRINITA DE' MONTI.

The agitation with which the community of ladies must have received such a letter may easily be imagined. They were better able than any others to judge of the probity and honour of the writer who had lived among them so long: and no doubt all these storms raging about, the injurious and insulting imputations, all the evil tongues of Rome let loose upon the harmless house, their privacy invaded, their quiet disturbed, must, during the whole course of the deplorable incident, have been the cause of pain and trouble unspeakable to the gentle society on the Aventine. Marcella it is evident had done what she could to stop the mouth of Jerome when the trouble began; it is perhaps for this reason that the letter of farewell is addressed to the older Asella, perhaps a milder judge.

Paula's preparations had begun before Jerome had as yet thought of his more abrupt departure. They were not so easily made as those of a solitary already detached from the world. She had all her family affairs to regulate, and, what was harder still, her children to part with, the most difficult of all, and the special point in her conduct with which it is impossible for us to sympathise. But it must be remembered that Paula, a spotless matron, had been branded with the most shameful of slanders, that she had been shrieked at by the crowd as the slayer of her daughter, and accused by society of having dishonoured her name. She had been the subject of a case of libel, as we should say, before the public courts, and though the slanderer had confessed his falsehood (under the influence of torture it would seem, according to the words of Jerome), the imputation, as in most cases, remained. Outraged and wounded to the quick, it is very possible that she may have thought that it was well for her younger children that she should leave them, that they might not remain under the wing of a mother whose name had been bandied about in the mouths of men. Her daughter Paulina was by this time married to the good and faithful Pammachius, whose protection might be of greater advantage to the younger girl and boy than her own. And Paula had full knowledge of the tender mercies of her pagan relations, and of the influence they were likely to exercise against her, even in her own house. The staid young Eustochium, grave and calm, clung to her mother's side, her youthful head already covered by the veil of the dedicated virgin, a serene and unfaltering figure in the midst of all the agitations of the parting. All Rome poured forth to accompany them to the port, brothers and sisters with their wives and husbands, relations less near, a crowd of friends. All the way along the winding banks of the Tiber they plied Paula with entreaties and reproaches and tears. She made them no reply. She was at all times slow to speak, as the tender chronicle reports. "She raised her eyes to heaven, pious towards her children but more pious to God." She retained her self-command until the vessel began to move from the shore, where little Toxotius, the boy of ten years old, stood stretching out his hands to her in a last appeal, his sister Rufina silent, with wistful eyes, by his side. Paula's heart was like to burst. She turned her eyes away unable to bear that cruel sight, while Eustochium, firm and steadfast, supported her weaker mother in her arms.

Was it a cruel desertion, a heartless abandonment of duty? Who can tell? There are desertions, cruelties in this kind, which are the highest sacrifice, and sometimes the most bitter proof of self-devotion. Did Paula in her heart believe, most painful thought that can enter a mother's mind, that her boy would be better without her, brought up in peace among his uncles and guardians, who, had she been there, would have made his life a continual struggle between two sides? Was Rufina more likely to be happy in her gentle sister's charge, than with her mind disturbed, and perhaps her marriage spoiled, by her mother's religious vows, and all that was involved in them? She might be wrong in thinking so, as we are all wrong often in our best and most painfully pondered plans. But condemnation is very easy, and gives so little trouble—there is surely a word to be said on the other side of the question.

When these pilgrims leave Rome they cease to have any part in the story of the great city with which we have to do. Yet their after-fate may be stated in a few words. No need to follow the great lady in her journey over land and sea to the Holy Land with all its associations, where Jerusalem out of her ruins, decked with a new classic name, was already rising again into the knowledge and the veneration of the world. These were not the days of excursion trains and steamers, it is true; but the number of pilgrims ever coming and going to those more than classic shores, those holy places, animated with every higher hope, was perhaps greater in proportion to the smaller size and less population of the known world than are our many pilgrimages now, though this seems so strange a thing to say. But is there not a Murray, a Baedeker, of the fourth century, still existent, the Itinéraire de Bordeaux à Jerusalem, unquestioned and authentic, containing the most careful account of inns and places of refuge and modes of travel for the pilgrims? It is possible that the lady Paula may have had that ancient roll in her satchel, or slung about the shoulders of her attendant for constant reference. Her ship was occupied by her own party alone, and conveyed, no doubt, much baggage and many provisions as an emigration for life would naturally do; and it was hindered by no storms, as far as we hear, but only by a great calm which delayed the vessel much and made the voyage tedious, necessitating the use of the galley's oars, which very likely the ladies would like best, though it kept them so many more days upon the sea. They reached Cyprus at last, that holy island now covered with monasteries, where Epiphanius, once Paula's guest in Rome, awaited and received her with every honour, and where there were many visits to be paid to monks and nuns in their new establishments, the favourite dissipation of the cloister. The ladies afterwards continued their voyage to Antioch, where they met Jerome; and proceeded on their journey, having probably had enough of the sea, along the coast by Tyre and Sidon, by Herod's splendid city of Cæsarea, and Joppa with its memories of the Apostles—not without a thought of Andromeda and her monster as they looked over the dark and dangerous reefs which still scare the traveller: for they loved literature, notwithstanding their separation from the world. They formed by this time a great caravanserai, not unlike, to tell the truth, one of those parties which we are so apt to despise, under charge of guides and attendants who wear the livery of Cook. But such an expedition was far more dignified and important in those distant days. Jerome and his monks made but one family of sisters and brothers with the Roman ladies and their followers, who endured so bravely all the fatigues and dangers of the way. Paula the pilgrim was no longer a tottering fine lady, but the most animated and interested of travellers, with no mere mission of hermit-hunting like Melania, but the truest human enthusiasm for all the storied scenes through which she passed. When they reached Jerusalem she went in a rapture of tears and exaltation from one to another of the sacred sites, kissing the broken stone which was supposed to have been that which was rolled against the door of the Holy Sepulchre, and following with pious awe and joy the steps of Helena into the cave where the True Cross was found. The legend was still fresh in those days, and doubts there were none. The enthusiasm of Paula, the rapture and exaltation, which found vent in torrents of tears, in ecstasies of sacred emotion, joy and prayer, moved all the city, thronged with pilgrims, devout and otherwise, to whom the great Roman lady was a wonder: the crowd followed her about from point to point, marvelling at her devotion and the warmth of natural feeling which in all circumstances distinguished her. The reader cannot but follow still with admiring interest a figure so fresh, so unconventional, so profoundly touched by all those holy and sacred associations. Amid so many who are represented as almost more abstracted among spiritual thoughts than nature permits, her frank emotion and tender, natural enthusiasm are always a refreshment and a charm.

We come here upon a break in the hitherto redundant story. Melania and Rufinus were in possession of their convents, and fully established as residents on the Mount of Olives, when the other pilgrims arrived; and there can be but little doubt that every grace of hospitality was extended by the one Roman lady to the other, as well as by the old companions of Jerome to her friend. But in the course of the after-years these dear friends quarrelled bitterly, not on personal matters, so far as appears, but on points of doctrine, and fell into such prolonged warfare of angry and stinging words as hurt more than blows. By means of this very intimacy they knew everything that had ever been said or whispered of each other, and in the heat of conflict did not hesitate to use every old insinuation, every suggestion that could hurt or wound. The struggle ran so high that the after-peace of both parties was seriously affected by it; and one of its most significant results was that Jerome, a man great enough and little enough for anything, either in the way of spitefulness or magnanimity, cut off from his letters and annals all mention of this early period of peace, and all reference to Melania, whom he is supposed to have praised so highly in his first state of mind that it became impossible in his second to permit these expressions of amity to be connected with her name. This is a melancholy explanation of the silence which falls over the first period of Paula's residence in Palestine, but it is a very natural one: and both sides were equally guilty. The quarrel happened, however, years after the first visit, which we have every reason to believe was all friendliness and peace.

After this first pause at Jerusalem, the caravanserai got under way again and set out on a long journey through all the scenes of the Old Testament, the storied deserts and ruins of Syria, not much less ancient to the view and much less articulate than now. This was in the year 387, two years after their departure from Rome. Even now, with all our increased facilities for travel—neutralised as they are by the fact that these wild and desert lands will probably never be adapted to modern methods—the journey would be a very long and fatiguing business. Jerome and his party "went everywhere," as we should say; they were daunted by no difficulties. No modern lady in deer-stalker's costume could have shrunk less from any dangerous road than the once fastidious Paula. They stopped everywhere, receiving the ready hospitality of the convents in every awful pass of the rocks and stony waste where such homes of penance were planted. Those wildernesses of ruin, from which our own explorers have picked carefully out some tradition of Gilgal or of Ziklag, some Philistine stronghold or Jewish city of refuge—were surveyed by these adventurers fourteen hundred years ago, when perhaps there was greater freshness of tradition, but none of the aids of science to decipher what would seem even more hoary with age to them than it does to us. How trifling in our pretences at exploration do the luxurious parties of the nineteenth century seem, abstracted from common life for a few months at the most, and with all the resources of civilisation to fall back upon, in comparison with that of these patient wanderers, eating the Arab bread and clotted milk, and such fare as was to be got at, finding shelter among the dark-skinned ascetics of the desert communities, taking refuge in the cave which some saint but a day or two before had inhabited, wandering everywhere, over primeval ruin and recent shrine!

When they came back from these savage wildernesses to green Bethlehem standing up on its hillside over the pleasant fields, the calm and sweetness of the place went to their hearts. It was in this sacred spot that they decided to settle themselves, building their two convents, Jerome's upon the hill near the western gate, Paula's upon the smiling level below. He is said to have sold all that he had, some remains of personal property in Dalmatia belonging to himself and his brother, who was his faithful and constant companion, to provide for the expenses of the building, on his side; and no doubt the abundant wealth of Paula supplemented all that was wanting. Gradually a conventual settlement, such as was the ideal of the time, gathered in this spot. After her own convent was finished Paula built two others near it, which were soon filled with dedicated sisters. And she built a hospice for the reception of travellers, so that, as she said with tender smiles and tears, "If Joseph and Mary should return to Bethlehem, they might be sure of finding room for them in the inn." This soft speech shines like a gleam of tender light upon the little holy city with all its memories, showing us the great lady of old in her gracious kindness, full of noble natural kindness, and seeing in every poor pilgrim who passed that way some semblance of that simple pair, who carried the Light of the World to David's little town among the hills.

All these homes of piety and charity are swept away, and no tradition even of their site is left; but there is one storied chamber that remains full of the warmest interest of all. It is the rocky room, in one of the half caves, half excavations close to that of the Nativity, and communicating with it by rudely hewn stairs and passages, in which Jerome established himself while his convent was building, which he called his Paradise, and which is for ever associated with the great work completed there. All other traditions and memories grow dim in the presence of the great and sacred interest of the place. Yet it will be impossible even there for the spectator who knows their story to stand unmoved in the scene, practically unaltered since their day, where Jerome laboured