CHAPTER II

THE FIGHTING MASAI

In the year 1895 British East Africa, formerly governed under a Royal Charter held by the Imperial British East Africa Company, came directly under the management of the British Foreign Office. Thanks to the assistance of the Masai, hostile tribes, such as the Wakamba, were completely subdued; and on our side it may be said that protection was given to the Masai against their treacherous and warlike neighbours the Akikuyu.

Perhaps the term “warlike” should no longer be applied to Masai tribesmen, for of late years they have been extremely peaceful. Misfortunes, such as loss of cattle by a disease called “rinderpest,” and outbreaks of small-pox, have made this very independent tribe rely on the British Government for advice and protection.

There are certain points in which the Masai resemble Zulu tribes; for instance, their fighting men must not marry, and there is a royal family from which a chief is always selected. Some of the marriage customs are very similar, and among both Zulus and Masai there are like methods of painting warriors’ shields in order to distinguish companies and larger units. Against all these points of comparison there is one important fact, namely, difference in language, which very strongly suggests that the Zulus and Masai are not related.

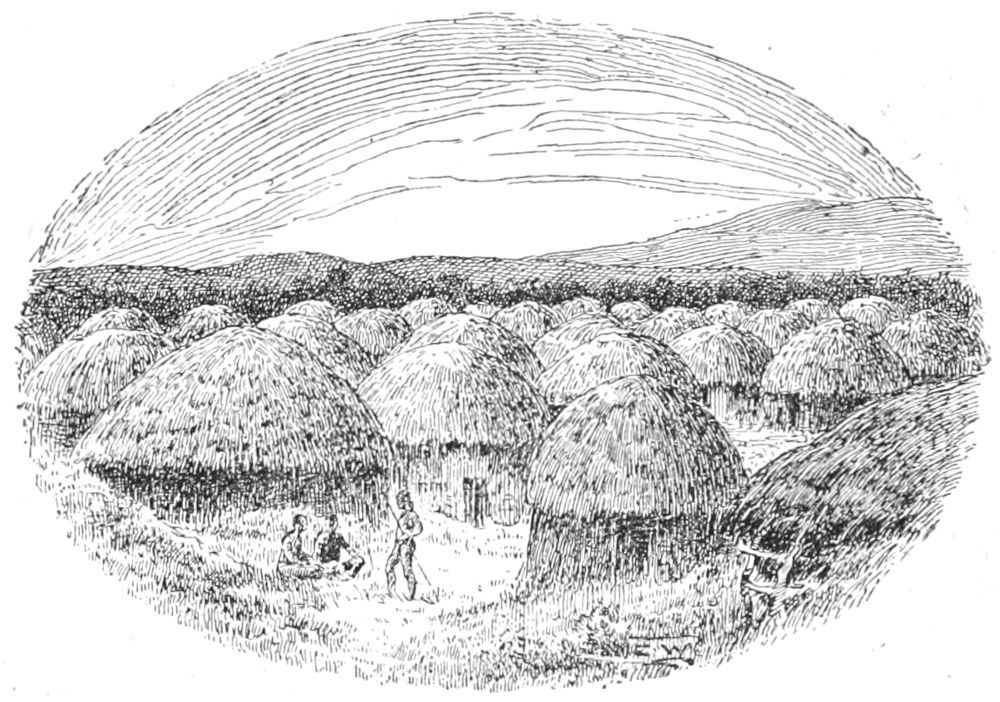

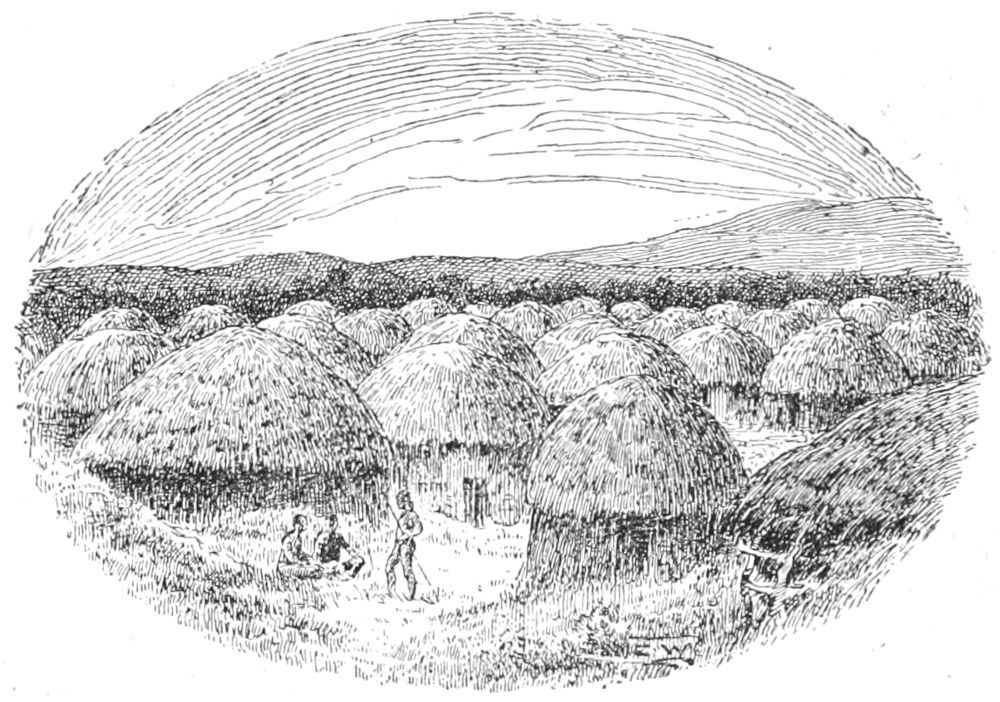

A MASAI VILLAGE.

Though slaves are unknown amongst the Masai, there are a servile people named the Dorobo who have to obey the commands of their masters; but, on the other hand, they receive wages, and must not be bought or sold. Very probably these people who serve the Masai were at one time captured and enslaved; now they do not possess any cattle, and as a rule the hardest work falls to their lot. An East African official, Mr. Hinde, says of these Dorobo: “They do not build kraals after the manner of the Masai, but inhabit clusters of badly built huts hidden in the bush. In war they are not allowed to accompany the Masai, or to carry shields and spears. Their weapons consist of a bow, poisoned arrows, and a heavy wooden-handled spear, into one end of which a massive arrow-head is placed. This arrow-head is thickly smeared with poison. In attacking large game, such as the elephant, hippopotamus, or rhinoceros, they drive the arrow-head into the animal, whereupon the heavy shaft drops off and is recovered. A new tip is fitted, and the native, following the wounded animal, shoots these poisoned arrows until the creature drops from exhaustion.”

A Masai chief is a person of the greatest importance; and in former days, when the tribe was about to undertake a great raid on some neighbouring people, the king would throw himself into a trance, in which he had visions of the proper way of conducting an attack or defence. On other occasions his power of second sight caused him to foretell possible calamities, and before waking he suggested some means of avoiding them.

Very probably the king practised a good deal of deception, for it is well known that he had a secret service system which informed him of all that was taking place in his own and adjacent tribes. A son of the royal house will always preserve his father’s skull, which, if kept near, is supposed to bring good luck, and assist in ruling the country. The bodies of ordinary people are just allowed to remain in the bush, and a funeral, burial, and mound of stones are given only to members of the royal household.

The Masai are a very bright, intelligent, and truthful people; very rarely will a full-grown man commit a theft or tell a lie. Unlike many African tribes, these people have no musical instruments, and their few war songs and verses, sung while herding cattle, are very simple. Generally speaking, African natives are musical, and flutes, drums, also stringed instruments are very ingeniously made.

Of the personal appearance of the Masai, Mr. Hinde has said: “The adult male Masai may be described as tall and spare, with sloping shoulders and small hands and feet. The sloping shoulders are probably due to a complete absence of manual labour, and to the constant carrying of a shield or spear in either hand, each weapon weighing eight or nine pounds. Compared with his height an average Masai could not be considered broad-chested. A habit of stooping, and leaning the head forward when running, gives a slovenly appearance, only slightly detracted from by an abnormally long stride. They are extraordinarily fleet of foot, and can run without tiring for incredible distances. Their usual pace is a long loping trot.”

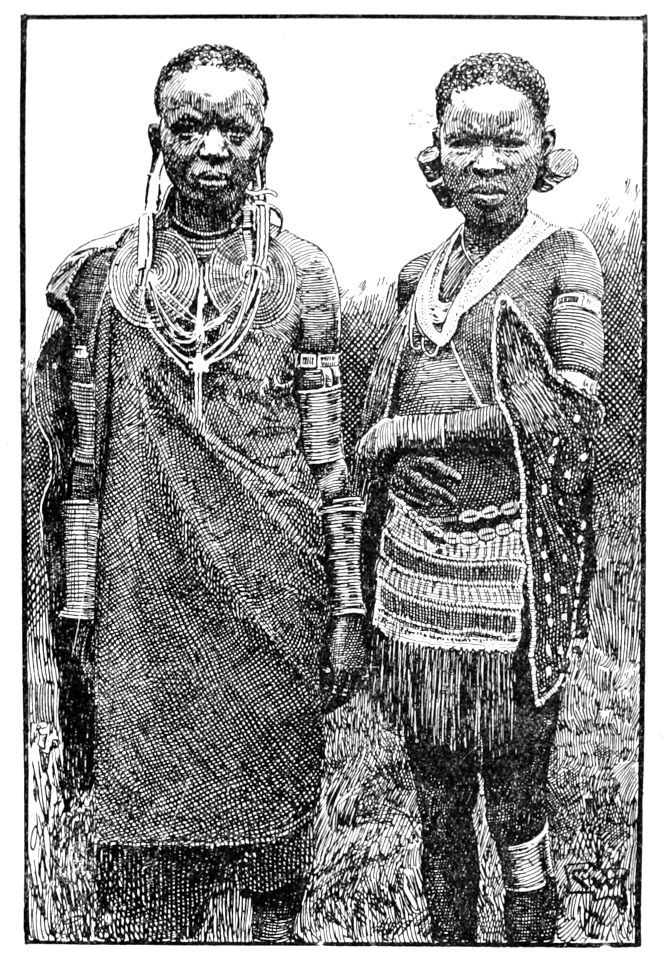

One very strange custom, looked upon as a means of ornamenting the head, is boring the ear lobe and inserting an object of large size. From time to time a larger object is put into the hole until the ear becomes enormously distended; some natives have been seen with ear ornaments consisting of one-pound jam tins inserted in holes made in the ear lobes.

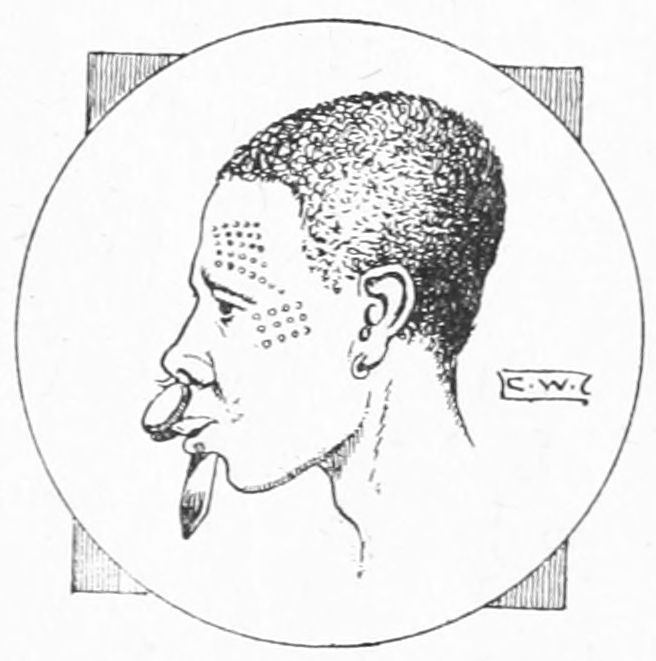

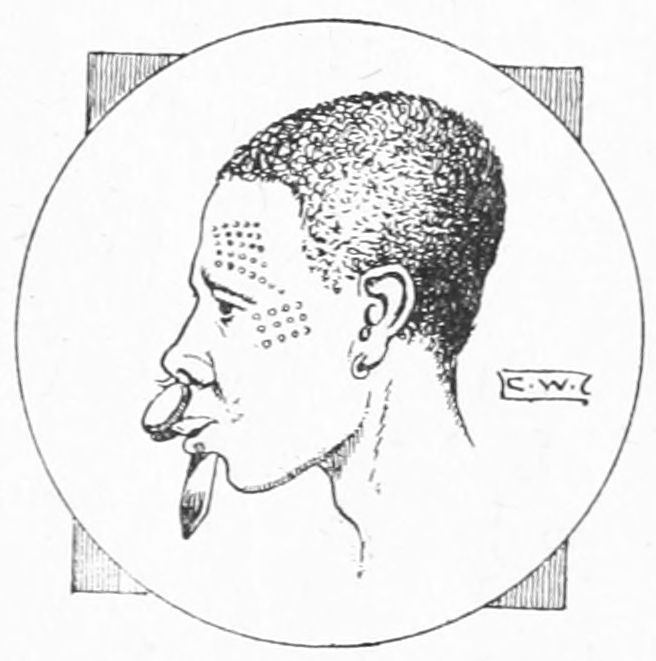

Some women prefer lip ornaments of great size, which must be in the way at meal-times. The method of introducing these studs is similar to that employed for fitting large ear ornaments. A small hole is filled with a thin plug of wood, the size of which is gradually increased. As a rule a lip stud projects into the wearer’s mouth, so that at least two teeth have to be extracted.

Another favourite form of ornament consists of burning the skin with acid juices derived from plants. Small circular scars arranged in patterns are made, and in the Shilluk tribe of the Nile Valley men have four rows of such scars right across their foreheads. Women of the tribe have two or three rows. Sometimes these scars are made merely for ornament, or the marks may serve to show the tribe to which a person belongs.

MITTU WOMAN, SHOWING LIP ORNAMENT AND TATTOOING BY SCARS (CICATRISATION).

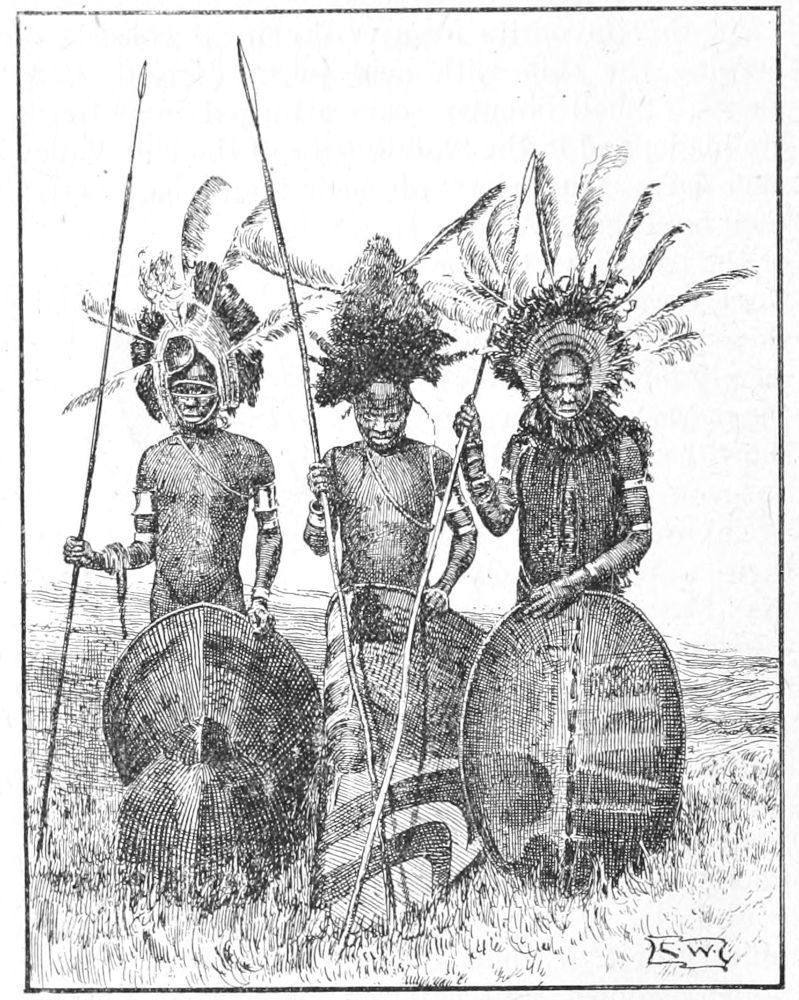

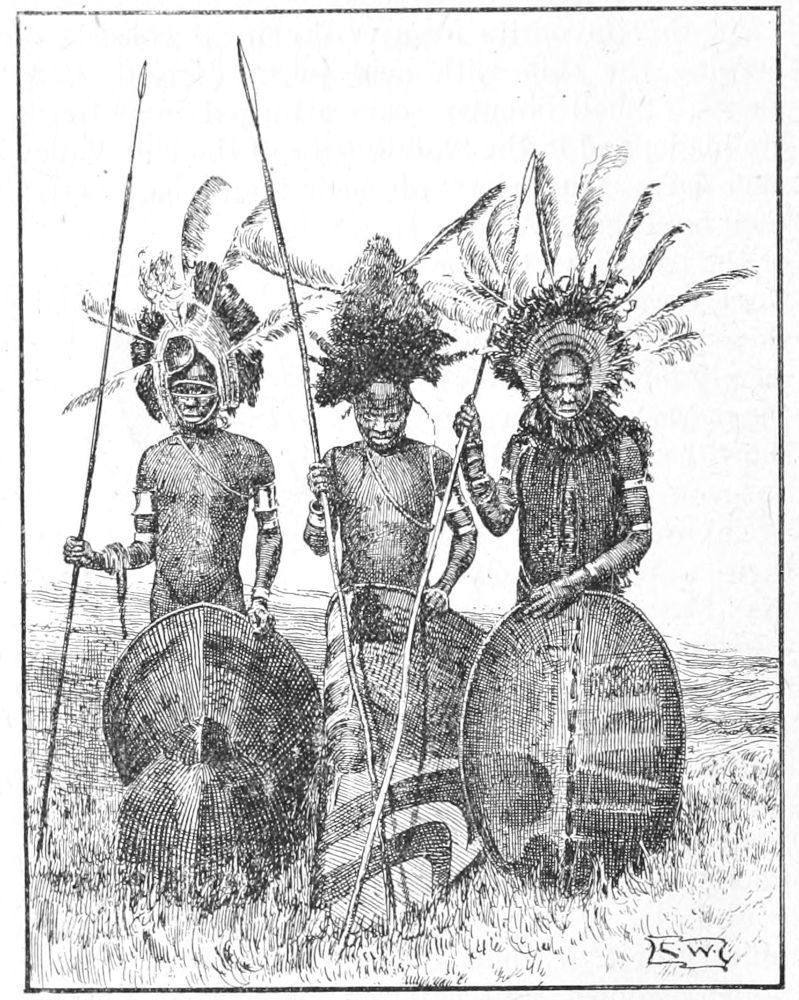

Kavirondo men and their near neighbours, the Masai, are great warriors. In the latter tribe boys serve a long arduous military training, and it is a proud day when they are allowed to assume the full war-time outfit. The headdress helps to conceal people who are crouching among long grass. The armlets are merely ornamental, but the patterns on shields denote the military unit to which the warriors belong.

WARRIORS OF THE KAVIRONDO TRIBE IN FEATHER HEAD-DRESSES.

Men, women, and children have clean shaven heads, and it is quite an exception for a man to show any sign of beard or moustache. Although washing the body and clothing is unpopular, the Masai have great pride in their teeth, of which most perfect care is taken, and whiteness and polish are obtained by frequent use of a small stick. Knocking out the upper central teeth is a strange custom, said by the people to have been invented at a time when there were many cases of lock-jaw, and the patients had to be fed through the hole made by extracting these teeth. In some instances small pieces of iron are worn, not as ornaments, but as a protection against, or cure for disease.

All over the Sudan this wearing of charms is common, and amongst the Mohammedan people the amulet is made by wrapping a verse from the Koran in a roll of leather, generally worn round the neck or on the arm.

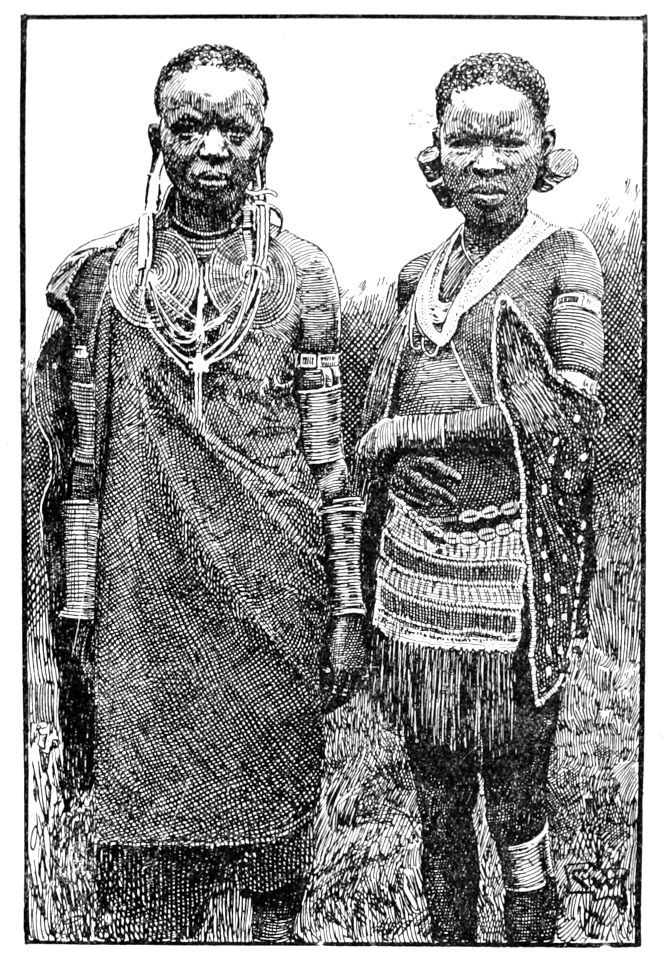

The ornaments worn by Masai women are most noticeable, and the traveller is surprised that the wearers can move arms and legs sufficiently well to perform their work. Iron wire is wound round the arms from wrist to elbow and from elbow to shoulder; the legs also are encased in iron wire from ankle to knee-joint. Metal collars, which look most uncomfortable, are still made and worn by women and boys, who seem willing to tolerate any amount of discomfort rather than go without these ornaments.

Amongst the Masai there is a belief that ill luck will follow if a man is called by his own name, and to avoid this he must always be addressed by his father’s name. When asked for his name, a man will always give that of his father; his own name must be inquired from some third person. As among ourselves, names are handed down from father to son, and among the Masai the father’s name is almost invariably given to his favourite son. Superstitions with regard to names are carried still further. Suppose several people in the tribe have the same name, this must be changed immediately on the death of one of them, for it would be considered very unlucky to retain the name of some one who had just died.

LUMBWA WOMAN AND GIRL, SHOWING DRESS AND ORNAMENTS OF WIRE, ETC.

Boys of the Masai tribe have a very hard, unhappy life, for not only are they made to do all the hard work of carrying, milking and driving cattle, but in addition every one treats them harshly, and a boy may not even speak to one of the warriors. Presently the conditions improve, and elder boys go out shooting birds with bows and arrows, in order to get feathers for making mantles worn by warriors. At last the youth reaches an age at which he is allowed to live in the warriors’ camp, where there is strict training, and no excess in eating or drinking is allowed; smoking is quite forbidden. As the military training advances, the boy becomes the proud possessor of a painted shield, a spear, a sword, and a knobkerry or club. These weapons are kept in perfect condition, the spear-heads being brightly polished with a hard stone. Warriors are the only people allowed to grow their hair, and each fighting man possesses a “pig-tail,” of which he is very proud.

Before making an attack, Masai warriors chew bark from the mimosa tree. This acts in such a way as to make them nearly mad with ferocity, and when all are very wild and excited the enemy is engaged. Enemies face one another in long lines, and instead of a general attack being launched single pairs are engaged in combats which are a fight to the death. In case of success the victors will seize the best cattle, which are driven off to the pastures of the conquerors. It is said that the Masai never attack by night or by stealth; there is always a preliminary warning and invitation to “come out and fight to the death.”

Although young boys have such a hard time in order to make them fit to be trained as fighters, girls of the tribe are very kindly treated. Young maidens spend a great deal of time in singing, dancing, and ornamenting themselves; as a rule, they do not even cook their own food. Old women have all the hard menial work to perform, and very hard is their lot in building huts, carrying loads when the tribe moves, collecting firewood, and keeping night watches. Speaking of old women in the Masai tribe, Mr. Hinde says: “As long as she can crawl about she continues her labours, and death is the only release she can hope for.” As a rule, a girl becomes the wife of a man who can afford to pay goats and cattle for her; but the Masai parents consider their daughter’s wishes, and she is not obliged to become the wife of a man she does not like.

The life of Masai people depends almost entirely on herds of goats and cattle, which are driven from pasture to pasture. Reptiles, birds, insects, and fish are never eaten, grain only at times when meat is scarce, while a favourite food is blood, drawn from the neck of a cow by making a small puncture with an arrow, in such a way as to avoid injuring the animal severely. Herds of cattle, though very docile and easily managed by small children, are extremely fierce, and well able to protect themselves against attacks made by hyenas or a leopard.

Though so bold in warfare the Masai are not a race of hunters, and big game such as lions, leopards, or the rhinoceros are attacked only when the skin is required, or the animal has become a menace to the herds of cattle.

Among the industries, smelting of iron in clay furnaces is very important, as it provides spear-heads and ornaments. These are not moulded by allowing molten metal to run into vessels, but the ore, heated in a charcoal fire, is beaten into shape while resting on a block of hard wood or stone.

Clay taken from river beds serves as material for making earthenware vessels, which are baked hard in a fire after being moulded by hand into the shape required. Other vessels are made from gourds, while as a pastime the carving of wooden pipes and ornamenting the bowls is very common.

Hut building with such materials as hides, mud, and sticks, likewise the construction of a stone and bush enclosure round the village, take a great deal of time; so also does a complete removal to fresh pastures. Hence in one way or another the time of these people is fully occupied, and it is a great mistake to suppose that all black people are lazy and indolent.

There must, of course, be time for leisure, which is sometimes spent in telling the stories given in the next chapter.