CHAPTER III

SOCIAL LIFE AMONG INDIAN TRIBES

Every boy is familiar with the arrangement of Boy Scouts, who name themselves the “Beavers,” “Lions,” “Bears,” or “Eagles”; and, strange to say, there is a similar practice among many savage peoples in America, Australia, and the Pacific region, though primitive tribes have many strange beliefs which we do not hear of among boys who take animals as their emblems.

One of the Déné tribes is divided into halves, the people of one division being “Bears,” while the others are all “Birds.” Now it is so ordered that a man or woman of the “Bear” division may not marry any one from his or her own half of the tribe; a person belonging to the “Bears” must always marry into the “Bird” clan, and an individual in the “Bird” division must select a partner from the “Bears.” The Indians cannot explain how this order originated; they say it always has been so and must remain. Some go so far as to declare that animals, who were their ancestors, ordered this tribal division, and laid down the rules for marriage. The missionary, Father Morice, tells us that among another Déné tribe named “Carriers,” there are four of these animal clans, namely, the Grouse, Beaver, Toad, and Grizzly Bear. People of the Grizzly Bear clan think that they themselves, also their ancestors, are closely connected with the Bear in some mysterious way. They respect the animal, and apologise to him when it is necessary to kill him in order to get food and clothing. The bear is thought to have a spirit which would haunt the “Bear” clan if the animal were not treated respectfully. Some Indian hunters who will have no respect for an animal belonging to some other clan, sit by the dead bear, their own totem animal, and smoke the pipe of peace, which implies that there is a good feeling between the hunter and his dead bear, whose spirit will not take revenge.

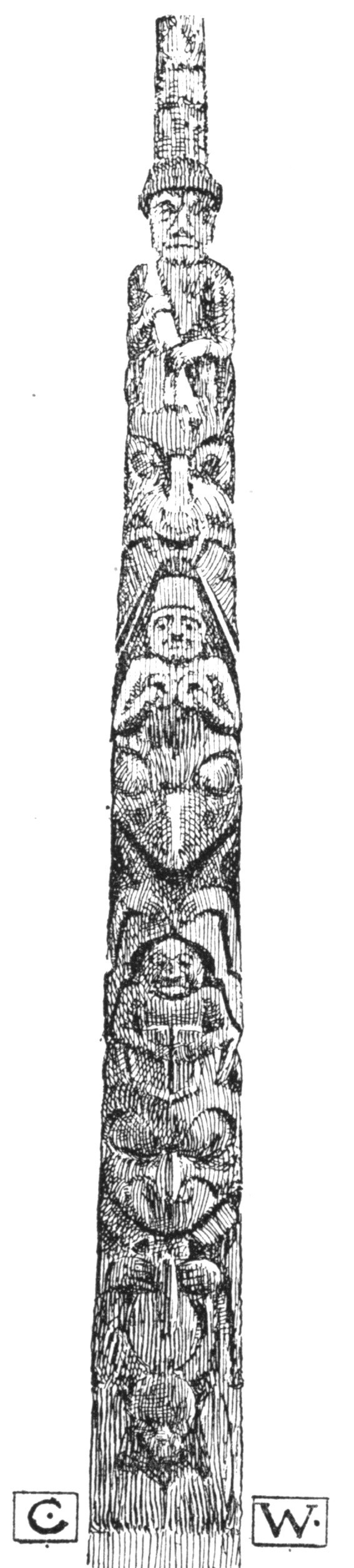

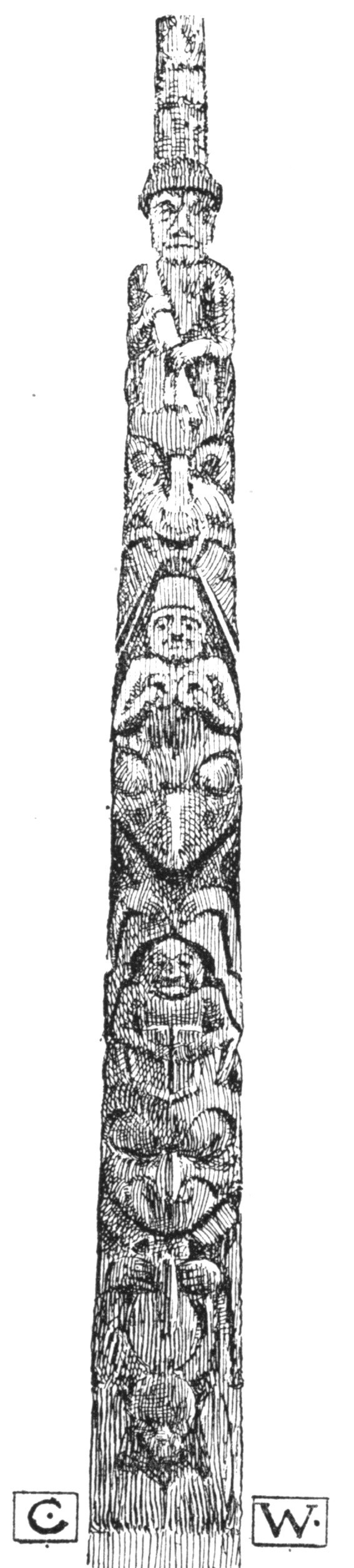

In addition to this animal “totem,” which serves as a badge for the clan, a boy always has his own special personal “totem,” which he obtains in the following way. At the age of fourteen he is subject to very harsh treatment, being beaten frequently, and driven to bathe in cold water on winter mornings. Then there is among some tribes a “sweat-bath,” which a boy enters in order to perspire out all his badness, while starvation and solitude in the woods are thought to be necessary before a boy is turned into a man who can have a “totem” animal. It is during this starvation and fasting in the woods that the boy dreams of some animal, or, as he puts it, “the ghost of the animal comes to him while he is asleep,” and the first creature which appears is his “totem,” to whom he prays when in danger and trouble. The youth must rise at once, and after killing one of his “totem” animals, he makes a little bag which is worn like a charm round the neck. Should this “medicine bag” be lost, the youth is disgraced until he has killed an enemy, and stolen his opponent’s skin bag. A chief may have more than one “totem” animal, and outside a house, say of the Haida Indians, one may see a high pole on which are carried the portraits of totem animals belonging to all who dwell within the hut. Tattooing portraits of “totem” animals on the hands and face is very common, especially among the Haida of Queen Charlotte Islands.

TOTEM POLE, 38 FT. HIGH, HAIDA, QN. CHARLOTTE IS. (NOW IN BRIT. MUS.).

Winter dances in honour of animals are very common, and at these festivities, masks in the form of animals are worn, while people caper round in imitation of the movements of their own particular totem. A very important social gathering among Salish tribes is named “potlatch,” at which presents of great value are given away by a chief who wishes to become very famous. People crowd to the top of the long cedar-wood huts, and for days there is a distribution of skins, horses, clothing, blankets, canoes, and every other form of wealth. About twenty-five years ago a great chief of Vancouver Island gave a “potlatch” to 2500 persons from different tribes. The guests were feasted for over a month, and the savings of five years were distributed; so no wonder the chief who is wealthy and a great warrior readily becomes the judge and lawgiver in Indian society.

Slaves, usually people taken in war, were at one time common, and very miserable was their lot, for they were regarded as being no better than dogs, and any man might put his slaves to death for a trifling offence. Mr. Hill-Tout, who knows the Indians well, says: “Slavery has, of course, been abolished since they came under our rule, but the descendants of those formerly slaves are still looked down upon and despised by the other Indians.”

The North-Western tribes had no belief in a Supreme Being, or in God Who made the universe, though they did think of a soul, spirit, or ghost which could survive after the body was killed. Not only people, but animals, and even weapons and articles of clothing, were thought to have a ghost which went to some other world when the creature was killed or the article broken. The Thompson Indians were very much afraid of the spirits of deer, and they always took care to bury with respect all such parts of the carcase as were not required. One way of keeping friendly with the bear spirits was to hang the skull of the animal on a tree, and all who took part in the ceremony were expected to join in a chorus praising bears, while each performer was expected to paint his face. The “medicine man,” “shaman,” or shall we say priest, is most important among Déné tribes, for this peculiar person goes into a deep sleep or trance in which he is supposed to visit the world of spirits, who tell him how to cure sick people. So clever is the “shaman” thought to be, that he is held quite capable of chasing a soul which has left the body, and when the truant soul is caught, he goes through a performance of returning it to the dying person. A man who is very ill indeed will sometimes recover just because he has such great faith in the medicine man, whose power he trusts absolutely.

Burial is performed in various ways: the body may be left on a staging concealed in the boughs of a tree, or the tomb may be a hut which was specially constructed for the dying person, or perhaps his remains are cremated. Whatever method is adopted, there is always the greatest fear of death and a return of haunting spirits, which can be kept away only by the observance of certain superstitious practices. The mourners must not eat meat for several days, then they are not to cut it with a knife. The encampment where death takes place is sometimes deserted, and what is most important, the name of the dead must not be mentioned, for the ghost may think he is called if he hears his name.

Social gatherings are made happy by the narration of stories which refer to the lives and adventures of animals. Here is one concerning a sea-gull and a raven: the former bird is credited with having kept daylight in a large box until a raven induced him to open the lid. After lighting torches and searching the seashore, the raven returned carrying prickly eggs of the sea urchin, which he strewed before the house of the sea-gull. Next day he made a call on the sea-gull, and found him in bed with his feet full of prickles, which the raven volunteered to take out with a knife. When the operation was in progress, Master Raven said: “You must open the lid of your box and let out some daylight, for I cannot see what I am doing.” So the gull opened the lid a little way, and the visitor continued taking out prickles from the sea-gull’s feet. At last the little bit of daylight was exhausted, and once more the raven asked for more light in order to continue his work. Very reluctantly the sea-gull opened the lid of his “daylight” box, but on this occasion the raven was too quick for him, and forced the lid right open, with the result that daylight rushed out, spread all over the world, and could not be gathered in again.

Sea-gull was very much distressed, bitterly he cried, and to-day the Indians say that sea birds flit along the shore, uttering their plaintive cries because of the trick played by the raven so many years ago.