CHAPTER V

THE ESKIMO AS A HUNTER

The Algonkin Indians were so disgusted with the habits of life adopted by the Innuit, that they called them “Eskimo,” a name which means “eater of raw flesh.” It would be difficult to find a much better description, for so barren is the snow-clad country, and so intense the cold, that the Eskimo has no opportunities for practising agriculture; neither would vegetable food sustain life in this inhospitable region.

The fatty diet is obtained chiefly from the seal, whale, and walrus, while the reindeer, together with an abundant supply of sea birds and fish, furnish food and clothing. An encounter with polar bears is not looked upon as a regular part of the hunter’s life, and a successful combat with one of these animals is an event talked about during many a long winter evening. So proud is the hunter, that he tattoos himself with special marks indicating how many whales or polar bears he has taken; one great hunter had across his chest tattooed marks in the form of the flukes on the tail of a whale. These showed that he had killed seven of these creatures; and such was the pride of his wife, that she had tattooed herself in the same way.

Seal hunting is perhaps the most common means of obtaining a large supply of food and material for clothing, and usually the animal is harpooned, though the method of capture depends on the season of the year and the condition of the ice.

The shaft of the harpoon, to which a line is attached, is made of wood, strengthened by a thong of reindeer hide. The head consists of a sharply pointed piece of ivory, probably obtained from the tusks of the walrus; and in order that the sharp point may detach itself in the wounded animal, the head fits very loosely in the shaft, to which it is fastened by a strong thong of reindeer sinew. The floating wooden shaft, to which a bladder is fastened, is plainly seen each time the wounded animal comes up to breathe. The whole proceeding has been described by Dr. Boas, who says:

“When the day begins to dawn, the Eskimo prepares for the hunt by gathering his harpoons and harnessing the dogs to the sledge. The harpoon line and the snow knife are hung over the deer’s antlers, which are attached to the hind part of the sledge, a seal or bear skin is lashed upon the bottom, and the spear secured under the lashing. The hunter takes up the whip, and the dogs set off at a great pace for the hunting ground.

“Near the place where he expects to find seals, the hunter stops his team and takes the implements from the sledge, which is then turned upside down in such a way as to prevent the dogs from running away. A dog with a good scent is then taken from the team, and the Eskimo follows his guidance until a seal’s hole is found. In winter it is entirely covered with snow, but generally a small elevation indicates the situation. The dog is led back to the sledge, and the hunter examines the hole to make sure that it is still visited by the seal. Cautiously he cuts a hole in the snow covering and peeps into the excavation. If the water is covered with a new coat of ice, the seal has left the hole, and it would be in vain to expect its return. The hunter must look for a new hole promising better results.

ESKIMO SEAL HUNTER WAITING AT BREATHING HOLE.

“If he is sure that the seal has recently visited a hole, he marks its exact centre on the top of the snow and then fills up his peep-hole with small blocks of snow. These preparations must be made with the utmost caution, as any changes in the appearance of the snow would frighten away the seal.”

The hunter stands on a small piece of seal skin with the harpoon poised in both hands, and there he may have to wait for several hours; sometimes he builds a screen of snow to protect himself from the bitterly cold wind. Now he bends low, and listens intently for the blowing which indicates that a seal is at hand; then suddenly he stands upright, and with all his strength sends down the harpoon into the hole, where the seal is in such a position that it usually receives the weapon in the head. The line is paid out, and at the same time the hunter cuts down the snow covering from the hole, to the edge of which the animal is dragged, and dispatched by a blow on the head.

The blood of a seal is highly prized, and to prevent waste all wounds are closed by driving in ivory pegs; sometimes the hunter refreshes himself with a copious drink of the warm blood.

In the month of March, mother seals prepare long burrows in the snow, and here the Eskimo finds the baby seal, which is dragged forth by means of a large hook; the mother, too, is often caught or harpooned because of her courage in attempting to save her young. Perhaps these methods of hunting appear to be somewhat cruel, but it is to be remembered that the Eskimo is constantly fighting hard to sustain life in a severe and inhospitable climate. On some occasions the hunter finds only the skin of a young seal in one of these burrows; the foxes have arrived first and devoured the carcase. With the advance of summer the young seal breaks from its snow burrow, and, until the end of June, the mother and her calf may be seen basking together on the ice, where they are shot or harpooned by the hunter, who, clad in seal skin, can approach to very close range. Many men still prefer a harpoon to the guns which may be obtained from whalers in exchange for skins, but nowadays the head of the harpoon is usually made of iron, which is more effective than sharpened ivory. This method of stalking the seal may produce a bag of from ten to fifteen animals in a day, whereas the winter tactics rarely result in the capture of more than one animal even after twelve hours of weary waiting by the breathing hole.

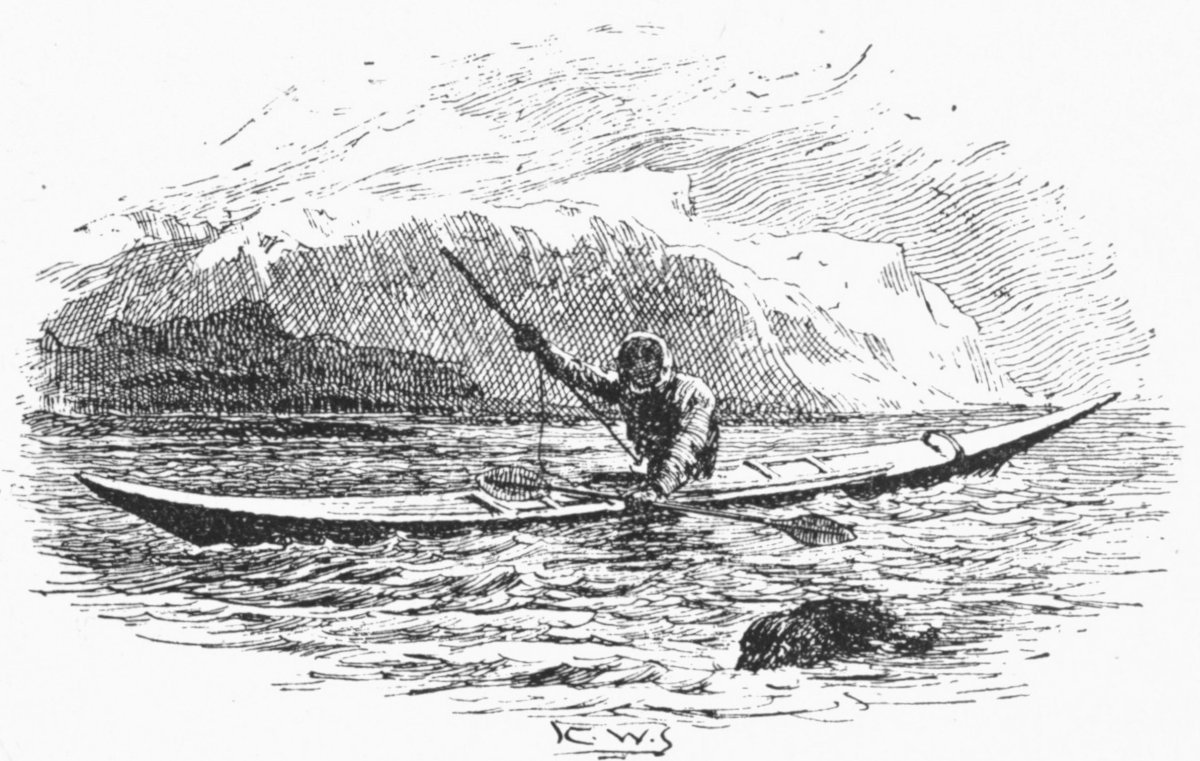

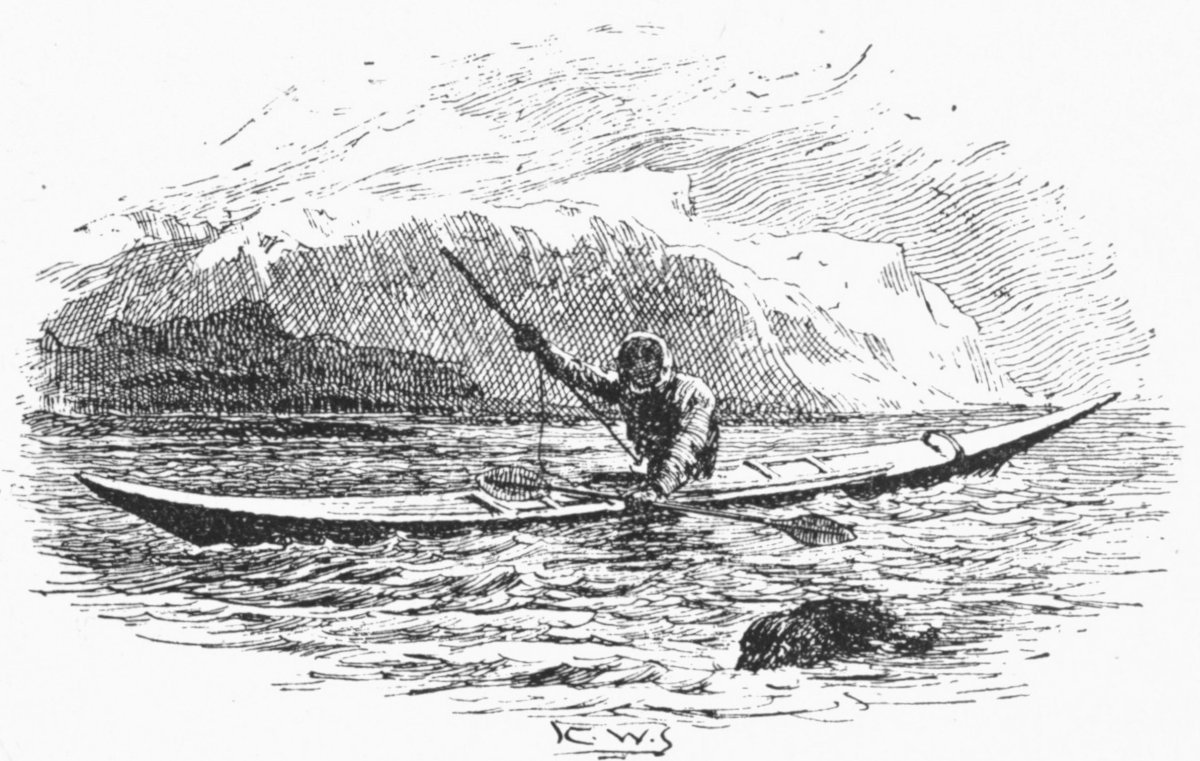

When the ice breaks, “kayaks” are launched, and the summer hunting of the seal and walrus is soon in full swing. The double pointed canoe, which is widely distributed between the shores of Greenland and Alaska, consists of a stout framework of wood and whalebone, twenty-five feet long, over which are stretched seal skins, sewn firmly together with the sinews of reindeer. The top is covered by skin, with the exception of a small hole just large enough to accommodate a man’s body; a double paddle serves to propel the craft, which is, of course, provided with a large harpoon when used for pursuing a seal or walrus.

A KAYAK.

Sometimes a framework covered with skin is attached to the harpoon line in such a way that when the cord is paid out the broad framework is dragged through the sea at right angles to the line. How great is the resistance of the water to such a device may be illustrated by holding the edge of a piece of board while dragging it in water. Of course a wounded animal is quickly exhausted by towing this apparatus rapidly through the sea. An explorer named Lyon has left a very interesting account of one method adopted by hunters of the walrus:

“When the hunters in their canoes perceive a large herd sleeping on the floating ice, as is their custom, they paddle to some other piece near them which is small enough to be moved. On this they lift their canoes and then bore several holes through which they fasten their tough lines, and when everything is ready they silently paddle the hummock towards their prey, each man sitting by his own line and spear. In this manner they reach the ice on which the walruses lie snoring, and if they please, each man may strike an animal, though in general two persons attack the same beast. The wounded and startled walrus rolls instantly to the water, but the harpoon being well fixed he cannot escape from the hummock of ice to which the Eskimo have fastened the line. When the animal becomes a little weary, the hunter launches his canoe, and, lying out of reach of the animal’s fearful tusks, spears him to death.”

At one time whaling was a favourite occupation of the central Eskimo, and in some places it is continued to the present day, chiefly by pursuing the whale with a great number of kayaks and skin boats of a larger pattern. The creature is followed by numerous hunters, each of whom endeavours to drive his harpoon into the animal, which, from loss of blood and the resistance caused by harpoon lines, floats, and framework, is tired out, and killed with lances.

During the very short summer, herds of deer wander in search of herbage, and the Eskimo follows on foot in order to secure a supply of deer skins, which are fit for clothing only when taken at this period. The snow huts have been abandoned, and the hunter takes with him a light portable tent of reindeer hide, which is often pitched near the shores of a lake habitually crossed by the herd. Sometimes the hunting party is divided, and while some men drive the frightened animals into the water, others sit in “kayaks” waiting for the deer to swim by. A lake into which a long narrow peninsula projects is considered very suitable, for a number of hunters extended in skirmishing order can drive the herd along the narrow projection of land, and eventually into the lake. Kayaks are propelled more quickly than the animals can swim, so they are overtaken and killed with the spear. At times the deer does a little hunting, and if provided with a stout pair of antlers he will rip open the boat and make the Eskimo swim hard for the shore.

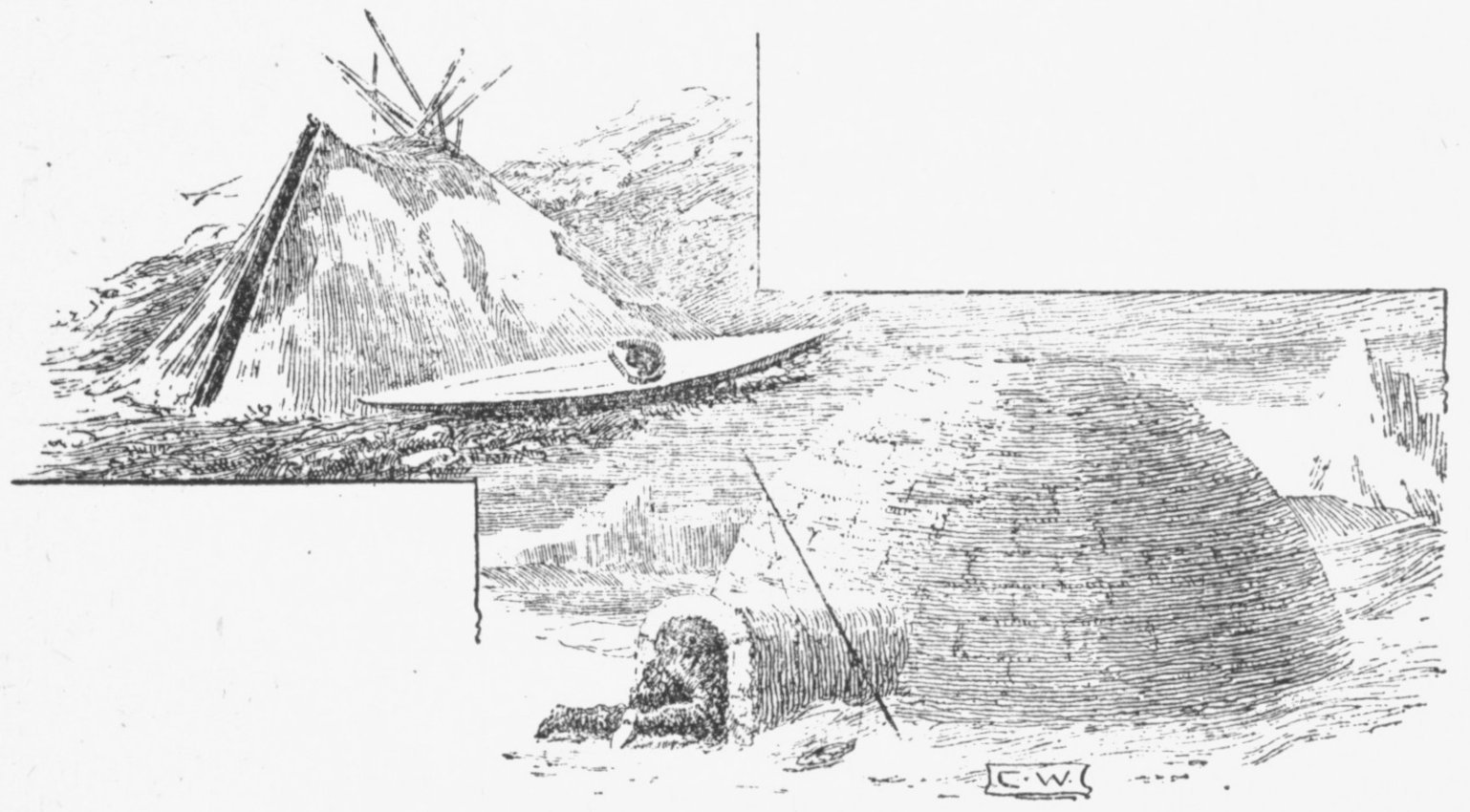

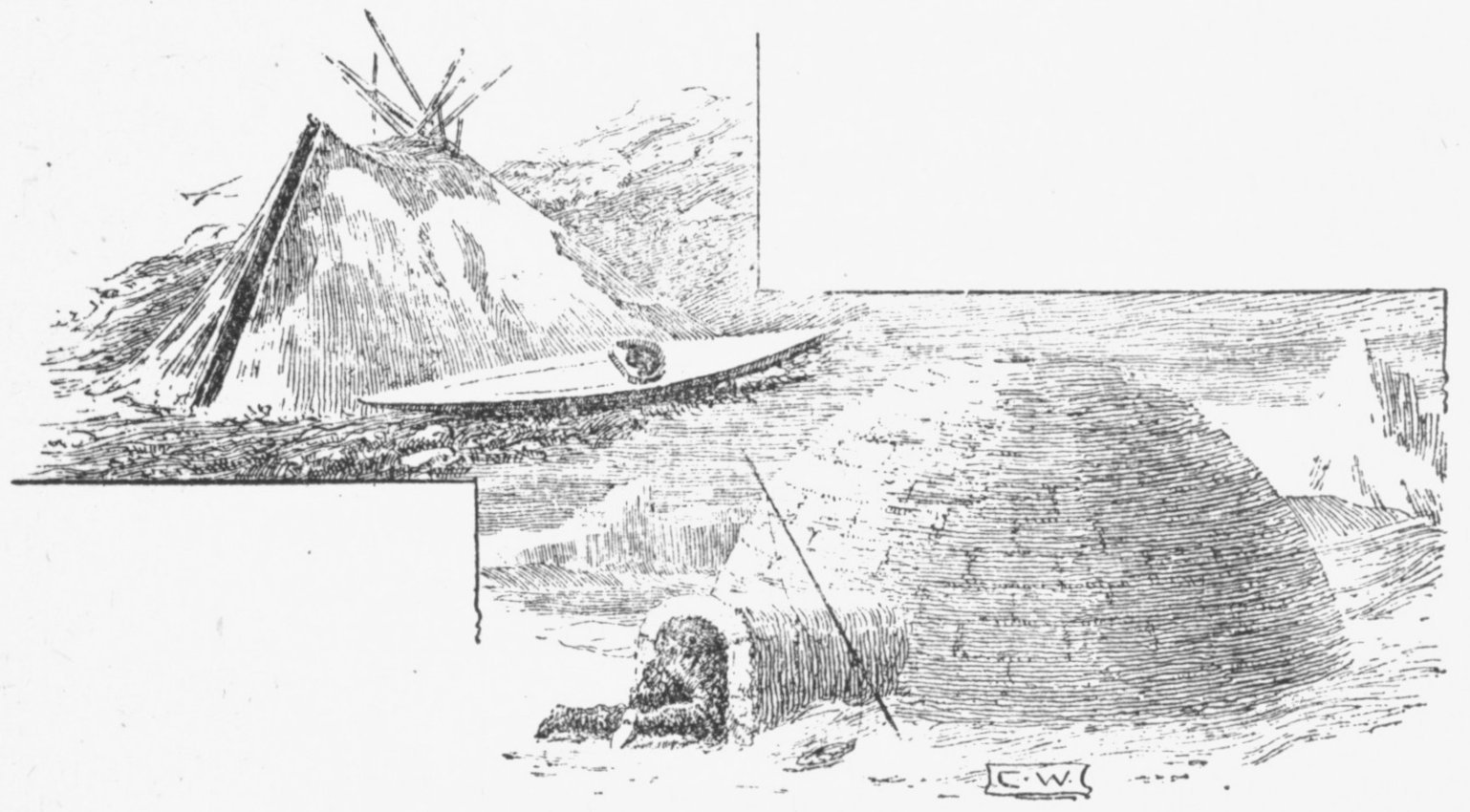

ESKIMO SUMMER TENT OF BEAR SKIN AND SEAL SKIN, AND SNOW HUT.

In some instances the herd is driven along a deep narrow valley with steep sides, and as there is no means of escape, the animals are killed by hunters extended in line at the narrowest part of the defile. Bows are made either of wood or antlers of the deer, and as a rule the wooden weapon is made stronger and more pliable by the addition of a strong strip of sinew, which is bound firmly to the wooden portion. The bowstring is manufactured from sinew; and the arrow tips, formerly cleverly made by flaking pieces of slate, are now replaced by sharpened scraps of tin or iron riveted into a slit at the pointed end of the shaft, to the other extremity of which a few feathers of the owl are fastened in order to give a true flight. A large quiver of seal skin is divided into compartments containing the arrows, the bow, and a number of spare arrow tips. A handle of ivory serves as a means of carrying the quiver when the hunter is travelling, but as soon as game is in sight, the quiver is slung over the left shoulder.

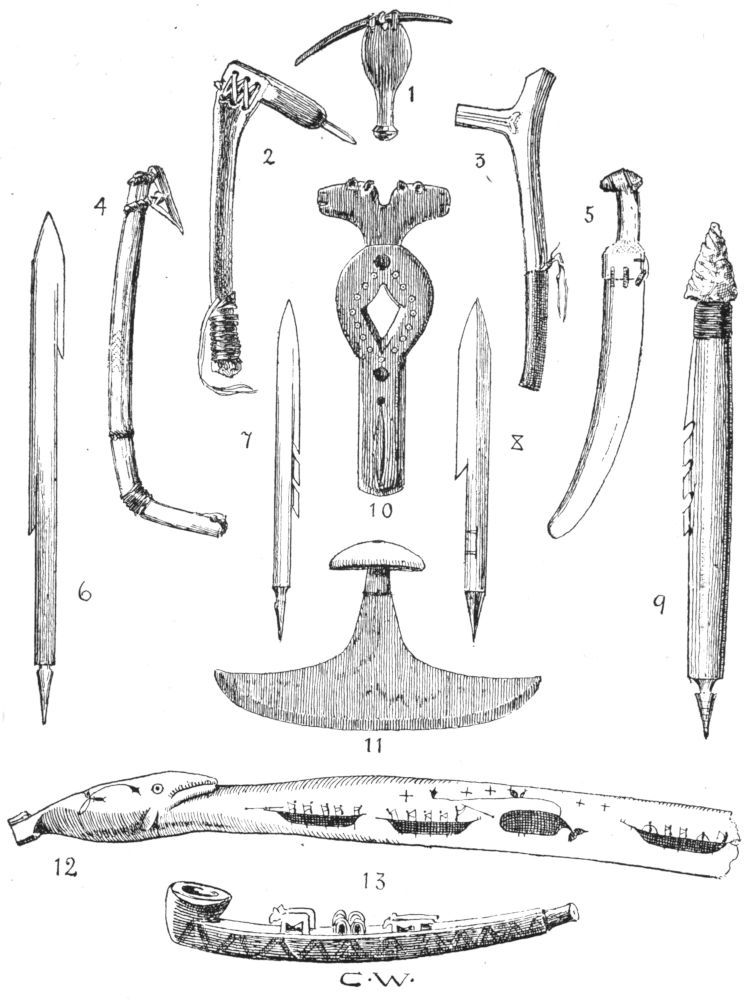

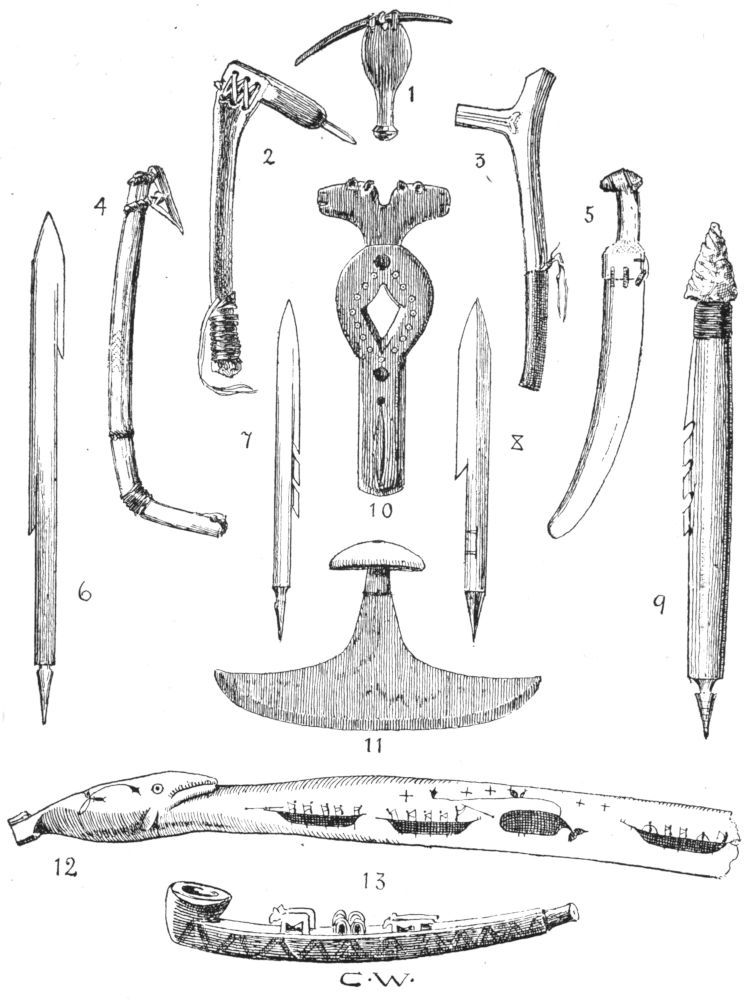

ESKIMO TOOLS, WEAPONS, ETC.

1. Pick of wood and ivory;

2. Adze of bone and iron;

3. Antler club;

4. Gaff for salmon;

5. Snow-knife of bone;

6, 7, 8, 9. Arrow heads of antler; No. 9 is pointed with stone;

10. Arrow straightener of bone; 11. Hide scraper of bone and iron;

12 Carving on ivory depicting a whale hunt;

13. Tobacco pipe of ivory.

Eskimo dogs are eager in the pursuit of herds of the musk ox, which always defends itself by forming a circle around the calves. While the oxen are busy keeping a number of ferocious dogs at bay, the hunters approach and let fly their arrows into the herd. Sometimes an infuriated animal breaks from the defensive ring, and at such times the Eskimo is saved by his dogs, who harass the creatures until the hunter is again prepared to shoot. Polar bears are pursued by hunters on light sledges, and when the quarry is exhausted by the chase, the traces of the most reliable dogs are cut, and very soon the bear is standing at bay, striking fiercely at the dogs with his huge forepaws, until the hunter is able to come up and launch a spear or arrow. The best season for bear hunting is March or April, when the bears come a considerable distance inland in pursuit of young seals. In the region of Davis Strait, the Eskimo diligently search for holes where the bear is having his long winter sleep, from which the hunter intends that he shall never be awakened.

ESKIMO DOGS’ ATTACK ON A BEAR.

Hunters do not consider wolves sufficiently valuable to repay the trouble of pursuit, and these creatures are ignored unless they prove dangerous to the Eskimo encampments. Traps for wolves consist of a hole ten feet deep, very small at the bottom, but gradually widening towards the circular top, which is surrounded by a snow wall. A thin sheet of ice covers the wide top, in the centre of which some strongly smelling meat is placed. In order to get the bait, the wolf must leap the snow wall, with the result that he crashes through the thin covering of ice, and is soon trapped at the narrow base of the pit. A very cruel method of killing wolves consists of rolling a very sharp piece of whalebone inside a piece of meat, which is eagerly gulped down by a hungry animal. The meat digests and dissolves, and before long the wolf suffers very great pain, for the whalebone coil unwinds and the sharpened ends penetrate the walls of the stomach and intestines.

Small game, such as foxes, hares, ermines, and lemmings, are caught in snares, while for birds the following clever contrivance is frequently employed. “It consists of seven or eight sinew cords, nearly three feet long and tied together at one end, while to the opposite ends weights of ivory or stone are attached. Before being launched at the bird, the sling is whirled round the head, so that when it leaves the hand a rotatory movement is imparted to it, and all the weights fly apart, the striking diameter of the weapon covering five or six feet. The bird is thus brought to the ground, whether it is struck by the weights or entangled in the strings.”

A favourite method of catching gulls depends entirely on the quickness of the hunter, who has concealed himself in a small snow house, one block of the roof of which is made from a thin, transparent piece of ice to support the bait. When a bird settles on this thin ice, the trapper quickly pushes his hand through, seizes the creature, and drags it into the hut. By far the greater number of birds are caught in the moulting season, partridges by hand, and waterfowl after pursuit with the kayak. Swimming birds dive as soon as the boat comes near them; immediately they are pursued, and time after time are driven down whenever they attempt to breathe at the surface; eventually they are drowned, and the bodies float on the water.

Fish, among which the salmon is very plentiful, are harpooned, taken by ivory fishing hooks, or chipped out of blocks of ice in which they have become deposited at the freezing of a small lake, which may have been converted into a solid mass of ice. The scraping, chewing, and drying of skins is one of the chief employments of women, and so careful are they, that no part of the carcase is wasted, and even the intestines of a seal are made to furnish transparent waterproofs, which are, of course, very light and convenient to carry. Driftwood from the seashore is used in making bows and sledges, while the antlers of the reindeer help to form smooth runners, and the sinews give elasticity to wooden bows. Knives, scrapers, hooks, utensils, prongs of harpoons, and arrowheads, all depend for their manufacture on supplies of ivory and bone, in the working of which the Eskimo is most ingenious. Strange to say, the caves of very ancient Europe, when excavated, have sometimes yielded specimens of engraved ivory very closely resembling the products of the Eskimo. From the caves La Madeleine and Bruniquel are derived some excellent specimens of engraving on bone, an art which flourished in some parts of Southern Europe towards the end of the old Stone Age. The question of the origin and migrations of the Eskimo, together with speculations concerning their connection with the bone workers of ancient Europe, are very interesting, but perhaps too long and difficult for a small reading-book.

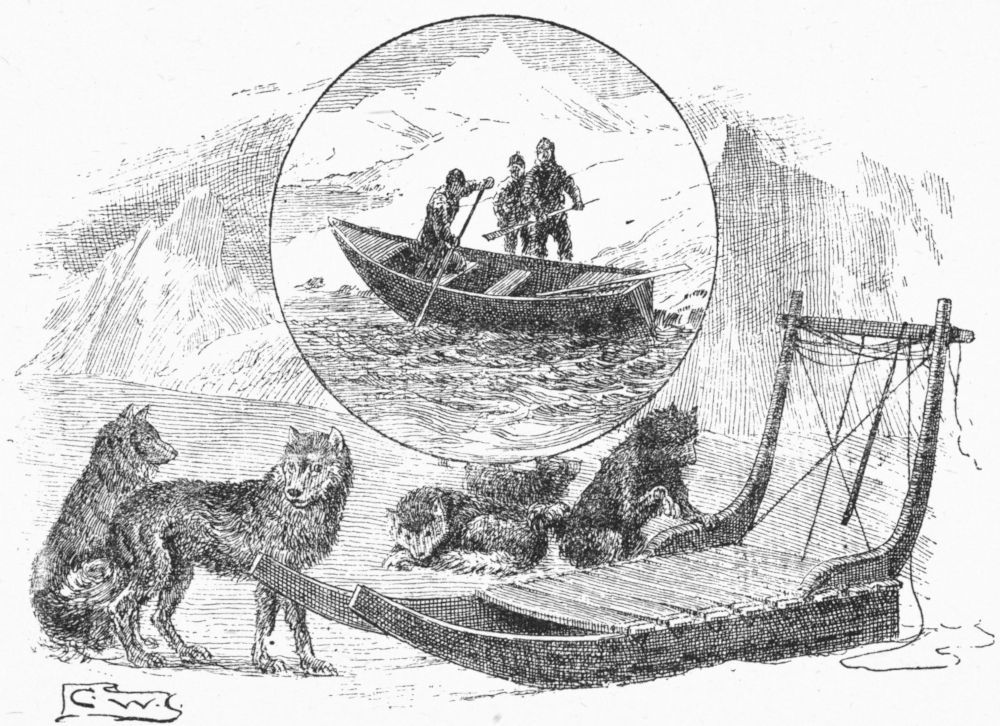

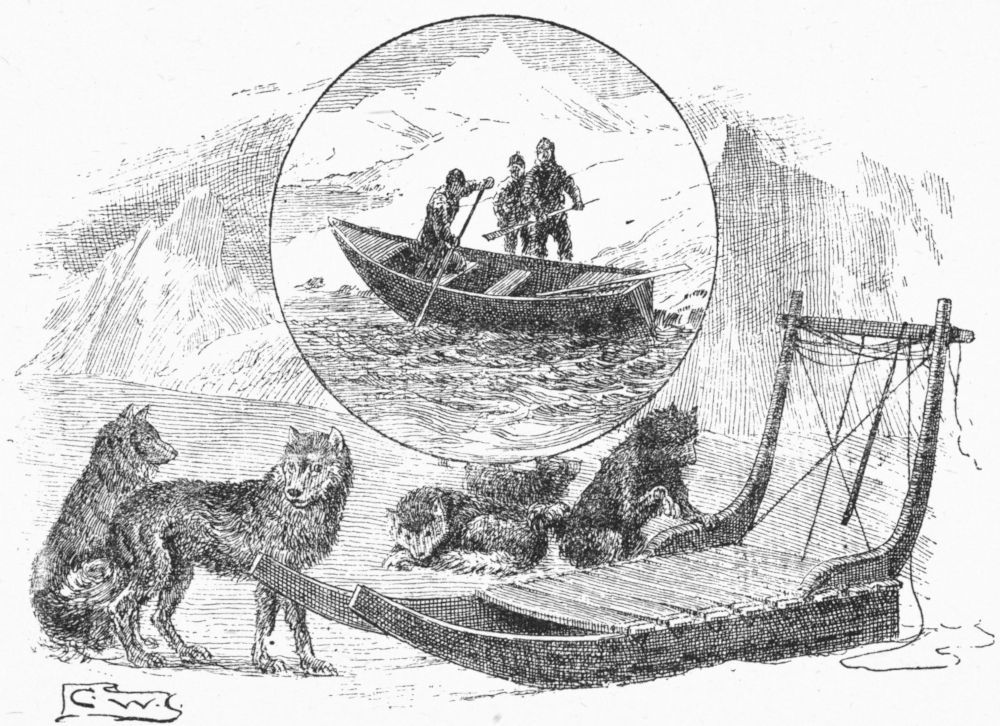

In addition to the kayak already described, women use a large open boat shaped like a trough and capable of holding about twenty people. With this “umiak” single-bladed paddles are employed, and a low lug-sail made of strips of walrus-intestine is sometimes hoisted. For steering, a paddle is used, and a rudder is to be found only when the Eskimo have copied the steering device from European whalers.

A UMIAK AND ESKIMO DOGS AND SLEDGE.

The best sledges are made by the tribes of Hudson and Davis Straits, for in these regions the most substantial pieces of driftwood are to be found. The dog team is strong, intelligent, and willing to work; so ready to start that the Eskimo driver may be in danger of being left behind. Careful training of the animals is necessary, and sometimes there is a great deal of harshness before they are fit to harness; perhaps the worst qualities of the dogs are extreme ferocity and pugnacity. Dr. Boas says:

“The Eskimo rarely brings up more than three or four dogs at the same time; and if the litter is larger than this number the rest are sold or given away. The young dogs are carefully nursed, and in winter they are allowed to lie on the couch, or are hung up near the lamp in a skin cradle. When almost four months old the pups are first put to the sledge, and gradually they become accustomed to pull with the others. If food is plentiful the dogs are fed every alternate day, and then their share is by no means a large one. In winter they are fed with the heads, entrails, bones, and skins of seals, and they are so voracious at this time of the year that nothing is secure from their appetite. Any kind of leather, particularly books, harness, and thongs, is eaten whenever they can get at it. In the spring they are better fed, and in summer grow quite fat, but at any time of their life food may not be procurable for five or six days. In Cumberland Sound, Hudson Strait, and Hudson Bay, where the rise and fall of the tide are considerable, the dogs are carried in summer to small islands, where they live upon what they can find on the beach: clams, codfish, etc., and if at liberty, they seem very happy, and well able to provide for themselves.”

Dr. Boas remembers two runaway dogs which had lived on their own account from April to August, during which month they returned quite fat.