CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

A few years ago two dwarfs or Pygmies from the trackless forests of Uganda were bold enough to allow themselves to be brought to London, where they were exhibited and photographed. Unfortunately these little people had no one who could interpret their language, or what a wonderful story they might have told concerning life in an equatorial forest, where the foliage is in places so dense as to shut out the powerful glare of a tropical sun.

Many years ago these dwarfs were known to the highly civilised inhabitants of Ancient Egypt, and as early as 3000 B.C. the leaders of expeditions into the Sudan were charged by the Pharaohs of Egypt to return with gold dust, ivory, ornamental woods, and leopard skins; but above all these forms of wealth King Pepy II. desired a Pygmy “alive and well.”

These tiny folk, whose height is rarely more than four feet nine inches, live the simple life of hunters, almost devoid of clothing, possessing neither basket-work nor pottery, and armed only with flint-tipped spears and small poisoned arrows. Of agriculture they have no knowledge, for their time is wholly occupied by the dangerous pursuit of large and small game.

What a sharp contrast to these pygmies are the giant tribes of the Upper Nile, where the Shilluks are usually six feet four inches in height, and a man of only six feet would be regarded as short!

Many centuries ago, but at what time in the world’s history it is impossible to say, a tall, dark-skinned people named Hamites entered Africa from the direction of Arabia, and so fierce were these invaders that they were able to push before them the negroes, who retreated south and west. These fighting Hamites are now represented by the Somali, Danakil, and Galla who inhabit the “Horn of Africa,” where they subsist chiefly by cattle rearing; that is to say, they are a pastoral people, who move from one well and piece of grass land to another, driving before them large herds of sheep, goats, camels, and perhaps a few horses.

Of course the Hamites mixed with the true negroes to some extent, so forming the great Bantu race which inhabits most of our Uganda Protectorate. The dreaded Masai of British East Africa are probably a cross between the Negro and the Galla. Arab tribes have for centuries wandered through East Africa as traders and slave raiders, so we have to consider a very mixed people.

What a variety of country, too, in the British territories called the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, Uganda, and British East Africa!

WOMAN CRUSHING GRAIN ON A CONCAVE STONE WITH AN OVAL STONE ROLLER.

Everywhere along the banks of the Nile there is fertile country, but in the Sudan territories of Kordofan, Sennar, and other provinces, are seemingly boundless tracts of desert, broken here and there by rocky hills or “gebels,” which perhaps attain a height of three or four hundred feet. In such places large dog-faced baboons abound, hyenas shelter in the caves, and near to the wells, usually found among the rocks, are native encampments, where dwell Arabs, Taishi, and Baggara people, who fought so determinedly against the English in 1885. Now, however, they are quite friendly, and the traveller may be invited into the “zereba,” an enclosure containing a number of circular huts with pointed roofs, and here refreshment of coffee and milk is provided. Thin miserable dogs bark defiance at the stranger, who keeps them at bay with his whip of rhinoceros hide. Little naked children play about in much the same way as white youngsters amuse themselves, but they are more delighted than their white cousins would be by the gift of a wire bracelet or a string of beads. Outside the huts kneeling women crush the grain—“dhurra”—on slabs of stone; and what an enormous pile of this crushed grain a Sudanese will eat! Seldom does he enjoy the luxury of meat. A whitish, muddy-looking liquid may be offered to the visitor; this he had better avoid, for it is native beer, made by allowing soaked “dhurra” to stand in the sunshine for several days. If the village population has reached two or three thousand, there are sure to be a few Arab merchants who have brought their calico, dried dates, and other wares all the way from Khartoum or Wad Medani. There they sit by the goods, which are laid out on the ground, possibly reading a chapter from the “Koran” or Mohammedan Bible, while a small group of natives gather round and decide how to spend the money which they have only recently learned to use, instead of bartering, that is, changing one article for another.

In many parts of the Sudan natives are employed on irrigation works or railways, where the workmen are paid with Egyptian coins. Even now a native prefers to have a lot of little coins, and would at any time receive several small coins rather than one silver piece.

Uganda and British East Africa can show enormous tracts of park land, where European enterprise is engaged in cattle rearing, and native tribes such as the Masai rely on their flocks and herds for a living. In no part of the world, not even in the Amazon valley, are the forests more dense than those of Uganda, where the traveller finds Bantu tribes existing much as they have done for thousands of years.

When reading of railways connecting Port Sudan, on the Red Sea, with Khartoum, or of a line from Nairobi in British East Africa to Port Florence on Victoria Nyanza thence to the great port of Mombasa, one is apt to think that these East African Protectorates must be very advanced in civilisation, but this is not the case.

In a journey from Khartoum southward into the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, or from Port Sudan to Khartoum, the traveller is very much impressed with the luxury of the train in which he travels through the wildest scenery, comprising dense prickly bush, dreary wastes of sand, and rocky hills. Native children run away screaming on the approach of a train. In the journey from Khartoum to the Red Sea one encounters the Hadendoa people, who make themselves appear very tall and wild by allowing their hair to grow perpendicularly in a huge bush on the top of the head. In Uganda and British East Africa the traveller may have the experience of having his train charged by a buffalo, rhinoceros, or elephant, who mistakes it for some powerful rival, come to settle in the tropical forest which he has enjoyed undisturbed for so many years.

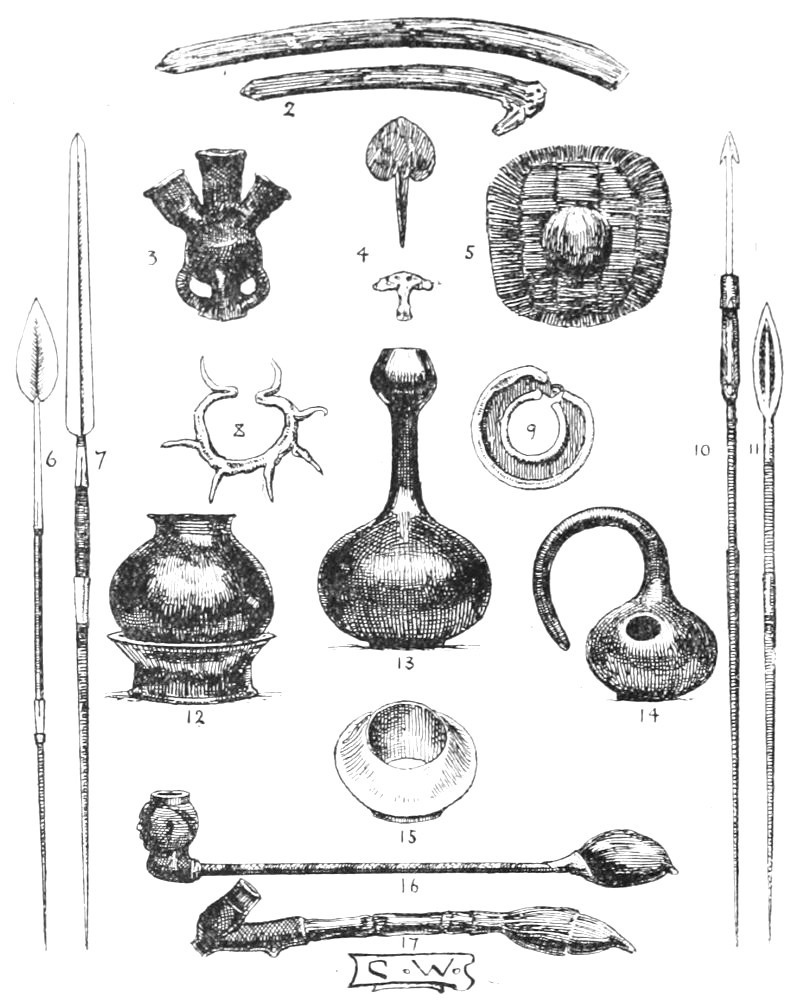

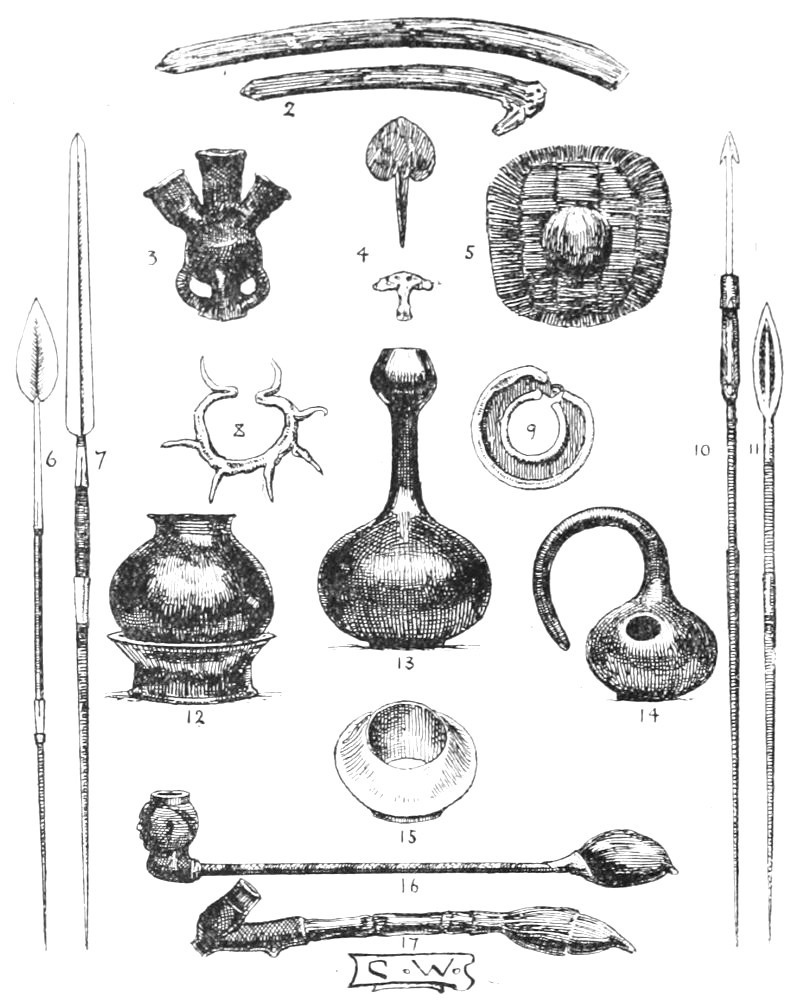

1, 2. Throwing-clubs from the Nile Valley.

3. Pot from which victims for sacrifice were made to drink a magic draught to “kill” their souls, and thus prevent their “ghosts” from returning to punish their murderers.

4. Conventional hoe-blades used as money (Upper Nile).

5. Small shield of the Hamites, west of Victoria Nyanza (Uganda).

6, 7. Old and modern Masai spears.

8, 9. Fighting bracelets (Upper Nile).

10. A Dorobo elephant harpoon (East Africa Protectorate). The arrow shaft fits loosely into the haft, which falls away when the animal is struck.

11. Spear of the Hamitic tribes.

12, 13, 14. Pottery vases blackened with plumbago. One is in the form of a gourd (Baganda, Uganda).

15. Ivory armlet, Shilluk tribe (Upper Nile).

16, 17. Tobacco pipes (Upper Nile).

The savage peoples of East Africa are in many ways much more advanced in civilisation than the native tribes of Australia. The latter are simple hunters, possessing no clothing, no dwellings, no knowledge of metals, pottery making, or basket weaving. On the other hand, native inhabitants of East Africa have left the Stone Age far behind, and almost everywhere a knowledge of iron ore, smelting, and manufacture of spear-heads has been acquired. Ancient stone implements are found in all parts of Africa, but it is generally supposed that knowledge of iron came to the “Dark Continent” at a fairly early date in the history of civilisation.

Everywhere the Negro is an agriculturist, whose women folk cultivate the yam, maize, or banana, whereas a simple hunting tribe in Australia will rely entirely for vegetable foods on what can be collected in the way of wild fruits and berries.

With respect to clothing, weapons, dwellings, pottery, basketry, agriculture, and other forms of manufacture and enterprise, the inhabitants of East Africa are well advanced, while everywhere there is a great system of exchange or barter, which is not always found among more primitive savages, such as the Australian native tribes. Naturally, in so vast an area there are thousands of tribes, hence in this small book there will be space to tell only of a few of the most interesting inhabitants, who had their home in the “Dark Continent” long before the explorers Livingstone, Stanley, Mungo Park, Baker, Burton, Speke, or even early voyagers like Father Lado, Hanno, and the centurions of Nero ventured to penetrate the wilds.