CHAPTER II

SOME OCCUPATIONS OF INDIAN TRIBES

At many points along the shores of British Columbia the traveller may notice the large strongly-built dwellings of the coast Salish, who are experts in splitting stout logs from the cedar tree by means of implements made from the horns of the elk and wood of maple trees. Such large dwellings, some of which had a length of over 200 feet, were, of course, occupied by more than one family, and as a rule there were at least half a dozen hearths, each belonging to one of several closely related families who occupied the same large dwelling. The interior of the building was divided into rooms by curtains manufactured from reeds or grasses; temporary screens of this kind were easily removed when the whole room was required for winter dancing festivities, which were generally connected with religious beliefs. Extending all round the walls of the hut was a low platform, which, covered with skins and blankets made from hair of dogs and mountain goats, served as a most comfortable bed, while on its under side could be stored dried fish, roots and berries collected during summer, and vast quantities of fir cones and firewood. Such stores were frequently hidden in the forest, for years ago, before the Canadian police were known, large bands of fierce Indians, named “Kwakiutl,” from Vancouver Island preyed upon the quieter coast Salish, carrying off their women, children, and stores. Even now, says a missionary named Father Morice, the Déné are afraid of the fierce, warlike tribes who paddled their long canoes for many miles up the Fraser River.

The only pieces of furniture worth mentioning are large treasure chests constructed from planks of cedar firmly held by wooden rivets, so that the joints are quite watertight. Such boxes held blankets, costumes worn at dances, and other treasures, of which a chief owned a vast supply.

Salish tribes of the interior had two sets of dwellings, a heavy timber one for winter use, and for summer a light cool structure made by stretching mats over a wooden framework. A similar summer habitation is made by the northern Déné tribes, whose pointed tent has the appearance of a true Indian “wigwam,” and at the present time an encampment of these tribes has the same appearance as it had a century ago, when visited by the great explorer Sir Alexander Mackenzie.

Of equal importance with the building of houses is the manufacture of clothing, for which all Indian tribes have an abundance of raw material obtained during hunting excursions. The moose—which by the way is a domestic animal and beast of burden among the northern Déné—furnishes a good hide, which along with deerskin can be made into strong trousers and leggings, or into shoes named “moccasins.” Blankets, forming a covering for the shoulders and body, are made from wool of the mountain goat, and in some cases, down from ducks is interwoven with the fabric, which is made by use of the old-fashioned spindle. Among the interior Salish a man usually possesses a shirt, trousers, leggings, moccasins, and cap. The shirt and trousers are generally made ornamental by fringes of deerskin, while to the moccasins are added dyed porcupine quills, goose feathers, or horse hair. Winter socks are made from skins of the bear, buffalo, or deer, but in summer these are replaced by lighter socks, manufactured from grass and cedar bark. Small animals, such as the fox, lynx, hawk, and beaver, furnish material suitable for caps, and among the “Thompson” Indians a man always made a cap from the covering of what an Indian calls his “totem,” that is, an animal which he believes to be his own special friend and helper.

The summer dress[1] worn by women did not differ much from that of the men, save that it was longer, and usually ornamented with claws and teeth of the beaver. A chief’s dress was very elaborate, and the most interesting part of his costume consisted of a cap made from the hair of women from noble families. Most boys are acquainted with tattooing, which is very common amongst soldiers and sailors nowadays. A favourite Indian pastime was the tattooing of figures representing animals; and sometimes the chin, forehead, or cheeks would be ornamented with tattooed designs of some animal, usually the “manitou,” or creature which a boy selected for his companion and guardian through life.

A good many occupations are connected with the food supply, and everywhere near the coast or the banks of Fraser River there are Indians busy catching, cleaning, drying, and extracting oil from fish, among which the salmon is most prized. Gathering quantities of roots, berries, and nuts is a favourite occupation with women and children, who are made responsible for laying in large quantities of vegetable food for winter. While men are occupied with hunting and fishing, women collect roots of the cedar tree, and from the bark of these baskets of varied patterns are neatly manufactured. Human and animal designs are interwoven with pieces of coloured fibre in such a way as to give an ornamental effect, though the Indian’s idea is not merely decoration, but a desire to portray the animal helpers which he holds in reverence. Very light vessels may be made from bark of birch and spruce trees; some hold several gallons, and may be held on the back by leather thongs, one of which passes round the forehead of the carrier. Canoes of birch bark are so light that they can be carried across land for several miles, and travellers have many times crossed from Hudson Bay to Vancouver chiefly by use of these light portable canoes.

The manufacture of bows and arrows is an important undertaking, for on these the hunter’s life and food supply entirely depend. Very great care is taken in providing a bow string which will not be affected by damp, and after threads of sinew have been neatly plaited into one strand, the whole is rubbed with glue from the sturgeon, or perhaps with gum from the black pine tree. Some tribes provided the end of the bow with a sharply pointed stone, so that the implement could be used as a thrusting spear when an animal came to close quarters, and the hunter had not time to fit another arrow. Willow and mountain maple are tough, elastic woods suitable for the bow, which is always strengthened by a layer of sinew, cherry-tree bark, or snake skin, which is glued to the wood. Barbed and leaf-shaped arrow or spear points are used for hunting and warfare. Rock crystal, quartz, and a hard, dark, shiny stone named obsidian are most serviceable for weapons; poison made from fangs of the rattlesnake is used as a varnish for these stone arrow points, so the hunter must be very careful that he does not scratch himself when fitting an arrow to the bow. Metal plays an ever increasing part in the Indian’s outfit, but there are still many knives, daggers, war clubs, spears, and tomahawks, in the manufacture of which sharpened stone is employed. “Tomahawk” means a skull cracker, and no better name could have been employed, for this implement pecks out a little circular hole in the skull, and many graves have been opened in which the skeleton shows plainly by what instrument the fatal blow was delivered. No stone implement is more prized than the hammer, which takes a great deal of chipping and rubbing from hard stone. During long evenings men will sit round the fire talking and polishing their hammers, merely rubbing with the palms of the hands; the implements take a very smooth gloss, and are handed down from father to son for many generations.

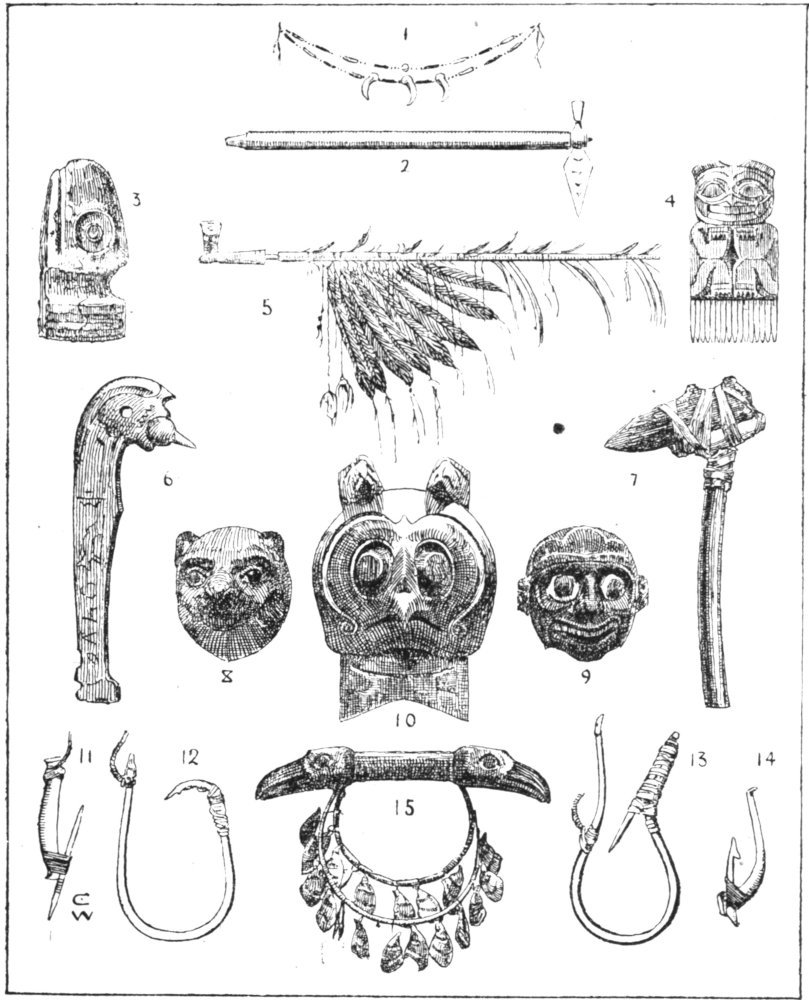

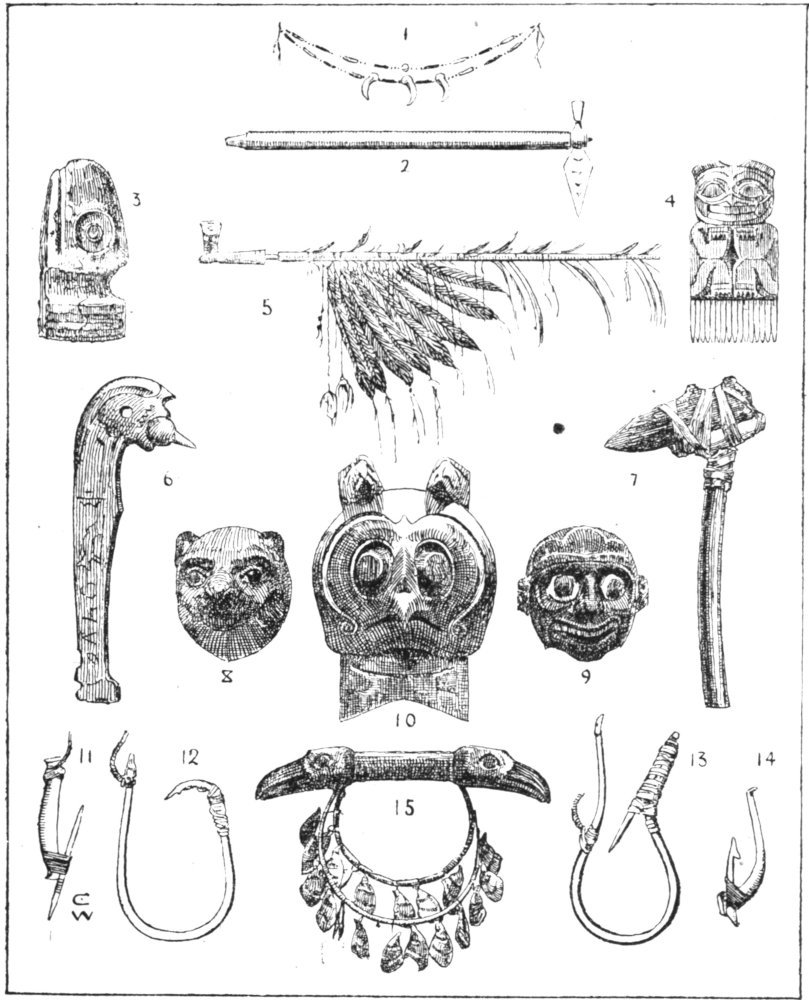

NORTH AMERICAN IMPLEMENTS, WEAPONS, ETC.

1. Necklet of Wampum (shell) and bear’s claw.

2. A pipe-tomahawk.

3. A stone club-head.

4. Wooden comb representing a beast.

5. A peace-pipe.

6. A spiked tomahawk (skull cracker).

7. A stone-bladed axe.

8, 9, 10. Wooden masks from Vancouver Island. These represent the spirits of a beaver, a cannibal, and an eagle; they are worn during dances held in honour of these spirits.

11, 12, 13, 14. Fish-hooks. No. 11 is made of stone and wood; No. 12 is tipped with a bird’s claw; No. 13 is for halibut, and is tipped with bone; No. 14 is wood tipped with bone.

15. Rattle of puffin beaks used in dances by the Haida of Queen Charlotte Islands.

[1] For details of customs which still survive, also for information concerning practices which have fallen into disuse, see books recommended for the teacher’s reference library.