CHAPTER VI

TALES TOLD BY THE ESKIMO

INTERIOR OF AN ESKIMO SNOW HUT.

If we could creep along the narrow underground passage leading to the snow hut, we might have the good fortune to find the Eskimo family crowded together round the small, evil-smelling oil lamp, which from time to time is replenished by a new supply of fat from the seal or whale. Around the small, dome-shaped snow dwelling are low seats constructed from blocks of frozen snow, which, covered with several layers of skin and fur, make comfortable couches for the inmates. Already the small room has become so warm that most members of the family have cast aside their outer fur garments, and each person is settling down to the evening task. The women are busy chewing skin of the reindeer in order to make it soft and pliable, so that it may be sewn into boots and jackets, while the men are constructing harpoons, mending harness for the dogs, or perhaps cleverly engraving small sketches on pieces of ivory obtained from the tusks of the walrus.

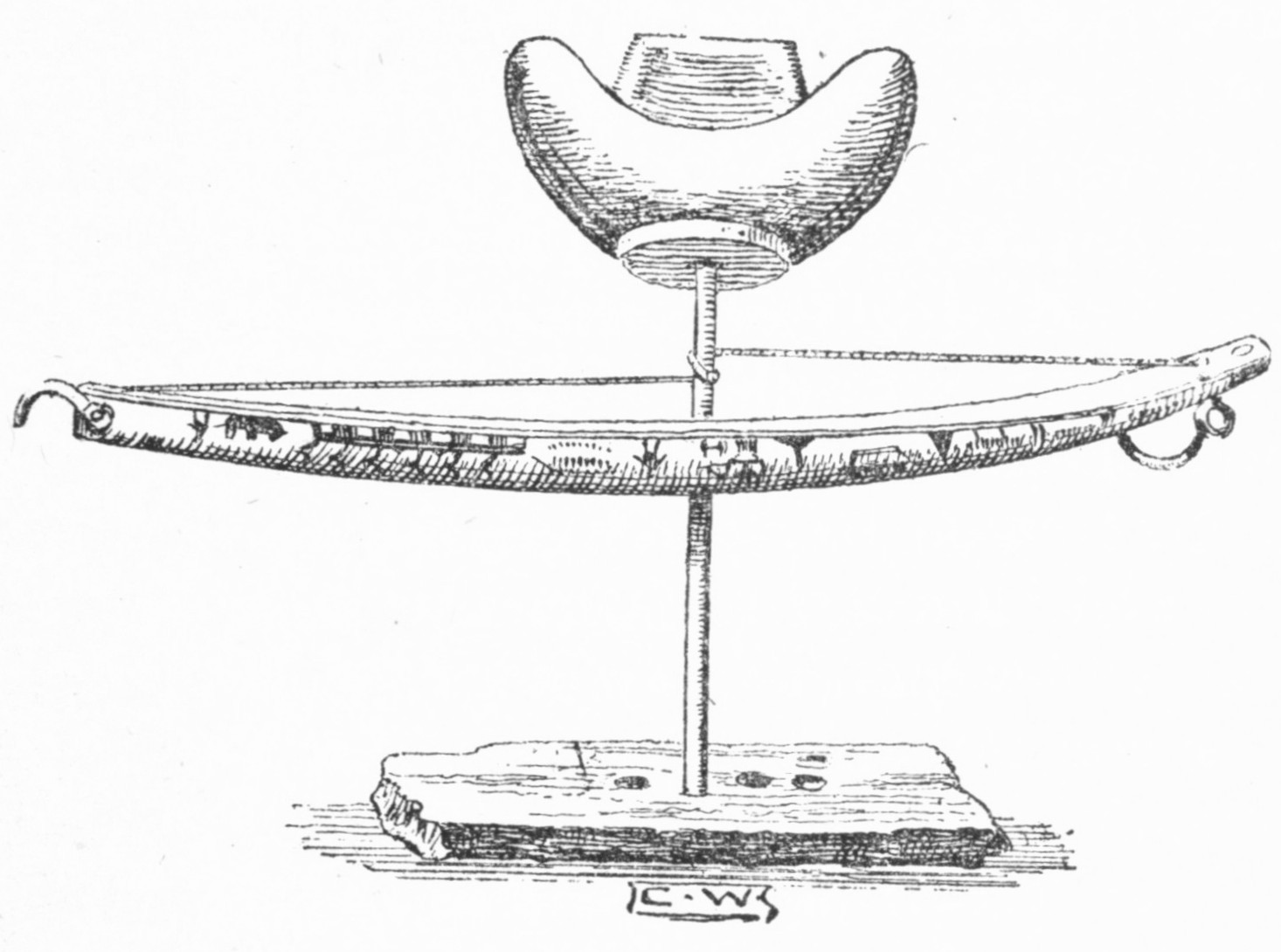

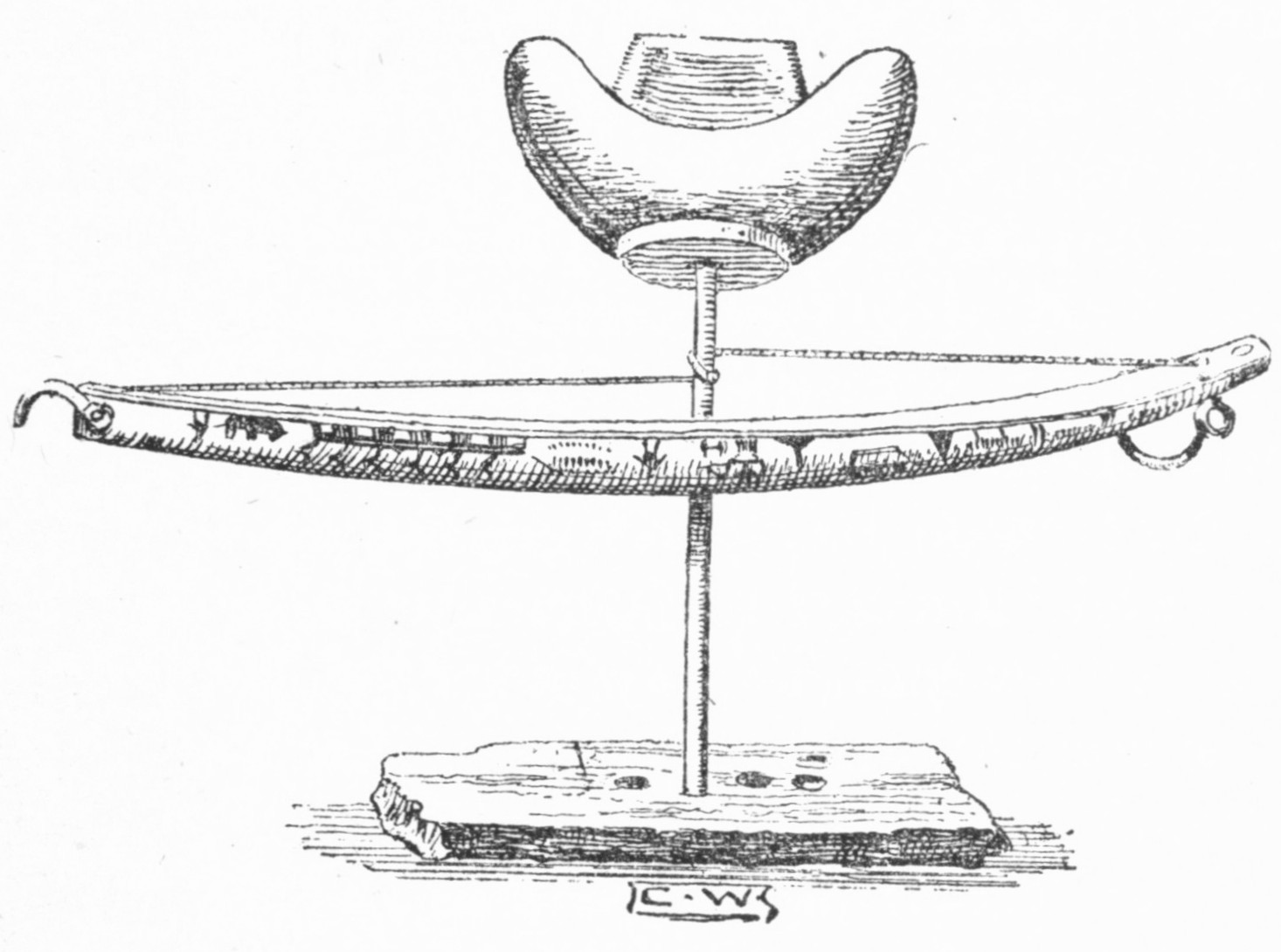

ESKIMO BOW-DRILL FOR FIRE MAKING.

Oil lamps are kept burning day and night in winter, but should the Eskimo require a light he can quickly produce it by means of the bow-drill. A peg of hard wood rests in a hole in a soft board, and near to the point of contact is a small pile of tinder; that is very finely powdered wood, which is kept quite dry. The peg of hard wood can be made to spin round rapidly by twisting it in a bow string, which is made tight, then released suddenly. Boys at school adopt a similar method for spinning a disc of cardboard, or setting a toy aeroplane in flight. The rapid twirling of the hard peg sets up a great deal of heat, which causes the tinder to smoulder, then to burst into flame when gently blown.

Presently the work is put on one side, and after a hearty meal has been made from the flesh and warm blood of a young seal, stories of great age are told concerning the perils of the hunter, and the wanderings of the Eskimo people over the great ice-fields of Hudson Bay or Davis Strait. Eagerly we listen, and although the names are very long and strange to our ears, we may judge that the favourite stories are not unlike our own tales of love and valour, with this exception, that the Eskimo has no knowledge of writing, so stories are handed down from one generation to another by word of mouth, while, to amuse the children, the story-teller will make little sketches of the chief characters in his narrative.

A long, long time ago a young man, whose name was Itit, went timidly to the hut of a young orphan girl, in order to ask whether she would become his wife. However, as he was very shy, and afraid to speak to the young girl for himself, he called her little brother, who was playing before the hut, and said: “Go to your sister, and ask her if she will marry me.” Away ran the little fellow, but almost immediately he was back again in order to ask the name of the suitor. When the Eskimo maiden heard that the name “Itit” was the short pet name for “Ititaujang,” she said: “Oh, go away! I will not marry a man with such an ugly name.” Three times the young brother carried a message of love from the poor Itit, who was becoming very cold and angry, for he had been standing in deep snow for a long time. When the maiden refused for the third time, Itit turned away from the hut, left his own country, where there was no other maiden whom he could love, and for many days and nights he wandered, sad and lonely, over great hills and valleys covered with snow.

At last he arrived in the land of birds, and saw a lake on which geese were swimming. On the shore he noticed a great many boots, so cautiously he crept near and stole as many as he could carry. The birds returned, and greatly alarmed at this theft, they flew away, with the exception of one bird which remained behind, crying, “I want my boots! I want my boots!” “You shall have your boots,” said Itit, “if you will become my wife.” Then, returning the magic boots, he had the pleasure of seeing the beautiful bird transformed into a handsome young Eskimo maiden, who wandered with him to the seaside, where they settled in a large village. Itit became the best whaler and seal catcher, so was very much respected by all the Eskimo of that country; and what was more pleasing still, he had a young son who was rapidly becoming a brave and clever hunter.

It so happened that the Eskimo, led by Itit, had killed a whale, and all except the wife of Itit were busy carrying the meat and blubber to their huts. When the lazy wife was called, she answered: “I do not like food from the sea, I want all my food from the land. I will not eat the meat of a whale, and I will not help.” She came down to the beach leading her young son by the hand, and after finding some feathers, she placed them between her fingers and those of her son, both twirled their hands quickly, and on whispering some magic words were changed into geese, which flew away, leaving Itit to carry out a sorrowful search for his wife and child.

After many weary months of travel he came to the bank of a swiftly flowing river, where an old man was striking off chips of wood, which, when polished between his hands, turned into little salmon, that leaped into the water and began to swim towards a large lake. Itit at once asked questions concerning his wife and child, and to his great surprise learned that they were dwelling on a small island in the lake. He was furious on hearing that his wife had taken another husband, and now he loved her no more, but sought only for revenge. There was no canoe, but the clever old man, who could make salmon from chips of wood, took the backbone of a fish, and after vigorously polishing this for a time, it turned into a small boat which the Eskimo calls a “kayak.” This the old man presented to Itit, who immediately pushed off from the shore in the direction of the island where his wife was hiding.

Very soon a small hut came into view, and there was his son, playing in the garden. The little boy ran into the house, crying, “Mother! Father is here, and is coming to our hut!” to which the mother replied, “Go on with your play; your father is far off, and cannot find us.” No sooner were the words spoken than Itit entered and glared fiercely round the room, while the frightened woman quickly opened a box from which there flew a cloud of feathers. These stuck to the woman, her son, and the new husband, and before Itit could carry out his revenge, the hut suddenly disappeared, and his enemies, immediately transformed into geese, flew rapidly away until they became mere specks in the distance.

Among our own boys and girls, stories of Father Neptune, who lives on the bed of the ocean and rules the waves, are very common. The Eskimo, too, have traditions of “Kalopaling,” who seems to be very much like the “Old Man of the Sea,” mentioned in stories of Sinbad the Sailor. To the Eskimo, Kalopaling is a dreadful monster of human form, covered with feathers of the eider duck, and so large is the hood of his cloak that it will easily contain a kayak and the fisherman who sculls it. This hood is said to be filled with Eskimo fishermen who have either been drowned by accident or captured by the dreaded Kalopaling, who, although unable to speak, can make a long wailing cry of “bee-bee-bee.” The feet of this creature are very large, and appear like sealskin floats, or the water wings which boys use when learning to swim.

The Eskimo believe that in olden times there were a great number of “Kalopaling,” but happily their numbers are diminishing, and now only a few of the strongest are left. These are often seen swimming a few feet below the surface of the sea, and from time to time they rise in order to breathe, then once more disappear below the surface with much splashing of arms and legs. The hunter has only one chance of killing a “Kalopaling,” and this must be done when the monster is asleep on the ice. The flesh is said to be poisonous, but it may be used for fattening dogs that draw the sledges.

One story says that an old Eskimo woman lived with her little son, and as they were very poor they had to depend on small gifts of blubber and seal’s meat. On one occasion the boy was so hungry that he kept crying out for food, and in spite of his mother’s threat to call Kalopaling, the noise continued until the woman became so angry that she actually called the monster, who walked away with the shrieking child hidden in his enormous hood. Later on, food became plentiful, and the woman told Eskimo fishermen how sorry she was that her little son had been taken away, and before long a brave hunter and his wife promised to help her to secure the child.

Kalopaling used to allow the boy to play near the edge of a large crack in the ice, but always had a rope of seaweed around him, so that he could be pulled into the water when any one was approaching. The hunter and his wife made several unsuccessful attempts to rescue the boy, but at last their patience was rewarded, for coming out quickly from their hiding-place behind a block of snow, they cut the rope of seaweed, and carried the lad to his mother’s hut, where he grew up to become a great hunter.

Ages ago there lived on the shore of Davis Strait a young orphan boy named “Kaud,” who, on account of his loneliness, was so ill-treated that he was not allowed to sleep in the hut, but had to cuddle up to the sledge dogs which lay outside. His food consisted of the toughest pieces of walrus hide, which he was obliged to eat without a knife, until a little Eskimo girl took pity on him and made him a present of a knife, which he concealed in the hood of his jacket. So badly treated was young Kaud that he remained very small, and even young children took advantage of his weakness and ill-treated him when at play. When the villagers gathered in the house used for singing, Kaud would lie in the passage listening to the music, and wishing he could take part in the enjoyment. Sometimes a sturdy man would look out, and espying young Kaud, would take him by the ear and lift him into the room, where some heavy task would be found for him.

The man in the moon had for some time been watching the miseries of this Eskimo orphan, and at last decided to come to earth and help him. For a time the small boy was too frightened to leave the hut where he was hiding, but soon ventured forth, and to his surprise the man from the moon told him to move some very large stones, which seemed too heavy even for a strong man. Of course Kaud could not move the stones although he tried very hard, when the man from the moon began to flick him with a whip and shout, “Now, do you feel stronger?” “Yes, I feel stronger,” said poor Kaud; but as the stone was still in the same position the man from the moon used his whip a little more freely. At last the stone moved just a little, and the small boy, encouraged by success, exerted his strength, which was every moment increasing, and to the delight of his taskmaster he was soon able, not only to move the stone, but actually to lift it a great height from the ground.

“Very good,” said the man from the moon. “To-morrow I will send three bears, then you may show your full strength.” So saying, he got astride a cloud and sailed away towards the full moon, whose silver light was glistening on the frozen snow. Next morning three large bears made their appearance in the village, much to the dismay of all the men, for not even the oldest hunter had seen such large, fierce, white, shaggy bears.

The men, who crowded timidly into their huts, were astounded when they saw the boy whom they had despised and ill-treated making his way quickly towards the ferocious animals. “The bears will soon finish him,” said the men; but this was not to be, for Kaud seized one animal by its hind legs and, exerting all his strength, swung it round so that its head crashed against a sharp piece of ice, and the animal lay quite still. A second bear was treated in the same way, and at this point Kaud determined to have his revenge on those who had ill-treated him when he was little and weak. So he secured the mouth of the third bear with a thong made of reindeer’s hide, then lifting the huge animal, he carried it into the village as easily as he would previously have lifted a young puppy. He unmuzzled the bear, and pushed it among his enemies, who fled across the snow with the great animal in pursuit. Then there came from a hiding-place the little girl who had presented a knife to Kaud when he was young and weak, and after a few days spent on a very pleasant honeymoon among the hills of snow, Kaud and his bride settled in a snow hut near the sea, and it is said that the boy who had been so weak became a hunter whom every one feared and admired.

The Eskimo are particularly fond of stories describing some poor ill-treated boy who lived to become strong and famous, so in the story of Kiviung we have no exception to the general rule.

This poor boy was kept by a grandmother who had no one to go out hunting, and no articles to offer in exchange for skins of the seal and reindeer, so it came to pass that both of them had to be content with clothes made from the skins of birds, instead of the double fur suit which Eskimo people usually wear. Playmates who were better clad mocked young Kiviung, and some went so far as to tear his birdskin coat, a cruel act which made him run home to his grandmother, crying for protection.

Now it so happened that the grandmother was a very clever witch, but no one knew of this, for the old lady had been too kind to harm any of the villagers until her anger was aroused by the unkind treatment of her grandson, who had many times been chased home by big strong men who called out insulting remarks concerning the birdskin suit.

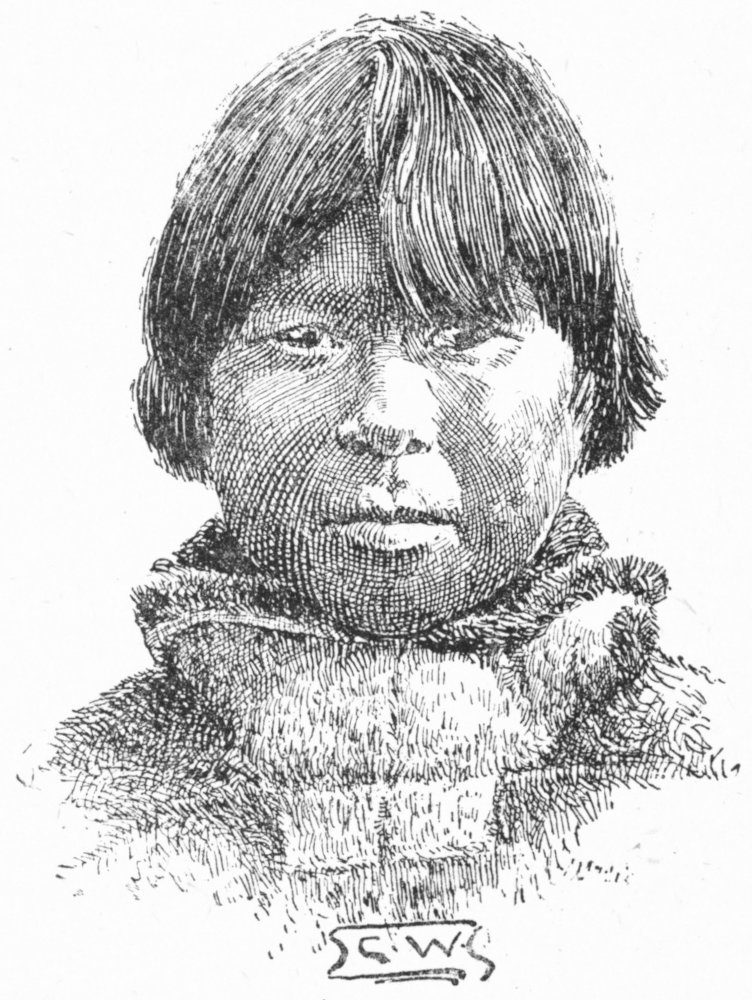

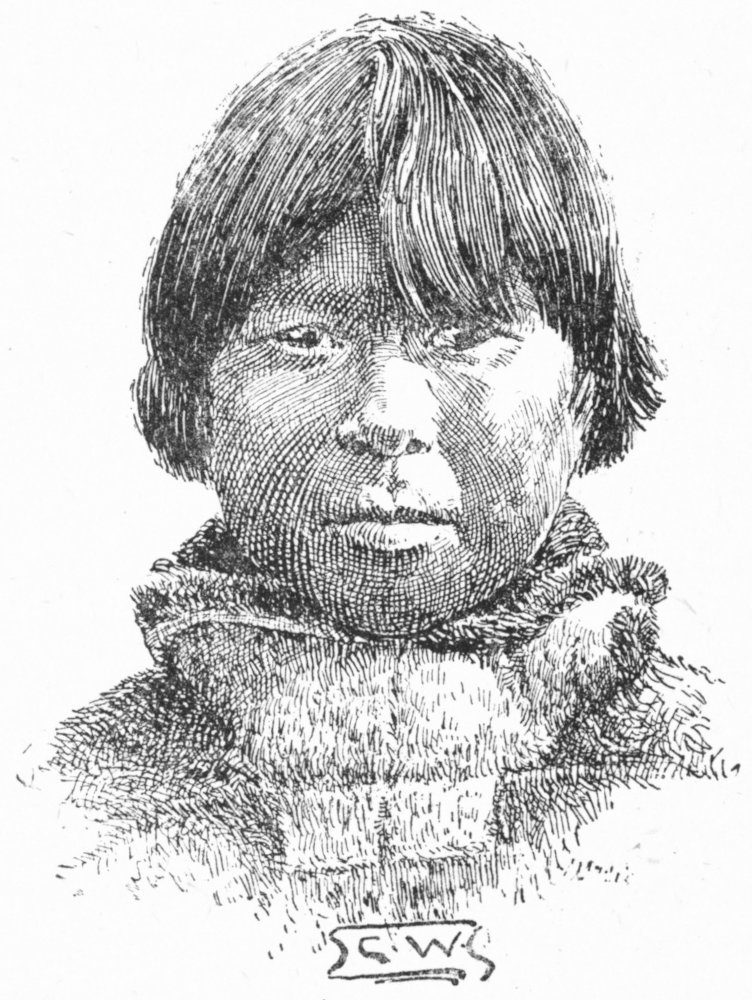

AN ESKIMO BOY.

At last the old woman swore to have revenge, and in order to do this she commanded her boy to step into a puddle which had formed in their miserable dwelling. No sooner had he obeyed than he was transformed into a healthy young seal. His coat was so beautiful and glossy that it attracted the attention of all the villagers, who watched him basking on a piece of ice near the shore. Then the kayaks were launched, and each Eskimo began to paddle furiously in the direction of the young seal, which could see the cruel-looking harpoons always carried by the hunter. Nearer and nearer they came, then the baby seal slipped gently from the ice and disappeared beneath the surface of the cold green sea. Presently he came up to breathe, and at the same time noticed with pleasure that all the kayaks were being swiftly paddled in his direction. So diving once more, he headed for a most dangerous piece of water, where heavy green seas were breaking, and huge pieces of ice were floating about, dashing together with a crunching noise. Excited by the chase, these Eskimo hunters had no thought of danger, and so little Kiviung, in the form of a seal, led them into the perilous position from which no one escaped. Once among the billows and blocks of ice, these frail kayaks, made of skin stretched over a frame of whalebone, were tossed about and dashed against the ice until not one of them remained on the surface, and the hunters, after a few feeble struggles in the ice-cold water, sank down and down into the regions inhabited by fierce Kalopaling.

The agile little seal used his tail and strong flappers to good advantage, and presently landed safely at a point where the old witch, his grandmother, was waiting to restore him to human form. This severe lesson had a good effect on the remaining inhabitants of the Eskimo encampment, and never again were they inclined to be cruel and unkind to those who were weaker and poorer than themselves.