CHAPTER VI.

THE MOTHER HOUSE.

Amid all these changes the house on the Aventine—the mother house as it would be called in modern parlance—went on in busy quiet, no longer visible in that fierce light which beats upon the path of such a man as Jerome, doing its quiet work steadily, having a hand in many things, most of them beneficent, which went on in Rome. Albina the mother of Marcella, and Asella her elder sister, died in peace: and younger souls, with more stirring episodes of life, disturbed and enlivened the peace of the cloister, which yet was no cloister but open to all the influences of life, maintaining a large correspondence and much and varied intercourse with the society of the times. In the first fervour of the settlement in Bethlehem both Paula and Jerome (she by his hand) wrote to Marcella urging her to join them, to forsake the world in a manner more complete than she had yet done. "... You were the first to kindle the fire in us" (the letter is nominally from Paula and Eustochium): "the first by precept and example to urge us to adopt our present life. As a hen gathers her chickens, who fear the hawk and tremble at every shadow of a bird, so did you take us under your wing. And will you now let us fly about at random with no mother near us?"

This letter is full not only of affectionate entreaties but of delightful pictures of their own retired and peaceful life. "How shall I describe to you," the writer says, "the little cave of Christ, the hostel of Mary? Silence is more respectful than words, which are inadequate to speak its praise. There are no lines of noble colonnades, no walls decorated by the sweat of the poor and the labour of convicts, no gilded roofs to intercept the sky. Behold in this poor crevice of the earth, in a fissure of the rock, the builder of the firmament was born." She goes on with touching eloquence to put forth every argument to move her friend.

Read the Apocalypse of St. John and see there what he says of the woman clothed in scarlet, on whose forehead is written blasphemy, and of her seven hills, and many waters, and the end of Babylon. "Come out of her, my people," the Lord says, "that ye be not partakers of her sins." There is indeed there a holy Church; there are the trophies of apostles and martyrs, the true confession of Christ, the faith preached by the apostles, and heathendom trampled under foot, and the name of Christian every day raising itself on high. But its ambition, its power, the greatness of the city, the need of seeing and being seen, of greeting and being greeted, of praising and detracting, hearing or talking, of seeing, even against one's will, all the crowds of the world—these things are alien to the monastic profession and they have spoiled Rome, they all oppose an insurmountable obstacle to the quiet of the true monk. People visit you: if you open your doors, farewell to silence: if you close them, you are proud and unfriendly. If you return their politeness, it is through proud portals, through a host of grumbling insolent lackeys. But in the cottage of Christ all is simple, all is rustic: except the Psalms, all is silence: no frivolous talk disturbs you, the ploughman sings Allelujah as he follows his plough, the reaper covered with sweat refreshes himself with chanting a psalm, and it is David who supplies with a song the vine dresser among his vineyards. These are the songs of the country, its ditties of love, played upon the shepherd's flute. Will the time never come when a breathless courier will bring us the good news, your Marcella has landed in Palestine? What a cry of joy among the choirs of the monks, among all the bands of the virgins! In our excitement we wait for no carriage but go on foot to meet you, to clasp your hand, to look upon your face. When will the day come when we shall enter together the birthplace of Christ: when, leaning over the divine sepulchre, we weep with a sister, a mother, when our lips touch together the sacred wood of the Cross: when on the Mount of Olives our hearts and souls rise together in the rising of our Lord? Would not you see Lazarus coming out of his tomb, bound in his shroud? and the waters of Jordan purified for the washing of the Lord? Then we shall hasten to the shepherds' folds, and pray at the tomb of David. Listen, it is the prophet Amos blowing his shepherd's horn from the height of his rock; we shall see the monuments of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, and the three famous women, and Samaria and Nazareth, the flower of Galilee, and Shiloh and Bethel and other holy places, accompanied by Christ, where churches rise everywhere like standards of the victories of Christ. And when we return to our cavern we will sing together always, and sometimes we shall weep; our hearts wounded with the arrow of the Lord, we will say one to another, "I have found Him whom my soul loveth; I will hold Him, and will not let Him go!"

Similar words upon the happiness of rural life and retirement Jerome had addressed to Marcella before. He had warned her of the danger of the tumultuous sea of life, and how the frail bark, beaten by the waves, ought to seek the shelter of the port before the last hurricane breaks. The image was even more true than he imagined; but it was not of the perils of Rome in the dreadful time of war and siege which was approaching that he spoke, but of the usual dangers of common life to the piety of the recluse. "The port which we offer you, it is the solitude of the fields," he says:

Brown bread, herbs watered by our own hands, and milk, the daintiest of the country, supply our rustic feasts. We have no fear of drowsiness in prayer or heaviness in our readings, on such fare. In summer we seek the shade of our trees; in autumn the mild weather and pure air invite us to rest on a bed of fallen leaves; in spring, when the fields are painted with flowers, we sing our psalms among the birds. When winter comes, with its chills and snows, the wood of the nearest forest supplies our fire. Let Rome keep her tumults, her cruel arena, her mad circus, her luxurious theatres; let the senate of matrons pay its daily visits. It is good for us to cleave to the Lord and to put all our hope in Him.

But Marcella turned a deaf ear to these entreaties. Perhaps she still loved the senate of matrons, the meetings of the Souls, the irruption of gentle visitors, the murmur of all the stories of Rome, and the delicate difficulties of marriage and re-marriage brought to her for advice and guidance. The allusions in both these letters point to such a conclusion, and there is no reason why it should not have been so. The Superior of a convent has in this fashion in much later days fulfilled more important uses than the gentle nun of the fields. At all events this lady remained in her home, her natural place, and continued to pour forth her bounty upon the poor of her native city: which many would agree was perhaps the better, though it certainly was not the safer, way. The death of her mother, which made a change in her life, and might have justified a still greater breaking up of all old customs and ties, was perhaps the occasion of these affectionate arguments; but Marcella would herself be no longer young and in a position much resembling that of a mother in her own person, the trusted friend of many in Rome, and their closest tie to a more spiritual and better life. The light of such a guest as Jerome, attracting all eyes to the house and bringing it within the records of literary history, that sole mode of saving the daily life of a household from oblivion—had indeed died away, leaving life perhaps a little flat and blank, certainly much less agitated and visible to the outer world than when he was pouring forth fire and flame upon every adversary from within the shelter of its peaceful walls. But no other change had happened in the circumstances under which Marcella opened her palace to a few consecrated sisters, and made it a general oratory and place of pious counsel and retreat for the ladies of Rome. The same devout readings, the same singing of psalms (sometimes in the original), the same life of mingled piety and intellectualism must have gone on as before: and other fine ladies perhaps not less interesting than Paula must have sought with their confessions and confidences the ear of the experienced woman, who as Paula says in respect to herself and her daughters, "first carried the sparkle of light to our hearts, and collected us like chickens under your wing." She was the same, "our gentle, our sweet Marcella, sweeter than honey," open to every charity and kindness: not refusing, it would seem, to visit as well as to be visited, and willing to "live the life" without forsaking any ordinary bonds or traditions of existence. There is less to tell of her for this reason, but not perhaps less to praise.

Marcella had her share no doubt in forming the minds of the two younger spirits, vowed from their cradle to the perfect life of virginhood, the second Paula, daughter of Toxotius and his Christian wife; and the younger Melania, daughter also of the son whom his mother had abandoned as an infant. It is a curious answer to the stern virtue which reproaches these two Roman ladies with the cruel desertion of their children, to find that both those children, grown men, permitted or encouraged the vocation of their daughters, and were proud of the saintly renown of the mothers who had left them to their fate. The consecrated daughters however leave only a faint trace as of two spotless catechumens in the story. Incidents of a more exciting character broke now and then the calm of life in the palace on the Aventine. M. Thierry in his life of Jerome gives us perhaps a sketch too entertaining of Fabiola, one of the ladies more or less associated with the house of Marcella, a constant visitor, a penitent by times, an enthusiast in charity, a woman bent on making, or so it seemed, the best of both worlds. She had made early what for want of a better expression we may call a love match, in which she had been bitterly disappointed. That a divorce should follow was both natural and lawful in the opinion of the time, and Fabiola had already formed a new attachment and made haste to marry again. But the second marriage was a disappointment even greater than the first, and this repeated failure seems to have confused and excited her mind to issues by no means clear at first, probably even to herself. She made in the distraction of her life a sudden and unannounced visit to Paula's convent at Bethlehem, where she was a welcome and delightful visitor, carrying with her all the personal news that cannot be put into writing, and the gracious ways of an accomplished woman of the world. She is supposed to have had a private object of her own under this visit of friendship, but the atmosphere and occupations of the place must have overawed Fabiola, and though her object was hidden in an artful web of fiction she was not bold enough to reveal it, either to the stern Jerome or the mild Paula. What she did was to make herself delightful to both in the little society upon which we have so many side-lights, and which doubtless, though so laborious and full of privations, was a very delightful society, none better, with such a man as Jerome, full of intellectual power, and human experience, at its head, and ladies of the highest breeding like Paula and her daughter to regulate its simple habits. We are told of one pretty scene where—amid the talk which no doubt ran upon the happiness of that peaceful life amid the pleasant fields where the favoured shepherds heard the angels' song—there suddenly rose the voice of the new-comer reciting with the most enchanting flattery a certain famous letter which Jerome long before had written to his friend Heliodorus and which had been read in all the convents and passed from hand to hand as a chef d'œuvre of literary beauty and sacred enthusiasm. Fabiola, quick and adroit and emotional, had learned it by heart, and Jerome would have been more than man had he not felt the charm of such flattery.

For a moment the susceptible Roman seems to have felt that she had attained the haven of peace after her disturbed and agitated life. Her hand was full and her heart generous: she spread her charities far and wide among poor pilgrims and poor residents with that undoubting liberality which considered almsgiving as one of the first of Christian duties. But whether the little busy society palled after a time, or whether it was the great scare of the rumour that the Huns were coming that frightened Fabiola, we cannot tell, nor precisely how long her stay was. Her coming and going were at least within the space of two years. She was not made to settle down to the revision of manuscripts like her friends, though she had dipped like them into Hebrew and had a pretty show of knowledge. She would seem to have evidenced this however more by curious and somewhat frivolous questions than by any assistance given in the work which was going on. Nothing could be more kind, more paternal, than Jerome to the little band of women round him. He complains, it is true, that Fabiola sometimes propounded problems and did not wait for an answer, and that occasionally he had to reply that he did not know, when she puzzled him with this rapid stream of inquiry. But it is evident also that he did his best sincerely to satisfy her curiosity as if it had been the sincerest thing in the world. For instance, she was seized with a desire to know the symbolical meaning of the costume of the high priest among the Jews: and to gratify this desire Jerome occupied a whole night in dictating to one of his scribes a little treatise on the subject, which probably the fine lady scarcely took time to read. Nothing can be more characteristic than the indications of this bright and charming visitor, throwing out reflections of all that was going on round her, so brilliant that they seemed better than the reality, fluttering upon the surface of their lives, bringing all under her spell.

There seems but little ground however for the supposition of M. Thierry that it was in the interest of Fabiola that Amandus, a priest in Rome, wrote a letter laying before Jerome a case of conscience, that of a woman who had divorced her husband and married again, and who now was troubled in her mind as to her duty; whether the second husband was wholly unlawful, and whether she could remain in full communion with the Church, having made this marriage? If she was the person referred to no one has been able to divulge what the question meant—whether she had a third marriage in her mind, or if a wholly unnecessary fit of compunction had seized her; for as a matter of fact she had never been subjected by the Church to any pains or penalties in consequence of her second marriage. Jerome however, as might have been expected of him, gave forth no uncertain sound in his reply. According to the Church, he said, there could be but one husband, the first. Whatever had been his unworthiness, to replace him by another was to live in sin. Whether it was this answer which decided her action, or whether she had been moved by the powerful fellowship of Bethlehem to renounce the more agitating course of worldly life, at least it is certain that Fabiola's career was changed from this time. Perhaps it was her desire to shake off the second husband which moved her. At all events on her return to Rome she announced to the bishop that she felt herself guilty of a great sin, and that she desired to make public penance for the same.

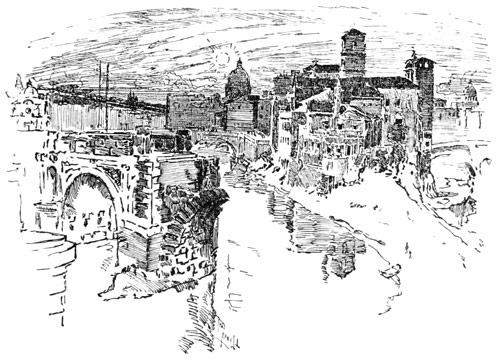

SAN BARTOLOMMEO.

Accordingly on the eve of Easter, when the penitents assembled under the porch of the great Church of St. John Lateran, amid all the wild and haggard figures appearing there, murderers and criminals of all kinds, the delicate Fabiola, with her hair hanging about her shoulders, ashes on her head and on the dark robe that covered her, her face pale with fasting and tears, stood among them, a sight for the world. Under many aspects had all Rome seen this daughter of the great Fabian race, in the splendour of her worldly espousals, and at all the great spectacles and entertainments of a city given up to display and amusement. Her jewels, her splendid dresses, her fine equipages, were well known. With what curiosity would all her old admirers, her rivals in splendour, those who had envied her luxury and high place, gather to see her now in her voluntary humiliation, descending to the level of the very lowest as she had hitherto been on the very highest apex of society! All Rome we are told was there, gazing, wondering, tracing her movements under the portico, among these unaccustomed companions. Perhaps there might be a supreme fantastic satisfaction to the penitent—with that craving for sensation which the exhaustion of all kinds of triumphs and pleasures brings—in thus stepping from one extreme to the other, a gratification in the thought that Rome which had worshipped her beauty and splendour was now gazing aghast at her bare feet and dishevelled hair. One can have no doubt of the sensation experienced by the Tota urbe spectante Romana. It was worth while frequenting religious ceremonies when such a sight was possible! Fabiola,—once with mincing steps, and gorgeous liveried servants on either hand, descending languidly the great marble steps from her palace to the gilded carriage in which she sank fatigued when that brief course was over, the mitella blazing with gold upon her head, her robe woven with all the tints of the rainbow into metallic splendour of gold and silver threads. And now to see her amid that crowd of ruffians from the Campagna, and unhappy women from the purlieus of the city, her splendid head uncovered, her thin hands crossed in the rough sleeves of the penitent's gown! It might be to some perhaps a salutary sight—moving other great ladies with heavier sins on their heads than Fabiola's to feel the prickings of remorse; though no doubt it is equally possible that they might think they saw through her, and the new form of self-exhibition which attracted all the world to gaze. We are not told whether Fabiola found refuge in the house on the Aventine with Marcella, who had lit the fire of Christian faith in her heart as well as in that of Paula: or whether she remained, like Marcella, in her own house, making it another centre of good works. But at all events her life from this moment was entirely given up to charity and spiritual things. Her kinsfolk and noble neighbours still more or less Pagan, were filled with fury and indignation and that sharp disgust at the loss of so much good money to the world, which had so much to do in embittering opposition: but the Christians were deeply impressed, the homage of such a great lady to the faith, and her recantation of her errors affecting many as a true martyrdom.

If it was really compunction for the sin of the second marriage which so moved her, her position would much resemble that of the fine fleur of French society as at present constituted, in its tremendous opposition to the law of divorce, now lawful in France of the nineteenth century as it was in Rome of the fourth—but resisted with a splendid bigotry of feeling, altogether independent of morality or even of reason, by all that is noblest in the country. Fabiola's divorce had been perfectly lawful and according to all the teaching and traditions of her time. The Church had as yet uplifted no voice against it. She had not been shut out from the society even of the most pious, or condemned to any penance or deprivation. Not even Jerome (till forced to give a categorical answer), nor that purest circle of devout women at Bethlehem, had refused her any privilege. Her action was unique and unprecedented as a protest against the existing law of the land, as well as universal custom and tradition. We are not informed whether it had any lasting effect, or formed a precedent for other women. No doubt it encouraged the formation of the laws against divorce which originated in the Church itself but have held through the intervening ages a doubtful sway, broken on every side by Papal dispensations, until now that they have settled down into a bond of iron on the consciences of the devout—chiefly the women, more specially still the gentlewomen—of Catholic Europe, where as in Fabiola's time they are once more against the law of the land.

The unworthy second husband we are informed had died even before Fabiola's public act of penitence; but no further movements towards the world, or the commoner ways of life reveal themselves in her future career. If she returned to life with the veiled head and bare feet of her penitence, or if she resumed, like Marcella, much of the ordinary traffic of society, we have no information. But she was the founder of the first public hospital in Rome, besides the usual monasteries, and built in concert with Pammachius a hospice at Ostia at the mouth of the Tiber, where strangers and travellers from all parts of the world were received, probably on the model of that hospice for pilgrims which Paula had established. And she was herself the foremost nurse in her own hospital, shrinking from no office of charity. The Church has always and in all circumstances encouraged such practical acts of self-devotion.

The ladies of the Aventine and all the friends of Jerome had been disturbed a little before by the arrival of a stranger in Rome, also a pretended friend of Jerome, and at first very willing to shelter himself under that title, Rufinus, who brought with him—after a moment of delusive amiability during which he had almost deceived the very elect themselves—a blast of those wild gales of polemical warfare which had been echoing for some time with sacrilegious force and inappropriateness from the Mount of Olives itself. The excitement which he raised in Rome in respect to the doctrines of Origen caused much commotion in the community, which lived as much by news of the Church and reports of all that was going on in theology as by the daily bread of their charities and kindness. It was to Marcella that Jerome wrote, when, reports having been made to him of all that had happened, he exploded, with the flaming bomb of his furious rhetoric, the fictitious statements of Rufinus, by which he was made to appear a supporter of Origen. Into that hot and fierce controversy we have no need to enter. No one can study the life of Jerome without becoming acquainted with this episode and finding out how much the wrath of a Father of the Church is like the rage of other men, if not more violent; but happily as Rome was not the birthplace of this fierce quarrel it is quite immaterial to our subject or story. It filled the house of Marcella with trouble and doubt for a time, with indignation afterwards when the facts of the controversy were better known; but interesting as it must have been to the eager theologians there, filling their halls with endless discussions and alarms, lest this new agitation should interfere with the repose of their friend, it is no longer interesting except to the student now. Rufinus was finally unmasked, and condemned by the Bishop of Rome, chiefly by the exertions of Marcella, whom Oceanus, coming hot from the scene of the controversy, and Paulinian the brother of Jerome, had instructed in his true character. Events were many at this moment in that little Christian society. The tumult of controversy thus excited and all the heat and passion it brought with it had scarcely blown aside, when the ears of the Roman world were made to tingle with the wonderful story of Fabiola, and the crowd flew to behold in the portico of the Lateran her strange appearance as a penitent; and the commotion of that event had scarcely subsided when another wonderful incident appears in the contemporary history filling the house with lamentation and woe.

The young Paulina, dear on all accounts to the ladies of the Aventine as her mother's daughter, and as her husband's wife (for Pammachius, the friend and schoolfellow of Jerome, was one of the fast friends and counsellors of the community), as well as for her own virtues, died in the flower of life and happiness, a rich and noble young matron exhibiting in her own home and amid the common duties of existence, all the noblest principles of the Christian faith. She had not chosen what these consecrated women considered as the better way: but in her own method, and amid a world lying in wickedness, had unfolded that white flower of a blameless life which even monks and nuns were thankful to acknowledge as capable of existing here and there in the midst of worldly splendours and occupations. She left no children behind her, so that her husband Pammachius was free of the anxieties and troubles, as well as of the joy and pride, of a family to regulate and provide for. His young wife left to him all her property on condition that it should be distributed among the poor, and when he had fulfilled this bequest the sorrowful husband himself retired from life, and entered a convent, in obedience to the strong impulse which swayed so many. Before this occurred however "all Rome" was roused by another great spectacle. The entire city was invited to the funeral of Paulina as if it had been to her marriage, though those who came were not the same wondering circles who crowded round the Lateran gate to see Fabiola in her humiliation. It was the poor of Rome who were called by sound of trumpet in every street, to assemble around the great Church of St. Peter, where were those tombs of the Apostles which every Christian visited as the most sacred of shrines, and where Paulina was laid forth upon her bier, the mistress of the feast. The custom was an old one, and chambers for these funeral repasts were attached to the great catacombs and all places of burial. The funeral feast of Paulina however meant more than ordinary celebrations of the kind, as the place in which it was held was more impressive and imposing than an ordinary sepulchre however splendid. She must have been carried through the streets in solemn procession, from the heights on which stood the palaces of her ancient race, across the bridge, and by the tomb of Hadrian to that great basilica where the Apostles lay, her husband and his friends following the bier: and in all likelihood Marcella and her train were also there, replacing the distant mother. St. Peter's it is unnecessary to say was not the St. Peter's we know; but it was even then a great basilica, with wide extending porticoes and squares, and lofty roof, though the building was scarcely quite detached from the rock out of which the back part of the cathedral had been hewn.

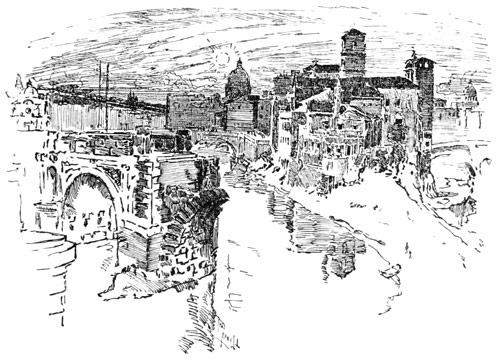

ST. PETER'S, FROM THE JANICULUM.

Many strange sights have been seen in that spot which once was the centre of the civilised world, and this which seems to us one of the strangest was in no way unusual or against the traditions of the age in which it occurred. The church itself, and all its surroundings, nave and aisles and porticoes, and the square beyond, were filled with tables, and to these from all the four quarters of Rome, from the circus and the benches of the Colosseum, where the wretched slept and lurked, from the sunny pavements, and all the dens and haunts of the poor by the side of the Tiber, the crowds poured, in those unconceivable yet picturesque rags which clothe the wretchedness of the South. They were ushered solemnly to their seats, the awe of the place, let us hope, quieting the voices of a profane and degraded populace, and overpowering the whispering, rustling, many-coloured multitude. Outside the later comers would be more unrestrained, and the roar, even though subdued, of thronging humanity must have come in strangely to the silence of the great church, and of the mourners, bent upon doing Paulina honour in this curious way. Did she lie there uplifted on her high bier to receive her guests? Or was the heart-broken Pammachius the host, standing pale upon the steps, over the grave of the Apostles? When they were "saturated" with food and wine, the first assembly left their places and were succeeded by another, each as he went away receiving from the hands of Pammachius himself a sum of money and a new garment. "Happy giver, unwearied distributor!" says the record. The livelong day this process went on; a winter day in Rome, not always warm, not always genial, very cold outside in the square under the evening breeze, and no doubt growing more and more noisy as one band continued to succeed another, and the first fed lingered about comparing their gifts, and hoping perhaps for some remnants to be collected at the end from the abundant and oft-renewed meal. There were no doubts in anybody's mind, as we have said, about encouraging pauperism or demoralising the recipients of these gifts; perhaps it would have been difficult to demoralise further that mendicant crowd. But one cannot help wondering how the peace was kept, whether there were soldiers or some manner of classical police about to keep order, or if the disgusted Senators would have to bestir themselves to prevent this wild Christian carnival of sorrow and charity from becoming a danger to the public peace.

We are told that it was the sale of Paulina's jewels, and her splendid toilettes which provided the cost of this extraordinary funeral feast. "The beautiful dresses woven with threads of gold were turned into warm robes of wool to cover the naked; the gems that adorned her neck and her hair filled the hungry with good things." Poor Paulina! She had worn her finery very modestly according to all reports; it had served no purposes of coquetry. The reader feels that something more congenial than that coarse and noisy crowd filling the church with its deformities and loathsomeness might have celebrated her burial. But not so was the feeling of the time; that they were more miserable than words could say, vile, noisome, and unclean, formed their claim of right to all these gifts—a claim from which their noisy and rude profanity, their hoarse blasphemy and ingratitude took nothing away. Charity was more robust in the early centuries than in our fastidious days. "If such had been all the feasts spread for thee by thy Senators," cried Bishop Paulinus, the historian of this episode, "oh Rome thou might'st have escaped the evils denounced against thee in the Apocalypse." We must remember that whatever might have been the opinion later, there was no doubt in any Christian mind in the fourth century that Rome was the Scarlet Woman of the Revelation of St. John, and that a dreadful fate was to overwhelm her luxury and pride.

Pammachius, when he had fulfilled the wishes of his wife in this way, thrilling the hearts of the mourning mother and sister in Bethlehem with sad gratification, and edifying the anxious spectators on the Aventine, carried out her will to its final end by becoming a monk, but with the curious mixture of devotion and independence common at the time, retired to no cloister, but lived in his own house, fulfilling his duties, and appearing even in the Senate in the gown and cowl so unlike the splendid garb of the day. He was no doubt one of the members for the poor in that august but scarcely active assembly, and occupied henceforward all his leisure in works of charity and religious organisations, in building religious houses, and protecting Christians in every necessity of life.

We have said that Rome in these days was as freely identified with the Scarlet Woman of the Apocalypse as ever was done by any Reformer or Puritan in later t