CHAPTER III

MASAI STORIES AND BELIEFS

At all periods of the world’s history human beings have been fond of stories concerning animals, and the Masai are no exception to the general rule. Here is a story of the hare and the elephants, one of a number collected by Mr. Hollis, who resided among the Masai for several years:

“A hare, that lived near a river, one day saw some elephants going to the kraals of their father-in-law. He said to the biggest one, who was carrying a bag of honey: ‘Father, ferry me across, for I am a poor person.’ The elephant told him to get on his back, and when he had climbed up they started.

“While they were crossing the river the hare ate the honey, and as he was eating it he let some of the juice fall on the elephant’s back. On being asked what he was dropping, he replied that he was weeping, and that it was the tears of a poor child that were falling. When they reached the opposite bank the hare asked the elephants to give him some stones to throw at the birds. He was given some stones, which he put into the honey bag. He then asked to be set down, and as soon as he was on the ground again he told the elephants to be off.

“They continued their journey until they reached the kraal of the big one’s father-in-law, where they opened the honey bag. When they found that stones had been substituted for honey they jumped up and returned to search for the hare, whom they found feeding. As they approached, however, the hare saw them and entered a hole. The biggest elephant thrust his trunk into the hole and seized him by the leg, whereupon the hare cried out: ‘I think you have caught hold of a root!’ On hearing this the elephant let go and seized a root. The hare then cried out: ‘You have broken me! You have broken me!’ which made the elephant pull all the harder, until at length he became tired.

“While the elephant was pulling at the root the hare slipped out of the hole and ran away. As he ran he met some baboons, and called out to them to help him. They inquired why he was running so fast, and he replied that he was being chased by a great big person. The baboons told him to go and sit down, and promised not to give him up. Presently the elephant arrived, and asked if the hare had passed that way. The baboons inquired whether he would give them anything if they pointed out the hare’s hiding-place. The elephant said he would give them whatever they asked for, and when they said they wanted a cup full of his blood, he consented to give it them, after satisfying himself that the cup was small. The baboons then shot an arrow into his neck and the blood gushed forth. After the elephant had lost a considerable quantity of blood he inquired if the cup was not full. But the baboons had made a hole in the bottom of the cup, which was still half empty. The elephant suddenly felt very tired, lay down and died, upon which the hare came from his hiding-place to continue his journey.”

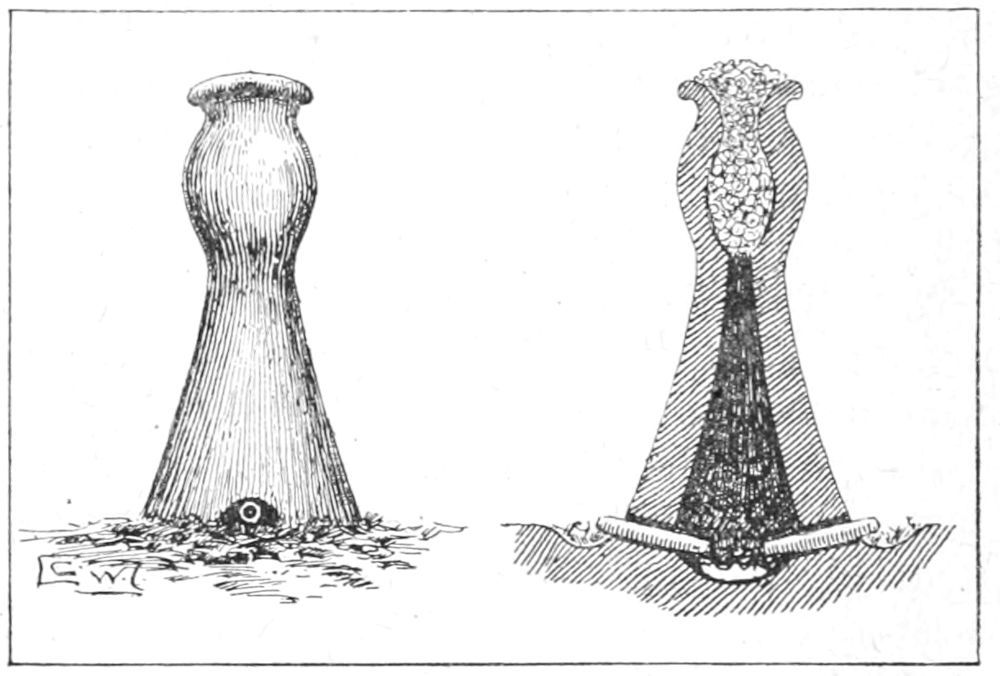

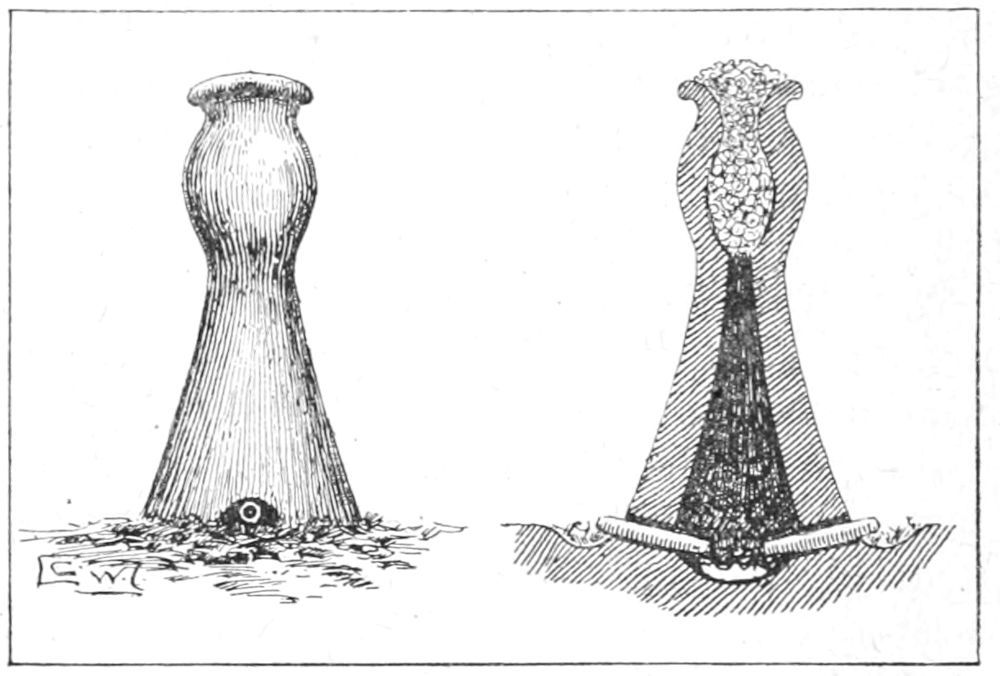

PRIMITIVE SMELTING FURNACE, AND SECTION OF SAME, SHOWING BLAST-PIPES, FUEL, AND ORE.

Some stories are concerned with the work of evil spirits, and, of course, tales connected with warriors’ exploits are very popular. Before setting out on a raiding expedition a band of warriors consulted a wise man of the tribe, known as the “medicine man,” who said that the expedition would be unsuccessful if any warrior killed a monkey while on the march. A coward who heard this made up his mind that he would kill a monkey, then perhaps the attacking band would run instead of fighting. On the way to the scene of the combat this coward observed some monkeys, so, pretending to stay behind in order to fasten his sandal, he killed one of the animals, then quickly rejoined his comrades, who by this time were near the village they intended to attack. Outside a kraal an old man was seated, and at once a club was thrown at him by one of the Masai warriors. This did not appear to harm him in the slightest, for he only complained of the flies, in fact he seemed to be proof against all the clubs and spears launched against him. Presently he rose and, single-handed, put to flight the whole band of attackers, who then knew that one of their number had been false. Steps were taken to find out who had disobeyed the command of the old witch doctor, and suspicion fell on the warrior who stayed behind to fasten his sandal. He became very much afraid when questioned by his comrades, and on confessing that he had spoiled the expedition by killing a monkey, he was speared to death on the spot.

A story such as this shows the Masai to be very superstitious people who believe in omens and ill-luck. They have a word “ngai,” which means anything strange that they do not understand, and this is given to railways, telegraph lines, and thunderstorms, all of which are very terrifying and mysterious. The people believe in four gods, each distinguished by a colour. The black god and white god are good, the red god is bad, and the blue god neither good nor bad. It is believed that all these gods lived in the sky, but only the Black God came to earth as a man, and from him are descended the Masai people, who still live near the lofty Mount Kenia, the supposed dwelling-place of the Black God.

Compared with other peoples of Africa the Masai are not very superstitious, though no doubt we should think their beliefs very strange and fanciful. No poor man is thought to have a soul that can live after his body is dead, but the spirit of a rich man is believed to enter a snake, which then visits the tribe and acts in a peculiar way to warn them of danger. When rain is badly needed, all women and children gather bunches of grass, which are held in the hand, while they stand in a circle and pray to the Black God to send water for their pastures and cattle.

A thief is punished by a heavy fine of cattle or weapons, which have to be paid over to the man from whom goods have been stolen. Sometimes a thief is severely beaten; this is usually done when he has been previously detected in crime, while if a third theft is committed by the same person his hands are burned with a hot stick.

A murderer has to pay all his flocks and herds to the relatives of his victim; this is known as paying “blood-money,” a practice which was common in our own country in Saxon times. Some laws are very amusing: for instance, if two men fight, the injured person may claim eight cows for loss of a limb, one cow for a tooth, two cows for the loss of two or three teeth; so quarrelling may prove a very expensive pastime.

What then is the end of this life of fighting and cattle rearing? In the case of a chief, respectful burial and a belief that the soul of a great man will visit the relatives in the form of a snake. But for a poor man there is no funeral; the body is carried to the bush, where it is soon devoured by hyenas.